To print this issue, either press CTRL/CMD + P or right click on the page and choose Print from the pop-up menu.

Crop Conditions

Harvest lists are getting long now, with tunnel cukes, tomatoes and peas starting to come in, along with bunches of radishes, beets, carrots, and scallions, and bunching broccoli, fennel, and summer squash bringing those early summer vibes. Those of you growing strawberries know the crop is coming on strong and sweet and many u-pick fields will be open this weekend. The weather has been pretty good for planting, with melons and sweet potatoes going in, and pumpkin seeding underway. Sweet corn is tasseling now, and the earliest plantings on plastic are silking. This quote from Jim Ward at Ward’s Berry Farm in Sharon, MA sums things up well: "Been buzzing around the farm on cultivating tractors almost all the daylight hours for the last week. Got my whole crew bought into the 'critical weed-free period' and it feels like we are in it for nearly every crop we have. Most things are looking real good though, incredible what the heat and sun and ample water can do!” Driving around the valley scouting this week we were struck by all the activity, and the long hot days folks are already putting, in keeping things weeded and picked—we are so grateful to all the farmworkers who toil through the heat to keep us so well fed!

Harvest lists are getting long now, with tunnel cukes, tomatoes and peas starting to come in, along with bunches of radishes, beets, carrots, and scallions, and bunching broccoli, fennel, and summer squash bringing those early summer vibes. Those of you growing strawberries know the crop is coming on strong and sweet and many u-pick fields will be open this weekend. The weather has been pretty good for planting, with melons and sweet potatoes going in, and pumpkin seeding underway. Sweet corn is tasseling now, and the earliest plantings on plastic are silking. This quote from Jim Ward at Ward’s Berry Farm in Sharon, MA sums things up well: "Been buzzing around the farm on cultivating tractors almost all the daylight hours for the last week. Got my whole crew bought into the 'critical weed-free period' and it feels like we are in it for nearly every crop we have. Most things are looking real good though, incredible what the heat and sun and ample water can do!” Driving around the valley scouting this week we were struck by all the activity, and the long hot days folks are already putting, in keeping things weeded and picked—we are so grateful to all the farmworkers who toil through the heat to keep us so well fed!

We have a great twilight meeting coming up next Wednesday, at Tangerini's Farm in Millis. We'll hear from farm owner Steve Chiarizio about the new tile drainage system and bioreactor that they installed at the farm last year with the help of Massachusetts FSIG funding. A representative from Alleghany Services, who installed the system, will also be on hand to answer questions. And Maria Gannett (UMass Extension Weed Specialist) and Sue Scheufele (UMass Extension Vegetable IPM Specialist) will talk about sweet corn weed and insect pest management options. We hope you can join us and stay for dinner afterwards—see you there! Please be sure to register in advance. We'll have food and free childcare and need to plan accordingly! Click here for more information and to register.

And we're excited to announce that registration is now open for the 2024 New England Vegetable & Fruit Conference in Manchester, NH! This is a biennial event that brings together farmers, researchers, and Extension personnel from around the region, and it is not one to miss. Visit the conference website for more information and to register!

Vegetable Pest Alerts

Brassicas

Three of the four caterpillar pests of brassicas were seen this week in Hampden Co.: imported cabbageworm, diamondback moth, and cross-striped cabbageworm. More information on each below. Egg laying can be prevented using row covers—use insect netting that traps less heat than spunbonded covers for mid-summer production. Treatment with a pesticide is warranted in heading crops (e.g. cabbage, broccoli) prior to head formation if 20% of plants are infested. Use a 10-15% threshold for leafy brassica crops (e.g. kale, collards) and heading crops after head formation. Labeled conventional products include spinosyns (e.g. Radiant), pyrethroids (e.g. Warrior, Mustang, many others), diamides (e.g. Exirel and Coragen for soil or foliar applications and Verimark for soil applications only), Proclaim, Avaunt, and Torac. Diamide products are more expensive but are systemic, have long residuals, and will also protect against flea beetles, cabbage aphids, and cabbage root maggot. Bt products are effective and selective for caterpillars—e.g. Dipel (OMRI-listed), Xentari. Use a spreader-sticker to help materials adhere to waxy brassica leaves.

Imported cabbageworm: These caterpillars are getting big now and can do significant feeding damage before they pupate. ICW caterpillars are solid green and slightly fuzzy, and grow to be about 1.5” long. They often line up with brassica leaf midribs on the undersides of the leaves, camouflaging themselves very well, but you will know they are there by their big and bountiful frass.

Diamondback moth larvae are also solid green but are slimmer than ICW and have a forked tail and, notably, will thrash around when disturbed and drop from the leaf or your hand on a silk thread. Their feeding often leaves the top layer of the leaf intact, resulting in “window pane” damage (see photo).

Cross-striped cabbageworm usually doesn’t show up in New England until late summer. Seeing it this early indicates that this population overwintered here, probably in a high tunnel where brassica crops were grown into the fall and winter. CSCW caterpillars are light bluish-grey on top and green underneath, with numerous black bands across their backs and a yellow stripe down each side. Unlike the other brassica caterpillar pests, CSCW moths lay their eggs in clusters, resulting in many CSCW caterpillars on a single plant, skeletonizing the plant.

Cucurbits

Bacterial wilt is beginning to develop in cucurbit crops infested with striped cucumber beetles, which vector the pathogen. Most cucurbit crops are susceptible to bacterial wilt, with watermelon being more resistant than other crops. Leaves of infected crops will wilt, and symptoms will travel along vines towards the tips. There is no control for bacterial wilt aside from controlling striped cucumber beetle. See our Striped Cucumber Beetles: Focus on Early Control article for more information.

Bacterial wilt is beginning to develop in cucurbit crops infested with striped cucumber beetles, which vector the pathogen. Most cucurbit crops are susceptible to bacterial wilt, with watermelon being more resistant than other crops. Leaves of infected crops will wilt, and symptoms will travel along vines towards the tips. There is no control for bacterial wilt aside from controlling striped cucumber beetle. See our Striped Cucumber Beetles: Focus on Early Control article for more information.

Nightshades

Colorado potato beetle eggs were observed in Franklin Co. this week. No larvae were observed in this planting. If you plan to control CPB using insecticides, scout now for eggs and take note of when eggs begin to hatch. Insecticides are most effective if they target small larvae. Do not use the same class of pesticides on successive generations in the same year. Labeled conventional products include pyrethroids, neonicotinoids, novaluron (e.g. Rimon), cyromazine (e.g. Trigard), and diamides (e.g. Verimark, Exirel). There is a new RNAi product called Calantha that is not yet registered in MA but may be soon—it is registered in the other New England states. For organic growers, spinosad (e.g. Entrust) is most effective but can only be used 2 times on only 1 generation of CPB per season. Other options for organic growers include azadirachtin products (e.g. Aza-Direct, Azatin O, Neemix) or pyrethrin (e.g. Pyganic), and the bioinsecticide Beauveria bassiana (e.g. Mycotrol O, Botanigard).

