Happy Fall Equinox!

UMass Extension's Landscape Message is an educational newsletter intended to inform and guide Massachusetts Green Industry professionals in the management of our collective landscape. Detailed reports from scouts and Extension specialists on growing conditions, pest activity, and cultural practices for the management of woody ornamentals, trees, and turf are regular features. The following issue has been updated to provide timely management information and the latest regional news and environmental data.

Registration is still open for our UMass Extension GREEN SCHOOL!

Green School is going VIRTUAL for 2020! Classes will be Oct. 26 - Dec. 10.

Green School is going VIRTUAL for 2020! Classes will be Oct. 26 - Dec. 10.

This comprehensive 12-day certificate short course for Green Industry professionals is taught by UMass Extension specialists, University of Massachusetts faculty, and guest presenters.

Three Specialty Tracks Are Offered:

* Landscape Management

* Turf Management

* Arboriculture - specifically geared toward professional arborists

Find the full schedule and registration info at http://ag.umass.edu/greenschool

For eligible employers in Massachusetts, the registration fee may be partially reimbursed (up to 50%) through the Massachusetts Workforce Training Fund Express Grant Program. Employers should submit an online application to the Express Grant program at least 4 weeks in advance of Green School's starting date. To find out if you qualify and to apply for benefits, go to http://workforcetrainingfund.org/apply/express-program/.

To read individual sections of the message, click on the section headings below to expand the content:

Scouting Information by Region

Environmental Data

The following data was collected on or about September 16, 2020. Total accumulated growing degree days (GDD) represent the heating units above a 50° F baseline temperature collected via our instruments for the 2020 calendar year. This information is intended for use as a guide for monitoring the developmental stages of pests in your location and planning management strategies accordingly.

|

MA Region/Location |

GDD |

Soil Temp |

Precipitation

|

Time/Date of Readings |

||

|

2-Week Gain |

2020 Total |

Sun |

Shade |

|||

|

CAPE |

239.5 |

2438.5 |

65 |

60 |

0.99 |

12:00 PM 9/16 |

|

SOUTHEAST |

228 |

2604 |

78 |

63 |

0.15 |

3:00 PM 9/16 |

|

NORTH SHORE |

228.5 |

2517 |

62 |

57 |

1.46 |

9:30 AM 9/16 |

|

EAST |

246.5 |

2759 |

74 |

65 |

0.59 |

5:00 PM 9/16 |

|

METRO |

208 |

2509 |

57 |

55 |

0.83 |

6:30 AM 9/16 |

|

CENTRAL |

223 |

2544 |

52 |

52 |

0.98 |

7:00 AM 9/16 |

|

PIONEER VALLEY |

213 |

2521.5 |

64 |

59 |

1.29 |

1:00 PM 9/16 |

|

BERKSHIRES |

177 |

2263.5 |

63 |

57 |

0.90 |

8:30 AM 9/16 |

|

AVERAGE |

220 |

2520 |

64 |

59 |

0.90 |

_ |

|

n/a = information not available |

||||||

Updated as of 9/17, this map shows 4 categories of drought plaguing MA: https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?MA

Water use restrictions, bans and emergencies are still in effect in a great many towns. Updated regularly, check the MassDEP map: https://www.mass.gov/doc/water-use-restrictions-map/download

Phenology

| Indicator Plants - Stages of Flowering (BEGIN, BEGIN/FULL, FULL, FULL/END, END) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PLANT |

CAPE |

SE |

NS |

EAST |

METRO |

CENT |

PV |

BERK |

|

Heptacodium miconioides (seven-son flower) |

Begin |

* |

Begin/Full |

Begin/Full |

Begin |

Begin/Full |

Begin/Full |

* |

|

Clematis paniculata (sweet autumn Clematis) |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

|

Polygonum cuspidatum (Japanese knotweed) |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

| * = no activity to report/information not available | ||||||||

Regional Notes

Cape Cod Region (Barnstable)

General Conditions: The average temperature between 9/3 and 9/16 was 67˚F with a high of 86˚F on September 4 and a low of 45˚F on September 15. The period began with summer like weather but has ended with relatively cool conditions with several nights in the low 50s and even into the mid-40s. The two-week period has had several multi-day stretches of both cloudy and sunny days. Almost an inch of precipitation fell during the period in basically two events, one on September 2 and 3 and the other on September 11. The rain was welcomed, however not sufficient enough to have any significant impact on soil moisture. Top soil moisture and sub soil moisture is dry. The US drought monitor has listed Cape Cod as in severe drought since September 1: https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?MA

Pests/Problems: The primary issue in the landscape is plant stress due to low soil moisture, high temperatures and windy conditions. Wilting, scorch, premature defoliation, and plant failure are seen in unirrigated and some irrigated landscapes. Dry conditions are hampering the ability for turf renovation and seeding. Insects or insect damage observed during the period include Lecanium scale on numerous hosts (nymphs can be observed on leaves), pine tip moth damage to pitch pine and mugo pine, hemlock wooly adelgid and hemlock elongate scale on hemlock, black turpentine beetle damage to pitch pine, lacebugs on azalea, Andromeda, and sycamore, chilli thrips damage on bigleaf Hydrangea becoming more noticable, Hibiscus sawfly on Hibiscus, two spotted spidermite on butterfly bush and many other ornamentals, and sunflower moth damage to Echinaceae. Disease symptoms or signs observed during the period include powdery mildew on just about everything, scorch on horsechestnut as a result of Guignardia leaf blotch (https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/guignardia-leaf-blotch), cedar apple rust on crabapple, apple scab on crabapple, leaf spot of Rudbeckia, Cercospora leaf spot on bigleaf and oak leaf Hydrangea, and aster yellows on goldenrod. Crabgrass is flowering and cool season weeds can be seen germinating in bare spots in damaged turf.

Southeast Region (Dighton)

General Condition: Cooler weather has arrived and soils are now very dry. There are noticeably fewer pollinators foraging. Hummingbirds have left. Among the plants I've noticed flowering are: Reynoutria japonica, syn. Polygonum cuspidatum (Japanese knotweed), Soldago spp. (goldenrod), Oenothera biennis (common evening primrose), Eutrochium purpureum (Joe-Pye-weed), Eupatorium perfoliatum (common boneset), Clematis paniculata (sweet autumn Clematis), Phlox paniculata (garden Phlox), Rosa spp., ‘Knockout’ roses, Sedum spp., Sedum 'Autumn Joy', Symphyotrichum ericoides (white heath aster), Hosta spp., Echinacea purpurea (coneflower), Hydrangea paniculata (Hydrangea 'LimeLight') Salvia yangii (Russian sage), Rudbeckia spp. (black-eyed-Susan), Lagerstroemia spp. (crape myrtle), Hieracium lachenalii (common hawkweed), Albizia julibrissin (mimosa, silktree), Buddleia spp. (butterfly bush), Helianthus tuberosus (Jerusalem artichoke, sunchoke), and Franklinia alatamaha (Franklin tree).

Pests/Problems: This bears repetition - mosquito vectored diseases are the most serious issue in the landscape. In addition to multiple cases of Triple E on the Southcoast, there is now a report of a West Nile Virus infection in Fall River. As the season goes on, viruses will continue to build up in the available breeding pools. Mosquitoes will continue to be a threat until we have had a hard frost. Drought is the major concern for plants. Early color and leaf fall are evident. Dieback can be observed even in well-established plantings.

