A monthly e-newsletter from UMass Extension, published March to October, for home gardeners.

To read the articles in each section of the newsletter, click on the section headings below to expand the content:

Tips of the Month

March is the Month to.....

-

Inspect trees in the landscape for gypsy moth egg masses. Egg masses are tan and approximately 1½ inches long. If egg masses are safely and easily accessible, they can be scraped into a container of soapy water to reduce the number of caterpillars emerging later. However, for larger infestations, consultation with a professional to plan gypsy moth management is recommended.

-

Dig and transplant small trees and shrubs that need to be moved as soon as soil is workable, since significant new root growth can occur in spring. Furthermore, soils dry quickly as the weather warms and it can be difficult to keep the soil ball around roots together when plants are handled. Store any bareroot tree and shrub seedlings in cool, moist conditions until they can be planted.

-

Pay attention to pruning chores. Cut back damaged tree branches, remove suckers sprouting from the base of fruit trees, and take out about 1/3 of the oldest stems of multi-stemmed shrubs such as forsythia, weigela, beautyberry, and spirea to rejuvenate them. Remember to prune blueberries and raspberries, too, as a lack of pruning is a common cause for poor fruit yield.

-

Cut branches of trees and shrubs for indoor forcing. In addition to the commonly used forsythia and pussy willow, shadbush, redbud, fruit trees, magnolias, and spireas are good candidates for forcing into bloom. The closer plants are to their normal bloom time, the more rapidly they force.

-

Take stock of seed starting materials if this hasn’t been done yet. Seed-starting containers range from commercially available plastic trays and Jiffy pots to recycled household packaging such as clementine crates, egg cartons, yogurt and cottage cheese cups (cut drainage holes in these). There are also plenty of online instructional videos (and even a nifty wooden tool) for creating containers from sheets of newspaper. Regardless of what containers are used, they should be scrupulously clean, and if recycled, sanitized in a solution of 1 part bleach to 9 parts water, to rid them of seedling disease-causing organisms. Growing medium should also be sterile--usually a soilless combination of peat and vermiculite. Other supplies include a light source (cool white fluorescent or LED bulbs), a heat source (germination mat or warm location such as a sunroom or greenhouse), and moisture source (nonchlorinated water and clear plastic lid or bag to maintain high humidity prior to germination).

-

Start seeds of lettuce and cabbage indoors. Seedlings will be ready for transplanting into the garden in 4 to 6 weeks’ time. Experiment with growing various types of cabbage: green for coleslaw, red for salads and braising, and Savoy for cabbage rolls. Look for early, midseason, and late maturing varieties to guarantee an ample supply of this nutrient powerhouse. It’s also a good time to start transplants of cabbage’s cole crop cousins such as broccoli, kale, Chinese cabbage, and bok choi. Once germinated, seedlings of these vegetables like it cool, around 60-65 degrees F.

-

Check houseplants near windows to make sure they are not getting sunburned. Most tropical houseplants prefer low light environments. Now, that sunlight is more intense as the sun rises higher in the sky, these plants should be shaded or moved back from the windows. Additional tasks: begin increasing water and fertilizer to houseplants as they start to show signs of renewed growth; check to see if dividing and repotting is needed.

-

Avoid compacting soil by keeping off lawn areas as much as possible as the soil thaws. Compaction reduces the ability of water to infiltrate soil, which in turn limits the amount of water available to plants. Air supply to plant roots is also reduced in compacted soil, leading to death of those roots and potentially loss of the entire plant.

-

Incorporate organic matter into garden soils in preparation for planting. (Wait a few weeks if soils are poorly drained and still wet.) Bolstering soil organic matter is insurance against drought during the growing season.

Jennifer Kujawski, Horticulturist

Timely Topics

Viburnum Susceptibility to Viburnum Leaf Beetle

Viburnum is a diverse genus with over 150 species, many of which are native to the United States. Generally medium to large shrubs, some species can even be grown as small trees. Ornamental features provide multiple seasons of interest with spring flowers, summer to fall fruits, and many species having good fall color. Flowers can range from snowball like clusters to flat-topped cymes. Berries can be red or blue to black. Most viburnums are adaptable, tough plants. However, the Viburnum leaf beetle has become a problem with many popular species.

