A monthly e-newsletter from UMass Extension, published March to October, for home gardeners.

To read the articles in each section of the newsletter, click on the section headings below to expand the content:

Tips of the Month

May is the Month to.....

-

Leave spring blooming bulbs alone! When spring bulbs have stopped blooming, it is tempting to cut back the foliage, but don’t. While leaves are still green, leaves are photosynthesizing and building up sugar reserves in the bulb for next year’s blooms. Although it’s fine to remove the flower stalk, leaves should be left until they turn yellow.

Leave spring blooming bulbs alone! When spring bulbs have stopped blooming, it is tempting to cut back the foliage, but don’t. While leaves are still green, leaves are photosynthesizing and building up sugar reserves in the bulb for next year’s blooms. Although it’s fine to remove the flower stalk, leaves should be left until they turn yellow. -

Get rid of unwelcome or unneeded plants. Start weeding while plants are young and less deeply rooted. Remove invasive species such as oriental bittersweet and Japanese knotweed. It’s also a good idea to remove any plants you no longer want in your landscape (maybe they are overgrown or were damaged in the winter). All of these types of plants use valuable resources such as water and soil nutrients that could be used by other plants in the landscape.

-

Be on the lookout for winter salt injury. Broken branches are usually obvious, but many types of winter injury can go unnoticed into spring, especially on deciduous plants. Flower and leaf buds facing sidewalks or roadways may have been killed or have delayed leaf out and/or blooming compared to buds on the opposite side of the plant. These plants may need time to recover or a light pruning if injury is severe.

-

Sow seeds and plant annual and vegetable transplants after the last chance of frost. For best results, make sure plants are hardened off prior to transplanting. Gradually move plants into more light and allow exposure to cooler night temperatures over the course of a week. Planting on a cooler, overcast day also helps reduce transplanting stress.

-

Sow a wildflower patch or meadow. Look for mixes developed to support local pollinators. When choosing plants for pollinators, keep in mind that a variety of shapes, sizes, and colors helps to attract different pollinators. Bees are attracted to blue and yellow flowers while butterflies are typically attracted to red, orange and yellow.

-

Practice proper planting techniques. A planting hole should be as deep as the plant is in the container and 2-3x as wide. It is also good practice to cut circling roots to encourage outward root growth. When backfilling the hole, do not over-compress the soil; a good method to ensure the soil settles well is to fill the hole half way with soil and water it in, then fill the hole the rest of the way and water again. This makes sure that the soil is not over-compacted. It is very important to regularly water newly installed plants.

-

Prune spring flowering shrubs, such as forsythia, after they have bloomed. Many spring blooming species begin to develop flower buds for the next season in early summer of the previous year. Pruning immediately after flowering ensures that next year’s bloom will not be adversely affected by incorrect pruning time. Along with forsythia, azaleas, rhododendron, weigela, and lilac should be pruned after flowering.

-

Continue landscape bed prep and maintenance. Summer and fall blooming perennials should be divided by early May. Mulching helps add organic mater to the soil, buffers temperature fluctuations, helps control weeds, and reduces soil water loss. Mulch should not be applied greater than 4” and should be kept away from the base of trees and shrubs.

-

Bring houseplants outside. The end of the month is a good time to let houseplants get some fresh air! Similar to vegetable and annual transplants, houseplants will need time to acclimate to brighter outdoor light. Start by bringing them to a shaded spot, such as a covered porch, and gradually expose them to more sunlight (except plants that prefer shade which need to remain protected). Too much light too quickly can result in leaf burn and plant stress.

-

Be on the lookout for ticks. It is always important when working or playing outdoors to check for ticks. Defense against ticks can include perimeter yard treatments, repellents, and clothing treated with repellent. Regardless of defense method, a daily tick check is a good habit. If you have been bitten by a deer tick, consider sending it for testing for any tick-associated diseases to the UMass Laboratory of Medical Zoology – info at https://www.tickreport.com.

