To print this issue, either press CTRL/CMD + P or right click on the page and choose Print from the pop-up menu.

Click on images to enlarge.

Crop Conditions

It’s peak tomato season! While the plants are starting to accumulate legions of spots and wilts, the fruit is still coming on strong and steady, and crews are spending long mornings harvesting, polishing, and sorting the bounty. Congratulations to all those who participated in the MA Tomato Contest and to this year’s winners, including the 1st place Speckled Roman grown by Russell Orchards in Ipswich, MA, and the heaviest tomato, a 2.3 lb Oxheart tomato, grown by Ward’s Berry Farm in Sharon, MA. Peppers are ripening in all their brightly colored glory, reminding us that summer is not yet over, even though nighttime temperatures are getting down to 50°F! Fall is certainly right around the corner now; winter squash season has officially begun and the first bins of spaghetti squash and butternut are rolling in. Many farms are preparing for a big shift as high school and college student workers go back to school, making big jobs, like squash and sweet potato harvests, harder to pull off.

It’s peak tomato season! While the plants are starting to accumulate legions of spots and wilts, the fruit is still coming on strong and steady, and crews are spending long mornings harvesting, polishing, and sorting the bounty. Congratulations to all those who participated in the MA Tomato Contest and to this year’s winners, including the 1st place Speckled Roman grown by Russell Orchards in Ipswich, MA, and the heaviest tomato, a 2.3 lb Oxheart tomato, grown by Ward’s Berry Farm in Sharon, MA. Peppers are ripening in all their brightly colored glory, reminding us that summer is not yet over, even though nighttime temperatures are getting down to 50°F! Fall is certainly right around the corner now; winter squash season has officially begun and the first bins of spaghetti squash and butternut are rolling in. Many farms are preparing for a big shift as high school and college student workers go back to school, making big jobs, like squash and sweet potato harvests, harder to pull off.

Alliums

Allium leafminer: As we near the start of September, leek growers should start planning their allium leafminer (ALM) management tactics ahead of the fall flight. Adult ALM flies will emerge from the soil in early to mid-September and lay eggs in any allium crops still in the field (primarily leeks). If you’re sure that your field does not have a history of ALM, you can cover leek crops with row cover to exclude the flies during the flight. Otherwise, plan to protect your crop with insecticides. The most effective conventional materials are dinotefuran (e.g. Scorpion 35 SL, 7 fl oz/A), cyantraniliprole (e.g. Exirel, 13.5 fl oz/A), spinetoram (e.g. Radiant, 8 fl oz/A), and lambda-cyhalothrin (e.g. Warrior II, 8 fl oz/A). If you have been spraying for thrips all season long, make sure you haven’t already reached the max annual application rate of Radiant and/or Exirel. The most effective OMRI-listed materials are spinosad (e.g. Entrust, 6 oz/A) + M-Pede at the 1-1.5% v/v solution rate. Apply this mixture 2 times, 2-4 weeks after ALM emergence is first detected.

Brassicas

Brassica downy mildew was observed in broccoli transplants this week in Hampshire Co. This is a different species than the downy mildews that cause disease in basil, cucurbits, alliums, or lettuce. The pathogen causes irregular yellow lesions with dark veins on the top sides of brassica leaves. The undersides of the lesions develop a crusty white sporulation. In transplants, infected cotyledons will become chlorotic and drop. The pathogen can originate from brassica weeds and may be carried on seeds. During the season, infective sporangia are spread between farms and fields by wind and splashing water. Downy mildew can be controlled using fungicides, if applied early (before or as soon as symptoms develop) and often. See the cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, and other brassica crops disease control section of the New England Vegetable Management Guide for labeled materials. Note: many materials are not allowed for use on transplants. Check labels before use. If a label is silent about greenhouse/transplant use, it is legal to use it on transplants.

Brassica downy mildew was observed in broccoli transplants this week in Hampshire Co. This is a different species than the downy mildews that cause disease in basil, cucurbits, alliums, or lettuce. The pathogen causes irregular yellow lesions with dark veins on the top sides of brassica leaves. The undersides of the lesions develop a crusty white sporulation. In transplants, infected cotyledons will become chlorotic and drop. The pathogen can originate from brassica weeds and may be carried on seeds. During the season, infective sporangia are spread between farms and fields by wind and splashing water. Downy mildew can be controlled using fungicides, if applied early (before or as soon as symptoms develop) and often. See the cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, and other brassica crops disease control section of the New England Vegetable Management Guide for labeled materials. Note: many materials are not allowed for use on transplants. Check labels before use. If a label is silent about greenhouse/transplant use, it is legal to use it on transplants.

Cucurbits

Cucurbit downy mildew (CDM) was confirmed on Sunday on pumpkin in New Jersey. It is now possible that CDM will develop in any cucurbit crop in MA. Winter squash growers should now regularly apply both broad-spectrum and downy mildew-targeted fungicides to their crops. Recommended broad-spectrum materials are chlorothalonil or copper, both of which are effective against both CDM and cucurbit powdery mildew. Recommended CDM-targeted materials include Elumin, Zing!, Gavel, Orondis Opti, Zampro, Omega, Previcur Flex, and Ranman. Presidio, Revus, and Forum are NOT recommended, due to pathogen resistance. Rotate between 2 targeted materials for resistance management. There are 2 clades of CDM that affect different cucurbit crops. Clade 1 isolates preferentially infect watermelon, kabocha squash and giant pumpkin (both Cucurbita maxima), butternut squash, and summer squashes, acorn squash, and Halloween pumpkin (all Cucurbita pepo). Clade 2 isolates preferentially infect cucumber and cantaloupe. Clade 2 usually arrives in New England first and has been present in MA on both cucumber and cantaloupe since at least early August. This is the first report of Clade 1 north of Virginia this year. If you suspect CDM in any of your cucurbit crops, please let us know at umassveg@umass.edu or 413-577-3976, so we can help to track this important disease. For more information on CDM management, see Managing Cucurbit Downy and Powdery Mildew.

Cucurbit downy mildew (CDM) was confirmed on Sunday on pumpkin in New Jersey. It is now possible that CDM will develop in any cucurbit crop in MA. Winter squash growers should now regularly apply both broad-spectrum and downy mildew-targeted fungicides to their crops. Recommended broad-spectrum materials are chlorothalonil or copper, both of which are effective against both CDM and cucurbit powdery mildew. Recommended CDM-targeted materials include Elumin, Zing!, Gavel, Orondis Opti, Zampro, Omega, Previcur Flex, and Ranman. Presidio, Revus, and Forum are NOT recommended, due to pathogen resistance. Rotate between 2 targeted materials for resistance management. There are 2 clades of CDM that affect different cucurbit crops. Clade 1 isolates preferentially infect watermelon, kabocha squash and giant pumpkin (both Cucurbita maxima), butternut squash, and summer squashes, acorn squash, and Halloween pumpkin (all Cucurbita pepo). Clade 2 isolates preferentially infect cucumber and cantaloupe. Clade 2 usually arrives in New England first and has been present in MA on both cucumber and cantaloupe since at least early August. This is the first report of Clade 1 north of Virginia this year. If you suspect CDM in any of your cucurbit crops, please let us know at umassveg@umass.edu or 413-577-3976, so we can help to track this important disease. For more information on CDM management, see Managing Cucurbit Downy and Powdery Mildew.