Colorado potato beetle eggs were observed in Franklin Co. this week. No larvae were observed in this planting. If you plan to control CPB using insecticides, scout now for eggs and take note of when eggs begin to hatch. Insecticides are most effective if they target small larvae. Do not use the same class of pesticides on successive generations in the same year. Labeled conventional products include pyrethroids, neonicotinoids, novaluron (e.g. Rimon), cyromazine (e.g. Trigard), and diamides (e.g. Verimark, Exirel). There is a new RNAi product called Calantha that is not yet registered in MA but may be soon—it is registered in the other New England states. For organic growers, spinosad (e.g. Entrust) is most effective but can only be used 2 times on only 1 generation of CPB per season. Other options for organic growers include azadirachtin products (e.g. Aza-Direct, Azatin O, Neemix) or pyrethrin (e.g. Pyganic), and the bioinsecticide Beauveria bassiana (e.g. Mycotrol O, Botanigard).

Potato leafhopper: A single PLH adult was observed in a potato crop in Franklin Co. this week. This pest feeds on many vegetable crops but primarily causes damage in potato, eggplant, and beans. PLH feed by piercing leaf tissue and sucking out the plant sap, and, in the process, inject a toxin into the leaf that causes the edges of the leaves to turn yellow then brown and crispy. This symptom is called hopperburn. In potato and eggplant, some materials registered for Colorado potato beetle (CPB) adults will also control leafhopper, including neonicotinoid foliar sprays such as Admire Pro or Assail. These and several other carbamate, synthetic pyrethroid, and organophosphate products are also registered for leafhopper in potato, eggplant, and snap beans. Sivanto (flupyradifurone) is a newer product in a novel class of chemistries, the butenolides, that works against sucking pests, including PLH. It is also labeled for CPB control. See the appropriate crop section of the New England Vegetable Management Guide for full lists of labeled materials. For organic growers, PyGanic (pyrethrin) is the most effective material. It is a contact insectide that breaks down in sunlight, so getting good coverage of undersides of leaves is important and spraying late in the day may provide better control. Adding azadiractin as a tank-mix may improve efficacy, especially once nymphs are present.

Potato leafhopper: A single PLH adult was observed in a potato crop in Franklin Co. this week. This pest feeds on many vegetable crops but primarily causes damage in potato, eggplant, and beans. PLH feed by piercing leaf tissue and sucking out the plant sap, and, in the process, inject a toxin into the leaf that causes the edges of the leaves to turn yellow then brown and crispy. This symptom is called hopperburn. In potato and eggplant, some materials registered for Colorado potato beetle (CPB) adults will also control leafhopper, including neonicotinoid foliar sprays such as Admire Pro or Assail. These and several other carbamate, synthetic pyrethroid, and organophosphate products are also registered for leafhopper in potato, eggplant, and snap beans. Sivanto (flupyradifurone) is a newer product in a novel class of chemistries, the butenolides, that works against sucking pests, including PLH. It is also labeled for CPB control. See the appropriate crop section of the New England Vegetable Management Guide for full lists of labeled materials. For organic growers, PyGanic (pyrethrin) is the most effective material. It is a contact insectide that breaks down in sunlight, so getting good coverage of undersides of leaves is important and spraying late in the day may provide better control. Adding azadiractin as a tank-mix may improve efficacy, especially once nymphs are present.

Broad mites were identified in high tunnel peppers in western MA this week. These tiny mites feed in the growing point of pepper plants, causing leaf distortion and russeting on fruit. We most often see broad mite damage in peppers grown in high tunnels. Control is difficult if infestations are only noticed after symptoms appear on fruit, so scouting early for leaf distortion symptoms in young plants is key. Commercially available predatory mites (Neoseiulus/Amblyseius cucumeris and N. californicus) can effectively manage broad mites—release at planting if you have a history of infestations. Mite-specific pesticides can be used but may have negative impacts on beneficial predatory mites. Effective materials include Portal XLO, Oberon, Torac, Agri-Mek, and Movento. Organic growers can use sulfur products (e.g. Microthiol Disperss).

Broad mites were identified in high tunnel peppers in western MA this week. These tiny mites feed in the growing point of pepper plants, causing leaf distortion and russeting on fruit. We most often see broad mite damage in peppers grown in high tunnels. Control is difficult if infestations are only noticed after symptoms appear on fruit, so scouting early for leaf distortion symptoms in young plants is key. Commercially available predatory mites (Neoseiulus/Amblyseius cucumeris and N. californicus) can effectively manage broad mites—release at planting if you have a history of infestations. Mite-specific pesticides can be used but may have negative impacts on beneficial predatory mites. Effective materials include Portal XLO, Oberon, Torac, Agri-Mek, and Movento. Organic growers can use sulfur products (e.g. Microthiol Disperss).

White mold was identified in high tunnel tomatoes in western MA this week, in a tunnel that was known to have a white mold infestation previously. In tomatoes this disease is often referred to as “timber rot”, as entire stems turn papery and tan. White mold, caused by the fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, overwinters as sclerotia—masses of fungal tissue surrounded by a hard black rind—in infected crop residues and soil. The fungus will produce lots of fuzzy white mycelium in and on infected plants, and over time, these sclerotia will develop amongst the mycelium. Infected plants will wilt and die, with the stem turning brown. Crack open the stem to find the mycelium and sclerotia. Removing infected plants will reduce the amount of inoculum in the soil. Don’t compost infected plants. Contans is a commercially available biocontrol product for use against white mold. The material is applied in the fall. The current label for Contans does not include tomatoes, but it includes most other vegetable crops, which are also hosts for the disease, and so can be applied in the fall prior to planting winter greens into a tunnel, and will control white mold in the following summer crop as well.

White mold was identified in high tunnel tomatoes in western MA this week, in a tunnel that was known to have a white mold infestation previously. In tomatoes this disease is often referred to as “timber rot”, as entire stems turn papery and tan. White mold, caused by the fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, overwinters as sclerotia—masses of fungal tissue surrounded by a hard black rind—in infected crop residues and soil. The fungus will produce lots of fuzzy white mycelium in and on infected plants, and over time, these sclerotia will develop amongst the mycelium. Infected plants will wilt and die, with the stem turning brown. Crack open the stem to find the mycelium and sclerotia. Removing infected plants will reduce the amount of inoculum in the soil. Don’t compost infected plants. Contans is a commercially available biocontrol product for use against white mold. The material is applied in the fall. The current label for Contans does not include tomatoes, but it includes most other vegetable crops, which are also hosts for the disease, and so can be applied in the fall prior to planting winter greens into a tunnel, and will control white mold in the following summer crop as well.

Sweet corn

European corn borer: This week, both the NY and IA strains of ECB were caught in Franklin, Hampshire, and Worcester Cos. (see Table 1). Egg laying is happening across the state, and locations along the Connecticut River are in peak flight now and damaged to tassels has been observed in a few fields. Scout now in corn that is whorl-stage and older for egg masses, caterpillars, and feeding damage. Eggs are white and are laid in flat masses on undersides of leaves. Look for small shot holes in leaves, feeding and frass in the tassles, or lodging tassels. When corn begins to silk, the caterpillars will move down the stalks to bore into developing ears. Pesticide treatment is warranted if 12% of ears are infested. See the Sweet Corn Insect Management Field Scouting Guide for instructions on how to efficiently scout a field of corn.