Mandy Bayer, Extension Assistant Professor of Sustainable Landscape Horticulture, University of Massachusetts Amherst

Timely Topics

Pruning Flowering Shrubs

Pruning is the selective removal of some parts of the plant for the benefit of the remainder. Some of the reasons for pruning flowering shrubs are:

- to maintain plant vigor and encourage the desired plant form (size and shape)

- to promote plant health by increasing air circulation to reduce the incidence of fungal diseases; removing dead or dying branches and branches injured by disease or insect infestation, broken branches, and branches that rub together

- to create and maintain good structure and plant appearance by removing unwanted branches, water sprouts and suckers

- to improve the quality and quantity of flowers and fruits.

When to prune

Spring flowering shrubs such forsythia, viburnum, honeysuckle, and lilac are generally pruned soon after flowering. They form their flower buds in mid to late summer and flower the following spring on one year old shoots that grew the previous summer. Pruning these in early spring, late summer or fall removes the flower buds and reduces the number of flowers in the spring. However, if full display of flowers is not important to you, then spring pruning is not a problem.

Summer and fall flowering shrubs such as panicle hydrangea, butterfly bush, buttonbush, summersweet clethra, sweetspire, and summer flowering spirea are generally pruned in early spring. These shrubs form their flower buds on new wood that grew in the spring of the current year. Pruning these in winter or early spring leads to vigorous stem growth in spring and summer that contains buds that will flower in summer and early fall. DO NOT prune spring- or summer-flowering shrubs in late summer or early fall since this will stimulate new growth that may not harden off before the winter. This may lead to winter cold injury. However, you can prune off dead, diseased or damaged branches or shoots at any time. Newly planted shrubs should not be pruned unless the branches are damaged because they need all their leaves to photosynthesize, which encourages root growth.

How to prune

There are two techniques for pruning shrubs.

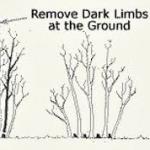

Renewal pruning: For older or overgrown shrubs, every year remove about one-third of the oldest, thickest stems or trunks, taking them right down to the ground to a height of 2-3 inches. This will encourage the growth of new stems from the roots. The first year, remove one-third of the oldest, unproductive branches. The next year, take one-half of the old, lingering stems. Finally, in the third year, prune out the remainder of the old branches. Once there are no longer any thick, overgrown trunks left, repeat every 2-3 years. Well-pruned shrubs should contain stems of varying ages. This method takes longer to complete, but the shrub stays more attractive throughout the rejuvenation period.

Renewal pruning: For older or overgrown shrubs, every year remove about one-third of the oldest, thickest stems or trunks, taking them right down to the ground to a height of 2-3 inches. This will encourage the growth of new stems from the roots. The first year, remove one-third of the oldest, unproductive branches. The next year, take one-half of the old, lingering stems. Finally, in the third year, prune out the remainder of the old branches. Once there are no longer any thick, overgrown trunks left, repeat every 2-3 years. Well-pruned shrubs should contain stems of varying ages. This method takes longer to complete, but the shrub stays more attractive throughout the rejuvenation period. - Rejuvenation pruning: Deciduous shrubs that have multiple stems (e.g. spirea, forsythia, honeysuckle, hydrangea,) and that have become very overgrown or neglected can be rejuvenated by cutting all canes back as close to the ground as possible in early spring. The season's flowers are sacrificed but the benefits from bringing the plants back to their normal size and shape outweigh this. Within one growing season, these shrubs will look like new plantings, full and with a natural shape. Many new shoots will grow from the base, which may require thinning.

Geoffrey Njue, UMass Extension Sustainable Landscapes Specialist

News for Gardeners

Dieback on Broadleaf Evergreens

Broadleaf evergreens like rhododendrons, hollies, Leucothoe and mountain laurels took a beating this winter, in spite of what seemed to be an overall mild season. Many are exhibiting leaves have bronzed or turned completely brown. In the case of Rhododendrons, whole sections of plants appear wilted and dying. What has happened and how should these plants be treated? Should the affected parts be pruned out?