Squash vine borer (SVB) trap counts are up slightly from last week but all sites are reporting below-threshold counts. It does look like we are seeing a second generation of adults flying now, which will lay eggs in winter squash. For growers who are trapping, if trap counts reach above 5 moths/week, an insecticide application should be made to winter squash, targeting the fruit (as opposed to the bases of the plants, which are targeted in the first generation flight).

|

table 1. Squash Vine borer Pheromone Trap captures for week ending August 22

|

|

|---|---|

|

Trap location

|

SVB

|

|

Whately

|

4 |

|

North Easton

|

2 |

|

Westhampton

|

4 |

|

Spray thresholds: Thick-stemmed cucurbits only. 5 moths/week for bush-type cucurbits. 12 moths/week for vining cucurbits.

|

|

Nightshades

Late blight was confirmed on tomato near Burlington, VT this week. It was reported in northern ME and central NY several weeks ago, so it is slowly moving closer to MA. Growers with tomato crops that are still relatively healthy and free of other diseases, who expect to get significant yields from the crop in September, should protect their crop with fungicides now, if you’re not already. Some strains of late blight are resistant to the fungicide mefenoxam (e.g. Ridomil Gold Bravo, Ridomil Gold Copper, and Ridomil Gold MZ WG). The strain present in VT has not yet been identified but the strains next-closest to us were both identified as US-23, which is sensitive to mefenoxam, meaning the Ridomil fungicides will be effective against the pathogen. Other effective fungicides include Previcur Flex and Presidio SC (both systemic); Revus Top, Forum, and Tanos (all translaminar); and Quadris Opti, Quadris Top, and Cabrio (less effective than the previous materials). Ranman, Gavel, and Zoxium, as well as chlorothalonil and mancozeb products, can be used as protectant fungicides against late blight. The most effective OMRI-listed material is copper. Please report any suspected cases of late blight in MA to us at umassveg@umass.edu or 413-577-3976.

Late blight was confirmed on tomato near Burlington, VT this week. It was reported in northern ME and central NY several weeks ago, so it is slowly moving closer to MA. Growers with tomato crops that are still relatively healthy and free of other diseases, who expect to get significant yields from the crop in September, should protect their crop with fungicides now, if you’re not already. Some strains of late blight are resistant to the fungicide mefenoxam (e.g. Ridomil Gold Bravo, Ridomil Gold Copper, and Ridomil Gold MZ WG). The strain present in VT has not yet been identified but the strains next-closest to us were both identified as US-23, which is sensitive to mefenoxam, meaning the Ridomil fungicides will be effective against the pathogen. Other effective fungicides include Previcur Flex and Presidio SC (both systemic); Revus Top, Forum, and Tanos (all translaminar); and Quadris Opti, Quadris Top, and Cabrio (less effective than the previous materials). Ranman, Gavel, and Zoxium, as well as chlorothalonil and mancozeb products, can be used as protectant fungicides against late blight. The most effective OMRI-listed material is copper. Please report any suspected cases of late blight in MA to us at umassveg@umass.edu or 413-577-3976.

Stemphylium/gray leaf spot was observed this week in high tunnel tomatoes causing severe defoliation. This is a fungal disease that causes brown leaf spots that develop a fuzzy gray sporulation. Fungicides effective against Septoria leaf spot and early blight should be effective against Stemphylium but need to be applied early and often and will not be effective once the pathogen is causing significant damage. For more information, see our Gray Leaf Spot on Tomato article.

Stemphylium/gray leaf spot was observed this week in high tunnel tomatoes causing severe defoliation. This is a fungal disease that causes brown leaf spots that develop a fuzzy gray sporulation. Fungicides effective against Septoria leaf spot and early blight should be effective against Stemphylium but need to be applied early and often and will not be effective once the pathogen is causing significant damage. For more information, see our Gray Leaf Spot on Tomato article.

Botrytis gray mold is prevalent in some high tunnel tomatoes, causing stem cankers and fruit rot as well as ghost spots on fruit. Botrytis causes lesions on leaves and stems that expand over time, often developing concentric rings that give them a target-spot appearance. Botrytis is a weak pathogen that often infects plants via pruning cuts or senescing flowers. Ghost spots on fruit are formed when Botrytis spores land on fruit and cause an infection that is then compartmentalized and stopped by the plant.

Botrytis gray mold is prevalent in some high tunnel tomatoes, causing stem cankers and fruit rot as well as ghost spots on fruit. Botrytis causes lesions on leaves and stems that expand over time, often developing concentric rings that give them a target-spot appearance. Botrytis is a weak pathogen that often infects plants via pruning cuts or senescing flowers. Ghost spots on fruit are formed when Botrytis spores land on fruit and cause an infection that is then compartmentalized and stopped by the plant.

Leaf mold was identified causing disease in outdoor tomatoes in Franklin Co. this week. This is a fungal pathogen that forms dense olive green sporulation in patches on the undersides of leaves. The corresponding tops of the leaves turn yellow. We most commonly see leaf mold in high tunnels, where humidity is very high, but under humid conditions we sometimes see it in field tomatoes. There are many excellent leaf mold-resistant varieties available, which hold up under even severe disease pressure.

Leaf mold was identified causing disease in outdoor tomatoes in Franklin Co. this week. This is a fungal pathogen that forms dense olive green sporulation in patches on the undersides of leaves. The corresponding tops of the leaves turn yellow. We most commonly see leaf mold in high tunnels, where humidity is very high, but under humid conditions we sometimes see it in field tomatoes. There are many excellent leaf mold-resistant varieties available, which hold up under even severe disease pressure.

Verticillium wilt is continuing to develop in eggplant and okra. This disease is caused by a soil-borne fungus that infects and clogs the water-conducting tissue of the plant. Leaves of infected plants wilt and become dull and pale green. Plants’ vascular tissue is organized like a bundle of tubes, and Verticillium often initially infects only some of the tubes, causing leaves to wilt on only one side of the midrib. Infected leaves also frequently develop an angular, mottled look. Verticillium has a wide host range and is difficult to manage using crop rotations. There are also no effective chemical controls (there are many biopesticides labeled for this disease but insufficient data supporting their efficacy in the field). There are no truly resistant eggplant varieties but some varieties, including Epic, Long Purple, Rosa Bianca, Casper, and Classic, may maintain high yields despite infection. Maintaining adequate soil moisture and fertility will also help to maximize plant health and yields in affected plants.