North Shore (Beverly)

General Conditions: In this reporting period, we experienced cooler temperatures. Daytime temperatures were mostly in the low to mid 70s with days earlier this week measuring in the low 60s.Temperatuatures above 80 degrees Fahrenheit were recorded on three days during this period. The average daily temperature during this two-week period was 66˚F, with the maximum temperature of 86℉ recorded on September 4 and the minimum temperature of 41℉ recorded on September 15. Two storms passed through the region dropping some much-needed rainfall. Approximately 1.46 inches of rainfall were recorded at Long Hill during this two-week period. Due to the rains received during this period and the cooler temperatures, turf grasses on lawns and landscapes have greened up and started to grow. Woody plants seen in bloom include: silk tree or mimosa (Albizia julibrissin), seven-son flower (Heptacodium miconioides), Franklin tree (Franklinia alatamaha), blue mist shrub (Caryopteris x clandonensis). Herbaceous plants seen in bloom include: garden Phlox (Phlox paniculata), Japanese Anemone (Anemone x hybrida), hardy Begonia (Begonia grandis), sweet autumn Clematis (Clematis paniculata) and oxeye sunflower (Heliopsis helianthoides).

Pests/Problems: Deer browsing was observed on some plants. Powdery mildew on dogwoods, garden Phlox and susceptible lilacs continue to persist. Crabgrass and other weeds are thriving in the landscape. Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis) is in full bloom and continues to thrive. Mosquitoes and ticks are still very active at dawn and dusk. Protect yourself with a repellent when you're out in the woods during early hours in the morning and late evening.

East Region (Boston)

General Conditions: Hot and dry conditions continued into September with several cooler mornings and reduced humidity. We experienced two rain events over the reporting period amounting to an insignificant 0.59” of precipitation. Early fall color has been observed on mature sugar maples.

Pests/Problems: The drought conditions are evident throughout the landscape. Premature leaf drop continues in unirrigated areas. Powdery mildew is prevalent on dogwood, lilac, peony and Phlox. Adult Viburnum Leaf Beetle continue to chew the leaves of susceptible Viburnum. Hibiscus sawfly have defoliated many hardy Hibiscus to the mid-rib. The majority of landscape plants are suffering from environmental stress and are highly susceptible to pests and disease.

Metro West (Acton)

General Conditions: The cooler temperatures have arrived but not without a day or two of warm summer-like temperatures recorded in these first few weeks of September to remind us that summer is not over yet until it officially ends on September 21st with fall equinox on September 22nd. September’s average rainfall is 3.77” and a total of 0.83” has been recorded for the month so far. Observed in some stage of bloom these past couple of weeks were the following woody plants: Buddleia spp. (butterflybush), Heptacodium miconioides (seven-son flower), Hibiscus syriacus (rose-of-Sharon), Potentilla fruiticosa (Potentilla) and Rosa 'Knockout' (Knockout family of roses). A woody vine in bloom is Clematis paniculata (sweet autumn Clematis). Contributing even more color and interest to the landscape are some flowering herbaceous plants including: Aster spp. (New England Aster, New York Aster, smooth Aster, white wood Aster), Caryopteris x clandonensis (blue mist shrub), Chasmanthium latifolium (northern sea oats), Chelone lyonii (pink turtlehead), Echinacea purpurea (coneflower) and its many cultivars, Gentian spp., Geranium sanguineum (cranesbill Geranium), Hemerocallis spp. (daylily), Hosta spp. (plantain lily), Kirengeshoma palmata (yellow wax bells), Miscanthus spp. (maiden grass), Panicum virgatum (switch grass), Patrinia gibbosa (Patrinia), Pennisetum alopecuroides (fountain grass), Perovskia atriplicifolia (Russian sage), Phlox carolina (Carolina Phlox), P. paniculata (garden Phlox), Physostegia virginiana (obedient plant), Platycodon grandiflorus (balloon flower), Rudbeckia fulgida var. sullivantii 'Goldsturm' (black-eyed Susan), Sedum ‘Autumn Joy’, S. ‘Rosy Glow’ (stonecrops), and Solidago spp. (goldenrod). Adding even more color and interest to the landscape are the following plants heavy with fruit, seed, berries, and nuts: Convallaria majalis (lily of the valley), Cornus (dogwood), Crataegus (hawthorn), Malus (crabapple), Rosa (rose) and Viburnum.

Pests/Problems: This area remains in a moderate drought according to the US Drought Monitor: https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?MA Needless to write, soils are dry and trees and shrubs are stressed and signs of this stress are evident including early fall color, leaf drop, wilting foliage, and canopy dieback.

Central Region (Boylston)

General Conditions: Aside from the lack of any significant precipitation, the end of summer weather has been nearly perfect. Day temperatures ranged from a low of 65˚F to a high of 81˚F, with overnight temperatures at times dipping into the low 40’s (dropping as low as 38˚F during the last night of the reporting period). There is much in bloom in the garden and in natural areas, with goldenrods like Solidago canadensis (Canada goldenrod) and S. rugosa (wrinkle-leaved goldenrod) revealing their typical end of season burst of color. Our native asters have also come to life, including Symphyotrichum novi-belgii (New York aster) and S. novae-angliae (New England aster). Fall foliage has begun to turn, with early color showing on Itea virginica (Virginia sweetspire) and Benthamidia (formerly Cornus) florida (flowering dogwood).

Pests/Problems: As of September 8, the US Drought Monitor indicated the region was suffering from moderate to severe drought. Since that time, we have received only 0.19 inches of rainfall. The long-range forecast shows no chance of precipitation through the end of September. While not as severe as the wildfires engulfing much of the western United States, this year’s drought comes at a time when we are seeing widespread death and decline to oak trees due to previous drought and other environmental stresses like gypsy moth caterpillars. Without substantial rainfall before winter, drought stress will likely contribute to more decline of our oak canopy and will certainly cause damage or death in non-irrigated landscape plants.

Pioneer Valley Region (Easthampton)