It’s likely that a combination of factors contributed to the damage being widley seen this spring, some of which is also being seen on conifers. While the winter overall was generally mild, and we had limited snow accumulations, the mild periods were punctuated with cold, and we experienced many windy days. Additionally, excessive moisture in the previous growing season may have contributed to root loss in poorly drained soils. In the case of many of the broadleaf evergreens such as hollies, mountain laurel and Leucothoe, damaged leaves are most likely due to the extremely windy conditions, coupled with variable temperatures. Unseasonably low temperatures in early March, when the sun was strengthening and days were growing longer, warmed leaf tissue, which then lost moisture through transpiration at a time when soils were frozen and the moisture could not be replenished.

Additionally, several days with winds of exceptional vigor (February 25th was notable for the particularly persistent wind with gusts between 40 and 60mph) contributing to moisture loss, again, when plants were unable to replenish. Looking even further back, November temperatures were colder than normal, while early January was unusually warm (58 degrees in Boston on January 1st). Snow cover, which serves as an insulator helping to moderate soil temperature, was notably absent in many regions, allowing for repeated freeze thaw cycles that can cause root injury in particularly shallow rooted plants like Kalmia, Rhododendron and Magnolia. Reports of the upper portions of plants showing browning and dead leaves, while lower and interior leaves remain unscathed, suggests that the injury on these plants is due to wind and cold temperatures and that those portions unaffected were protected by the limited snow cover or shielded by the remaining portions of the plant. In these cases, it’s quite possible that the damaged foliage will be lost but the wood and buds are still viable. Before pruning, check to see if stems are alive by scratching the bark with your thumbnail to see if the underlying wood is still green – if so, wait until late May or early June before pruning so that you can assess which parts remain alive. At that point, if portions fail to leaf out, prune back until you find living wood. Make a sloped pruning cut, ¼” above and sloping way from an outward facing shoot or bud.

If the wood and inner bark on damaged shoots are brown, examine the length of the stem to see if you find any breakage, signs of borers, or sunken, dark areas in the bark that might indicate of a pathogen like Botryosphaeria. The many species of Botryosphaeria affect a wide array of plants, including Rhododendron, Ilex, Acer, Malus, Prunus and Cornus. Damage can be seen throughout the year as foliage wilts and turns brown, or when branches fail to break dormancy in spring. The pathogen usually enters the vascular system through an injury or opening created by pruning, breakage, insect or deer damage, or other physical damage caused by weather or pests. It can remain in the plant, asymptomatic, until the plant is weakened by another stress. Signs of Botryosphaeria include sunken, dark-brown cankers along, and sometimes girdling, stems. The diseased wood is stained reddish-brown and, when cut in cross-section, may display a wedged-shaped darkened area. Tiny fungal fruiting structures dot the bark and spores are dispersed during wet periods, either by rain or overhead irrigation. Spores can also be transported by insects and pruning tools. Prune well below the damage, to an outward facing shoot or bud, or to the ground, and destroy any infected leaves and branches. Good fall or early winter cleanup around infected plants helps reduce subsequent infections, as spores overwinter in infected leaves and branches.

Rhododendron borer (Synanthedon rhododendri) damage often manifests itself during the growing season, but impacted shoots further stressed by winter conditions may show the effect this time of year. Look for the entry holes near the ground or in crotches of branches along the stem. When the borer is active in mid-late summer and again in early spring, frass and/or sawdust appear from the hole and may accumulate on the ground. Entrance and exit holes can be seen along the branches and can be pruned out and destroyed when larvae are in residence. The larvae pupate for two weeks in May with adult wasp-like clearwing moths emerging from late-May into early June. After mating, females restart the cycle by laying eggs near former tunnels, near pruning cuts, or in branch crotches. When the pupae emerge, they tunnel into the stem and begin feeding, and will overwinter in stems.

