To print this issue, either press CTRL/CMD + P or right click on the page and choose Print from the pop-up menu.

Click on images to enlarge.

Crop Conditions

It warmed up a bit out there this week but temperatures are back down again and these cool mornings are really feeling like fall. Potatoes and winter squash are coming out of fields by the truckload. Tomato, eggplant, and pepper ripening is slowing down with the cooler temperatures, but harvests are still continuing for now. Folks are starting to turn over high tunnels to prep for planting winter greens. It can be hard to pull the plug on a high tunnel tomato crop that is still producing, but we have found that winter greens need to be direct-seeded by mid-October in order to produce a significant harvest through the winter. Transplanting greens can buy you a little more time with your summer tunnel crop, though it also adds significant material and labor costs to your winter greens production.

It warmed up a bit out there this week but temperatures are back down again and these cool mornings are really feeling like fall. Potatoes and winter squash are coming out of fields by the truckload. Tomato, eggplant, and pepper ripening is slowing down with the cooler temperatures, but harvests are still continuing for now. Folks are starting to turn over high tunnels to prep for planting winter greens. It can be hard to pull the plug on a high tunnel tomato crop that is still producing, but we have found that winter greens need to be direct-seeded by mid-October in order to produce a significant harvest through the winter. Transplanting greens can buy you a little more time with your summer tunnel crop, though it also adds significant material and labor costs to your winter greens production.

We were sad to learn today that Frank Mangan, retired Extension Professor in the Stockbridge School of Agriculture, passed away a few weeks ago. Frank specialized in ethnic vegetable crop production and worked for many years with immigrant communities throughout Massachusetts to promote the production and sales of culturally significant vegetable crops like jilo and ají dulce peppers. Some of his extensive work can be seen at worldcrops.org and at this page under Recursos de Jardinería. A celebration of life will be held for Frank on Sunday, September 15, at 3pm, in the UMass Campus Center Marriot Center, 11th floor.

Brassicas

Black rot is widespread in some fall brassica plantings now. This disease is caused by a bacterium that infects the vascular system of the plant. It often enters the plant via hydathodes—pores at the end of leaf veins located along the edge of leaves. These infections lead to characteristic V-shaped lesions on the leaf edges. The veins within lesions turn black, giving this disease its name. The bacteria are spread via splashing water and people and equipment moving through fields. To slow spread, work in clean fields first before moving to infected fields. The disease can be seedborne—hot water treatment will eliminate the pathogen from the seed—and can overwinter on infested crop residue. To manage infested crop residue, till under residue promptly after harvest and practice a 3-year rotation out of brassica crops.

Black rot is widespread in some fall brassica plantings now. This disease is caused by a bacterium that infects the vascular system of the plant. It often enters the plant via hydathodes—pores at the end of leaf veins located along the edge of leaves. These infections lead to characteristic V-shaped lesions on the leaf edges. The veins within lesions turn black, giving this disease its name. The bacteria are spread via splashing water and people and equipment moving through fields. To slow spread, work in clean fields first before moving to infected fields. The disease can be seedborne—hot water treatment will eliminate the pathogen from the seed—and can overwinter on infested crop residue. To manage infested crop residue, till under residue promptly after harvest and practice a 3-year rotation out of brassica crops.

Cross-striped cabbageworm (CSCW) infestations are defoliating brassica crops now. Unlike the other brassica caterpillar pests, CSCW eggs are laid in clusters of 3-25 rather than singly, resulting in many caterpillars on a single plant. This often leads to infested plants becoming completely skeletonized. Treatment with an insecticide is warranted if 5% of plants are infested with CSCW. See the cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, and other brassica crops insect control section of the New England Vegetable Management Guide for labeled materials.

Cross-striped cabbageworm (CSCW) infestations are defoliating brassica crops now. Unlike the other brassica caterpillar pests, CSCW eggs are laid in clusters of 3-25 rather than singly, resulting in many caterpillars on a single plant. This often leads to infested plants becoming completely skeletonized. Treatment with an insecticide is warranted if 5% of plants are infested with CSCW. See the cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, and other brassica crops insect control section of the New England Vegetable Management Guide for labeled materials.