General Conditions: Cool to mild temperatures have prevailed during the past week in the Pioneer Valley, as the heat of the summer appears to be in the rearview mirror. The below-average temperatures and cool nights of late are in stark contrast to the searing temperatures we experienced from mid-June to mid-August. Over the entire reporting period, high temperatures ranged from 88°F (9/8) to 69°F (9/15) while low temperatures have spanned 68°F (9/10) to 41°F (9/15). The cool, morning air over the warmer waters of the Connecticut River has been creating the wispy, rising “steam” (actually fog) that’s always interesting to see. There was a noticeable, milky haze to the sky on 9/15 and 9/16 as smoke from the western wildfires traveled through the upper atmosphere on the jet stream. Despite our dry conditions, we can be thankful that fires are uncommon and small in size here in the northeast. We had one significant rain event over this reporting period, with 0.9″ at the Easthampton gauge on 9/10. It was an exceptionally muggy day with dew points in the mid-70s and some soaking afternoon rainfall. Despite this, the first half of September continued the dry trend we’ve experienced all summer and total accumulation this month hovers around 1.5” at most stations. According to the NWS Climate Prediction Center, both the 6-10 day and 8-14 day outlook suggest below-average temperatures. Locally, low temperatures are forecasted to dip into the upper 30s this weekend (9/19 & 9/20) with pockets of frost developing in the hill towns. But for the majority of the Pioneer Valley, it appears our first frost is not yet on the horizon. Still, it is time to bring tender houseplants (Geraniums, tropical plants, etc.) inside, if they’ve been on the porch this summer. The cool nights and decreasing day length have really hammered down soil temperatures, with shade readings now in the 50s. Turfgrasses have responded accordingly and are greening and growing again. Of course, these are grasses with irrigation or significant shade, as unirrigated lawns in full sun are mostly brown. The lack of rain this season continues to be an issue and as we approach dormancy. Drought stress can result in a lack of proper cold acclimation for trees and shrubs, leading to winter burn and desiccation. Fall foliage is starting to develop, but at present there’s a sickly brown hue to some of the changing trees (mostly maples), owing to the dry conditions. Given the times, it seems fitting on some level. After the incredible foliage display of 2019, this autumn has a tough act to follow anyway. Dogwood, Viburnum and Euonymus leaves are reddening. Winterberries are turning, or starting to turn, their beautiful red color. Goldenrod is in full bloom along with various wild and cultivated asters. Fall planting season is in full swing and as nurseries clear out their annual inventory, there are some great deals to be had.

Pests/Problems: Despite the dry weather, some wood-rotting fungi continue to appear, like Ganoderma sessile (suspected, possibly G. curtisii), from a redbud stump on the UMass campus (see photo). The dry weather has made it difficult for some trees to resist vascular disease pathogens like Verticillium. When healthy, susceptible trees and shrubs can often defend against infection but when stresses mount, the pathogen can overtake the plant. If you suspect Verticillium wilt, scrape the bark away from stems and small branches to look for brown to olive-colored staining in the vascular tissue (pictured here on a Japanese maple stem). Grasshoppers were observed eating the foliage on herbaceous annuals and perennials. Moles, shrews and chipmunks continue to tunnel and make a mess of beds. Squirrels are very busy right now, snipping shoot tips on oaks and other hardwoods to build nests for the winter and capture acorns. Anecdotally, acorn production seems down this year for both white and red oaks, especially in comparison to the mast year in 2019 for red oak. Many late season foliar diseases common last fall are scarce this season but powdery mildews are abundant. Continue to irrigate newly transplanted trees and shrubs, but back off the interval, now that transpirational water loss is decreasing as temperatures drop. Rhododendron, boxwood and yews are sensitive to overwatering and can develop edema. The most prominent symptom of edema is the brown-colored blistering that appears on the underside of the foliage. But chlorotic foliage and thinning canopies can also develop.

Berkshire Region (Great Barrington)

General Conditions: The weather has taken a definite turn in the direction of autumn after hitting a peak high of 83˚F on September 8 In West Stockbridge. On the same day, the highs were 82˚F in Pittsfield and Richmond, and 85 in North Adams. Since then, daytime high temperatures have been mostly in the low 70s and 60s. The lowest temperatures during the past two weeks occurred on the morning of the 15th with 35˚F in West Stockbridge, 34˚F in Richmond, 37˚F in North Adams and 38 in Pittsfield. Some frost was observed that morning in the normally coldest spots in the Berkshires but frost was also observed in some areas where the temperature remained above freezing. This may be explained by the fact that cold, dense air sinks to ground level while the air above remains somewhat warmer. Unless the thermometer is right at ground level, it will not be registering the coldest air. Drought conditions continue with most of Berkshire County in the “Abnormally Dry” or “Moderate Drought” status as of September 8, according to the most recent update of the U.S. Drought Monitor report. Rainfall since the last Landscape Message report was 0.90” for West Stockbridge, 0.95” in Pittsfield, 0.97” in Richmond, and only 0.50” in North Adams. Perhaps more than photoperiod, the persistent drought has initiated an early start to the fall foliage season. Many trees are showing their fall color to some extent, though we are almost 4 weeks before peak fall foliage time. Despite the dry conditions, growth of turfgrass has not been much affected except where low mowing/no irrigation has been a normal practice.

Pests/Problems: As mentioned above, significant leaf drop has been observed. While drought has been a factor, foliar diseases have also played a role. Foliar diseases such as apple scab have resulted in pre-mature leaf drop of crabapples and apples for many weeks. Foliar diseases were also noticed on the dropped leaves of other species as well, including black cherry, sugar maple, horse chestnut, and some dogwoods. Verticillium wilt was observed on a smokebush (Cotinus) and a sugar maple. Few pests were observed during this week’s scouting. The most prominent pest was red mites on dwarf Alberta spruce and mites on dogwood. Inspection of the foliage of boxwood showed feeding activity by the boxwood leaf miner larvae. Despite the drought, slugs and snails were observed feeding on herbaceous perennials at one location. The site was irrigated, which may account for the intense activity of these pests. Wasp activity, especially yellow jackets, is high. In several instances, wasp nests were observed in lawn areas. Usually, the wasps are not of concern unless disturbed, such as when a lawn mower runs over their nest entrance. Also, keep in mind that the diet of wasps goes from “meat to sweet” at this time of year. There has also been an uptick in animal browsing by deer, woodchucks, chipmunks, rabbits, and voles.

Regional Scouting Credits

- CAPE COD REGION - Russell Norton, Horticulture and Agriculture Educator with Cape Cod Cooperative Extension, reporting from Barnstable.

- SOUTHEAST REGION - Brian McMahon, Arborist, reporting from the Dighton area.

- NORTH SHORE REGION - Geoffrey Njue, Green Industry Specialist, UMass Extension, reporting from the Long Hill Reservation, Beverly.

- EAST REGION - Kit Ganshaw & Sue Pfeiffer, Horticulturists reporting from the Boston area.

- METRO WEST REGION – Julie Coop, Forester, Massachusetts Department of Conservation & Recreation, reporting from Acton.

- CENTRAL REGION - Mark Richardson, Director of Horticulture reporting from Tower Hill Botanic Garden, Boylston.

- PIONEER VALLEY REGION - Nick Brazee, Plant Pathologist, UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab, temporarily reporting from Easthampton.

- BERKSHIRE REGION - Ron Kujawski, Horticultural Consultant, reporting from Great Barrington.

Woody Ornamentals

Diseases

Recent pests and pathogens of interest seen in the UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab https://ag.umass.edu/services/plant-diagnostics-laboratory:

- Dutch elm disease (DED), caused by Ophiostoma novo-ulmi, on Japanese elm (Ulmus davidiana var. japonica). The tree is approximately 10-years-old and has been present at the site for three years. The tree is surrounded by a residential lawn with full sun. For the past two years, the tree has exhibited flagging in the lower canopy. The submitted stems displayed vascular staining in last year’s (2019) wood, but this year’s tissue was free of any symptoms. The vascular staining in the 2019 wood encompassed almost the entire circumference of the stem. Despite the damage, the 2020 growth appeared robust. While Japanese elm is resistant to DED, and many cultivars available through the nursery trade are highly resistant, this species is not immune.