Viburnum leaf beetle was identified in Massachusetts in the summer of 2004. Viburnum susceptibility varies by species with the most highly susceptible plants generally devastated in 2-3 years following infestation while the most resistant showing little to no damage. Susceptibility should be taken into account when managing infested plants or when planting new Viburnum in the landscape. In general all species have more feeding damage when plants are in shade. Viburnum leaf beetle prefer species with little or no hair on the foliage.

For more information on Viburnum leaf beetle, go to our fact sheet at https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/viburnum-leaf-beetle

Viburnum species susceptibility

The following chart lists the size and ornamental features of major Viburnum species.

HIGHLY SUSCEPTIBLE: First to be attacked, generally destroyed in the first 2-3 years following infestation.

| Scientific name | Common name | size | fragrant | red to black fruit | blue to black fruit | fall color | native |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

V. dentatum |

arrowwood viburnum |

6-10' x 6-10' |

|

|

X |

variable |

X |

|

V. nudum |

smooth witherod |

5-12' x 5-12' |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

V. opulus |

European cranberrybush viburnum |

8-15' x 10-15' |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

V. opulus var. americana |

American cranberrybush viburnum |

8-12' x 8-12' |

|

X |

|

X |

X |

|

V. propinquum (zone 7-9) |

Chinese viburnum |

6-8' x 6-8' |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

V. rafinesquianum |

downy arrowwood viburnum |

6-10' x 6' |

|

|

X |

X |

X

|

SUSCEPTIBLE: Eventually destroyed; not heavily fed upon until the most susceptible species are destroyed.

| Scientific name | Common name | size | fragrant | red to black fruit | blue to black fruit | fall color | native |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V. acerfolium | mapleleaf viburnum | 4-6' x 4 | X | X | X | ||

| V. lantana | wayfaringtree viburnum | 10-15' x 10-15' | X | ||||

| V. rufidulum | rusty blackhaw viburnum | 10-20' x 10-20' | X | X | SE US | ||

| V. sargentii | sargent viburnum | 12-15' x 12-15' | X | X | |||

| V. wrightii | Wright viburnum | 6-10' x 5-8' | X | X |

MODERATELY SUSCEPTIBLE: Show little or no feeding damage, survive infestation fairly well; varying degrees of susceptibility; usually not destroyed by the beetle.

| Scientific name | Common name | size | fragrant | red to black fruit | blue to black fruit | fall color | native |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V. alnifolium (lantanoides) | hobblebush | 9-12' | X | X | |||

| V. x burkwoodii | burkwood viburnum | 8-10' x 6-7' | X | X | X | ||

| V. x carlcephalum | fragrant viburnum | 6-10' x 6-10' | X | X | X | ||

| V. cassinoides | witherod viburnum | 5-12' x 5-12' | X | X | X | X | |

| V. dilatatum | linden viburnum | 8-10' x 6-8' | X | X | |||

| V. farreri | fragrant viburnum | 8-12' x 8-12' | X | X | X | ||

| V. lentago | nannyberry viburnum | 14-16' x 6-12' | X | X | |||

| V. macrocephalum | Chinese snowball viburnum | 6-10' x 6-10' | |||||

| V. x pragense | Pragense viburnum | 10-12' x 10-12' | X | X | |||

| V. prunifolum | blackhaw viburnum | 12-15' x 6-12' | X | X | X | ||

| V. x rhytidophylloides | lantanaphyllum viburnum | 8-10' x 8-10' | X | X |

MOST RESISTANT: Show little or no feeding damage, survive infestation fairly well.