Verticillium wilt is continuing to develop in eggplant and okra. This disease is caused by a soil-borne fungus that infects and clogs the water-conducting tissue of the plant. Leaves of infected plants wilt and become dull and pale green. Plants’ vascular tissue is organized like a bundle of tubes, and Verticillium often initially infects only some of the tubes, causing leaves to wilt on only one side of the midrib. Infected leaves also frequently develop an angular, mottled look. Verticillium has a wide host range and is difficult to manage using crop rotations. There are also no effective chemical controls (there are many biopesticides labeled for this disease but insufficient data supporting their efficacy in the field). There are no truly resistant eggplant varieties but some varieties, including Epic, Long Purple, Rosa Bianca, Casper, and Classic, may maintain high yields despite infection. Maintaining adequate soil moisture and fertility will also help to maximize plant health and yields in affected plants.

Sweet corn

European corn borer (ECB) trap counts remain low and most ECB are being cleaned up by CEW sprays now.

Corn earworm (CEW) trap counts dropped in most locations, compared to last week, and caterpillar development has slowed down with the cooler weather that we've had. Most trapping sites are still on a 4-day spray schedule though, and growers should stay on top of sprays as the temperatures increase again this weekend. There are several trapping locations with low enough CEW trap counts that an insecticide application is not warranted to target CEW; in these cases, corn should be scouted for ECB and FAW larvae and an insecticide application should be made if total combined infestation is above 12%.

Fall armyworm (FAW) trap counts are up this week, and we have one report of significant damage in whorl-stage corn, with lots of FAW caterpillars in older plantings. Scout your last, whorl-stage blocks of corn for ragged feeding damage in the leaves. The most effective time to spray for FAW is as soon as the tassels have fully emerged; the FAW larvae will no longer be protected within the whorl but they will not yet have moved down the stalk and into the ear.

| Table 2. GDDs & Sweet corn pest trap captures for week ending August 22 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest Weather station |

GDD (Base 50°F) |

Trap Location | ECB NY | ECB IA | FAW | CEW | CEW SPRay interval* |

| Western MA | |||||||

| North Adams | 2100 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Richmond | 1913 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| South Deerfield | 2296 | Whately | 2 | 0 | 5 | 14.5 | 4 days |

| Chicopee Falls | 2339 | Granby | 0 | 0 | 8 | 20 | 4 days |

| Granville | 2017 | Southwick | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 days |

| Central MA | |||||||

| Leominster | 2120 | Lancaster | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | no spray** |

| Northbridge | 2150 | Grafton | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | no spray** |

| Worcester | 2145 | Spencer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | no spray** |

| Eastern MA | |||||||

| Bolton | 2165 | Bolton | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12.5 | 4 days |

| Stow | 2176 | Concord | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | no spray** |

| Lawrence | 2224 | Haverhill | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | no spray** |

| Ipswich | 2187 | Ipswich | 4 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 4 days |

| Harvard | 2160 | Littleton | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | no spray** |

| - | - | Millis | 1 | 0 | n/a | 7 | 4 days |

| Sharon | 2122 | North Easton | 1 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 4 days |

| Sharon | - | - | n/a | 49 | 4 days | ||

| Providence, RI | 2210 | Seekonk | 0 | 0 | 2 | 119 | 3 days |

| Swansea | 0 | 0 | 2 | 43 | 4 days | ||

|

ND - no GDD data for this location - no numbers reported for this trap n/a - this site does not trap for this pest * If 2+ days above 80°F occur, shorten spray interval by 1 day. ** If CEW trap captures are below 1.4 moths/week, scout block for ECB and FAW caterpillars and make a pesticide application if 12% of plants in a 50-plant sample are infested. |

|||||||

| Table 3. corn earworm spray intervals | ||

|---|---|---|

| Moths/Night | Moths/Week | Spray Interval |

| 0 - 0.2 | 0 - 1.4 | no spray |

| 0.2 - 0.5 | 1.4 - 3.5 | 6 days |

| 0.5 - 1 | 3.5 - 7 | 5 days |

| 1 - 13 | 7 - 91 | 4 days |

| Over 13 | Over 91 | 3 days |

Multiple Crops

Phytophthora blight is continuing to spread, causing fruit rot and wilt in peppers and eggplants as well as crown and fruit rot in cucurbits. Sunscald on pepper fruit can cause damage that can be confused for Phytophthora fruit rot. Sunscald will notably occur just on sides of the fruit exposed to the sun; damaged tissue will initially turn white/tan, and then is often colonized by non-pathogenic fungi that produce lots of black sporulation. Fruit infected with Phytophthora capsici will rot but remain on the plant. The foliage can sometimes remain unaffected while the fruit rots, but the plant will eventually wilt and develop dark stem cankers.

Phytophthora blight is continuing to spread, causing fruit rot and wilt in peppers and eggplants as well as crown and fruit rot in cucurbits. Sunscald on pepper fruit can cause damage that can be confused for Phytophthora fruit rot. Sunscald will notably occur just on sides of the fruit exposed to the sun; damaged tissue will initially turn white/tan, and then is often colonized by non-pathogenic fungi that produce lots of black sporulation. Fruit infected with Phytophthora capsici will rot but remain on the plant. The foliage can sometimes remain unaffected while the fruit rots, but the plant will eventually wilt and develop dark stem cankers.

Cut Flower Pest Alerts

Dahlia

Slugs and/or snail damage was suspected on dahlias in Hampshire Co. this week. For more information, see our recent pest alert and vegetable notes article about slugs.

Slugs and/or snail damage was suspected on dahlias in Hampshire Co. this week. For more information, see our recent pest alert and vegetable notes article about slugs.

Powdery mildew (PM) was confirmed on dahlias in Hampshire Co. this week. PM fungi tend to be very host-specific; that is, they are specialized to infect only plants in one genus or one family. The species that infects dahlias can infect many different plants in the aster family. As with all PMs, it requires high humidity for sporulation and infection. On dahlias, PM looks like a white film on top of plant leaves. Controling PM involves scouting regularly for early signs of the diseases. Epidemics that seem to develop overnight are often the result of undetected low-level infections that have spread spores throughout the greenhouse. Rogue infected plants or prune out diseased tissue. Immediately place diseased material into a plastic bag to prevent spores from spreading. In the greenhouse, PM can be managed by reducing nighttime humidity using fans or by a combination of heating and venting. Avoid overcrowding of plants and provide good air movement. Eliminate all weed hosts and volunteer plants. Unlike most fungi, PMs only colonize the surface of plants, making chemical eradication possible. Numerous fungicide products are registered for PM control on ornamentals. Check labels for host appropriateness. Sulfur may cause plant injury if applied when temperatures are above 85° F. Because the genera and species of fungi causing PMs are diverse, there may be some variation in fungicide effectiveness across crops.