Cabbage aphid populations are building up now. This pest usually appears mid-summer but populations grow slowly and they mostly become an issue in late-season brassicas. They are easy to identify because they are covered in a white-gray waxy coating that makes them look dusty. They’re most often found in clusters on the undersides of leaves, and the top of the leaf opposite the aphid colony often turns yellow. Heavily infested plants should be rogued out. For successful chemical control of cabbage aphid, treatment must begin early, before infestations become severe. Treat when >10% of plants have at least 1 aphid, or scout 10 leaves at 10 sites in a field (100 leaves total) and treat if >20% have aphids. Use lower thresholds when harvestable portions of the crop have started developing. Effective OMRI-approved materials include azadirachtin, oils, and soaps. M-Pede has not been shown to be effective when used alone, but M-Pede rotated weekly with azadirachtin provided significant control when applied early and regularly. Azadirachtin, horticultural oil, and insecticidal soap can be used together—the combination is more effective than any one alone. Effective conventional products include pyrethroids, organophosphates and neonicotinoids, as well as more selective materials like flonicamid (Beleaf) and pymetrozine (Fulfill). Spirotetramat (Movento), although expensive and not broadly labeled, is a highly effective material with some systemic activity from foliar applications. Use a penetrating surfactant with this material. Fulfill, Beleaf, and Movento all have helpful translaminar or systemic activity. Cyantraniliprole products, which are commonly used for caterpillar control in brassicas, are also fairly effective against aphids in general. Resistance can develop among cabbage populations—rotate between IRAC groups and always follow the label.

Cabbage aphid populations are building up now. This pest usually appears mid-summer but populations grow slowly and they mostly become an issue in late-season brassicas. They are easy to identify because they are covered in a white-gray waxy coating that makes them look dusty. They’re most often found in clusters on the undersides of leaves, and the top of the leaf opposite the aphid colony often turns yellow. Heavily infested plants should be rogued out. For successful chemical control of cabbage aphid, treatment must begin early, before infestations become severe. Treat when >10% of plants have at least 1 aphid, or scout 10 leaves at 10 sites in a field (100 leaves total) and treat if >20% have aphids. Use lower thresholds when harvestable portions of the crop have started developing. Effective OMRI-approved materials include azadirachtin, oils, and soaps. M-Pede has not been shown to be effective when used alone, but M-Pede rotated weekly with azadirachtin provided significant control when applied early and regularly. Azadirachtin, horticultural oil, and insecticidal soap can be used together—the combination is more effective than any one alone. Effective conventional products include pyrethroids, organophosphates and neonicotinoids, as well as more selective materials like flonicamid (Beleaf) and pymetrozine (Fulfill). Spirotetramat (Movento), although expensive and not broadly labeled, is a highly effective material with some systemic activity from foliar applications. Use a penetrating surfactant with this material. Fulfill, Beleaf, and Movento all have helpful translaminar or systemic activity. Cyantraniliprole products, which are commonly used for caterpillar control in brassicas, are also fairly effective against aphids in general. Resistance can develop among cabbage populations—rotate between IRAC groups and always follow the label.

Cucurbits

Powdery mildew (PM) is widespread and severe now in many winter squash and remaining summer squash/zucchini plantings. PM forms powdery white colonies of sporulation on upper and lower leaf surfaces (compared to downy mildew, which forms gray sporulation only on the undersides of leaves). Under heavy disease pressure, leaves turn brown and die back. Once infections are severe, control is unlikely, even with fungicides. There are many powdery mildew-resistant cucurbit varieties available. Control with fungicides involves applying a protectant, broad-spectrum fungicide regularly when conditions become conducive to PM development mid-summer. Once PM begins developing in a crop, a material targeting PM should be added to the spray program. Growers should rotate between at least 2 targeted materials to manage for resistance development. For details and recommended materials, see our Managing Cucurbit Downy and Powdery Mildews article.

Powdery mildew (PM) is widespread and severe now in many winter squash and remaining summer squash/zucchini plantings. PM forms powdery white colonies of sporulation on upper and lower leaf surfaces (compared to downy mildew, which forms gray sporulation only on the undersides of leaves). Under heavy disease pressure, leaves turn brown and die back. Once infections are severe, control is unlikely, even with fungicides. There are many powdery mildew-resistant cucurbit varieties available. Control with fungicides involves applying a protectant, broad-spectrum fungicide regularly when conditions become conducive to PM development mid-summer. Once PM begins developing in a crop, a material targeting PM should be added to the spray program. Growers should rotate between at least 2 targeted materials to manage for resistance development. For details and recommended materials, see our Managing Cucurbit Downy and Powdery Mildews article.