Stem and branch cankering caused by Botryosphaeria s.l. on linden (Tilia sp.), red oak (Quercus rubra), black tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica) and blue holly (Ilex × meserveae ‘Blue Princess’). The linden is mature (~50-years-old) and resides on a college campus surrounded by turf. This season, the tree exhibited undersized and browning leaves throughout the canopy. The red oak is mature (~80-years-old) and has stem dieback scattered throughout the canopy with visible stem and branch cankers. The tupelo is young (~10-years-old) and is one of seven trees planted in a row six years ago. The trees reside in a narrow strip in an urban setting above a retaining wall with a 4” gravel mulch layer and no supplemental irrigation. The holly is approximately 10- to 15-years-old and is part of a hedge planted along a driveway. The site is characterized as shaded and drought-prone. Lower canopy dieback was observed this season, with browning leaves and desiccated stems. The fungus was readily incubated from the submitted stems (see photo).

Stem and branch cankering caused by Botryosphaeria s.l. on linden (Tilia sp.), red oak (Quercus rubra), black tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica) and blue holly (Ilex × meserveae ‘Blue Princess’). The linden is mature (~50-years-old) and resides on a college campus surrounded by turf. This season, the tree exhibited undersized and browning leaves throughout the canopy. The red oak is mature (~80-years-old) and has stem dieback scattered throughout the canopy with visible stem and branch cankers. The tupelo is young (~10-years-old) and is one of seven trees planted in a row six years ago. The trees reside in a narrow strip in an urban setting above a retaining wall with a 4” gravel mulch layer and no supplemental irrigation. The holly is approximately 10- to 15-years-old and is part of a hedge planted along a driveway. The site is characterized as shaded and drought-prone. Lower canopy dieback was observed this season, with browning leaves and desiccated stems. The fungus was readily incubated from the submitted stems (see photo). Blue spruce dieback (Picea pungens ‘Mrs. Cesarini’) caused by Setomelanoma holmii and Phomopsis. Dwarf, mounded blue spruce cultivar with very dense growth habit. Plant is seven-years-old and has been present at the site for only six months. This summer, the tree exhibited needle browning, shedding and stem dieback. It resides in full sun with overhead irrigation. Setomelanoma has been associated with sudden needle drop (SNEED) of spruce in several Midwestern states. While the fungus is a known plant pathogen, its role in the decline of landscape blue spruce remains unclear. As this case illustrates, rarely is one insect or pathogen present on declining spruce. Phomopsis has been associated with blue spruce decline throughout the region and is more common on landscape samples. The needles were pale green to brown and desiccated, but no needle pathogens (Rhizosphaera and Stigmina) were detected.

Blue spruce dieback (Picea pungens ‘Mrs. Cesarini’) caused by Setomelanoma holmii and Phomopsis. Dwarf, mounded blue spruce cultivar with very dense growth habit. Plant is seven-years-old and has been present at the site for only six months. This summer, the tree exhibited needle browning, shedding and stem dieback. It resides in full sun with overhead irrigation. Setomelanoma has been associated with sudden needle drop (SNEED) of spruce in several Midwestern states. While the fungus is a known plant pathogen, its role in the decline of landscape blue spruce remains unclear. As this case illustrates, rarely is one insect or pathogen present on declining spruce. Phomopsis has been associated with blue spruce decline throughout the region and is more common on landscape samples. The needles were pale green to brown and desiccated, but no needle pathogens (Rhizosphaera and Stigmina) were detected.- Leaf scorch on common lilac (Syringa vulgaris) due to suspected heat stress. Row of mature plants, approximately 6’ tall at time of installation five years ago. Full sun setting atop a hillside and next to a patio wall. Drip irrigation is provided to plants. During the hot and humid weather this summer, interveinal browning and a marginal scorch developed on one of the five plants in the row. Over 90% of the leaves were affected. No pathogens or insect pests were associated with the damage. Heat stress symptoms on the foliage occurs when plants cannot effectively cool the leaf tissue through convective and radiative heat loss and is often associated with drought stress. However, in this case the plants were receiving supplemental water.

- Leaf browning and decline of Fastigiate European hornbeam (Carpinus betulus ‘Fastigiata’) caused by girdling roots, heavy clay soils and stem cankering from Melanconis and Phomopsis. Tree is approximately 15-years-old and has been present at the site for 10 years. Tree resides in a narrow, urban bed with full sun, drip irrigation and compacted, heavy clay soils. In early August, a rapid browning of the leaves throughout the canopy developed. European hornbeam, like most trees, prefers well-drained soils but can tolerate a range of soil types. While the root flare was clearly visible, excavation around the tree revealed some significant girdling roots. Submitted branch segments were harboring two fungal pathogens, Melanconis and Phomopsis. Both are opportunistic and produce huge masses of asexual spores that are readily dispersed, but the latter is far more common in the landscape.

- Wilt and decline in the canopy of a mature Japanese maple (Acer palmatum) caused by stem/branch cankering (Botryosphaeria and Phomopsis) and maple anthracnose (Aureobasidium apocryptum). Tree is approximately 15-years-old and has been present on the site for over five years. In July, foliage started browning and wilting and the symptoms have since spread throughout the canopy. The tree receives full sun but has old storm damage and a trunk wound and a nearby lawn sprinkler system that sprays directly on the trunk. Established populations of Botryosphaeria and Phomopsis are bad enough on their own, but when the duo is present, some serious damage can ensue. Free moisture from overhead sprinklers allows the fungi to sporulate and readily spread through splashing water.

- Thinning canopies and premature needle shedding on Norway spruce (Picea abies) caused by Phomopsis and Rhizosphaera. A row of 12 trees, approximately 40-years-old, at a residential property in full sun that was recently re-landscaped. The trees are located on the border of the property and in close proximity to the ocean. Submitted shoots had needles that were pale green to brown and readily shedding. As is often the case, there were no visible symptoms of stem cankering but once the bark was shaved, vascular discoloration was visible. Rhizosphaera was also easily incubated from the dying and dead needles. The ample moisture along the coast helped to facilitate both the stem cankering and needle blight infections.

Report by Nick Brazee, Plant Pathologist, UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab, UMass Amherst.

Insects

Did you miss the live broadcasts of UMass Extension’s Invasive Insect Webinar Series? No problem! View the archived recordings of all seven webinars here:https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/invasive-insect-webinars

Did you miss my recent webinar with Urban Forestry Today and Dr. Rick Harper? No problem! View the archived recording of this webinar, along with many others, here: http://www.urbanforestrytoday.org/webcast-archives.html

Interested in learning more about insect identification and life cycles? Only have 3 minutes or less? Check out InsectXaminer! https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/insectxaminer

Insects and Other Arthropods of Public Health Concern:

- Mosquitoes: On July 3, 2020 the Massachusetts Department of Public Health announced that the eastern equine encephalitis (EEE) virus had been detected in mosquitoes in Massachusetts for the first time this year: https://www.mass.gov/news/state-public-health-officials-announce-seasons-first-eee-positive-mosquito-sample-0 . For more information about the first 2020 EEE detection and ways to protect yourself, visit the link above.