European corn borer: This week, both the NY and IA strains of ECB were caught in Franklin, Hampshire, and Worcester Cos. (see Table 1). Egg laying is happening across the state, and locations along the Connecticut River are in peak flight now and damaged to tassels has been observed in a few fields. Scout now in corn that is whorl-stage and older for egg masses, caterpillars, and feeding damage. Eggs are white and are laid in flat masses on undersides of leaves. Look for small shot holes in leaves, feeding and frass in the tassles, or lodging tassels. When corn begins to silk, the caterpillars will move down the stalks to bore into developing ears. Pesticide treatment is warranted if 12% of ears are infested. See the Sweet Corn Insect Management Field Scouting Guide for instructions on how to efficiently scout a field of corn.

Corn earworm was captured in both Middlesex and Hampshire Cos. this week (see Table 1). CEW did not historically overwinter in New England but instead was blown northward on storm fronts from southern overwintering sites, arriving in New England in late June at earliest. In recent years, it has been showing up in sweet corn in early-June in certain areas of New England, implying that it is overwintering in those locations. CEW moths lay eggs in corn silks and are therefore not a threat to plantings that are not yet silking. Both sites where CEW was captured this week have early corn that was grown on plastic and under row cover and is just beginning to silk now. When a location has silking corn and CEW trap counts exceed 1.4 moths/week (averaged between 2 traps, hence the partial moth), treatment with a pesticide is warranted and spray intervals are determined by trap counts (see Table 2). If corn is not silking and/or CEW trap counts are below 1.4 moths/week, growers should scout for European corn borer to determine if a spray is warranted (see ECB pest alert above).

Corn earworm was captured in both Middlesex and Hampshire Cos. this week (see Table 1). CEW did not historically overwinter in New England but instead was blown northward on storm fronts from southern overwintering sites, arriving in New England in late June at earliest. In recent years, it has been showing up in sweet corn in early-June in certain areas of New England, implying that it is overwintering in those locations. CEW moths lay eggs in corn silks and are therefore not a threat to plantings that are not yet silking. Both sites where CEW was captured this week have early corn that was grown on plastic and under row cover and is just beginning to silk now. When a location has silking corn and CEW trap counts exceed 1.4 moths/week (averaged between 2 traps, hence the partial moth), treatment with a pesticide is warranted and spray intervals are determined by trap counts (see Table 2). If corn is not silking and/or CEW trap counts are below 1.4 moths/week, growers should scout for European corn borer to determine if a spray is warranted (see ECB pest alert above).

| Table 1. GDDs & Sweet corn pest trap captures for week ending June 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest Weather station |

GDD (Base 50°F) |

Trap Location | ECB NY | ECB IA | CEW | CEW SPRay interval |

| Western MA | ||||||

| Chicopee Falls | 562 | Chicopee Falls | - | - | - | - |

| Easthampton | 519 | Hadley | 2 | 0 | 6 | 4 days |

| North Adams | 524 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Richmond | 430 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| South Deerfield | 551 | Whately | 5 | 1 | - | - |

| Westfield Arpt | 565 | Westfield | - | - | - | - |

| Central MA | ||||||

| Leominster | 461 | Leominster | - | - | - | - |

| Lancaster | 14 | 2 |

2 |

6 days | ||

| Northbridge | 470 | North Grafton | - | - | - | - |

| Worcester | 475 | Spencer | - | - | - | - |

| Eastern MA | ||||||

| Bolton | 464 | Bolton | - | - | - | - |

| Stow | 455 | Concord | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Lawrence | 437 | Haverhill | - | - | - | - |

| Ipswich | 423 | Ipswich | - | - | - | - |

| ND | Millis | - | - | - | - | |

| East Bridgewater |

423 |

North Easton | - | - | - | - |

| Sharon | 0 | 0 | - | - | ||

| ND | Sherborn | - | - | - | - | |

| Providence, RI | 444 | Seekonk | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| Swansea | 0 | 0 | - | - | ||

|

ND - no GDD data for this location - no numbers reported for this trap n/a - this site does not trap for this pest |

||||||

| Table 2. corn earworm spray intervals | ||

|---|---|---|

| Moths/Night | Moths/Week | Spray Interval |

| 0 - 0.2 | 0 - 1.4 | no spray |

| 0.2 - 0.5 | 1.4 - 3.5 | 6 days |

| 0.5 - 1 | 3.5 - 7 | 5 days |

| 1 - 13 | 7 - 91 | 4 days |

| Over 13 | Over 91 | 3 days |

Sap beetles were reported in the earliest corn plantings grown on plastic which are now starting to silk. Early sweet corn varieties tend to have poor tip cover, allowing sap beetle adults to lay eggs near the tip, where tiny larvae burrow into the kernels, and make the ears unmarketable. Sap beetles can also be pests of strawberry and other fruits, so they tend to be more of a recurring problem on farms that grow both fruit and corn. Insecticides may be warranted in fields with a previous history of at least 10% ear damage. Research in Maryland showed that ear infestation begins just after silk emerges and that 1 or 2 applications made at 3 and 6-7 days after silking is more effective than later or more applications. Later sprays did not improve control. Insecticides will reduce the number of damaged kernels and ears but will not completely control heavy infestations. Sap beetle adults and larvae are not susceptible to the Bt toxin that is present in Bt corn. Efficacy trials have shown that carbaryl (e.g. Sevin), lambda-cyhalothrin (e.g. Warrior II), bifenthrin (e.g. Bifenture), and methomyl (e.g. Lannate) are more effective than most other insecticides. However, carbaryl cannot be used during the early silk period while corn is shedding pollen and does not allow for hand harvesting after use.

Multiple/Miscellaneous Crops

Tarnished plant bug is active now in New England. TPB will feed on many different crops but in vegetable crops, primarily does damage in lettuce. The bugs feed on the lettuce leaf veins, causing sunken, brown spots. TPB are often most damaging on farms with large swaths of weedy areas bordering fields, as many weeds are hosts for TPB. Thus, controlling vegetation around vegetable fields is key to minimizing TPB damage. Insecticides can be used, though no treatment thresholds have been established in vegetable crops. See the appropriate crop insect control section of the New England Vegetable Management Guide for labeled materials.

Tarnished plant bug is active now in New England. TPB will feed on many different crops but in vegetable crops, primarily does damage in lettuce. The bugs feed on the lettuce leaf veins, causing sunken, brown spots. TPB are often most damaging on farms with large swaths of weedy areas bordering fields, as many weeds are hosts for TPB. Thus, controlling vegetation around vegetable fields is key to minimizing TPB damage. Insecticides can be used, though no treatment thresholds have been established in vegetable crops. See the appropriate crop insect control section of the New England Vegetable Management Guide for labeled materials.

Cut Flower Pest Alerts

Baptisia/False Indigo

Slugs and/or Snails: Slug/snail damage to stems and lower leaves of baptisia was detected in Hampshire Co. Slugs and snails are both members of the mollusk phylum. They are similar in structure and biology, except that slugs lack an external shell. Both need to remain moist to survive, and so are brought out by rainy conditions. They hide in moist areas during the day and feed actively at night, creating ragged holes in stems and leaves. The best way to reduce slug/snail damage is to eliminate places where they can hide during the day, such as weedy patches, boards, debris, stones, and leafy branches close to the ground. Switching from sprinkler to drip irrigation can also help to reduce desirable moist spots. Slugs can also be killed using commercially available baits (e.g. Sluggo). For more information, see this UMass Greenhouse article about slugs, and check out the slug management article in this issue of Vegetable Notes!