Plectosporium blight is continuing to develop on summer squash and zucchini. This is a fungal disease that causes elongate, white lesions to develop on squash petioles. Under severe disease pressure, the crown of the plant often splits open and becomes colonized by saprophytic bacteria. Plectosporium will also infect fruit, causing round, raised, white lesions. This disease can be controlled with fungicides if applied early and often. Labeled materials include Aprovia Top, Inspire Super, and the strobilurin (FRAC Group 11) fungicides Quadris Top, Merivon, Cabrio, and Flint. The Group 11 fungicides are effective but there is significant risk of the pathogen developing resistance to them, so any application of a Group11 fungicide should be followed with an application of a protectant fungicide (e.g. chlorothalonil, mancozeb).

Plectosporium blight is continuing to develop on summer squash and zucchini. This is a fungal disease that causes elongate, white lesions to develop on squash petioles. Under severe disease pressure, the crown of the plant often splits open and becomes colonized by saprophytic bacteria. Plectosporium will also infect fruit, causing round, raised, white lesions. This disease can be controlled with fungicides if applied early and often. Labeled materials include Aprovia Top, Inspire Super, and the strobilurin (FRAC Group 11) fungicides Quadris Top, Merivon, Cabrio, and Flint. The Group 11 fungicides are effective but there is significant risk of the pathogen developing resistance to them, so any application of a Group11 fungicide should be followed with an application of a protectant fungicide (e.g. chlorothalonil, mancozeb).

Squash vine borer (SVB) trap counts (Table 1) are continuing to rise, with some locations back above threshold for insecticide application. The larvae that will result from this flight may bore into winter squash fruit, making them unmarketable and allowing for entry of secondary pathogens.

|

table 1. Squash Vine borer Pheromone Trap captures for week ending August 29

|

|

|---|---|

|

Trap location

|

SVB

|

|

Whately

|

1 |

|

North Easton

|

4 |

| Sharon | 18 |

|

Westhampton

|

0 |

|

Spray thresholds: Thick-stemmed cucurbits only. 5 moths/week for bush-type cucurbits. 12 moths/week for vining cucurbits.

|

|

Ginger

Root rot has been diagnosed in several ginger crops, causing leaf yellowing and plant stunting. In one case, the pathogens Fusarium, Pythium, Phytophthora, and Rhizoctonia were all cultured out of the diseased rhizomes. Of these genera, Phytophthora is the most aggressive, but it is not clear which pathogen may have initially caused disease and which may be secondary. Fusarium and Rhizoctonia are found in most soils and usually only cause disease when plants are otherwise compromised.

Lettuce

Nightshades

Anthracnose is developing in tomato fruit. Anthracnose is a fungal disease that causes round, sunken lesions on tomato and pepper fruit. The lesions eventually develop concentric rings of dark fungal fruiting bodies, giving them a fuzzy black appearance. This disease affects ripe fruit only, and we most commonly see it in crops that are being underharvested. Harvest thoroughly to reduce inoculum, then practice at least a 1-year crop rotation out of solanaceous crops. This fungus can be carried on seed—hot water seed treatment can effectively eliminate the pathogen from the seed.

Anthracnose is developing in tomato fruit. Anthracnose is a fungal disease that causes round, sunken lesions on tomato and pepper fruit. The lesions eventually develop concentric rings of dark fungal fruiting bodies, giving them a fuzzy black appearance. This disease affects ripe fruit only, and we most commonly see it in crops that are being underharvested. Harvest thoroughly to reduce inoculum, then practice at least a 1-year crop rotation out of solanaceous crops. This fungus can be carried on seed—hot water seed treatment can effectively eliminate the pathogen from the seed.

Stemphylium or gray leaf spot is widespread on several farms that we’ve visited this year. This is a relatively new fungal disease of tomato in the Northeast. The pathogen forms brown leaf spots that develop a gray appearance when the fungus produces spores. It can look very similar to Septoria leaf spot. See our Gray Leaf Spot on Tomato article and the Tomato Disease Control section of the New England Vegetable Management Guide for more information.

