Solanaceous, Bacterial Canker

Clavibacter michiganensis pv. michiganensis

Bacterial canker (Clavibacter michiganensis pv. michiganensis) (Cmm) is one of the most destructive tomato diseases in Massachusetts. It can also occur on pepper, but is only economically important on tomato. This disease occurs worldwide and although its occurrence is sporadic, it can cause devestating losses. Bacterial canker is especially severe on transplanted or direct-seeded tomatoes that have been clipped or pruned. When infested seed is used for transplant production, those transplants will develop systemic infections and may wilt and die, fail to set fruit, or may show no symptoms at all. Warm, humid conditions in the greenhouse are extremely conducive to disease development and spread. Often, plants infected in this manner do not show symptoms until they have been planted in the field or greenhouse and have begun to flower.

Identification:

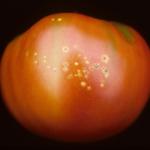

Initial symptoms are the result of primary, systemic infection and first affect the lower leaves causing leaf curling, wilting, chlorosis, and shriveling. Plants infected from seed may die, fail to set fruit, or show no symptoms. In advanced stages, the pathogen spreads throughout the plant and causes poor growth, wilt, and plant death. Foliage throughout the canopy wilts, yellows, turns brown, and collapses. Stems can split resulting in open breaks or cankers and stems break easily. Secondary infections occur from rain splash onto foliage, stems, and fruit. Spots occur on green fruit and are very characteristic: white to yellow spots, 3-4 mm with raised brown centers (“bird’s eye spots”). If infected plants are present, the movement of bacteria from one plant to another during normal watering, handling, and ventilating activities occurs readily.

Primary, systemic infections may not cause symptoms until the plants begin to flower. Plants begin to wilt starting from the lower leaves and progressing upward. Early symptoms include one-sided wilting of leaves, and downward cupping of leaves. Later, stems may develop adventitious roots, external brown streaks, or may split open revealing internal discoloration of vascular tissue. The discoloration is yellowish to brown at first but becomes dark reddish brown and eventually the stem pith also becomes discolored and rotten.

Marginal scorch or “firing” occurs when bacteria on the leaf surface enter leaves via guttation droplets that form at night on the leaf’s edge. Guttation droplets form when there is high soil moisture and no transpiration occurring - as on cool, moist, summer nights. Under these conditions, water is forced out of the hydathodes and is then sucked back into the plant when transpiration begins again after the sun comes out. In this way, bacterial cells can actually be sucked into the leaf and cause the classic leaf scorch or “firing” associated with bacterial canker. Superficial infections also cause spots on leaves and fruit. In the greenhouse, small, white, blister-like spots surrounded by dark rings form on leaves of young plants.

Life Cycle:

Sources of inoculum for this disease include seed, infected plant debris, weed hosts, volunteer plants, and contaminated stakes. The bacterium is known to persist on the surface of seeds as well as within the seed coat. Bacteria survive in the field as long as there is any infected crop debris. They persist longer in debris on the surface than in buried debris. The bacterium also survives in crop residues in the field which can persist for 2-3 years. During the rotation out of tomatoes, it is imperative to control Solanaceous weeds in order to prevent the pathogen from surviving in the field. The bacterium has been shown to survive on wooden stakes and spread through clean fields from there.

Cmm spreads in two ways, systemically through the plant vascular system and superficially, on leaf or fruit surfaces. When an infested seed is planted, a primary, systemic infection results, and the bacteria move up from the infested seed through the plant vasculature. Secondary systemic infections may occur when a plant is wounded at a branch tip, as when clipping apical buds, and the pathogen gets into the plant and moves rapidly downward toward the base, killing the plant. The bacterium also successfully colonizes the external plant tissue and can cause superficial infections on leaves, stems, and fruits. This superficial, secondary spread is quite common and is responsible for the rapid spread of disease and for some of the most characteristic symptoms. Secondary spread is primarily by splashing water, rain, forceful sprays, contaminated equipment (trays, pots, stakes etc.), workers handling plants or pruning/cutting.

Cultural Controls & Prevention:

Prevention is cost-effective. All of these tactics focus on prevention -- ensuring that disease-free plants go out into a “clean” environment. Bacterial canker outbreaks in the field require regular sprays with a copper or copper/maneb mix, with limited success. Prevention strategies are both the least expensive and the most effective way to control bacterial canker.

- Start with certified, disease-free seed or treat seed with hot water, hydrochloric acid, calcium hypochlorite, or other recommended materials. The bacterial canker pathogen can be seed-borne, both on the surface of the seed and under the seed coat.

- Control bacterial populations that may be present on the leaf surface of transplants in the greenhouse. Young transplants may not display symptoms of bacterial diseases. Inspect and remove suspect transplants. Lower the water pressure in irrigation equipment to avoid damaging leaves. Avoid the practice of mowing transplants to regulate transplant height.

- Plant into a clean field. Promptly incorporate crop debris after harvest. Rotate to a non-host crop before returning to tomato and do not allow volunteer tomato or weed hosts to survive. Bacterial canker survives in the field as long as there is any infected crop debris. It lasts longer in debris on the surface than it does in buried debris. Plowing after harvest will help to speed up the decomposition.

- Avoid working in fields when bacterial diseases are present and the fields are wet.

- Rotate tomatoes (and related crops such as potato and eggplant) for 2-3 years to a different field. Setting clean transplants into a field where canker-infected tomato was grown the previous year will result in early infection with canker and reduced yields.

- New fields should, as much as is possible, be located at a distance from last year’s fields -- as far as possible given the choices available on your farm.

- Bacteria on the surface of transplants can be effectively controlled by sprays of copper hydroxide or streptomycin in the greenhouse. Kocide DF, Agri-Strep and Agri-mycin 17, and Dithane F-45 are labeled for greenhouse use on tomato.

- Using bactericide in the greenhouse means a lower volume of chemical is used compared to multiple copper sprays in the field. Check the label carefully for required REI and personal protective equipment.

Chemical Controls & Pesticides:

For Current information on disease recommendations ins specific crops including information on chemical control & pesticide management, please visit the New England Vegetable Management Guide website.

Crops that are affected by this disease:

The Center for Agriculture, Food and the Environment and UMass Extension are equal opportunity providers and employers, United States Department of Agriculture cooperating. Contact your local Extension office for information on disability accommodations. Contact the State Center Director’s Office if you have concerns related to discrimination, 413-545-4800 or see ag.umass.edu/civil-rights-information.