Powdery mildew (PM) was confirmed on dahlias in Hampshire Co. this week. PM fungi tend to be very host-specific; that is, they are specialized to infect only plants in one genus or one family. The species that infects dahlias can infect many different plants in the aster family. As with all PMs, it requires high humidity for sporulation and infection. On dahlias, PM looks like a white film on top of plant leaves. Controling PM involves scouting regularly for early signs of the diseases. Epidemics that seem to develop overnight are often the result of undetected low-level infections that have spread spores throughout the greenhouse. Rogue infected plants or prune out diseased tissue. Immediately place diseased material into a plastic bag to prevent spores from spreading. In the greenhouse, PM can be managed by reducing nighttime humidity using fans or by a combination of heating and venting. Avoid overcrowding of plants and provide good air movement. Eliminate all weed hosts and volunteer plants. Unlike most fungi, PMs only colonize the surface of plants, making chemical eradication possible. Numerous fungicide products are registered for PM control on ornamentals. Check labels for host appropriateness. Sulfur may cause plant injury if applied when temperatures are above 85° F. Because the genera and species of fungi causing PMs are diverse, there may be some variation in fungicide effectiveness across crops.

Broad mites were confirmed on outdoor dahlias in Middlesex Co. Broad mites are favored by high temperatures and feed mainly on the lower surface of young leaves, causing downward puckering and leaf distortion. They may also feed on flowers. They are especially troublesome in greenhouses but can also cause damage in the field, although field infestations usually originate from infested greenhouse transplants. To manage broad mites, remove and destroy infested plant and crop debris. Clean greenhouse surfaces with a disinfectant such as quaternary ammonium. To break the mites’ lifecycle, leave tunnels and greenhouses unheated for a few weeks in the winter, if possible. It is possible to control broad mites with biological control using predaceous mites. Note that high tunnel biological control programs are more effective in early summer (especially when implemented in conjunction with spraying hot spots), but by late summer they are generally not effective. Biological control can be successful in greenhouses but are generally less effective outdoors. The predatory mite species Neoseiulus cucumeris and N. californicus are typically recommended, but other species may also be effective. Work with your biological control supplier to develop a plan. Scout potential host plants early and often, as treating small populations is more effective than managing dense populations. Check miticide labels to ensure they are labeled specifically for broad mite. Broad mites often hide within tender buds and new growth, so miticides that only have contact activity, including horticultural oils and insecticidal soaps, will not be very effective. Translaminar miticides such as abamectin, spiromesifen, and chlorfenapyr tend to be more effective. If leaf canopies are dense, coverage on the undersides of leaves is difficult. Miticides with acropetal systemic activity will be translocated to the growing tip where mites are feeding, delivering greater control.

Broad mites were confirmed on outdoor dahlias in Middlesex Co. Broad mites are favored by high temperatures and feed mainly on the lower surface of young leaves, causing downward puckering and leaf distortion. They may also feed on flowers. They are especially troublesome in greenhouses but can also cause damage in the field, although field infestations usually originate from infested greenhouse transplants. To manage broad mites, remove and destroy infested plant and crop debris. Clean greenhouse surfaces with a disinfectant such as quaternary ammonium. To break the mites’ lifecycle, leave tunnels and greenhouses unheated for a few weeks in the winter, if possible. It is possible to control broad mites with biological control using predaceous mites. Note that high tunnel biological control programs are more effective in early summer (especially when implemented in conjunction with spraying hot spots), but by late summer they are generally not effective. Biological control can be successful in greenhouses but are generally less effective outdoors. The predatory mite species Neoseiulus cucumeris and N. californicus are typically recommended, but other species may also be effective. Work with your biological control supplier to develop a plan. Scout potential host plants early and often, as treating small populations is more effective than managing dense populations. Check miticide labels to ensure they are labeled specifically for broad mite. Broad mites often hide within tender buds and new growth, so miticides that only have contact activity, including horticultural oils and insecticidal soaps, will not be very effective. Translaminar miticides such as abamectin, spiromesifen, and chlorfenapyr tend to be more effective. If leaf canopies are dense, coverage on the undersides of leaves is difficult. Miticides with acropetal systemic activity will be translocated to the growing tip where mites are feeding, delivering greater control.

--Written by Angie Madeiras, adapted for Pest Alerts by Hannah Whitehead

Contact Us

Contact the UMass Extension Vegetable Program with your farm-related questions, any time of the year. We always do our best to respond to all inquiries.

Vegetable Program: 413-577-3976, umassveg@umass.edu

Staff Directory: https://ag.umass.edu/vegetable/faculty-staff

Home Gardeners: Please contact the UMass GreenInfo Help Line with home gardening and homesteading questions, at greeninfo@umext.umass.edu.

Summer Annual Grass Weed Management

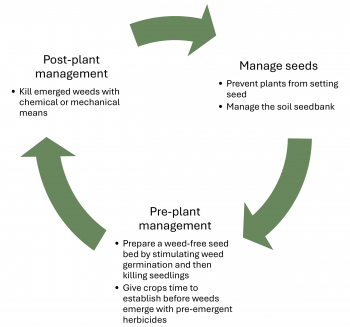

The other week we published an article exploring grass identification, focusing on the most common summer annual weeds. Now that you know what grass species you have in your field, we are going to focus on what you can do to manage them. As a group, grasses are slightly harder to kill than broadleaf weeds once they are established, partially because their growing point is below the soil surface, so any technique that does not target the grass below that point is less likely to work1. Contact herbicides (e.g., Aim/carfentrazone or Rely/glufosinate) and flaming are less successful at killing grass weeds than systemic herbicides (e.g., Roundup/glyphosate). Killing established grass is the last line of defense when thinking about grass weed management—first think about reducing seed set, then killing emerged grasses before planting, and finally in-season control [Fig 1].

The other week we published an article exploring grass identification, focusing on the most common summer annual weeds. Now that you know what grass species you have in your field, we are going to focus on what you can do to manage them. As a group, grasses are slightly harder to kill than broadleaf weeds once they are established, partially because their growing point is below the soil surface, so any technique that does not target the grass below that point is less likely to work1. Contact herbicides (e.g., Aim/carfentrazone or Rely/glufosinate) and flaming are less successful at killing grass weeds than systemic herbicides (e.g., Roundup/glyphosate). Killing established grass is the last line of defense when thinking about grass weed management—first think about reducing seed set, then killing emerged grasses before planting, and finally in-season control [Fig 1].

Manage the seeds

To manage annual weeds, focus primarily on managing the seeds. The only way that an annual can survive from year to year is through its seed. If you manage the seeds, you will improve your weed control in the long term. Seeds can be managed in two ways:

- Reducing seed set

- Drawing down the number of seeds stored in the soil

The easiest way to reduce seed set is to kill the weed before it flowers. But sometimes you just do not have time to manage weeds before a lot of seed is set. If you see a lot of seed heads out in your field right now, you know those seeds will end up in your soil and you will have a lot of summer annual grass weeds next year. But do not despair. Grass seeds in the soil are relatively easy to manage because annual grasses germinate readily, making them vulnerable to the pre-plant strategies below, and whatever seed does not germinate will decompose relatively quickly2,3. Below are some strategies to consider for next summer.