For current information, including searchable risk maps for both EEE and WNV in Massachusetts, visit:https://www.mass.gov/info-details/massachusetts-arbovirus-update

According to the Massachusetts Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Science and the Department of Public Health, there are at least 51 different species of mosquito found in Massachusetts. Mosquitoes belong to the Order Diptera (true flies) and the Family Culicidae (mosquitoes). As such, they undergo complete metamorphosis, and possess four major life stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Adult mosquitoes are the only stage that flies and many female mosquitoes only live for 2 weeks (although the life cycle and timing will depend upon the species). Only female mosquitoes bite to take a blood meal, and this is so they can make eggs. Mosquitoes need water to lay their eggs in, so they are often found in wet or damp locations and around plants. Different species prefer different habitats. It is possible to be bitten by a mosquito at any time of the day, and again timing depends upon the species. Many are particularly active from just before dusk, through the night, and until dawn. Mosquito bites are not only itchy and annoying, but they can be associated with greater health risks. Certain mosquitoes vector pathogens that cause diseases such as West Nile virus (WNV) and eastern equine encephalitis (EEE).

For more information about mosquitoes in Massachusetts, visit: https://www.mass.gov/service-details/mosquitoes-in-massachusetts

There are ways to protect yourself against mosquitoes, including wearing long-sleeved shirts and long pants, keeping mosquitoes outside by using tight-fitting window and door screens, and using insect repellents as directed. Products containing the active ingredients DEET, permethrin, IR3535, picaridin, and oil of lemon eucalyptus provide protection against mosquitoes.

For more information about mosquito repellents, visit: https://www.mass.gov/service-details/mosquitoes-in-massachusetts and https://www.cdc.gov/features/stopmosquitoes .

- Deer Tick/Blacklegged Tick: Check out the archived FREE TickTalk with TickReport webinars available here:https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/ticktalk-with-tickreport-webinars. Previous webinars including information about deer ticks and associated diseases, ticks and personal protection, and updates from the Laboratory of Medical Zoology are archived at the link above.

The next live webinar will be held on October 14, 2020 - Tick-borne Disease Surveillance in the US- Speaker: Dr. Ben Beard, Deputy Director, Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Dr. Rich welcomes Dr. Ben Beard to the TickTalk webinar. Dr. Beard will present the latest CDC findings on the burdens of tick-borne disease and public health trends. To register for the next TickTalk, visit:https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/ticktalk-with-tickreport-webinars

Ixodes scapularis larvae (immatures) are active, and may be encountered at this time, through September. From October until roughly May, as long as daytime temperatures remain above freezing, adult male and female deer ticks can be active, even in the winter. It is important to protect yourself against ticks and be especially vigilant for tiny, difficult to see nymphs. For images of all deer tick life stages, along with an outline of the diseases they carry, visit: http://www.tickencounter.org/tick_identification/deer_tick .

Anyone working in the yard and garden should be aware that there is the potential to encounter deer ticks. The deer tick or blacklegged tick can transmit Lyme disease, human babesiosis, human anaplasmosis, and other diseases. Preventative activities, such as daily tick checks, wearing appropriate clothing, and permethrin treatments for clothing (according to label instructions) can aid in reducing the risk that a tick will become attached to your body. If a tick cannot attach and feed, it will not transmit disease. For more information about personal protective measures, visit: http://www.tickencounter.org/prevention/protect_yourself .

Have you just removed an attached tick from yourself or a loved one with a pair of tweezers? If so, consider sending the tick to the UMass Laboratory of Medical Zoology to be tested for disease causing pathogens. To submit a tick to be tested, visit: https://www.tickreport.com/ and click on the blue “Order a TickReport” button. Results are typically available within 3 business days, or less. By the time you make an appointment with your physician following the tick attachment, you may have the results back from TickReport to bring to your physician to aid in a conversation about risk.

The UMass Laboratory of Medical Zoology does not give medical advice, nor are the results of their tests diagnostic of human disease. Transmission of a pathogen from the tick to you is dependent upon how long the tick had been feeding, and each pathogen has its own transmission time. TickReport is an excellent measure of exposure risk for the tick (or ticks) that you send in to be tested. Feel free to print out and share your TickReport with your healthcare provider.

- Wasps/Hornets: As frost arrives, annual wasp and hornet nests will cease in their activity and only fertilized females will overwinter in sheltered places.

Woody ornamental insect and non-insect arthropod pests to consider, a selected few:

Spotted Lanternfly: (Lycorma delicatula, SLF) is not known to occur in Massachusetts landscapes (no established populations are known in MA at this time). However, due to the great ability of this insect to hitchhike using human-aided movement, it is important that we remain vigilant in Massachusetts and report any suspicious findings. Spotted lanternfly reports can be sent here:https://massnrc.org/pests/slfreport.aspx

Spotted Lanternfly: (Lycorma delicatula, SLF) is not known to occur in Massachusetts landscapes (no established populations are known in MA at this time). However, due to the great ability of this insect to hitchhike using human-aided movement, it is important that we remain vigilant in Massachusetts and report any suspicious findings. Spotted lanternfly reports can be sent here:https://massnrc.org/pests/slfreport.aspx

For a map of known, established populations of SLF as well as detections outside of these areas where individual finds of spotted lanternfly have occurred (but no infestations are present), visit: https://nysipm.cornell.edu/environment/invasive-species-exotic-pests/spotted-lanternfly/ This map depicts an individual detection of spotted lanternfly at a private residence in Boston, MA that was reported by the MA Department of Agricultural Resources on February 21, 2019. More information about this detection in Boston, where no established infestation was found, is provided here: https://www.mass.gov/news/state-agricultural-officials-urge-residents-to-check-plants-for-spotted-lanternfly

This insect is a member of the Order Hemiptera (true bugs, cicadas, hoppers, aphids, and others) and the Family Fulgoridae, also known as planthoppers. The spotted lanternfly is a non-native species first detected in the United States in Berks County, Pennsylvania and confirmed on September 22, 2014.

The spotted lanternfly is considered native to China, India, and Vietnam. It has been introduced as a non-native insect to South Korea and Japan, prior to its detection in the United States. In South Korea, it is considered invasive and a pest of grapes and peaches. The spotted lanternfly has been reported feeding on over 103 species of plants, according to new research (Barringer and Ciafré, 2020) and when including not only plants on which the insect feeds, but those that it will lay egg masses on, this number rises to 172. This includes, but is not limited to, the following: tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) (preferred host), apple (Malus spp.), plum, cherry, peach, apricot (Prunus spp.), grape (Vitis spp.), pine (Pinus spp.), pignut hickory (Carya glabra), Sassafras (Sassafras albidum), serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.), slippery elm (Ulmus rubra), tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera), white ash (Fraxinus americana), willow (Salix spp.), American beech (Fagus grandifolia), American linden (Tilia americana), American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis), big-toothed aspen (Populus grandidentata), black birch (Betula lenta), black cherry (Prunus serotina), black gum (Nyssa sylvatica), black walnut (Juglans nigra), dogwood (Cornus spp.), Japanese snowbell (Styrax japonicus), maple (Acer spp.), oak (Quercus spp.), and paper birch (Betula papyrifera).