| Scientific name | Common name | size | fragrant | red to black fruit | blue to black fruit | fall color | native |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V. x bodnantense | Bodnant viburnum | 8-10' x 4-6' | X | X | X | ||

| V. carlesii | Koreanspice viburnum | 4-5' x 4-8' | X | X | variable | ||

| V. davidii (zone 7-9) |

David viburnum | 2-3' x 3-4' | X | ||||

| V. x judii | Judd viburnum | 6-8' x 6-10' | X | X | X | ||

| V. plicatum | Japanese snowball viburnum | 8-15' x 10-18' | X | ||||

| V. plicatum var. tomentosum | doublefile viburnum | 8-15' x 10-18' | X | ||||

| V. rhytidophyllum | leatherleaf viburnum | 6-10' x 6-10' | X | ||||

| V. setigerum | tea viburnum | 8-12' x 5-8' | X | X | |||

| V. sieboldii | siebold viburnum | 15-20' x 10-15' | X | X | X |

Sources:

Viburnum Leaf Beetle Susceptibility to Infestation - http://www.hort.cornell.edu/vlb/suscept.html

Viburnum Leaf Beetle, Univ. of Vermont - https://pss.uvm.edu/ppp/articles/viburnum.html

Viburnum Leaf Beetle, Chicago Botanic Garden - https://www.chicagobotanic.org/plantinfo/faq/viburnum_leaf_beetle

Mandy Bayer, Extension Assistant Professor of Sustainable Landscape Horticulture, University of Massachusetts Amherst

News for Gardeners

An Often Overlooked Weed Management Opportunity

When attempting to manage weed in the lawn and landscape, it is important to take advantage of every opportunity at our disposal. One such opportunity occurs during the establishment and/or renovation process that often occurs in these areas of our properties. At times, it is hard to fight the temptation to adopt the “plant and worry about it later” strategy. This is a path that will likely result in great regret down the road. Weed management at the start of a project can solve many difficult weed problems. The expression “let’s start with a clean slate” should be in the back of your mind as you plan and implement establishment and/or renovation projects in lawn and landscape areas.

Situations where the “fresh state/clean slate” approach may be warranted.

Lawn:

- Weeds cover exceeds 50 percent.

- The presence of difficult-to-control weeds as a result of neglect and/or ineffective management.

- Lack of effective cultural or selective herbicidal options for specific weed species.

- Perennial weeds with asexually vegetative means of reproduction (creeping roots, rhizomes or nutlets).

Landscape:

- The presence of difficult-to-control weeds (including invasive plants) as a result of neglect and/or ineffective management.

- Lack of existing effective cultural or selective herbicidal options for specific weed species.

- Perennial weeds with asexually vegetative means of reproduction (creeping roots, rhizomes or nutlets).

Implementation guidelines

A non-selective, translocated herbicide is the most appropriate when implementing the “fresh state/clean slate” approach. Contact herbicides such as diquat (Reward), pelargonic acid (Scythe) and non-chemical products that contain clove oil, citric acid, acetic acid or orange extract are not suitable, since these contact herbicides will not control perennial weeds, especially those with asexually vegetative means of reproduction.

Lawn: In lawns, the “fresh state/clean slate” strategy focuses primary around the establish of a new turf area when little, if any, of the previous lawn is worth saving.

- Late summer and early fall (August 14 to September 15) is the best time for lawn establishment by seed.

- In preparation for turf establishment, remove existing turf in early to mid-July. If perennial weed regrowth is observed, this process may need to be repeated before seeding. There is no need to be concerned with summer annual weeds (crabgrass, carpetweed, spotted spurge and purslane) that may germinate this late is the season.

- Collect and submit a soil test. Soil test results will indicate if corrective measures regarding soil pH and fertility are necessary.

- Select a seed mixture appropriate for the site based on site conditions and intended lawn area use. This mixture should contain turfgrass species and cultivars of those species that are best adapted to the most limiting site factors (fertility, shade, moisture, traffic/wear and site use).

- Seeding can be done with an overseeder and there is no need to remove the dead surface layer.

- Turf establishment at the end of the growth season while not require a preemergence herbicide application. If annual bluegrass (Poa annua) is a problem, an application of mesotrione (sprayable or on-starter fertilizer formulation) will suppress this fall-germinating winter annual weed.