Late blight was diagnosed in a high tunnel tomato crop in Vermont this week, in addition to the field crop near Burlington earlier in the week. Growers with tomato crops that are still relatively healthy and free of other diseases, who expect to get significant yields from the crop in September, should protect their crop with fungicides now if you’re not already. Some strains of late blight are resistant to the fungicide mefenoxam (e.g. Ridomil Gold Bravo, Ridomil Gold Copper, and Ridomil Gold MZ WG). The strain present in VT has not yet been identified but the strains next-closest to us were both identified as US-23, which is sensitive to mefenoxam, meaning the Ridomil fungicides will be effective against the pathogen. Other effective fungicides include Previcur Flex and Presidio SC (both systemic); Revus Top, Forum, and Tanos (all translaminar); and Quadris Opti, Quadris Top, and Cabrio (less effective than the previous materials). Ranman, Gavel, and Zoxium, as well as chlorothalonil and mancozeb products, can be used as protectant fungicides against late blight. The most effective OMRI-listed material is copper. Please report any suspected cases of late blight in MA to us at umassveg@umass.edu or 413-577-3976.

Sweet corn

European corn borer (ECB) trap counts remain very low, and caterpillars are being cleaned up well by CEW sprays.

Corn earworm (CEW) trap counts are low this week, with the exception of a few sites in southeastern MA that normally remain higher than others due to wind patterns blowing moths up the coast. Many farms on a 6-day spray schedule or not requiring a spray at all. If trap counts nearest to you are below 1.4 moths/week, corn should be scouted for ECB and FAW, and treated at a 12% infestation threshold.

Fall armyworm (FAW) trap counts are scattered as always, with a few sites catching some moths and others catching none. If the site nearest you is reporting FAW captures, it is recommended to spray whorl corn, where FAW adults lay eggs.

| Table 2. GDDs & Sweet corn pest trap captures for week ending August 29 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest Weather station |

GDD (Base 50°F) |

Trap Location | ECB NY | ECB IA | FAW | CEW | CEW SPRay interval* |

| Western MA | |||||||

| North Adams | 2216 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Richmond | 2025 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| South Deerfield | 2438 | Whately | 3 | 0 | 10 | 12 | 4 days |

| Chicopee Falls | 2477 | Granby | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | no spray** |

| Granville | 2136 | Southwick | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | no spray** |

| Central MA | |||||||

| Leominster | 2255 | Lancaster | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | no spray** |

| Northbridge | 2280 | Grafton | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | no spray** |

| Worcester | 2279 | Spencer | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | no spray** |

| Eastern MA | |||||||

| Bolton |

2303 |

Bolton | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 days |

| Stow | 2309 | Concord | 0 | 1 | 0 | 18 | 4 days |

| Lawrence | 2362 | Haverhill | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 days |

| Ipswich | 2329 | Ipswich | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | no spray** |

| Harvard | 2299 | Littleton | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 days |

| - | - | Millis | 1 | 1 | n/a | 15 | 4 days |

| Sharon | 2253 | North Easton | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 5 days |

| Sharon | 3 | 1 | n/a | 18 | 4 days | ||

| - | - | Sherborn | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 days |

| Providence, RI | 2352 | Seekonk | 0 | 0 | 4 | 79 | 4 days |

| Swansea | 0 | 0 | 8 | 65 | 4 days | ||

|

ND - no GDD data for this location - no numbers reported for this trap n/a - this site does not trap for this pest * If 2+ days above 80°F occur, shorten spray interval by 1 day. ** If CEW trap captures are below 1.4 moths/week, scout block for ECB and FAW caterpillars and make a pesticide application if 12% of plants in a 50-plant sample are infested. |

|||||||

| Table 3. corn earworm spray intervals | ||

|---|---|---|

| Moths/Night | Moths/Week | Spray Interval |

| 0 - 0.2 | 0 - 1.4 | no spray |

| 0.2 - 0.5 | 1.4 - 3.5 | 6 days |

| 0.5 - 1 | 3.5 - 7 | 5 days |

| 1 - 13 | 7 - 91 | 4 days |

| Over 13 | Over 91 | 3 days |

Miscellaneous Crops

Septoria leaf spot was diagnosed in lettuce this week in Hampden Co. This fungal disease causes blotchy chlorotic spots that become necrotic and brown over time. Spots develop first on lower leaves and move upward in the plant over time. It can look similar to symptoms of lettuce downy mildew, but lettuce downy mildew lesions will develop fuzzy white sporulation on the undersides of leaves. Septoria spores can be carried on seed and the pathogen overwinters on infected crop residues and in wild lettuces. It is a different species than the Septoria that causes the common leaf spot disease in tomato. Seed can be treated with hot water to eliminate Septoria. Till under infected crop residues promptly after harvest to hasten decomposition, and practice crop rotations out of Asteraceae family crops.

