Spongy Moth

![]() Download this fact sheet as a PDF

Download this fact sheet as a PDF

Pest: Spongy Moth (Lymantria dispar)

Order : Lepidoptera

Family : Erebidae (formerly the Lymantriidae)

Host Plants:

White oak is the preferred host, but most other oak species (in the Northeast) are also highly susceptible, as well as many other deciduous species. This includes maple, birch, poplar, willow, apple, hawthorn, and many others. Conifers, such as pine and spruce, may also be attacked when the preferred host plants are in short supply. While many trees can survive a year of defoliation from Lymantria dispar if they are otherwise healthy, consecutive years of defoliation can highly stress host trees. These stressed plants then become more vulnerable to secondary pests, such as certain wood-boring insects and decay fungi.

Description:

Spongy moth (Lymantria dispar), the insect formerly known as gypsy moth, accidentally escaped the home of E. Leopold Trouvelot and was introduced into the US in Medford, Mass. in the late 1860’s. He had intentionally brought it to his home in Massachusetts, from France, to study the insect with an interest in silk production. Since then, Lymantria dispar has spread throughout the Northeast and well beyond. It can be a serious pest of trees and a nuisance due to the irritating hairs on its body and the copious amount of excrement (frass) that it produces in high population years.

The Pest:

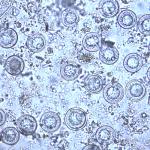

The moth overwinters as an egg in a cluster of 500 or more eggs (Figures 1 and 2). Eggs typically hatch in the spring during the first week in May in Massachusetts, but variations in climate and spring weather can either accelerate or delay egg hatching. Once hatched, the tiny, hairy caterpillars may remain in the lower forest canopy or, when in high populations, migrate upwards to the tree tops, where each one then spins down on a long silken thread. The tiny caterpillars hang in the air waiting for a strong wind to break the thread and carry them to a new location. This process of dispersal is known as “ballooning” and is somewhat common in caterpillar species where the adult females do not fly. It is the only silk that this species produces. Lymantria dispar caterpillars do not make silken webs or tents. This type of dispersal helps young larvae relocate to more favorable hosts, such as oaks, while factors such as food quality (species composition) and the availability of suitable areas to hide during the day (such as in rough oak bark) may affect Lymantria dispar moth dispersal patterns. Population sizes of this pest can change dramatically from one year to the next.

Once the caterpillars settle on a new host, they begin feeding on the foliage. Small to moderate sized populations will often feed at night and come down out of the trees during daylight hours to avoid predators and parasites. Caterpillars in high populations usually stay in the trees around the clock due to intense competition for foliage.

While Lymantria dispar caterpillars are only 1/16 of an inch in length when they hatch, they may exceed 3 inches in length by the time they pupate, usually about six weeks later. The caterpillars have hairy bodies; along the length of their backs, they have five pairs of blue dots followed by six pairs of red dots (Figure 3). The caterpillar stage typically lasts until about the third week in June in Massachusetts, whereupon they pupate (Figure 4). Adults start to appear by late June/early July. Neither the male nor female adult moths feed.

Adult male Lymantria dispar moths are brown with black markings and have highly feathered antennae (Figure 5). Female moths are white with black markings and have straight, threadlike black antennae; female European Lymantria dispar moths do not fly (Figure 1). Lymantria dispar caterpillars have numerous hairs on their bodies, as do the adults. A small percentage of the population reports experiencing allergy-type reactions to these hairs. Symptoms range from itchy skin irritation to sinus allergies with itchy eyes and a runny nose. For most people, Lymantria dispar does not cause allergic reactions as readily as certain other hairy caterpillars (ex. browntail moth).

Management Strategies:

Once the caterpillars have settled to feed, they can be successfully treated with Bacillus thuringiensis (kurstaki), commonly known as B.t.k. This is a naturally occurring bacterium that is specific to caterpillars that become moths or butterflies (Lepidoptera). It is relatively safe for beneficial organisms and other insects. A commercial, Massachusetts licensed pesticide applicator will be needed to apply B.t.k to larger trees due to the necessary application equipment required. However, once the caterpillars are older, B.t.k is much less effective. To establish whether B.t.k will work or not, inspect the caterpillars on the host plant; younger Lymantria dispar caterpillars have a head capsule that is all black while the older ones have obvious yellow markings on the head - these larvae are less susceptible to B.t.k. In this case, other compounds, such as spinosad, may be necessary.

Even though numerous chemical pesticides are available, it is best to manage problematic populations of this pest early and utilize B.t.k as necessary to minimize the risk to non-target organisms and the environment, when possible. Other active ingredients labelled for use on Lymantria dispar include acephate, acetamiprid, azadirachtin, Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. aizawai, carbaryl, emamectin benzoate, insecticidal soap, permethrin, and tebufenozide. Horticultural oils may manage Lymantria dispar eggs and very young larvae but thorough coverage is necessary. This may be difficult to achieve on egg masses hidden in protected areas and on branch undersides. Egg masses may be scraped into a can of soapy water, however, this is time consuming and labor intensive and only possible for egg masses within reach.

Traps for the adults offer no benefits whatsoever in managing this pest. While traps and bands around trees may be useful for monitoring this insect, they do not offer effective management of Lymantria dispar, especially in high population years.

During wet springs, an entomopathogenic (i.e. insect killing) fungus known as Entomophaga maimaiga, works extremely well in keeping this pest in low numbers. This fungus is now “naturally” common in Massachusetts. It may have been introduced into the United States from Japan in 1910 for gypsy moth management, but the actual fungus we have today seems to be from a later introduction. Observing dead Lymantria dispar caterpillars hanging head-down on the trunks of host trees is a good indicator that this fungus has been effective (Figure 6). The nucleopolyhedrosis (NPV) virus is also a common cause for the collapse of Lymantria dispar populations. Both the fungus and virus overwinter in the soil in Massachusetts and require ample amounts of moisture in the spring to build up in Lymantria dispar caterpillar populations.

Natural enemies of Lymantria dispar caterpillars include various insects and mammals, and some birds. Certain ants, ground beetles, and parasitoid wasps and flies will attack Lymantria dispar in different life stages (caterpillars or pupae). Mice will also feed on caterpillars and pupae.

Written by: Robert Childs

Updated by: Tawny Simisky, Extension Entomologist, UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, & Urban Forestry Program