Slugs and/or Snails: Slug/snail damage to stems and lower leaves of baptisia was detected in Hampshire Co. Slugs and snails are both members of the mollusk phylum. They are similar in structure and biology, except that slugs lack an external shell. Both need to remain moist to survive, and so are brought out by rainy conditions. They hide in moist areas during the day and feed actively at night, creating ragged holes in stems and leaves. The best way to reduce slug/snail damage is to eliminate places where they can hide during the day, such as weedy patches, boards, debris, stones, and leafy branches close to the ground. Switching from sprinkler to drip irrigation can also help to reduce desirable moist spots. Slugs can also be killed using commercially available baits (e.g. Sluggo). For more information, see this UMass Greenhouse article about slugs, and check out the slug management article in this issue of Vegetable Notes!

Calendula/Pot Marigold

Sooty Mold: Sooty mold was detected on leaves in high tunnel calendula in Hampshire Co. Sooty mold is caused by several genera of slow-growing fungi. They often grow on honeydew produced by phloem-feeding insects like aphids. They are not pathogenic to plants, but may block light to leaves, and can impact the stem’s aesthetic appearance. The most effective way to reduce sooty mold is to control sucking insects, such as aphids.

Sooty Mold: Sooty mold was detected on leaves in high tunnel calendula in Hampshire Co. Sooty mold is caused by several genera of slow-growing fungi. They often grow on honeydew produced by phloem-feeding insects like aphids. They are not pathogenic to plants, but may block light to leaves, and can impact the stem’s aesthetic appearance. The most effective way to reduce sooty mold is to control sucking insects, such as aphids.

Dogwood

Stem and branch cankering caused by  Neofusicoccum: Branch dieback caused by a stem canker pathogen was confirmed in Hampshire Co. on dogwood. There are numerous species of fungi in the genus Neofusicoccum which attack an array of hardwoods and conifers. Symptoms include canopy thinning, foliage browning, and branch dieback. In severe cases, these fungi can girdle stems and branches. Under wet conditions and mild temperatures, spores are blown and splashed from infected areas onto adjacent branches. Insect feeding damage can also create new infection sites. These canker fungi often affect plants that are already stressed by insect damage, winter injury, disease, or drought. The best management strategy is to prune affected branches 6-12 inches below the blighted tissue and remove the diseased material from the site. Repeated scouting and pruning are often necessary. It is difficult to control cankering fungi using fungicides because the pathogen lives beneath the bark and may be present on branches that show no symptoms. Fungicide recommendations are the same as those for Botryosphaeria canker.

Neofusicoccum: Branch dieback caused by a stem canker pathogen was confirmed in Hampshire Co. on dogwood. There are numerous species of fungi in the genus Neofusicoccum which attack an array of hardwoods and conifers. Symptoms include canopy thinning, foliage browning, and branch dieback. In severe cases, these fungi can girdle stems and branches. Under wet conditions and mild temperatures, spores are blown and splashed from infected areas onto adjacent branches. Insect feeding damage can also create new infection sites. These canker fungi often affect plants that are already stressed by insect damage, winter injury, disease, or drought. The best management strategy is to prune affected branches 6-12 inches below the blighted tissue and remove the diseased material from the site. Repeated scouting and pruning are often necessary. It is difficult to control cankering fungi using fungicides because the pathogen lives beneath the bark and may be present on branches that show no symptoms. Fungicide recommendations are the same as those for Botryosphaeria canker.

Ninebark

Aphids: Aphids (ninebark aphids or a related species) were detected on ninebark in Hampshire Co. Depending on the size of the plant, aphids can be sprayed off using a strong jet of water from a hose. Repeated spraying may be necessary. They may also be washed off by heavy rain. If spraying water is not enough, a summer rate of horticultural oil or insecticidal soap can be used.

Aphids: Aphids (ninebark aphids or a related species) were detected on ninebark in Hampshire Co. Depending on the size of the plant, aphids can be sprayed off using a strong jet of water from a hose. Repeated spraying may be necessary. They may also be washed off by heavy rain. If spraying water is not enough, a summer rate of horticultural oil or insecticidal soap can be used.

Powdery Mildew: Powdery mildew was confirmed on ninebark in Hampshire Co. Powdery mildew fungi are ubiquitous in the landscape. There are many species of powdery mildews with different host ranges. Ninebark is susceptible to two powdery mildew species, which can be quite destructive. Both species produce dark-colored fruiting bodies that can cover the surface of infected plant parts. They can result in stunted growth, foliar discoloration, and branch dieback, and can increase susceptibility to other pests/diseases. Powdery mildew infections can ultimately kill the plant. Fungicides can be used but must be applied repeatedly and have limited efficacy. The best management strategy is to replace plants with resistant varieties. Cultivars of P. opulifolius that are known to be resistant to powdery mildew include: 'Nanus' (green foliage), 'Seward', 'Nanus', 'Mono Diablo' (deep purple foliage), and 'Luteus' (yellow foliage).

Contact Us

Contact the UMass Extension Vegetable Program with your farm-related questions, any time of the year. We always do our best to respond to all inquiries.

Vegetable Program: 413-577-3976, umassveg@umass.edu

Staff Directory: https://ag.umass.edu/vegetable/faculty-staff

Home Gardeners: Please contact the UMass GreenInfo Help Line with home gardening and homesteading questions, at greeninfo@umext.umass.edu.

Early Season Weed Management in Carrots

Carrots grow slowly and can be easily overtaken by weeds. For this reason, weed control is critical for carrot production. High weed pressure can result in complete crop loss1. Weeds can also interfere with root shape, which can also reduce marketable yield2. Canopy closure helps reduce weed pressure by blocking light from the soil surface, which slows weed growth and reduces weed germination. Carrots achieve canopy closure slowly and are therefore not very competitive against weeds. This is due to several factors:

Carrots grow slowly and can be easily overtaken by weeds. For this reason, weed control is critical for carrot production. High weed pressure can result in complete crop loss1. Weeds can also interfere with root shape, which can also reduce marketable yield2. Canopy closure helps reduce weed pressure by blocking light from the soil surface, which slows weed growth and reduces weed germination. Carrots achieve canopy closure slowly and are therefore not very competitive against weeds. This is due to several factors:

- Carrots are slow to emerge3

- They have a small canopy width4

- Their emergence is inconsistent3

Critical weed-free period

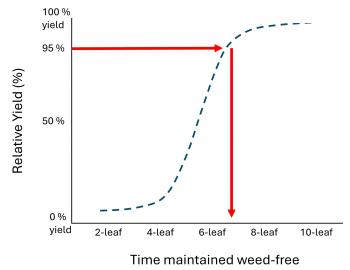

Since carrot growth is slow, early season weed control is critical to help carrots establish and develop their canopy cover. One way to figure out how long you should ideally maintain early season weed control is by determining the critical weed-free period. The critical weed-free period is the length of time after planting that a crop needs to be kept weed-free to maintain an acceptable amount of yield loss from weeds. If, for example, you decide that 5% yield loss from weed pressure is OK, do you need to keep your carrots weed-free until the 2-leaf stage, 4-leaf, 8-leaf, or longer? Weed scientists have done research asking this question, typically setting the acceptable yield loss at 5%, and then using models to figure out when your yields will drop below that threshold (Fig. 1). Researchers in Ontario determined the critical weed-free period for carrots and published their findings in 20101.