The adults and immatures of this species damage host plants by feeding on sap from stems, leaves, and the trunks of trees. In the springtime in Pennsylvania (late April - mid-May) nymphs (immatures) are found on smaller plants and vines and new growth of trees and shrubs. Third and fourth instar nymphs migrate to the tree of heaven and are observed feeding on trunks and branches. Trees may be found with sap weeping from the wounds caused by the insect’s feeding. The sugary secretions (excrement) created by this insect may coat the host plant, later leading to the growth of sooty mold. Insects such as wasps, hornets, bees, and ants may also be attracted to the sugary waste created by the lanternflies, or sap weeping from open wounds in the host plant. Host plants have been described as giving off a fermented odor when this insect is present.

Adults are present by the middle of July in Pennsylvania and begin laying eggs by late September and continue laying eggs through late November and even early December in that state. Adults may be found on the trunks of trees such as the tree of heaven or other host plants growing in close proximity to them. Egg masses of this insect are gray in color and look similar in some ways to gypsy moth egg masses.

Host plants, bricks, stone, lawn furniture, recreational vehicles, and other smooth surfaces can be inspected for egg masses. Egg masses laid on outdoor residential items such as those listed above may pose the greatest threat for spreading this insect via human aided movement.

For more information about the spotted lanternfly, visit this fact sheet: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/spotted-lanternfly .

Asian Longhorned Beetle: (Anoplophora glabripennis, ALB) is a serious invasive insect that was first detected in Massachusetts in August of 2008. ALB was detected for the first time in South Carolina in 2020. Asian longhorned beetle eradication programs currently exist in Massachusetts, New York, and Ohio. A homeowner is responsible for finding, reporting, and making officials aware of the infestation in South Carolina. Great job!

Asian Longhorned Beetle: (Anoplophora glabripennis, ALB) is a serious invasive insect that was first detected in Massachusetts in August of 2008. ALB was detected for the first time in South Carolina in 2020. Asian longhorned beetle eradication programs currently exist in Massachusetts, New York, and Ohio. A homeowner is responsible for finding, reporting, and making officials aware of the infestation in South Carolina. Great job!

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) and the Clemson University’s Department of Plant Industry (DPI) are inspecting trees in Hollywood, South Carolina following the detection and identification of the Asian longhorned beetle (ALB).

On May 29, a homeowner in Hollywood, South Carolina contacted DPI to report they found a dead beetle on their property and suspected it was ALB. A DPI employee collected the insect the same day and conducted a preliminary survey of the trees on the property. Clemson’s Plant and Pest Diagnostic Clinic provided an initial identification of ALB, and on June 4, APHIS’ National Identification Services confirmed the insect. On June 11, APHIS and DPI inspectors confirmed that one tree on the property is infested, and a second infested tree was found on an adjacent property. For more information, visit: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/newsroom/stakeholder-info/sa_by_date/sa-2020/sa-06/alb-sc . A recently released “Draft Environmental Assessment for the Asian Longhorned Beetle Eradication Program in Charleston, Dorchester, and Colleton Counties in South Carolina” from the USDA-APHIS provides a map of the currently known infested trees in that location. For more information, visit:https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/newsroom/federal-register-posts/sa_by_date/sa-2020/alb-draft-ea .

This is a good reminder for us to remain vigilant, and report any suspicious beetles or damage to trees, especially maples. Asian longhorned beetle infests 12 genera of trees, however maples are preferred hosts.

Look for signs of an ALB infestation which include perfectly round exit holes (about the size of a dime), shallow oval or round scars in the bark where a female has chewed an egg site, or sawdust-like frass (excrement) on the ground nearby host trees or caught in between branches. Be advised that other, native insects may create perfectly round exit holes or sawdust-like frass, which can be confused with signs of ALB activity.

The regulated area for Asian longhorned beetle is 110 miles2 encompassing Worcester, Shrewsbury, Boylston, West Boylston, and parts of Holden and Auburn. If you believe you have seen damage caused by this insect, such as exit holes or egg sites, on susceptible host trees like maple, please call the Asian Longhorned Beetle Eradication Program office in Worcester, MA at 508-852-8090 or toll free at 1-866-702-9938.

To report an Asian longhorned beetle find online or compare it to common insect look-alikes, visit: http://massnrc.org/pests/albreport.aspx or https://www.aphis.usda.gov/pests-diseases/alb/report .

More information can be found in the “Trouble Maker of the Month” section of July’s edition of Hort Notes:https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/newsletters/hort-notes/hort-notes-2020-vol-315

- Azalea Sawflies: One species of azalea sawfly, Arge clavicornis, is found as an adult in July and lays its eggs in leaf edges in rows. Larvae are present in August and September. Remember, sawfly caterpillars have at least enough abdominal prolegs to spell “sawfly” (so 6 or more prolegs). Bacillus thuringiensis Kurstaki does not manage sawflies.

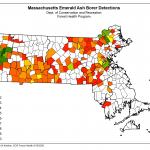

Emerald Ash Borer: (Agrilus planipennis, EAB) As of September 18, 2020, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation has confirmed a total of at least 139 communities in Massachusetts that have known populations of emerald ash borer, 40 of which have been found in 2020. An updated map of these locations across the state may be found here:https://ag.umass.edu/fact-sheets/emerald-ash-borer .

Emerald Ash Borer: (Agrilus planipennis, EAB) As of September 18, 2020, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation has confirmed a total of at least 139 communities in Massachusetts that have known populations of emerald ash borer, 40 of which have been found in 2020. An updated map of these locations across the state may be found here:https://ag.umass.edu/fact-sheets/emerald-ash-borer .

This wood-boring beetle readily attacks ash (Fraxinus spp.) including white, green, and black ash and has also been found developing in white fringe tree (Chionanthus virginicus) and has been reported in cultivated olive (Olea europaea). Adult insects of this species will not be present at this time of year. Signs of an EAB infested tree may include (at this time) D-shaped exit holes in the bark (from adult emergence in previous years), “blonding” or lighter coloration of the ash bark from woodpecker feeding (chipping away of the bark as they search for larvae beneath), and serpentine galleries visible through splits in the bark, from larval feeding beneath. Positive identification of an EAB-infested tree may not be possible with these signs individually on their own.

For further information about this insect, please visit: https://ag.umass.edu/fact-sheets/emerald-ash-borer . If you believe you have located EAB-infested ash trees, particularly in an area of Massachusetts not identified on the map provided, please report here: http://massnrc.org/pests/pestreports.htm .

- Fall Home-Invading Insects: Various insects, such as ladybugs, boxelder bugs, seedbugs, and stink bugs will begin to seek overwintering shelters in warm places, such as homes, throughout the next couple of months. While such invaders do not cause any measurable structural damage, they can become a nuisance especially when they are present in large numbers. While the invasion has not yet begun, if you are not willing to share your home with such insects, now should be the time to repair torn window screens, repair gaps around windows and doors, and shore up any other gaps through which they might enter the home.