The sporadic dead branches visible throughout large and established rhododendrons may also be caused by root and crown rot from Phytophthora infection. Phytophthora is an organism that persists in poorly-drained, water-logged soils and proliferates when temperatures and moisture is high – just the conditions we experienced last summer and into the fall. It often gains a foothold when plants are planted too deeply, or in soils that are overly wet or compacted. Some plants experience stunted growth as Phytophthora spreads, followed by sudden branch die-back. Small areas of damage can be pruned out and, if excessive moisture is alleviated, the plant may survive. Heavily damaged plants are best removed as fungicides provide little relief from this organism. This disease persists in the soil, entering the root system and spreading upward, destroying the vascular system as it travels. Susceptible species, including Acer, Fagus, Ilex, Juniperus, Malus, Pieris, Prunus and Taxus should not be replanted where Phytophthora issues have been encountered. The damage to well-established plants that was seen this past winter may be the result of changing conditions – either locally around individual plants, or the broader changes to climate which have resulted in longer, wetter periods, extreme storms, and warmer than usual temperatures. These temperature and moisture shifts, combined with other environmental stresses, make it more important than ever to choose plants that are able to withstand a broad range of conditions. Those that are most sensitive to extremes are likely to be less successful in modern landscapes.

Joann Vieira, Director of Horticulture, The Trustees of Reservations

Trouble Maker of the Month

Getting it Right with Grub Control

White grubs are insect larvae that are common lawn pests in southern New England. Grubs are capable of causing substantial turf damage either directly, by feeding on the roots of turfgrass plants, or indirectly, by serving as a food source for various critters such as moles, skunks, or crows which can disrupt the turf surface in pursuit of a grub meal. Uncertainty often exists about how to most effectively manage damaging grub populations with insecticides.

White grubs are insect larvae that are common lawn pests in southern New England. Grubs are capable of causing substantial turf damage either directly, by feeding on the roots of turfgrass plants, or indirectly, by serving as a food source for various critters such as moles, skunks, or crows which can disrupt the turf surface in pursuit of a grub meal. Uncertainty often exists about how to most effectively manage damaging grub populations with insecticides.

Grubs are the larvae of scarab beetle species such as Japanese beetles, Oriental beetles and others. The general life cycle for scarab beetles in New England is as follows: adult beetles fly and mate in early summer (typically in the weeks around the Fourth of July), and lay eggs shortly thereafter that hatch into larvae from July into August. Larvae (grubs) feed and grow into the fall and eventually move down in the soil to overwinter in the larval stage. In the spring, large grubs migrate back up in the soil profile and continue to feed before undergoing a transition period (called pupation) in June to become adult beetles and complete their life cycle.

The first-line of defense against grubs is to employ appropriate cultural practices in terms of mowing, fertilization and irrigation to maintain a healthy, resilient turf better equipped to handle grub pressure. As with other insect pests, there are two general approaches for actively controlling grubs. Curative controls are applied in response to visible damage, while preventive controls are applied before damage occurs in an effort to stop grub populations from reaching damaging levels.

Curative insecticides, while widely available, are best utilized only as a last resort when grub damage or associated foraging is visible and severe. Two main options currently exist for homeowners: materials containing trichlorfon (DyloxTM) or carbaryl (SevinTM). While these materials act quickly and do not remain active for an extended period of time in the soil, several drawbacks exist for their use. Bear in mind that these materials do not control beetle adults, grub eggs, or grub pupae, which leaves only two short application windows in the spring and late summer to control the larvae, and both are best applied during times when grubs are larger and more resilient, which translates to reduced effectiveness.

The effectiveness of carbaryl and trichlorfon can be reduced by water with a high pH (typically 7.2 or greater), which is typical of many municipal water supplies, and trichlorfon is sensitive to lower soil temperatures, which can reduce effectiveness earlier in spring or in late summer/early fall. Research has shown carbaryl in particular to be very inconsistent in terms of performance against grubs. Carbaryl is extremely toxic to bees and other pollinators, and both materials have greater potential animal and human toxicity relative to the preventive materials available today. Neither carbaryl nor trichlorfon are permitted for use on school grounds in Massachusetts.

These days, preventive control for grubs is vastly preferred to curative options. The objective is to have a material in place in the soil at the time when eggs hatch in July and August, as this is the time when the grub larvae are tiny and most vulnerable. For preventive control, current options for homeowners break down to two general categories: chlorantraniliprole, also known as AceleprynTM or GrubExTM, or a neonicotinoid compound (of which imidacloprid, or MeritTM, is the most frequently encountered).