Since carrot growth is slow, early season weed control is critical to help carrots establish and develop their canopy cover. One way to figure out how long you should ideally maintain early season weed control is by determining the critical weed-free period. The critical weed-free period is the length of time after planting that a crop needs to be kept weed-free to maintain an acceptable amount of yield loss from weeds. If, for example, you decide that 5% yield loss from weed pressure is OK, do you need to keep your carrots weed-free until the 2-leaf stage, 4-leaf, 8-leaf, or longer? Weed scientists have done research asking this question, typically setting the acceptable yield loss at 5%, and then using models to figure out when your yields will drop below that threshold (Fig. 1). Researchers in Ontario determined the critical weed-free period for carrots and published their findings in 20101.

As with all science, there was variation amongst the sites and amongst the years, but the longest period they needed to maintain a weed-free field to achieve only 5% yield loss was from planting until the 12-leaf stage. The shortest period they needed to maintain a weed-free field was from planting until the 6-leaf stage. These leaf-stages corresponded with maintaining a weed-free period for as long as 808 growing degree days (starting from date of seeding) or as short as just 414 growing degree days.

There are certainly many factors contributing to the wide variation in the length of time needed to maintain a weed-free period. The weed community composition (what weeds are there), the carrot variety, rainfall, and soil type all play a role. But the main driver is planting time. Somewhat counterintuitively, earlier plantings require longer weed-free periods, and later plantings require shorter weed-free periods. In the study from 2010, the field requiring a weed-free period until the 12-leaf stage was planted in late April, but the field requiring a weed-free period until the 6-leaf stage was planted in mid-May. This has been found consistently in similar studies at the University of Wisconsin3,5, and a study at the University of Montana that is currently underway.

What should you do with this information? The recommendation is to concentrate weed management efforts until the 6- to 8-leaf stage, and know that if you are planting earlier, you will need to continue weed control longer to maintain high yields. The earlier you plant, the longer you will need to maintain a weed-free field.

Strategies that emphasize early-season weed control

It’s one thing to know you need to maintain a weed-free period until the 6- to 8-leaf stage, but it’s another to do it. Here are some steps you can take that may help to manage weeds until canopy closure is reached.

- Plant a more competitive variety. There is slight variation in how different carrot varieties are affected by weed pressure. This effect is more pronounced in very weedy fields and is less of an issue in relatively weed-free fields. If you have a field that you know has high weed pressure, one study found that Nelson, Napoli, Spring Market, Red Core, and Bolero maintained their yield better than other varieties3.

- Plant a higher carrot density. In a study at the University of Wisconsin, they explored planting carrots in 5 rows instead of 3 in the same sized bed5. They used the same seeding rate per row across both treatments, so the total amount of seed was 40% higher in the 5-row bed than in the 3-row bed. This led to twice the canopy cover early in the season and a 17-18% yield increase in the 5-row system. This was especially helpful for weed control in carrots planted earlier in the year. This is backed up by research from Brazil, where researchers found that tighter 15-cm row spacing required a shorter critical weed-free period than a wider 20-cm row spacing2.

- Use a pre-plant incorporated herbicide. Pre-plant incorporated herbicides have residual soil activity that help with long early-season weed control. If you use a pre-plant incorporated herbicide, incorporate before making the stale seedbed in order to reduce the amount of weed seeds brought to the soil surface after applying. See the carrot and parsnip weed control section of the New England Vegetable Management Guide for pre-emergent herbicides labeled for carrots. Always read the label before use and follow instructions on the label.

- Use the stale seedbed technique. It is highly recommended that you use this technique to kill as many weeds as you can before planting carrots. See the section on the stale seedbed technique in the New England Vegetable Management Guide for more details or this great article in Vegetable Growers News. This can be done with burn-down herbicides, flaming, or very shallow cultivation using a tool such as a chain harrow or basket weeder.

- Consider doing a blind-spray or blind-flaming. This strategy kills any weeds that have emerged after seeding, but before the crop emerges. It can be a little risky because there is a chance of killing the crop if you time the application incorrectly. There are several strategies to identify the correct timing where carrots have not developed too far when you re-spray or flame your prepared seedbed. These include:

- Digging up several carrot seeds throughout the field to monitor their development.

- Planting radishes in with your carrot seed. The radishes should emerge a little before the carrots, so treat as soon as you see radish emerge.

- Putting down a piece of plexiglass over a small section of row of carrot seed. The plexiglass will warm up the soil faster and cause the carrots to germinate more quickly than carrots in the rest of your field. Re-treat the rest of the field when these have germinated.

- Consider planting a fall cover crop. Fall cover crops would help suppress spring annual weed pressure, which could reduce early-season weeds. There is currently research underway at the University of Montana looking at fall-planted cover crops in carrots. I will be sure to pass along results from that study as soon as it is available.

References

- Swanton, C. J., O’Sullivan, J. & Robinson, D. E. The Critical Weed-Free Period in Carrot. Weed Sci. 58, 229–233 (2010).

- Freitas, F. C. L. et al. Periods of Weed Interference in Carrot in Function of Spacing Between Rows. Planta Daninha 27, 473–480 (2009).

- Colquhoun, J. B., Rittmeyer, R. A. & Heider, D. J. Tolerance and Suppression of Weeds Varies among Carrot Varieties. Weed Technol. 31, 897–902 (2017).

- Turner, S. D., Maurizio, P. L., Valdar, W., Yandell, B. S. & Simon, P. W. Dissecting the Genetic Architecture of Shoot Growth in Carrot (Daucus carota L.) Using a Diallel Mating Design. G3 GenesGenomesGenetics 8, 411–426 (2018).

- Colquhoun, J. B., Rittmeyer, R. A. & Heider, D. J. A holistic carrot production system for season-long weed management. Weed Technol. 34, 876–881 (2020).

--Written by Maria Gannett, Weeds Specialist, UMass Vegetable Program

Recognizing and Managing Slugs in Vegetable Crops

When weather is cool and moist, we see a spike in the number of slug problems on farms. Many growers experiencing slug damage find it difficult to identify which pest is responsible. There are several factors that lead slug damage to be frequently misdiagnosed. They are nocturnal, feeding during the night but seemingly disappearing during the day. The damage they cause also superficially resembles that of other chewing pests such as caterpillars and beetles. Finally, they are not typically considered a major pest capable of causing significant damage on farms. Although they are not usually a concern on larger-scale farms in Massachusetts, slugs may cause significant damage at smaller scales. Fortunately, there are several options for management that are most effective at these smaller scales.

Life Cycle

Slugs overwinter as translucent, light-colored eggs in the soil or other sheltered areas. These eggs hatch in the spring, and juveniles begin feeding on any of a wide range of weeds and crops. Slugs are slimy, soft-bodied invertebrates with two pairs of appendages at the head: one larger pair with eyes and a smaller pair underneath used for identifying odors, similar to the antennae of insects. They are close relatives of snails but are more frequently damaging to crops. Slugs may range in body size from 1/4” to over 4” long depending on age and species. There are many common slug species that may be pests in New England including the gray garden slug, banded slug, marsh slug, and spotted garden slug, but management does not vary considerably between different species. They are typically tan to grayish brown or black and may be patterned with spots or stripes along their body.