Septoria leaf spot was diagnosed in lettuce this week in Hampden Co. This fungal disease causes blotchy chlorotic spots that become necrotic and brown over time. Spots develop first on lower leaves and move upward in the plant over time. It can look similar to symptoms of lettuce downy mildew, but lettuce downy mildew lesions will develop fuzzy white sporulation on the undersides of leaves. Septoria spores can be carried on seed and the pathogen overwinters on infected crop residues and in wild lettuces. It is a different species than the Septoria that causes the common leaf spot disease in tomato. Seed can be treated with hot water to eliminate Septoria. Till under infected crop residues promptly after harvest to hasten decomposition, and practice crop rotations out of Asteraceae family crops.

Fusarium wilt was diagnosed in 'Prospera' basil this week. Fusarium is a soil-borne fungus that infects the vascular system of the plant. There are many species of Fusarium and the fungus is ubiquitous in the soil, but the strain that infects basil (Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. basilicum) is aggressive. Infected plants become stunted, stems develop brown lesions starting at the soil line, and leaves will wilt and then drop. Fusarium will survive in the soil for several years, so fields that develop infection should be rotated out of crops in the mint family for 3 years. There are resistant varieties of basil that will hold up against the disease for some time.

Fusarium wilt was diagnosed in 'Prospera' basil this week. Fusarium is a soil-borne fungus that infects the vascular system of the plant. There are many species of Fusarium and the fungus is ubiquitous in the soil, but the strain that infects basil (Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. basilicum) is aggressive. Infected plants become stunted, stems develop brown lesions starting at the soil line, and leaves will wilt and then drop. Fusarium will survive in the soil for several years, so fields that develop infection should be rotated out of crops in the mint family for 3 years. There are resistant varieties of basil that will hold up against the disease for some time.

Contact Us

Contact the UMass Extension Vegetable Program with your farm-related questions, any time of the year. We always do our best to respond to all inquiries.

Vegetable Program: 413-577-3976, umassveg@umass.edu

Staff Directory: https://ag.umass.edu/vegetable/faculty-staff

Home Gardeners: Please contact the UMass GreenInfo Help Line with home gardening and homesteading questions, at greeninfo@umext.umass.edu.

Pumpkin & Winter Squash Harvest, Curing & Storage

Pumpkins and winter squash—at least those that didn’t succumb to Phytophthora blight or other diseases—are being harvested now. Correct harvest timing, curing, and storage conditions can significantly affect eating quality, storage length and postharvest disease.

Harvest

Despite their tough appearance, squash and pumpkin fruit are easily damaged. It is important to avoid bruising or cutting the skin during harvest. Once the rind is bruised or punctured, decay organisms will invade the fruit and quickly break it down. Place fruit gently in containers and move bins on pallets. Use gloves to protect both the fruit and the workers. For some squash, especially butternut, stems can be removed to prevent them from puncturing adjacent fruit during harvest and storage. If stems are removed, allow the stem scars to heal before putting into storage (see Curing below).

Harvest Timing for Winter Squash and Pie Pumpkins

For winter squash and pie pumpkins, harvest timing determines the flavor and texture of the fruit. As squash fruits grow, they accumulate starch, which is then converted into sugar in the field and during storage. The balance of starch (texture) and sugar (sweetness) in a squash determines the eating quality. Squash is mature when seeds are completely filled. If squash is harvested before it is mature, the fruit will use starch reserves from the flesh to fill the seeds, resulting in poor flesh quality. Immature squash will also not have enough starch to convert into sugar later on.

Most squash varieties are mature and ready to harvest 50-55 days after fruit set, or days after pollination (DAP). In many varieties, this is many weeks after the fruit turns a marketable color, which can be misleading. Dr. Brent Loy, late researcher emeritus at the NH Ag Experiment Station, said that days to maturity listed in seed catalogs are often incorrect, especially for acorn squash; catalogs often state 70-76 days to maturity (from time of seeding) when in reality it’s more like 90-100 days to maturity. It’s not necessarily easy to keep track of fruit set, so there are some other indicators that squash is ready for harvest—see the end of this article for information specific to different squash types.