- Application of a starter fertilizer (water-soluble, quick release) is recommended.

- Irrigation should be applied in the absence of adequate rainfall.

- In the spring following turf establishment, standard weed management practices should resume.

Landscape: In a landscape setting, the “fresh state/clean slate” strategy focuses primarily around the installation of a new landscape, as it may be difficult to rip out an existing landscape with the sole purpose of managing weeds. However, if the landscape ornamentals are overgrown and weeds, including invasive plants, are present, it might be something to consider.

- Determine the most troublesome weed species at the site.

- In most cases, the control of weeds should begin well in advance of the installation of landscapes ornamentals. For spring installations, weed management strategies might need to started the previous growing season. For late season installations, weed management can begin early in the season. While this may be viewed as a lengthy process, it is important to make sure that your weed management objectives are obtained before planting begins.

Randy Prostak, UMass Extension Weed Specialist

Trouble Maker of the Month

Winter Moth and Gypsy Moth Update

Winter moth and gypsy moth are two insects that have defoliated areas of Massachusetts in the recent past. These defoliation events have left many wondering what to expect in 2019.

Winter Moth

Winter moth was identified causing defoliation in Massachusetts in the 1990s and previously had caused defoliation outbreaks in Nova Scotia and British Columbia. Winter moth caterpillars defoliate trees by feeding on emerging buds of deciduous forest and shade trees. Shortly after winter moth was identified, researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, led by Dr. Joseph Elkinton, began a biological control effort using a tachinid fly, Cyzenis albicans. C. albicans is a parasitic fly that develops as a pupa inside the infected winter moth pupa, killing the winter moth in the process. C. albicans was a primary reason for winter moth populations being reduced to below pest levels in both Nova Scotia and British Columbia.

The work of Dr. Elkinton’s team has included the collecting, rearing, and releasing of C. albicans since 2005. In that time, the fly has been released at 44 sites and found to be established at 32 of them. Research at several of the release sites has shown parasitism of winter moth by C. albicans and a corresponding decline of winter moth densities. Winter moth populations in eastern New England are now at an all-time low since 2005 and defoliation from winter moth has largely disappeared. The decline has for the most part has reduced winter moth to a non-pest status similar to what occurred in Nova Scotia as a result of C. albicans and the hard work of Dr. Elkinton’s team. To read more about this, go to https://www.fs.fed.us/foresthealth/technology/pdfs/FHAAST-2018-03_Biology_Control_Winter-Moth.pdf

Gypsy Moth

Gypsy moth was introduced into the US in the late 1860s accidently here in Massachusetts. Gypsy moth had been responsible for periods of wide spread defoliation in Massachusetts, with the largest defoliation occurring in 1981. In 1989, the entomopathogenic fungus Entomophaga maimaiga was found infecting gypsy moth caterpillars. Since that time, the population of gypsy moth has not caused widespread defoliation in Massachusetts until recently. Starting around 2015, increased populations of gypsy moth were being observed as a result of a lack of adequate precipitation during crucial parts of the gypsy moth caterpillar’s development in the spring, reducing infections by E. maimaiga and leading to population increases in gypsy moth. Over the next 2 years, gypsy moth caused widespread defoliation, peaking in 2017 and causing almost 1 million acres of defoliation in Massachusetts.

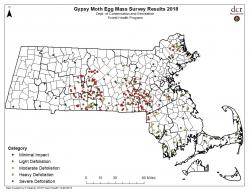

In 2017, early summer rains lead to widespread mortality of the gypsy moths by E. maimaiga. Defoliation was greatly reduced in 2018, resulting in approximately 150,000 acres of defoliation. The MA Department of Conservation and Recreation Forest Health Program conducted their annual egg mass survey, which helps predict the potential for defoliation (Figure 1).