Pre-plant Management

Pre-plant strategies can give your crop a head start in establishing, which can then convey a competitive edge to your crop over weeds. There are a few different strategies that can provide a weed-free planting bed.

-

Tarping

Tarping is a strategy that kills weeds by blocking access to light and effectively starving the weed4. This process is called etiolation. Tarps are generally 5-6 mils (0.005-0.006 inches) thick, black on one side, and white on the other. They can be purchased at agricultural supply stores and reused for several years. Tarping can only kill weeds that have germinated and are growing; it will not kill dormant weed seeds. For targeting summer annual weeds, tarping involves the following:

- Prepare a seedbed in the spring. This will both stimulate weed seed germination and reduce the risk of bringing new seeds to the soil surface after removing the tarp.

- Put a tarp over the soil and weigh it down. Place the black side of the tarp up to absorb as much light as possible and weigh the tarp down so there is good soil-tarp contact. This will warm the soil to stimulate seed germination.

- Leave the tarp on the soil for at least 3 weeks, but do not remove the tarp until right before you plan to plant. Uncovered soil will allow weed growth, and we want to prevent that for as long as possible.

- Plant your crop as soon as you remove the tarp and reduce soil disturbance as much as possible once removed. Any disturbance could stimulate the germination of new weed seeds.

-

Stale Seedbed Technique

Creating a stale seedbed is a technique that kills weeds by stimulating as much germination as possible and then killing germinated weeds before planting. The process is:

- Prepare a seedbed. Again, the idea is to stimulate germination and reduce soil disturbance later. Light, oxygen, soil moisture, and temperature all help break weed seed dormancy, so tillage and bed shaping will stimulate germination. Also make sure soil is adequately moist—irrigate if necessary.

- Once the weed seeds germinate (about 1 week), kill the weeds using herbicides, flaming, or shallow cultivation. Cultivate as shallow as possible. If you bring any new seeds to the soil surface with this cultivation it will stimulate the germination of new weed seeds.

- This process can be repeated (stimulating germination with tillage and irrigation and then killing seedlings) if there is time before planting.

- Plant into the prepared bed, with as little soil disturbance as possible.

-

Pre-emergent Herbicides

Many pre-emergent herbicides are effective against annual grasses. Using a pre-emergent herbicide is helpful for providing several weeks of a weed-free soil surface while crops become established. Select a pre-emergent herbicide that has good efficacy against the species that you know were most prevalent in your field the prior year (this is why grass identification is important). Read the label carefully to get good control. Some herbicides act on germinating weeds, so they need to be incorporated into the soil through tillage or rainfall. Others act on weeds that are just emerging from the soil, so they need to remain on the soil surface. They often need adequate soil moisture to be active. If you are applying a pre-emergent herbicide that needs to remain on the soil surface, reduce soil disturbance as much as possible after applying. Pre-emergent herbicides will be effective for different lengths of time, depending on many different factors including: soil texture, soil organic matter content, soil moisture, and herbicide chemistry. In general, expect control for about 8-12 weeks. See Table 1 for a list of pre-emergent herbicides that can control grasses.

Post-planting Management

No matter what type of pre-planting weed management strategy you use, do not expect it to be effective throughout the entire life of your crop. Summer annual weeds germinate in warmer soils, so they can become an issue later in the growing season. An established crop should experience less yield reduction from weeds than an emerging crop, but any uncontrolled weeds can set seed and make weed control more difficult the next year. Here are some strategies for post-planting management of summer annual grass weeds:

-

Cultivation

Cultivation buries, cuts, and/or uproots weeds, which then leads to plant death through desiccation. Cultivation efficacy is highly variable, dependent on many factors including: cultivation tool, soil texture and moisture, weed species and growth stage, and weed-crop selectivity. All these factors make it somewhat difficult to generalize, but cultivation is almost always more effective when weeds are small. Since grasses have a low growing point, narrow leaves, and often have fibrous root systems they can be less susceptible than broadleaf annuals to many cultivation tools. Consider stacking tools by using multiple types of cultivation equipment together in a single pass. Stacking tools should lead to greater cultivation efficacy5.

-

Post-Emergent Herbicides

The post-emergent herbicides clethodim (Select Max) and sethoxydim (Poast) are both systemic group 10 herbicides that control grasses but do not affect broadleaf plants. They are labeled for use in most vegetable crops. Since they are systemic, they need to be applied to actively growing grasses to be most effective. The grasses do not have to be large, just actively growing. For most annual grass weeds, Poast should be applied before the grasses reach 4-8 inches tall, and Select Max should be applied before the grasses reach 2-6 inches tall. Counterintuitively, if you apply these herbicides to sick or damaged grasses, they will not work as well. Unlike a contact herbicide, these materials do not need to cover the entire plant to get good control, but the herbicide must stay on the grass long enough to enter the phloem and be transported to the site of action. Be sure to add any recommended surfactant to the herbicide to help it stick to the grass blade and follow label directions for including urea ammonium nitrate (UAN) or ammonium sulfate (AS) in the spray solution to ensure the material enters the phloem effectively and to maximize efficacy. Since these herbicides need to move within the plant to be active, do not expect the grass to show symptoms immediately. Generally, do not tank mix a systemic herbicide with a contact herbicide, or the foliage will desiccate before the systemic herbicide has time to enter the leaf and kill the weed.

Hopefully by combining pre-plant and post-plant weed control techniques, you can reduce the grass weeds growing in your crops and setting seed. With reduced seed set, you will be able to draw down the number of summer annual grass weed seeds in your seedbank relatively quickly, and weed control will become easier.

| Table 1. Herbicides to control summer annual grass weeds | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trade Name (Active Ingredient) | Barnyardgrass | Crabgrass | Foxtail | Goosegrass | Crops Registered | Other Requirements of Note |

| Need to be incorporated through tillage or water (rainfall or irrigation | ||||||

| Aquestra 4F (sulfentrazone) | C | C | Beans, brassicas, cucurbits, eggplant, okra, peas, peppers, potatoes, rhubarb, rutabaga/turnips, tomatoes | Needs some soil moisture to be activated. This can come from available soil moisture, irrigation, or rainfall. | ||

| Curbit (ethalfluralin) |

(E) |

C (E) |

C (E) |

C | Cucurbits, pumpkins | Needs to be activated with 0.5 inches of water through rainfall or irrigation. |

| Devrionol 2-XT (napropamide) |

C | C | C | C | Asparagus, basil, brassicas, eggplant, peppers, sweet potato, tomato | All weed growth, crop stubble, or leaf litter must be worked into the soil before application. |