Slugs overwinter as translucent, light-colored eggs in the soil or other sheltered areas. These eggs hatch in the spring, and juveniles begin feeding on any of a wide range of weeds and crops. Slugs are slimy, soft-bodied invertebrates with two pairs of appendages at the head: one larger pair with eyes and a smaller pair underneath used for identifying odors, similar to the antennae of insects. They are close relatives of snails but are more frequently damaging to crops. Slugs may range in body size from 1/4” to over 4” long depending on age and species. There are many common slug species that may be pests in New England including the gray garden slug, banded slug, marsh slug, and spotted garden slug, but management does not vary considerably between different species. They are typically tan to grayish brown or black and may be patterned with spots or stripes along their body.

Most slugs reach maturity in 3-6 months. Slugs are hermaphroditic with all individuals capable of laying eggs, which occurs several times per year. Generations overlap and all life stages may be present and feeding through the summer and fall.

Damage

Slugs are generalists, feeding on a wide variety of crops and plant parts including roots, leaves, stems, and fruits. Damage usually appears as large, ragged holes in leaves, but may also include shallow holes in fruits such as tomatoes, peppers, and strawberries. They use their chewing and rasping mouthparts to completely consume large portions of leaves, as opposed to caterpillars which can cause similar feeding damage but avoid consuming leaf veins and stems. Although low to moderate levels of slug damage are not significantly detrimental to plant health, heavy feeding can cause injury and mortality in seedlings and affect development and yield in larger plants, and feeding damage on fruits and leafy greens renders crops unmarketable.

Slugs are generalists, feeding on a wide variety of crops and plant parts including roots, leaves, stems, and fruits. Damage usually appears as large, ragged holes in leaves, but may also include shallow holes in fruits such as tomatoes, peppers, and strawberries. They use their chewing and rasping mouthparts to completely consume large portions of leaves, as opposed to caterpillars which can cause similar feeding damage but avoid consuming leaf veins and stems. Although low to moderate levels of slug damage are not significantly detrimental to plant health, heavy feeding can cause injury and mortality in seedlings and affect development and yield in larger plants, and feeding damage on fruits and leafy greens renders crops unmarketable.

Scouting

Slugs can be difficult to find as they are nocturnal, coming out to feed at night when conditions are cool and damp, then hiding away under weeds, rocks, and debris during the day. Inspect plants for characteristic signs of slug damage as well as shiny trails of mucus, which they leave behind. There are no established thresholds for treatment. Slugs can also be found by scouting at night with a flashlight or by placing large flat objects such as stones or shingles over 6”-deep holes where slugs are suspected to be active. These objects can be lifted up during the day to reveal any slugs which have taken shelter underneath them.

Management

Cultural Controls

- Tillage or similar soil disruption early in the season can destroy slugs and eggs, but farms that have adopted reduced-tillage systems may require other forms of management.

- Avoid moist, shaded habitats near crops. Eliminating weeds can reduce slug habitat.

- Hand picking. At small scales, slugs can be hand-picked with gloves and dropped into soapy water. This should be done early in the morning or after dusk while slugs are most active. Repeat for several days until slug numbers are reduced.

- Beer traps can be used to attract and drown slugs. Bury a container 6” deep in the soil such that the top of the container is flush with the soil’s surface. Fill the container with beer or a mixture of water and yeast to attract slugs, which fall into the liquid and drown. Check, clean, and refill traps as needed every 2-3 days.

- Barriers such as copper tape or foil placed around crops can deter slugs by reacting with their mucus and disrupting their nervous systems. However, these barriers are not always effective and are more practical at small scales where crops can be entirely surrounded. Diatomaceous earth is a powdery substance that can also be used as a pest barrier in some cases. It is sharp on a microscopic scale and can injure many arthropods by cutting their cuticles, but loses efficacy when wet, making it ineffective in the damp conditions preferred by slugs.

Biological Control

Some predaceous beetles such as ground beetles, rove beetles, and firefly larvae are common and regularly feed on slugs and snails as well as other soft-bodied pests. Like slugs, many of these beetles are primarily nocturnal and become more active at night. Although sheltered areas near crops can harbor slugs, once established, these habitats also become populated by naturally occurring predators which can keep slugs at manageable levels. Grassy field boundaries called beetle banks can be created to provide sheltered habitat for these beneficial predators on farms, increasing their numbers. Increased crop diversity, use of cover crops, and reduced use of broad-spectrum insecticides can also help to conserve these natural enemies.

Some predaceous beetles such as ground beetles, rove beetles, and firefly larvae are common and regularly feed on slugs and snails as well as other soft-bodied pests. Like slugs, many of these beetles are primarily nocturnal and become more active at night. Although sheltered areas near crops can harbor slugs, once established, these habitats also become populated by naturally occurring predators which can keep slugs at manageable levels. Grassy field boundaries called beetle banks can be created to provide sheltered habitat for these beneficial predators on farms, increasing their numbers. Increased crop diversity, use of cover crops, and reduced use of broad-spectrum insecticides can also help to conserve these natural enemies.

Chemical Control

Slug baits such as iron phosphate (Sluggo) and metaldehyde (Deadline) pellets cotain substances that harm the digestive system of slugs and snails. Both are applied as soil surface treatments and should not be applied to edible portions of plants. Iron phosphate pellets (Sluggo) are OMRI-listed and effective at small scales but can be costly at large scales. However, iron phosphate is relatively specific in its toxicity to slugs and snails, reducing the impact on natural enemies that can help to control these pests. See the appropriate crop insect control section of the New England Vegetable Management Guide for more information on slug control.

Additional Resources

- Managing Earwigs & Slugs - UMass Extension

- Slugs as Pests of Field Crops - PennState Extension

--Written by Alireza Shokoohi, IPM Specialist, UMass Vegetable Program

Soil Moisture Sensors: A Tool for Smart Irrigation Management Decisions

Understanding the effects of rainfall and irrigation events on soil moisture provides critical insight for growers about the present growing environment for their crops. While experienced growers have learned over seasons of observations how their soils and water interact, utilizing a soil moisture measuring device of some sort enables them to put a number on their observations and more accurately track trends over time.

In 2018, UNH Extension began partnering with eight farms in Merrimack and Belknap counties to install soil moisture sensors in a variety of crops including a high-density apple planting, highbush blueberries, field-grown mixed greens, high tunnel tomatoes, field-grown peppers, and Christmas tree seedlings. Monitoring soil moisture levels on these same farms continued during the 2019 production season, and growers reported that the information they gained as a result of monitoring was very beneficial. Some growers plan to purchase their own set of sensors and accompanying reader once our project concludes.

Grower Feedback

The information that has been gained from a grower’s perspective throughout this project has been quite diverse. There were instances where irrigation cycles were occurring too often and for far longer periods than needed to achieve field capacity of the soil. There were also instances where the use of sensors revealed malfunctioning irrigation system components by reporting unusually dry soil in areas that should have received ample irrigation.

The sensors have allowed growers to more accurately determine the frequency and duration of irrigation events needed, based on soil moisture trends, and maintain adequate moisture for the crops being grown. On many occasions, information from the sensors resulted in growers waiting an extra day or two to irrigate, avoiding unnecessary irrigation. The goal of this project is to provide growers with a useful tool and information resulting in a higher level of water use efficiency. The data collected can be used by growers to help minimize plant stress, disease caused by excess moisture, and improve nutrient uptake. You can begin to see how the readings provided by these sensors can be utilized to fine tune irrigation management strategies and to better manage the growing environment for specific crops.