Fig 1. Mass DCR Gypsy Moth Egg Mass Survey Results 2018

Fig 1. Mass DCR Gypsy Moth Egg Mass Survey Results 2018

There seems to still be a concentration of high egg mass numbers in central Massachusetts for 2019. Outside of that area, egg mass numbers appear to be spottier. Look closely at your trees for gypsy moth egg masses to determine whether management may be necessary this year. For more info on managing gypsy moth, go to https://ag.umass.edu/sites/ag.umass.edu/files/pdf%2Cdoc%2Cppt/final_gypsy_moth_fact_sheet_1_column.pdf For info on current conditions, go to https://www.mass.gov/guides/gypsy-moth-in-massachusetts.

Tree Health

The years of defoliation from winter moth, gypsy moth, cynipid gall wasp and the severe drought of 2016 have left a lot our trees, especially oaks, in a state of decline or poor health. These stresses have weakened many of our trees, making them susceptible to further attacks by boring insects like two lined chestnut borer and decay fungi like Armillaria. So, even though winter moth and gypsy moth may not be as a significant threat as in the recent past, don’t forget to keep a close eye on the health of your trees and consider hiring a tree care professional to evaluate tree health and make management suggestions.

Russ Norton, Agriculture & Horticulture Extension Educator, Cape Cod Cooperative Extension

Plant of the Month

Ilex x meserveae, Blue holly or Meserve holly

Blue holly, or Meserve holly, is an evergreen hybrid holly of Ilex aquifolium x Ilex rugosa. They are shrubby in habit and have alternate, leathery, glossy dark green almost blue-green leaves with spiny margins. Plants typically grow to 8-10 feet tall, but occasionally to as much as 15 feet tall. They bloom in May with greenish-white flowers in small clusters which produce showy bright red berries on female plants in fall. The berries often persist until spring. Flowers, although not ornamental, attract bees and the fruits are attractive to birds. Like other hollies, Meserve holly plants are dioecious (separate male and female plants). One male pollinator is needed for every 3 to 5 female plants for berry production. Blue hollies are winter hardy to USDA Zones 5 - 8.

Plants are best sited in locations protected from cold winter winds. Blue holly grow best in slightly acidic, moist, well-drained soils in full sun to part shade. Part afternoon shade is best in hot summers. Blue hollies can be used in mass plantings, hedge or borders, foundations and as specimen plants. Potential problems include interveinal chlorosis (yellowing of leaves in high pH soils), holly leaf miner, spider mites, whitefly and scale, leaf scorch, tar spot, and phytophthora root rot.

Cultivars include:

- ‘Blue Princess' (female) – 15 feet tall, dark blue green foliage and an abundance of red fruit

- ‘Blue Prince' (male) – 8 - 12 feet tall, and very dense, with dark green foliage, very cold hardy.

- ‘Blue Girl' (female) – 8 - 10 feet tall, dark green foliage and bright red fruit.

- ‘Blue Boy' (male) – 10-15 feet tall; dark green leaves.

Geoffrey Njue, UMass Extension Sustainable Landscapes Specialist

Additional Resources

Landscape Message - for detailed timely reports on growing conditions and pest activity

Home Lawn and Garden Resources

Find us on Facebook! www.facebook.com/UMassExtLandscape/

Follow us on Twitter for daily gardening tips and sunrise/sunset times. twitter.com/UMassGardenClip

Diagnostic Services

The UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab provides, for a fee, woody plant and turf disease analysis, woody plant and turf insect identification, turfgrass identification, weed identification, and offers a report of pest management strategies that are research based, economically sound and environmentally appropriate for the situation. Accurate diagnosis for a turf or landscape problem can often eliminate or reduce the need for pesticide use. Sampling procedures, detailed submission instructions and a list of fees.

The UMass Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory at the University of Massachusetts Amherst provides test results and recommendations that lead to the wise and economical use of soils and soil amendments. The Routine Soil Analysis fits the needs of most home gardeners. Sampling procedures plus the different tests offered and a list of fees.

Spread the Word!

Share this newsletter with a friend! New readers can subscribe to our Home Gardener E-Mail List.