Harvest Timing for Halloween Pumpkins

Since the pumpkin market lasts from Labor Day to Halloween, pumpkins may need to be held for several weeks before they can be sold. One factor in deciding when to harvest is the condition of the vines. Intact foliage protects fruit from the sun, and when vines and foliage die down from powdery or downy mildew, fruit can get sunscald. Foliar diseases, especially powdery mildew, can also reduce the quality of pumpkin handles, leading to reduced marketability for jack-o-lantern pumpkins. As cooler fall weather approaches, the other major factor in deciding when to harvest is avoiding chilling injury. Chilling hours accumulate when squash or pumpkins are exposed to temperatures below 50°F in the field or in storage. Injury increases as temperature decreases and/or length of chilling time increases. This is particularly important for squash headed into long-term storage.

There can be extra work involved in bringing fruit in early and finding good storage locations, especially for growers who normally have pick-your-own harvest. Ideally, pumpkins would be harvested as soon as crops are mature and stored under proper conditions. Proper curing and storage conditions are key for Halloween pumpkins in particular, because improper conditions can result in handles shrinking and shriveling, making the pumpkins unmarketable. If you need to hold fruit in the field for pick-your-own or any other reason, using a protectant fungicide (e.g. sulfur, oil, or chlorothalonil) along with one of the targeted powdery mildew products can help protect from black rot, powdery mildew, and other fungal fruit rots. Recommended materials can be found in our Managing Cucurbit Downy and Powdery Mildews article. For information on identifying and controlling fungal fruit rots of winter squash, see our Fruit Rots of Pumpkin and Winter Squash article. Insect pests may include squash bug nymphs and adults and striped cucumber beetles. Scout for insects feeding on the fruit and handles and control if damage is evident. See the Pumpkin, Squash, & Gourds insect control section of the New England Vegetable Management Guide for pesticide recommendations.

Curing

For some squash types (e.g. acorn and delicata), the mature fruit can be eaten immediately after harvest. Other squash types (e.g. butternut, hubbard, kabocha), need time to convert starches to sugars and must be cured or stored for a specific amount of time before they are eaten.

For some squash types (e.g. acorn and delicata), the mature fruit can be eaten immediately after harvest. Other squash types (e.g. butternut, hubbard, kabocha), need time to convert starches to sugars and must be cured or stored for a specific amount of time before they are eaten.

Curing speeds up the conversion of starches to sugars so that squashes reach optimum eating quality sooner. It also causes fruit skin to harden and accelerates wound healing to prevent disease development. Cucurbita maxima and moschata squash varieties can be cured to hasten market readiness. However, curing is not always necessary: if you are planning to store squash for a few months before selling, and the fruit is free of wounds, it should have sufficient time to convert starches to sugars and can go directly into storage conditions without the extra boost. Cucurbita pepo squash types are ready to eat at harvest (if harvested when mature!) and curing can actually reduce their storage lifespan.

To cure squash, store it for a short period of time (5-10 days) at a high temperature (80-85°F) and 80-85% relative humidity immediately after harvest. This can take place in the field if weather allows (night temperatures should not drop below 60°F), or in a well-ventilated barn, greenhouse, or high tunnel.

Storage

Pumpkins and winter squash should be stored in a cool, dry, well-ventilated area. Store fruit at 50-60°F with 50-70% relative humidity. Chilling injury is possible at temperatures below 50°F, and long-term storage at temperatures above 60°F will result in weight loss due to increased respiration rates. Large fluctuations in temperature favor condensation on fruit within the bin, which encourages disease. Therefore, fruit temperature should be kept as close to the temperature of the air as possible to avoid condensation and fruit rot. Relative humidity above 70% provides a favorable environment for fungal and bacterial decay organisms, and relative humidity below 50% can cause dehydration and weight loss. In a greenhouse, temperature can be managed with ventilation on sunny days; heaters will be needed for storage into November and beyond. An inner curtain can reduce heat loss and cost.

Storage life depends on the condition of the crop when it comes in and your ability to provide careful handling and a proper storage environment. All fruit placed in storage should be free of disease, decay, insects, and unhealed wounds. See the end of this article for maximum storage times for different types of squash. Fruit that has been exposed to chilling temperatures (below 50°F) will not store well and should be marketed first.

Few farms have the infrastructure to provide ideal postharvest conditions for all of their fall crops. Fortunately, finding a method that is ‘good enough’ often does the job. Even if it is difficult to provide the ideal conditions, storage in a shady, dry location, with fruit off the ground or the floor, is preferable to leaving fruit out in the field.