Sensor Types

The sensors used fall into the category of GMS (Granular Matrix Sensors). This category of sensors provides a reading based on the electrical resistance between two electrodes embedded in the granular matrix within the sensor. The more soil moisture available in the soil, the lower the resistance and the corresponding number on the reader. This resistance reading is reported in kilopascals (kPa) or centibars. Both readings are equal as a resistance measurement. As an example, a reading of 0 would tell us that we have a fully saturated soil, while a reading of 15 would be drier. It helps to think about these numbers in the sense of how hard the plant has to work to pull water from the soil, the higher the number the drier the soil.

The sensors used fall into the category of GMS (Granular Matrix Sensors). This category of sensors provides a reading based on the electrical resistance between two electrodes embedded in the granular matrix within the sensor. The more soil moisture available in the soil, the lower the resistance and the corresponding number on the reader. This resistance reading is reported in kilopascals (kPa) or centibars. Both readings are equal as a resistance measurement. As an example, a reading of 0 would tell us that we have a fully saturated soil, while a reading of 15 would be drier. It helps to think about these numbers in the sense of how hard the plant has to work to pull water from the soil, the higher the number the drier the soil.

Another traditional instrument used to measure soil water tension, the tensiometer, is designed to simulate a plant root and provides the same units of measurement as the GMS sensors described above (we are using the Watermark 200SS). The WATERMARK sensors have been calibrated to provide readings based on the format of soil water tension, defined as the force necessary for plant roots to extract water from the soil. Therefore, the readings from both the tensiometer and WATERMARK sensors are easily comparable.

Installation

Proper installation of the WATERMARK sensors can be accomplished in several ways. Here in New Hampshire, we’ve been closely following the manufacturer’s instructions. Simplified, the standard sensors come with a two-wire lead measuring five feet long. This lead is threaded up through a section of PVC pipe of the desired length depending on your intended sensor depth in the field, glued in place with PVC glue, then capped with another section of larger diameter PVC with a cap and slid over the top to keep moisture out of the tube.

Proper installation of the WATERMARK sensors can be accomplished in several ways. Here in New Hampshire, we’ve been closely following the manufacturer’s instructions. Simplified, the standard sensors come with a two-wire lead measuring five feet long. This lead is threaded up through a section of PVC pipe of the desired length depending on your intended sensor depth in the field, glued in place with PVC glue, then capped with another section of larger diameter PVC with a cap and slid over the top to keep moisture out of the tube.

Before installing the sensor in the field, there is a recommended wetting and drying process that needs to be followed to ensure the sensors quickly responds to changing moisture conditions. Good soil contact with the sensor is essential to ensure accurate readings.

Follow the manufacturer’s instructions to ensure proper installation. Sensors can quickly and easily be moved from one location to another to better understand the dynamics of soil moisture in relation to soil types, irrigation cycles, topographical changes, etc., so long as the installation instructions are followed with each move.

Interpreting the Readings

To take readings using these sensors, growers need access to a digital data reader which simply connects with clips to the end of each wire lead. The cost of these readers is $245 as of June 2024. Each sensor costs $40-44, and a pair of two is recommended for each location. Having two sensors allows growers to better understand the effects of irrigation at varying depths within a planting or block. Sensor depth can be adjusted depending on the rooting depth of the crop.

To take readings using these sensors, growers need access to a digital data reader which simply connects with clips to the end of each wire lead. The cost of these readers is $245 as of June 2024. Each sensor costs $40-44, and a pair of two is recommended for each location. Having two sensors allows growers to better understand the effects of irrigation at varying depths within a planting or block. Sensor depth can be adjusted depending on the rooting depth of the crop.

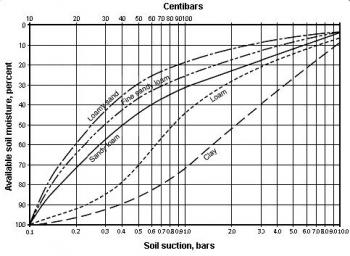

Established recommendations for soil moisture in specific crops and soil types are available. These recommendations provide growers with additional information on which to base their irrigation decisions. In most soils, other than heavy clay, the decision to irrigate would generally happen with sensor readings in the range of 20 to 40 kPa. Differences in soil type should be considered when determining the appropriate range for irrigation. This is because different soil types have varying levels of plant-available water at various soil moisture readings. To clarify, a soil moisture tension reading of 40 kPa in a sandy loam would mean that approximately 50 percent of the water in the soil is available to the plant. Comparatively, a loamy sand soil would have only 35 percent plant-available water at the same 40 kPa reading (see chart). This reinforces the importance of knowing the soil type, along with monitoring soil moisture and visually observing crops and soil to make an informed irrigation decision. Additionally, the method of irrigation should also be considered. For example, it is recommended to begin overhead irrigation when the available soil moisture is no less that 50 percent, while drip irrigation, taking comparatively longer to distribute substantial volumes of water, could be started before the plant-available water drops below 80 percent. Using the sandy loam example from above, this would mean that a reading of 17 kPa would trigger a drip irrigation event.

Editor’s Note: Since this article was written, many growers we work with in MA have adopted these technologies. A lot has also changed, and sensor technology and automation has become more widely available and widely used. We will have a Twilight Meeting in August to demonstrate irrigation sensors and automation and look forward to seeing these systems in action.

--Written by Jeremy DeLisle, UNH Cooperative Extension Fruit & Vegetable Production Field Specialist

Events

Twilight Meeting at Tangerini's Farm - Millis, MA

When: June 12, 2024, 4-7pm - free childcare available!

Where: Tangerini's Spring Street Farm,139 Spring Street, Millis, MA, 02054

Registration: Free! Please register in advance, for food ordering and childcare purposes. Click here to register.

Join Tangerini Farm, the UMass Extension Vegetable Program and SEMAP for a twilight meeting!

- Steve Chiarizio of Tangerini Farm will describe the new tile drainage system and bioreactor that they installed at the farm last year with the help of Massachusetts FSIG funding. A representative from Alleghany Services, who installed the system, will also be on hand to answer questions.

- Maria Gannett, UMass Extension Weed Specialist, and Sue Scheufele, UMass Extension Vegetable IPM Specialist, will talk about sweet corn weed and insect pest management options.

Presentations 4-6 pm, followed by a light supper.

Program co-sponsored by UMass Extension and the Southeastern Massachusetts Agricultural Partnership (SEMAP)

1 pesticide recertification credit is available for this program.

Field Walk at Brookfield Farm - Amherst, MA

When: Tuesday, June 25, 2024, 4-7pm

Where: Brookfield Farm, 24 Hulst Rd., Amherst, MA 01002

Registration: Free! Please register in advance, for food ordering purposes. Click here to register.

Join Brookfield Farm, the UMass Extension Vegetable Program and NOFA/Mass for a twilight meeting!

- Kerry and Max Taylor from Brookfield Farm will describe the new well they installed last year that includes a solar pump. The well was installed with support from NRCS.

- Sue Scheufele, UMass Extension Vegetable IPM Specialist, will lead a field walk and pest scouting demonstration.