- Hickory Tussock Moth: Lophocampa caryae is native to southern Canada and the northeastern United States. There is one generation per year. Overwintering occurs as a pupa inside a fuzzy, oval shaped cocoon. Adult moths emerge approximately in May and their presence can continue into July. Females will lay clusters of 100+ eggs together on the underside of leaves. Females of this species can fly, however they have been called weak fliers due to their large size. When first hatched from their eggs, the young caterpillars will feed gregariously in a group, eventually dispersing and heading out on their own to forage. Caterpillar maturity can take up to three months and color changes occur during this time. These caterpillars are essentially white with some black markings and a black head capsule. They are very hairy, and should not be handled with bare hands as many people can have skin irritation or rashes (dermatitis) as a result of interacting with hickory tussock moth hairs. By late September, the caterpillars will create their oval, fuzzy cocoons hidden in the leaf litter where they will again overwinter. Hosts whose leaves are fed upon by these caterpillars include but are not limited to hickory, walnut, butternut, linden, apple, basswood, birch, elm, black locust, and aspen. Maple and oak have also been reportedly fed upon by this insect. Several wasp species are parasitoids of hickory tussock moth caterpillars. Other species of tussock moth exist, and may be encountered. For a summary of some of their late-summer appearing caterpillars, visit:https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/newsletters/hort-notes/hort-notes-2020-vol-317 under “Trouble Maker of the Month”.

- Lacebugs: Stephanitis spp. lacebugs such as S. pyriodes can cause severe injury to azalea foliage. S. rhododendri can be common on Rhododendron and mountain laurel. S. takeyai has been found developing on Japanese Andromeda, Leucothoe, styrax, and willow. Stephanitis spp.lace bug activity should be monitored through September. Before populations become too large, treat with a summer rate horticultural oil spray as needed. Be sure to target the undersides of the foliage in order to get proper coverage of the insects. Certain azalea and Andromeda cultivars may be less preferred by lace bugs.

Magnolia and Tuliptree Scales: The soft scale insects known as the Magnolia scale (Neolecanium cornuparvum) and the tuliptree scale (Toumeyella liriodendri) can be difficult to differentiate in the field, depending upon the host they are found on. (On Magnolia, it is very difficult to distinguish between the two species of soft scale.) As two native scale insects in North America, the Magnolia and tuliptree scales are hosts themselves for natural enemies that can impact their populations. Solitary parasitoid larvae have been collected from Magnolia scales and have been identified as a syrphid fly species, Ocyptamus costatus. The natural enemies of the tuliptree scale have been studied to a greater degree and include certain lady beetle species [Hyperaspis signata, Adalia (formerly Hyperaspis) bipunctata, and Chilocorus stigma] which feed on nymphal scales, a number of parasitic wasps, and even an insect feeding moth caterpillar (Laetilia coccidivora). This particular moth species, also referred to as a type of snout moth, will consume the tuliptree scale underneath the protection of a silken web it spins over them! (The specific epithet coccidivora can be translated as “ones that eat soft scales” or Coccidae.) Unfortunately, in a landscape setting, it often seems that although these natural enemies may be common within the scale populations, they are seldom able to reduce the scale insect numbers below damaging levels. That being said, our management options should still seek to preserve these natural enemies.

Magnolia and Tuliptree Scales: The soft scale insects known as the Magnolia scale (Neolecanium cornuparvum) and the tuliptree scale (Toumeyella liriodendri) can be difficult to differentiate in the field, depending upon the host they are found on. (On Magnolia, it is very difficult to distinguish between the two species of soft scale.) As two native scale insects in North America, the Magnolia and tuliptree scales are hosts themselves for natural enemies that can impact their populations. Solitary parasitoid larvae have been collected from Magnolia scales and have been identified as a syrphid fly species, Ocyptamus costatus. The natural enemies of the tuliptree scale have been studied to a greater degree and include certain lady beetle species [Hyperaspis signata, Adalia (formerly Hyperaspis) bipunctata, and Chilocorus stigma] which feed on nymphal scales, a number of parasitic wasps, and even an insect feeding moth caterpillar (Laetilia coccidivora). This particular moth species, also referred to as a type of snout moth, will consume the tuliptree scale underneath the protection of a silken web it spins over them! (The specific epithet coccidivora can be translated as “ones that eat soft scales” or Coccidae.) Unfortunately, in a landscape setting, it often seems that although these natural enemies may be common within the scale populations, they are seldom able to reduce the scale insect numbers below damaging levels. That being said, our management options should still seek to preserve these natural enemies.

The Magnolia scale is distributed throughout the eastern United States. The tuliptree scale is found east of the Mississippi River from Michigan to Alabama and from New York and Connecticut to Florida. It is also reported to be found in ornamental tuliptrees and Magnolias in California and could be found wherever these trees are grown. Magnolia scale host plants include: Magnolia stellata (star Magnolia), M. acuminata (cucumber Magnolia), M. lilliflora ‘Nigra’ (lily Magnolia; formerly M. quinquepeta), and M. soulangeana (Chinese Magnolia). Other species may be hosts for this scale, but attacked to a lesser degree. M. grandiflora (southern Magnolia) may be such an example. Tuliptree scale host plants include: Liriodendron tulipifera (tuliptree or yellow poplar), Magnolia stellata (star Magnolia), and M. soulangeana (Chinese Magnolia). This insect has also been recorded on M. grandiflora (southern Magnolia) and Tilia spp. (linden). The tuliptree scale has also, to a lesser extent, been reported on other ornamental trees and shrubs.

Mature individuals settle on a location on branches and twigs, then insert piercing-sucking mouthparts to feed. The insects feed on plant fluids and excrete large amounts of a sugary substance known as honeydew. Sooty mold, often black in color, will then grow on the honeydew that has coated branches and leaves. Repeated, heavy infestations can result in branch dieback and at times, death of the plant. Honeydew may also be very attractive to ants, wasps, and hornets. The life cycle of both of these species is similar and may have similar timing during the year, however subtle differences exist. The life cycle of the Magnolia scale is as follows: This scale overwinters as a young nymph (immature stage) which is elliptical in shape, mostly a dark-slate gray, except for a median ridge that is red/brown in color. These overwintering nymphs may be found on the undersides of 1st and 2nd year old twigs. The first molt (shedding of the exoskeleton to allow growth) can occur by late April or May in parts of this insect’s range and the second molt will occur in early June. At that time, the immature scales have turned a deep purple color. Stems of the host plant may appear purple in color and thickened – but this is a coating of nymphal Magnolia scales, not the stem itself. Eventually, these immature scales secrete a white layer of wax over their bodies, looking as if they have been rolled in powdered sugar. By August, the adult female scale is fully developed, elliptical and convex in shape and ranging from a pinkish-orange to a dark brown color. Adult females may also be covered in a white, waxy coating. By that time, the females produce nymphs (living young; eggs are not “laid”) that wander the host before settling on the newest twigs to overwinter. In the Northeastern United States, this scale insect has a single generation per year.

The lifecycle of the tuliptree scale is as follows: The mature female tuliptree scale is hemispherical in shape. The color of the mature female varies in this species as well - a grayish-green to pink-orange insect mottled with black. Adult males emerge sometime in June and mate with the females. Like the Magnolia scale, eggs develop within the body of the female tuliptree scale, leading to the “live birth” of immatures (crawlers) in late August and September. In the Northeast, one generation of tuliptree scales occurs per year. (However, in the southern-most portions of its range, this insect has been found in all stages of development during the winter, suggesting multiple generations per year.) A single female tuliptree scale may produce 3,000+ crawlers in one season. These crawlers are tiny (approximately the size of the head of a pin) and settle on host plant twigs in September. Past studies have shown that in addition to moving on their own with fully functional legs, the crawlers can be blown to new hosts on the wind, up to 100 feet away. (Being wind-blown to a new host, however, is a haphazard method of travel through which less than 20% of these crawlers successfully make contact with a host plant, and fewer still attach to a suitable site on the plant.) The immature, crawler stage molts once prior to overwintering.