Harvest timing and storage needs for different squash types:

Cucurbita pepo (acorn, delicata, sweet dumpling, some pie pumpkins): Acorn squash turns dark green 2-3 weeks after fruit set, which is 40-50 days before it should be harvested. Because acorn squash can be marketed as soon as it turns dark green, regardless of eating quality, many acorn varieties will never accumulate enough starch and will therefore never be sweet. The variety ‘Honey Bear’ was developed by UNH and has high sugar content at harvest. Harvest C. pepo squashes when the ‘ground spot’ (the part of the squash that lays on the ground) is dark orange. Pie pumpkins should be harvested when the skin is fully orange. These varieties can be eaten at harvest and will store for 2-3 months. They should not be cured, because it can reduce their lifespan in storage.

Cucurbita pepo (acorn, delicata, sweet dumpling, some pie pumpkins): Acorn squash turns dark green 2-3 weeks after fruit set, which is 40-50 days before it should be harvested. Because acorn squash can be marketed as soon as it turns dark green, regardless of eating quality, many acorn varieties will never accumulate enough starch and will therefore never be sweet. The variety ‘Honey Bear’ was developed by UNH and has high sugar content at harvest. Harvest C. pepo squashes when the ‘ground spot’ (the part of the squash that lays on the ground) is dark orange. Pie pumpkins should be harvested when the skin is fully orange. These varieties can be eaten at harvest and will store for 2-3 months. They should not be cured, because it can reduce their lifespan in storage.

Cucurbita maxima (kabocha, hubbard, buttercup): Stems become dry and corky when the fruit is ready to be harvested. These are more susceptible than other squash to sunburn and so if vines go down from disease, they should be harvested early (40 DAP), cured, then stored at 70-75⁰F for 10-20 days to achieve acceptable eating quality. These have high starch content at harvest and so need to be stored for 1-2 months before being eaten, with the exception of all mini-kabochas and all red-skinned kabochas, which can be eaten at harvest. They will store for 4-6 months.

Cucurbita moschata (butternut, some edible pumpkins): Butternut will turn tan 45 DAP but should not be harvested for another 2 weeks. Mini-butternut can be eaten at harvest and will store for 3 months. All others should be stored 1-2 months before eating to allow for starches to be converted into sugars and will store for 4-6 months. Carotenoid, the pigment that gives squash its yellow/orange color, also increases in storage for these squash, giving them more color and making them more nutritious.

Additional information:

- Eating Quality in Winter Squash and Edible Pumpkins

- Maximizing Yield and Eating Quality in Winter Squash - A Grower’s Paradox

- Managing Winter Squash for Fruit Quality and Storage

--Written by G. Higgins and R. Hazzard, compiled 2018 from resources by Brent Loy, late researcher emeritus, New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station, and professor emeritus of genetics, UNH.

The Role of Birds in Managing Farm Pests

What do you think of when you hear the term "natural enemy"? Most growers are aware that many insects and spiders are beneficial natural enemies of crop pests, but the contribution of birds to biological control on farms is often overlooked. In fact, birds are more commonly seen as pests rather than beneficial to a farm. However, much like insects, different species of birds can have both positive and negative impacts on farms, and learning about beneficial birds and how to enhance their populations can lead to lower pest pressure and healthier crops.

Pest Management

Many birds are valuable predators of insect pests, and actions taken to enhance the number of these birds on farms can lower crop damage significantly. Insects are the primary food source of more than half of all bird species, and a secondary source for many others. Additionally, most songbirds switch to a predominantly insectivorous diet to feed their young during the nesting season in spring and summer when crops are most susceptible to insect pests.

Many birds are valuable predators of insect pests, and actions taken to enhance the number of these birds on farms can lower crop damage significantly. Insects are the primary food source of more than half of all bird species, and a secondary source for many others. Additionally, most songbirds switch to a predominantly insectivorous diet to feed their young during the nesting season in spring and summer when crops are most susceptible to insect pests.