Application timing is critical in order to achieve effective preventive control and varies depending on the product. Apply too early, and the product may break down before eggs hatch… apply too late, and the grubs may be too large to be satisfactorily affected by the product. Chlorantraniliprole (GrubExTM) takes 60-90 days to fully activate in the soil, so it is best applied in May in this region. Neonicotinoids like imidacloprid (MeritTM) activate much more rapidly, and therefore are best applied in July. Imidacloprid provides excellent control of several species of white grubs with the exception of Asiatic garden beetles (AGB), so populations primarily consisting of AGB must be managed with other means of control.

There are three additional important considerations for preventive control: The first is that preventive controls should only be applied to lawn areas with a history of grub damage, as opposed to indiscriminately as a form of ‘insurance’. The second is that neonicotinoid materials such as imidacloprid have the potential to harm pollinators, so special care must be taken to protect pollinators when using neonicotinoid insecticides for grub control - refer to our Neonicotinoid Turf Insecticides and Pollinators fact sheet at http://ag.umass.edu/turf/fact-sheets/neonicotinoid-turf-insecticides-pollinators. Finally, all materials for grub control, whether preventive or curative, must be watered in thoroughly according to label directions, as adequate water is required to move the material from the surface down into the soil where the grubs live.

Jason D. Lanier, UMass Extension Turf Specialist

Plant of the Month

Halesia carolina (Halesia tetraptera), Carolina silverbell

Halesia carolina is a small deciduous tree growing 30-40’ tall with a spread of 20-35’. Native to North America, it is found mostly in the Piedmont and mountains of the Carolinas, Tennessee, Georgia and Alabama. Smaller populations can be found as far west as Oklahoma and as far north as Ohio. In its natural setting, Carolina silverbell is an understory tree found growing along streams and moist slopes. In the landscape, plants have a broad to rounded, irregular crown with low forming branches.

Its common name comes from the white, bell-shaped, pendulous flowers that appear in early to mid-May. The flowers are primarily white; however, several pink forms are available. Flowers form in small clusters of 2-5. To fully appreciate the flowers, trees should be placed in the landscape for close viewing such as along a walkway, or near a deck or patio. Flowers develop into four winged drupes that change from green to brown in fall. The foliage is dark green in summer, turns yellow-green to yellow in fall, and defoliates relatively early. The bark is gray with white streaks when young, becoming ridged and furrowed with age.

Carolina silverbell is a wonderful small tree for the landscape, but also is appropriate in a mixed shrub or woodland border. This underutilized tree deserves more attention and has great versatility. Trees prefers rich, moist, well drained acidic soils in part shade to full sun. Unlike many other species, Carolina silverbell will flower profusely even in part shade. Plants are hardy in USDA zones 4-8 and rarely have insect of disease problems.

Cultivars:

‘Arnold Pink’ – rose-pink flowers, introduced by Arnold Arboretum

‘Meehanii’ – rounded shrub form

‘Savannah River’ – precocious, heavy flowering selection

‘Rosea’ – pink flower form

Related species or sub species

Halesia diptera

Halesia monticola

Halesia parviflora

Russ Norton, Agriculture & Horticulture Extension Educator, Cape Cod Cooperative Extension

Additional Resources

Landscape Message - for detailed timely reports on growing conditions and pest activity

Home Lawn and Garden Resources

Find us on Facebook! www.facebook.com/UMassExtLandscape/

Follow us on Twitter for daily gardening tips and sunrise/sunset times. twitter.com/UMassGardenClip

Diagnostic Services

The UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab provides, for a fee, woody plant and turf disease analysis, woody plant and turf insect identification, turfgrass identification, weed identification, and offers a report of pest management strategies that are research based, economically sound and environmentally appropriate for the situation. Accurate diagnosis for a turf or landscape problem can often eliminate or reduce the need for pesticide use. Sampling procedures, detailed submission instructions and a list of fees.

The UMass Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory at the University of Massachusetts Amherst provides test results and recommendations that lead to the wise and economical use of soils and soil amendments. The Routine Soil Analysis fits the needs of most home gardeners. Sampling procedures plus the different tests offered and a list of fees.

Spread the Word!

Share this newsletter with a friend! New readers can subscribe to our Home Gardener E-Mail List.