| Dual Magnum (s-metolachlor) |

C (E) |

C (E) |

C (E) |

C | Asparagus, beans, beet/chard, brassicas, carrots/parsnips, sweet corn, curcurbits, garlic, onion, peas, peppers, potatoes, pumpkin, rhubarb, spinach, tomatoes | Indemnified label for many vegetable crops. |

| Eptam (EPTC) |

C (E) |

C (E) |

C (E) |

C | Beans, potatoes | Must be incorporated into the soil quickly after application, preferably in the same operation. If incorporating with tillage, 2 passes are recommended for more consistent coverage. Incorporate 2-3 inches deep. |

| Matrix SG (rimsulfuron) |

C | C | C | Potatoes, tomatoes | Incorporate into the soil with irrigation within 5 days of application. | |

| Metribuzin (metribuzin) |

C | Pc | Pc | C | Asparagus, carrots/parsnips, peas, potatoes, tomatoes | |

| Outlook (dimethenamid) |

C | C | C | C | Beans, beets/chard, sweet corn, garlic, leeks, onions, potatoes, radish, rutabaga/turnips, sweet potatoes | |

| Prefar 4-E (bensulide) |

C (E) |

C (E) |

C (E) |

C | Brassicas, celery, cucurbits, eggplant, garlic, lettuce, onions, parsley/cilantro, peppers, pumpkins | All weed growth, crop stubble, or leaf litter must be worked into the soil before application. |

| Prowl H2O (pendimethalin) |

C (E) |

C (E) |

C (E) |

C | Asparagus, beans, brassicas, carrots/parsnips, celery, sweet corn, eggplant, garlic, artichoke, leeks, onions, peas, peppers, potatoes, tomatoes | If incorporating with tillage, 2 passes are recommended for more consistent coverage. |

| Ro-Neet (cycloate) |

C (G) |

C (G) |

C (G) |

Carrots/parsnips, rutabaga/turnips | All weed growth, crop stubble, or leaf litter must be worked into the soil before application. | |

| Sonalan HFP (ethalfluralin) |

C (E) |

C (E) |

C (E) |

Beans, potatoes | Incorporate 2-3 inches into the soil within 48 hours of application. | |

| Treflan HFP (trifluralin) |

C (E) |

C (E) |

C (E) |

Asparagus, beans, brassicas, carrots/parsnips, celery, cucurbits, eggplant, okra, onions, peas, peppers, potatoes, radishes, rutabaga/turnips, tomatoes | Weed growth, crop stubble, and leaf litter must be at manageable levels to uniformly incorporate 2-3 inches into the soil after application. Incorporate mechanically, 2 passes may be necessary. | |

| Should remain on the soil surface | ||||||

| Caparol 4L (prometryn) |

C (G) |

C (E) |

C (G) |

C | Carrots/parsnips, celery, okra, parsley/cilantro, rhubarb | Moisture is needed to activate. |

| Chateau EZ (flumioxazin) |

C | C | C | C | Asparagus, beans, garlic, artichoke, peppers | Moisture is needed to activate. |

| Command 3ME (clomazone) |

Hr (G) |

Hr (G) |

C (G) |

C | Asparagus, basil, beans, brassicas, cucurbits, parsley/cilantro, peas, peppers, pumpkins, rhubarb, sweet potatoes | Can be shallow incorporated no deeper than 2 inches if soil crusting, compaction, or weed emergence has occurred. |

| Lorox DF (linuron) |

C (G) |

C (G) |

C (G) |

C | Asparagus, beans, carrots/parsnips, celery, parsley/cilantro, peas, potatoes, rhubarb | Moisture is needed to activate. |

| C – Provides control according to the label Pc – Provides partial control according to the label Hr – Provides control using high rate according to the label (E) – Excellent control according to Cornell efficacy data (G) – Good control according to Cornell efficacy data |

||||||

References

- Boyd, N. S., Brennan, E. B. & Fennimore S. A. Stale seedbed technique for organic vegetable production. Weed Tech. 20, 1052-1057 (2006).

- Benvenuti, S. & Macchia, M. Reduction after different stale seedbed techniques in organic agricultural systems. Italian J of Agron. 1, 11-21 (2006).

- Thompson, K. & Grime, J. P. Seasonal variation in the seed banks of herbaceous species in ten contrasting habitats. J Ecol. 67, 893-897 (1979).

- Kubalek, R., Granatstein, D., Collins, D. & Miles, C. Review of tarping and a case study on small-scale organic farms. Hort Tech. 32, 119-128 (2022).

- Gallandt, E.R., Brainard, D. & Brown B. Developments in physical weed control. In Zimdahl, R.L. (ed.) Integrated weed management for sustainable agriculture. Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing, Cambridge, UK (2018).

--Written by Maria Gannet, UMass Extension Weeds Specialist

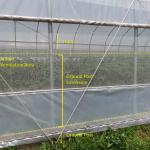

A Guide to Preparing High Tunnels for Extreme Weather

--Compiled from Vermont Vegetable & Berry Growers’ Association input by Becky Maden, Chris Callahan, Vern Grubinger, and Andy Chamberlain, University of Vermont Extension. Originally published at https://blog.uvm.edu/cwcallah/2024/08/13/a-guide-to-preparing-high-tunnels-for-extreme-weather/, August 13, 2024.

Introduction

High tunnels and greenhouses provide protection for crops, extend the growing season, and improve yield and quality. However, climate change brings both a higher frequency and increased intensity of extreme weather events. It is important to think about how high tunnel structures can best be built and modified to endure the extremes. The information below is a summary of experiences shared by the growers of the Vermont Vegetable and Berry Growers Association (VVBGA). Individual grower comments and references for more information are provided following the summary.

BEFORE YOU BUILD

Siting

Invest in site selection and development before construction begins. Avoid wet or flood prone areas. Build a raised pad for the tunnel that elevates it from surrounding land. This allows for drainage of rain in warm weather and snow melt in colder weather when the ground may be frozen.

Before driving in ground posts, install drainage, leaving 18-24″ of space between a French drain and ground posts. Make sure there is a place for the water to drain to that is not an adjacent field or tunnel. Remember that tunnels shed a lot of water in rainstorms. That water needs somewhere to go quickly.

Leave room for snow clearing between and around tunnels. Consider both the room needed for snow clearing equipment and also where the snow will go.

Consider prevailing winds and air movement. Site tunnel where there will be good cross ventilation, but not high winds. Plant windbreaks if necessary.

DESIGN

Structure

When purchasing a tunnel, choose as much structural reinforcement as possible to support snow loads and high winds. Be sure to account for primary crop load (tomatoes, hanging baskets, etc.) This may include the size of structural pipes, number of trusses and truss bracing, wind / corner bracing, and strong purlin to bow connections (cross braces and through-bolting vs. strapping.)

Build strong end-walls and make sure they are anchored to the ground to prevent uplift (the upward force that can occur in high wind events). End walls are often the weak point in the design and once they lift or otherwise fail, wind will wreak havoc on the rest of the structure.