- Maria Gannett, UMass Extension Weed Specialist, will lead a weed walk and discuss weed ID, organic weed management, and the relationship between weeds and soil health.

Presentations 4-6 pm, followed by a light supper.

1 pesticide recertification credit is available for this program.

This event is supported by the Transition to Organic Partnership Program.

Rice in the Northeast Farm School

When: Thursday & Friday, June 27-28, 2024

Where: Boundbook Farm, 276 Burroughs Farm Rd., Vergennes, VT 05491

Registration: $250, plus tent fees for camping. Click here to register.

The 2-day event is an intensive introduction to farming techniques specific to the northeastern United States. Tent camping at the farm is available, but limited to 25 tents. The Farm School registration fee is $250 and tent fees are additional. Registration is limited to 75 attendees.

- How to Farm Rice: Learn how to start a rice farm with rice varieties and technology adapted to the Northeastern U.S climate, growing conditions, and farming landscape. Learn about field preparation, duck-rice systems, drip-irrigation biomulching, crop varieties, harvesting, processing, and and marketing.

- Camping and Evening Event: On-site, tent camping is available on the farm for two nights. oy the delicious local foods and entertainment on the farm, including live music, a bonfire, and early morning birdwatching,

- Network with Future Rice Farmers: Farmers and agricultural extension educators across the Northeast are improving ways to farm rice ecologically. Now is the time to create a Northeastern rice cooperative. Be part of the founding NE farmers and educators to advance peer-to-peer learning.

Field Walk at Hannan Healthy Foods - Lincoln, MA

When: Wednesday, July 3, 2024, 4-6pm

Where: Hannan Healthy Foods, 270 South Great Rd., Lincoln, MA 01773. Park in the lot by the farm stand, carpool if possible as space is limited and the stand will be open to customers at this time.

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

Join Eastern MA CRAFT, UMass Extension, and NOFA/Mass for a pest walk at Hannan Healthy Foods in Lincoln, MA! We will discuss how to identify and monitor some of the most prolific and problematic pests and diseases ubiquitous to organic production. Scouting and identification are the first steps towards proactive mitigation practices, learn how to see the farm with fresh eyes.

2 pesticide recertification credits are available for this program.

This event is supported by the Transition to Organic Partnership Program.

Field Walk at Astarte Farm - Hadley, MA

When: Tuesday, July 9, 2024, 4-6pm followed by a light meal

Where: Astarte Farm, 123 West St., Hadley, MA 01035

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

Join Astarte Farm, the UMass Extension Vegetable Program and NOFA/Mass for a twilight meeting!

- Ellen and Dan from Astarte Farm will lead a tour of the farm, highlighting pollinator habitat that they've installed. The habitat was installed with funding from NRCS.

- Hannah Whitehead, UMass Extension Educator, will talk about the benefits of pollinator habitat for organic farmers.

- Sarah Berquist, UMass Lecturer and cut flower farmer, will discuss the flowers that she grows at Astarte.

1 pesticide recertification credit is available for this program.

This event is supported by and MDAR Specialty Crop Grant and the Transition to Organic Partnership Program.

Field Walk at Morning Glory Farm - Edgartown MA

When: Wednesday, July 17, 2024, 6-8pm

Where: Morning Glory Farm, Edgartown, MA

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

Join UMass Extension specialists Sue Scheufele and Maria Gannett for a field walk at Morning Glory Farm. We will identify current pest and weed issues in vegetable crops and discuss their management. There will be lots of time for Q&A, discussion, and dinner and refreshments will be provided.

2 pesticide recertification credits are available for this program.

This event is co-sponsored by NOFA/Mass and Martha’s Vineyard Ag Society with support from the Transition to Organic Partnership Program.

Water & Climate Change Twilight Meeting at Bardwell Farm – Hatfield, MA

When: Friday, August 2, 2024, 5-7pm, with dinner and discussion to follow

Where: Bardwell Farm, 49 Main St., Hatfield, MA 01038

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

Join UMass Extension and CISA for a climate-themed twilight meeting at Bardwell Farm in Hatfield, MA!

- Lisa McKeag will share findings from her recent water quality survey of farms around MA and discuss potential risks and impacts of weather and climate change and rising year-round temperatures on agricultural water quality.

- Harrison Bardwell will show off his new automated irrigation system, and discuss irrigation practices and funded projects around the farm.

- Sue Scheufele will discuss increasing pest risks caused by a hotter climate on vegetable pests including an on-farm trial for managing Phytophthora blight in peppers hosted by Bardwell Farm.

1 pesticide recertification credit is available for this program.

This event is co-sponsored by CISA as part of their Adapting your Farm to Climate Change Series.

Save the Date! UMass Research Farm Field Day

When: August 13, 2024, time TBD

Where: UMass Crop & Livestock Research & Education Farm, 89 River Rd., South Deerfield, MA

Registration: Coming soon!

Come learn about all the research being done by students and faculty across CNS and by UMass Extension on a tour of the farm. Topics include pollinator habitat, bee health and disease ecology, novel cover cropping strategies, intercropping to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, genetic basis of flowering traits in agriculture, and vegetable variety trials including heat-resistant lettuce varieties for summer production.

Twilight Meeting: Climate Impacts on Weed Management and Soil Health

When: Tuesday, October 8, 2024, 4-6pm, with a light supper to follow

Where: UMass Crop & Livestock Research & Education Farm, 89 River Rd., South Deerfield, MA, 01373

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

How are climate change and hotter temperatures affecting our soils? Often, practices like reducing tillage and cover cropping are recommended to improve soil health, reduce risk of topsoil loss and enhance resilience to drought and flood—practices that can also affect weed management. UMass Extension will discuss general impacts of climate change on soil health and highlight current research on updating recommendations for planting timing and overwintering survival of cover crop species in MA. Maria Gannett, UMass Extension Weeds Specialist, will relate these strategies to how they can impact weed management.

1 pesticide recertification credit is available for this program.

This event is co-sponsored by CISA as part of their Adapting your Farm to Climate Change Series.

New England Vegetable & Fruit Conference - Registration Now Open!

When: Tuesday - Thursday, December 17-19, 2024, 8am-6pm daily

Where: Doubletree Hotel, 700 Elm St., Manchester, NH 03101

Registration: Before November 30, $115/person, or $85 for additional attendees if registering as a group. Students $50. Registration capped at 1,400. Click here to register.

The NEVF Conference includes more than 25 educational sessions over three days, covering major vegetable, berry and tree fruit crops as well as various special topics. A Farmer-to-Farmer meeting after each morning and afternoon session will bring speakers and farmers together for informal, in-depth discussions on certain issues. The extensive trade show has over 120 exhibitors.

Vegetable Notes. Maria Gannett, Genevieve Higgins, Lisa McKeag, Susan Scheufele, Alireza Shokoohi, Hannah Whitehead, co-editors. All photos in this publication are credited to the UMass Extension Vegetable Program unless otherwise noted.

Where trade names or commercial products are used, no company or product endorsement is implied or intended. Always read the label before using any pesticide. The label is the legal document for product use. Disregard any information in this newsletter if it is in conflict with the label.

The University of Massachusetts Extension is an equal opportunity provider and employer, United States Department of Agriculture cooperating. Contact your local Extension office for information on disability accommodations. Contact the State Center Directors Office if you have concerns related to discrimination, 413-545-4800.