Concerned that you may have found an invasive insect or suspicious damage caused by one? Need to report a pest sighting? If so, please visit the Massachusetts Introduced Pests Outreach Project: http://massnrc.org/pests/pestreports.htm .

A note about Tick Awareness: deer ticks (Ixodes scapularis), the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), and the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) are all found throughout Massachusetts. Each can carry their own complement of diseases. Anyone working in tick habitats (wood-line areas, forested areas, and landscaped areas with ground cover) should check themselves regularly for ticks while practicing preventative measures. Have a tick and need it tested? Visit the web page of the UMass Laboratory of Medical Zoology (https://www.tickreport.com/ ) and click on the blue Order a TickReport button for more information.

Reported by Tawny Simisky, Extension Entomologist, UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, & Urban Forestry Program

Weeds

Japanese knotweed in Massachusetts is in full flower to early petal drop, so now continues to be a great time to manage this invasive plant. Use 2% spray solution of glyphosate products (4 pounds per U.S. gallon of the active ingredient) sprayed to the initiation of spray drip. [The formulation, such as in Roundup Pro, is a 4 lb per gallon formulation, meaning it has 4 lbs of glyphosate active ingredient in a gallon of product. You are making a 2 % solution. Since there are 128 ounces in a gallon, a 1% solution would be 1.28 ounces and a 2% solution would be 2.56 ounces per gallon of water for a spray solution.] Do not use herbicide formulations that contain diquat (RewardTM) or tank-mix pelargonic acid (ScytheTM) with the glyphosate, since diquat and pelargonic acid are contact herbicides and have the potential to decrease the efficacy of glyphosate. In areas near water, a formulation of glyphosate that is labeled for these areas should be used. Non-chemical products containing clove oil, citric acid, acetic acid, or orange extract will not effectively control Japanese knotweed.

Poison ivy can be treated during the month of September. Glyphosate or triclopyr are the best herbicides for poison ivy control. Triclopyr products should be selected over glyphosate products in areas were grasses need to be saved. Contact (ScytheTM, RewardTM) or the non-chemical/organic herbicide products will provide “burndown” activity only and will not adequately control poison ivy.

Report by Randy Prostak, Weed Specialist, UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery and Urban Forestry Program

Landscape Practices

With practically all of Massachusetts in "Severe Drought", "Moderate Drought" or "Abnormally Dry" as of 9/1/20, according to the US Drought Monitor (https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?MA), it is important to irrigate as efficiently as possible. The following tips will help ensure that irrigation applications are as beneficial as possible.

1. Be aware of, and follow, your local town or municipality water regulations. https://www.mass.gov/doc/water-use-restrictions-map/download

2. Don’t irrigate midday. Evaporation is greatest midday, which could mean that much of the water being applied is lost before it reaches plants! Wind also contributes to evaporation and can change irrigation spray patterns. Early morning and evening are the best times to irrigate.

3. Use drip irrigation or soaker hoses when possible. Overhead irrigation frequently results in watering non-plant surfaces and can result in water interception by plant canopies which can reduce the water that reaches the plants’ root systems.

4. Maintain your irrigation system. Check for leaks, broken spray heads, and perform an irrigation system audit to assure uniformity.

5. Use smart technology. Smart controllers can monitor soil moisture and use environmental conditions to adjust irrigation based on water being lost to evapotranspiration (evaporation and transpiration).

6. Water deeply, allowing water to soak into the ground. Irrigating slowly (via drip irrigation or a slow flow) is key to achieving infiltration vs. runoff. Newly installed plants will need more frequent irrigation until established, especially container grown plants that were produced in soilless substrates. Less frequent, deeper irrigation encourages good root growth which will help plants survive water stress.

7. Apply mulch to planting beds and in tree rings 2-4” deep. Keep mulch away from the base of plants and trees. Mulch helps reduce evaporation, insulates plant roots, and can add organic matter to the soil.

8. Raise your mower blade. Longer grass promotes deeper roots and a more drought-resistant lawn.

9. Reduce the competition for water by controlling weeds.

10. Don’t apply fertilizer under drought conditions. High fertilizer concentration can make available water unavailable to plants. Fertilization will also result in increased growth which increases the water demand.

11. Keep in mind that landscapes typically require one inch of water per week (including rainfall). Unsure of what your system or sprinkler is applying? You can use a rain gauge and see how much water is collected in a certain period of time (30 minutes for example). Use multiple rain gauges if possible to understand if you have good uniformity, or make sure the rain gauge is located in an “average area”.

Report by Mandy Bayer, Extension Assistant Professor of Sustainable Landscape Horticulture, UMass Stockbridge School of Agriculture

Additional Resources

Pesticide License Exams - The MA Dept. of Agricultural Resources (MDAR) is holding exams for new exam applicants. Space is still limited; to register, go to: https://www.mass.gov/pesticide-examination-and-licensing.

To receive immediate notification when the next Landscape Message update is posted, join our e-mail list or follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

For a complete listing of upcoming events, see our upcoming educational events https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/upcoming-events

For commercial growers of greenhouse crops and flowers - Check out UMass Extension's Greenhouse Update website

For professional turf managers - Check out Turf Management Updates

For home gardeners and garden retailers - Check out our home lawn and garden resources. UMass Extension also has a Twitter feed that provides timely, daily gardening tips, sunrise and sunset times to home gardeners at twitter.com/UMassGardenClip

Diagnostic Services

The UMass Plant Diagnostic Lab and the Soil & Plant Nutrient Testing Lab are open and taking samples (mail-in only please, walk-in samples cannot be accepted). Allow additional turnaround time as mail delivery and staffing have been altered due to the pandemic.

- Plant disease, insect pest and invasive plant/weed samples: go to https://ag.umass.edu/services/plant-diagnostics-laboratory for more details.

- Routine soil analysis and particle size analysis ONLY (no other types of analyses available at this time): go to https://ag.umass.edu/services/soil-plant-nutrient-testing-laboratory.

UMass Laboratory Diagnoses Landscape and Turf Problems - The UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab is available to serve commercial landscape contractors, turf managers, arborists, nurseries and other green industry professionals. It provides woody plant and turf disease analysis, woody plant and turf insect identification, turfgrass identification, weed identification, and offers a report of pest management strategies that are research based, economically sound and environmentally appropriate for the situation. Accurate diagnosis for a turf or landscape problem can often eliminate or reduce the need for pesticide use. For sampling procedures, detailed submission instructions and a list of fees, see Plant Diagnostic Laboratory

Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing - The University of Massachusetts Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory is located on the campus of The University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Testing services are available to all. The function of the Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory is to provide test results and recommendations that lead to the wise and economical use of soils and soil amendments. For complete information, visit the UMass Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory web site. Alternatively, call the lab at (413) 545-2311.

Ticks are active any time that temperatures are above freezing! Remember to take appropriate precautions when working and playing outdoors, and conduct daily tick checks. UMass tests ticks for the presence of Lyme disease and other disease pathogens. Learn more