A steeper roof pitch (6:12 or 26.6°) can promote snow shedding. Even one degree less can make a difference. The gothic shape is designed to shed snow.

Ventilation

Ventilation fans can push hot air out and draw in cooler and/or less humid air. These systems should be designed well to ensure that they are actively drawing air through the tunnel.

If relying on passive ventilation, install large openings for maximum airflow. This starts with high sides for roll up or roll down systems, which may require adding extended ground posts.

End walls should have large openings (doors, gable vents).

Ridge vents will optimize passive air flow because heat rises.

Be careful to avoid mixing passive and mechanical ventilation at the same time. An exhaust fan running with the sides rolled up will pull air from the path of least resistance (the closest opening of the roll-up side), and may provide little benefit.

For lower cost tunnels without automation, gable end or butterfly vents are a good option to improve passive ventilation. These can be easily installed after construction. Consider multiple vents or larger single vents.

Controls

Consider investing in automated systems and controls that may respond to changes in temperature, increased wind, and even precipitation more quickly than you can.

STRATEGIES FOR EXISTING STRUCTURES

Structural Maintenance

Check plastic before anticipated storms. Patch holes, secure wiggle wire, tighten loose areas to reduce flapping .

Check structure seasonally and tighten any loose brackets, replace rotting lumber on endwalls, hipboards, and baseboards. Plumb endwalls as needed.

Rain and Flooding

For tunnels already built, install drainage, swales, or other water diversions to steer water away from tunnels. Avoid excavation within 18-24” of ground posts which can reduce their resistance to uplift.

Build raised beds and use mulched pathways inside tunnels. Adding organic matter to tunnel soils can improve the “sponging” capacity of the soil and water infiltration. In tunnel walkways, wood chips can help absorb water and reduce compaction.

Wind

Shut all the doors and keep the wind out. This may mean extra latches on doors, bracing doors with cinder blocks and rebar, tying down roll-up sides, securing louvers and ridge vents, etc.

Patch all plastic tears and check wiggle wire fastening.

Add extra trusses and bracing. Some growers have trusses added to every bow and invest in additional wind or corner bracing.

Snow

Double layer, inflated plastic helps shed snow.

Consider temporary bracing with 2×4 posts under hoops especially in Quonset hut style tunnels or those with weaker hoops.

Clear snow evenly from both sides, a little bit at a time, to prevent eccentric loading on the bows (takes longer, but may prevent damage).

Heat the house to melt snow as it falls. Heating the house, even minimally, can prevent accumulation of snow and minimize snow clearing needed.

Gear up! Consider getting a snow shovel with an extra-long handle, a wide long handled broom with soft bristles, and a good pair of snowshoes.

Heat

Use shade to keep crops cool. Use 30% shade cloth. Research shows that white shade cloth allows more plant available light through but for short durations, black is effective too.

Coating the exterior of the tunnel with a washable material provides temporary cooling. Surround WP, lime, or Koolray are recommended.

Lighter colored mulches help cool the soil such as straw, white landscape fabric or white plastic. Mulches can also help keep soil evenly moist during hot periods.

Moving air through the tunnel helps plants stay cool. Passive ventilation such as roll up sides, butterfly vents, and doors should be fully open during hot stretches. See above for design guidance.

Taller ground posts (extra roll-up side area) can improve passive ventilation flow rate. This also provides more flow area to compensate for restricted air flow due to any insect netting.

Ventilation fans can push hot air out and draw in cooler and/or less humid air. See above for design guidance.

Circulation fans such as horizontal air flow fans (HAF) or vertical air flow fans (VAF) move air through crops which helps keep plants cool, reduces humidity, and disease, and can increase pollination during hot humid stretches. See above for design guidance.

To reduce plant stress during hot periods, be sure to keep plants well-watered; do so during cooler times of the day. Check the soil regularly to make sure it is moist.

Adjust horticultural practices. For crops that are prone to sunscald or sunburn, do not prune the leaves or suckers directly above fruit and expose it to direct sunlight. Reduce pruning stress during hot periods.

Only use insect netting if necessary for crop production; it can reduce airflow and increase tunnel temperatures. If using netting, use the largest mesh opening possible to exclude the target pest(s) and increase airflow area and ventilation accordingly.

Consider worker safety. If the tunnels are too hot for plants, they are too hot for humans. Shift the hours spent working in tunnels to early mornings and cool evenings to reduce stress on workers.

When retrofitting perimeter insulation take care to angle the excavation away from the ground posts to avoid soil disturbance which could loosen them and reduce uplift resistance.

News

SARE Farmer Grant Program Now Accepting Applications

Farmers in the Northeast can apply for up to $30,000 in funding for sustainable agriculture projects starting in 2025. These projects can range from experiments to on-farm events and demonstrations or other educational activities.

The Call for 2025 Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) Farmer Grants is now available. Approximately $850,000 has been allocated to fund projects. Awards of up to $30,000 are available. Proposals are due no later than 5:00 p.m. EST on November 12, 2024.

Q&A Sessions are taking place alternating Tuesdays and Wednesdays in October. Register once to attend any of the sessions.

Sessions will take place on: Oct 8, 16, 22, 30. from 12 to 1 EST

Learn more about the Farmer Grant Program.

EPA Releases Endangered Species Act Herbicide Strategy

On Tuesday August 20, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released its plan to reduce the risk of herbicide applications to endangered species. You can read the news release here and download the full plan at this site. The EPA is calling their plan the “Herbicide Strategy” (which should not be confused with the herbicide named Strategy).

The plan is designed to keep herbicide products available to growers who need them, while simultaneously protecting endangered and threatened species from these products. The overall goal of the plan is to keep all herbicides on the farm by reducing runoff and drift. Pesticide movement is to be reduced by adopting appropriate management strategies. These strategies are assigned points based on how much they do to mitigate off-target movement. Growers need to accumulate a certain number of points based on the risk the herbicide poses to any endangered species whose range includes the farm.

This is a new approach to protecting endangered and threatened species (called “listed” species). Previously, the EPA had attempted to evaluate each pesticide’s potential effect on each listed species. This process was overly slow and laborious and resulted in the EPA being out of compliance with the Endangered Species Act (ESA) for many decades. This new approach should bring the EPA back into compliance within a reasonable timeframe. Herbicides are the most widely used group of pesticides, so the EPA began this new mitigation strategy with them. Now they have begun to include insecticides—you can read the draft strategy for insecticides here, released on July 25, and EPA is holding an informational webinar on the insecticide strategy on September 5. See Events section below for details.

The UMass Vegetable Team will certainly keep you updated about what these changes mean for your farm. To read more about EPA’s efforts to protect endangered species from pesticides, see their website: https://www.epa.gov/endangered-species

Call for Comments for Potential Mancozeb Registration Changes

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released their proposed interim registration review decision for mancozeb in July 2024. Mancozeb is a multisite mode of action fungicide used for the prevention and control of fungal pathogens in fruit and vegetable crops, ornamental plants, and turf grass.

There is an open comment period for the public to provide responses to the proposed risk mitigation revisions and how they could impact production. The comment period ends on September 16, 2024. To view the amended proposed interim registration review in its entirety, see Docket No. EPA-HQ-OPP-2015-0291 at www.regulations.gov. For instruction on how to submit comments, visit https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/07/17/2024-15650/pesticide-registration-review-proposed-decisions-for-several-pesticides-notice-of-availability-and.

Proposed changes relevant to vegetable crops include new spray-drift reduction measures, new personal protective equipment requirements and engineering controls, spray drift management measures, and changes to REIs (broccoli, cabbage to 6 days; pepper, tomato, and cucurbit to 3 days). The proposed revisions also include several use terminations, including all uses in grapes. Rutgers Cooperative Extension has provided a good summary of all of the proposed changes here.

Events

Rural Energy for America Program (REAP) Grant Webinar

When: Thursday, August 29, 2024, 10:30am-12pm

Where: Online

Registration: Click here to register.

The Massachusetts Farm Energy Program will provide an overview of the application process and requirements for the USDA's Rural Energy for America Program (REAP) Grant. The REAP grant provides guaranteed loan financing and grant funding to agricultural producers and rural small businesses for renewable energy systems or to make energy efficiency improvements. Agricultural producers may also apply for new energy efficient equipment and new system loans for agricultural production and processing.

Questions? Contact the Massachusetts Farm Energy Program at info@massfarmenergy.com or 413-727-3090.

EPA Webinar on Draft Strategy to Better Protect Endangered Species from Insecticides

When: Thursday, September 5, 2024, 1-2pm

Where: Online

Registration: Click here to register.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) will hold a public webinar on September 5, 2024, from 1-2 PM ET to provide an overview of its draft Insecticide Strategy. Released on July 25, 2024, the draft strategy furthers the agency’s work to adopt early, practical protections for federally endangered and threatened (listed) species and designated critical habitats from the use of conventional agricultural insecticides.

The draft strategy identifies protections that EPA will consider when it registers a new insecticide or reevaluates an existing one. In developing this draft strategy, EPA identified protections to address potential impacts for more than 850 species listed by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS). The draft strategy identifies protections earlier in the pesticide review process, thus creating a far more efficient approach to evaluate and protect the FWS-listed species that live near these agricultural areas.

The draft insecticide strategy uses the most updated information and processes to determine whether an insecticide will impact a listed species and identify protections to address any impacts. To determine impacts, the draft strategy considers where a species lives, what it needs to reproduce (e.g., food or pollinators), where the pesticide will end up in the environment, and what kind of the pesticide might have if it reaches the species. These refinements greatly reduce the need for pesticide restrictions in situations that do not benefit species.

The webinar will include:

- Discussion of the proposed three-step framework to identify potential population-level impacts to species, identify mitigation measures to address these impacts, and determine the geographic extent of the mitigation measures;

- An overview of case studies to illustrate how the framework could be applied to representative insecticides and how EPA expects to implement the strategy in its registration and registration review actions; and

- An opportunity for the public to ask questions.

The webinar will be open to the public on the GoTo webinar platform, and all interested stakeholders are invited to attend. The agenda and instructions for joining the webinar will be sent to registered attendees.

Dahlia Farm Walk at Grant Family Farm

When: Tuesday, September 24, 4-6pm

Where: Grant Family Farm, 866 Main St, West Newbury, MA

Registration: Free, but please register in advance here.

Join us in West Newbury on September 24 for a farm walk all about dahlias. We’ll tour Grant Family Farm and hear from farmers Alice and Chris. The UMass Extension vegetable program will also host a listening session to learn about your challenges and needs related to growing cut flowers.

Twilight Meeting: Climate Impacts on Weed Management and Soil Health - South Deerfield, MA

When: Tuesday, October 8, 2024, 4-6pm, with a light supper to follow

Where: UMass Crop & Livestock Research & Education Farm, 89 River Rd., South Deerfield, MA, 01373

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

How are climate change and hotter temperatures affecting our soils? Often, practices like reducing tillage and cover cropping are recommended to improve soil health, reduce risk of topsoil loss and enhance resilience to drought and flood—practices that can also affect weed management. UMass Extension will discuss general impacts of climate change on soil health and highlight current research on updating recommendations for planting timing and overwintering survival of cover crop species in MA. Maria Gannett, UMass Extension Weeds Specialist, will relate these strategies to how they can impact weed management.

1 pesticide recertification credit is available for this program.

This event is co-sponsored by CISA as part of their Adapting your Farm to Climate Change Series.

Food Safety & Storage in a Warmer New England

When: Tuesday, October 15, 4-5:30 pm

Where: Kitchen Garden Farm, 131 S. Silver Lane, Sunderland, MA, 01375

Registration: Free, registration info coming soon!

Join UMass Extension, CISA, and UVM Extension for a climate-themed twilight meeting at Kitchen Garden Farm in Sunderland, MA!

- Lilly Israel and Max Traunstein, Owners, Kitchen Garden Farm - Tour of the farm's postharvest and food production facilities, and discussion on how the farm is considering climate change and food safety in its operations.

- Chris Callahan, Extension Associate Professor, UVM Extension Ag Engineering - Precooling resources, sizing CoolBots and coolers, condensation management, and guidance on sorting/culling product for storage

- Lisa McKeag, Extension Educator, UMass Extension - Overview of potential climate impacts on food safety

This event is co-sponsored by CISA as part of their Adapting your Farm to Climate Change series.

Save the Date! Gaining Ground Farm Tour

When: Thursday, October 17, 2024, 4-6pm

Where: Gaining Ground, 341 Virginia Rd., Concord, MA 01742

Join New Entry and UMass Extension for a farm tour of Gaining Ground Farm in Concord, MA!

Registration and event details coming soon.

Vegetable Notes. Maria Gannett, Genevieve Higgins, Lisa McKeag, Susan Scheufele, Alireza Shokoohi, Hannah Whitehead, co-editors. All photos in this publication are credited to the UMass Extension Vegetable Program unless otherwise noted.

Where trade names or commercial products are used, no company or product endorsement is implied or intended. Always read the label before using any pesticide. The label is the legal document for product use. Disregard any information in this newsletter if it is in conflict with the label.

The University of Massachusetts Extension is an equal opportunity provider and employer, United States Department of Agriculture cooperating. Contact your local Extension office for information on disability accommodations. Contact the State Center Directors Office if you have concerns related to discrimination, 413-545-4800.

![Black shade cloth. Both black and white shade cloth provide some reduction of heat gain from incident solar radiation.] A high tunnel covered with black shade cloth.](/sites/ag.umass.edu/files/styles/150x150/public/newsletters/images/image_9.jpg?itok=tt0KzZis)