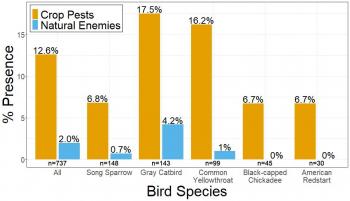

Researchers worldwide have attempted to measure the effect of birds in experiments where crops are surrounded in bird netting, allowing insects to pass through but preventing birds from directly feeding on insects in those crops. These studies frequently reveal more damage on netted crops where birds were excluded, indicating that birds provide significant control of insect pests. A team of UMass researchers found similar results on small-scale fruit and vegetable farms in western Massachusetts in 2019 and 2020. Specifically, they found that birds had a positive impact on cucurbits and brassicas but did not have much impact on solanaceous crops. When birds were excluded from cucurbit crops, the crops had twice as many adult squash bugs, four times as many squash bug nymphs, and almost 70% more damage to leaves. In brassica crops, birds fed mainly on imported cabbageworm and diamondback moth, reducing their numbers by about 35% compared to netted crops. Researchers in this study also analyzed DNA from bird fecal samples collected on farms to determine what types of insects different species of birds were eating and found that Gray Catbirds and Common Yellowthroats were particularly effective pest predators.

It is also important to note that insect-eating birds aren't always beneficial. In eggplant, birds fed on the insect predators which help control Colorado potato beetle, leading to an increase in the pest's numbers. Despite this, leaf damage was lower where birds were present, and DNA from crop pests was found more frequently than that of natural enemies in bird fecal samples, suggesting that the net effect of insectivorous birds is typically positive but depends on the particular crops, insects, and birds involved.

For this reason, identification is an important aspect of managing bird communities, just as it is with insect pests and natural enemies. Binoculars and a bird identification guide can be valuable tools for understanding the species that frequent your farm, making management decisions, and monitoring the success of any strategies put into place. Resources for bird identification also include websites and smartphone apps such as eBird and the Merlin Bird ID app, developed by Cornell University, that can help you identify birds based on photos or audio recordings.

In addition to controlling invertebrate pests, birds of prey such as owls, falcons, and kestrels can also reduce numbers of vertebrate pests such as rodents and pest birds on farms, orchards, and vineyards. Vertebrate pests also tend to avoid areas where predatory birds are present, leading to further reduced numbers.

Supporting beneficial birds on farms

With everything we now know about the services birds provide on farms, there has been demand for farm management strategies to attract beneficial birds. This generally involves providing them with habitat of some kind. The types of habitat surrounding a farm can affect the number and species of birds on the farm. More diverse habitats tend to have resources which can support a greater abundance of birds with a wider array of species, and habitats with more native plants attract more insects, which in turn attract the insectivorous birds which tend to be most beneficial. The presence of windbreaks, hedgerows, and other woody field edges result in greater habitat diversity compared to mowed or weedy patches, with even a few trees or shrubby borders having the potential to attract beneficial birds and deter some pest birds compared to a bare landscape. These habitats can support pest-eating raptors and songbirds including hawks, owls, robins, chickadees, nuthatches, and yellowthroats.

Artificial shelters such as nest boxes and platforms can also be installed on the farm itself to attract many well-known beneficial birds such as owls, kestrels, bluebirds, and chickadees. Different bird species prefer different types of shelters, so the types of birds attracted can be controlled to an extent by the type of shelters used. These should ideally be monitored to ensure they’re not used by pest birds, which should be driven out. Artificial bird shelters can be purchased from various retailers, but they can also be constructed at home. Detailed plans for building nesting structures for many bird species, as well as a tool which suggests species that can be attracted in your area, can be found here.

Finally, with numbers of many native bird species on the decline, it can be helpful just to conserve existing communities of beneficial birds. Preserving existing native and woody habitat surrounding farms can counter habitat loss, a leading cause of avian population decline. Other causes include exposure to certain pesticides such as neonicotinoids, which are toxic to birds and can have severe adverse effects on bird health, behavior, and reproduction. Reducing the use of these materials can benefit bird populations, especially in agricultural areas. Taking steps to reduce habitat for invasive birds such as European Starlings and House Sparrows, which are often also crop pests, can prevent them from competing with native birds. This may involve sealing off access to barns and other large structures on farms which are often used by invasive birds.

Keep in mind that tradeoffs do exist, and there are too many factors to definitively label birds as good or bad for farms. Birds can have negative impacts on crops when insectivorous birds feed on beneficial insects or birds of prey feed on beneficial birds. Many birds also directly lower yield by feeding on crops, and bird feces can contribute to crop contamination and lead to food safety concerns. However, there is evidence that certain management strategies and bird species have net positive impacts towards crop production. For instance, greater amounts of woody habitat seem to encourage more beneficial birds such as the aforementioned Gray Catbirds and Common Yellowthroats while discouraging pest birds which thrive in more open, developed habitats. Pest birds also tend to form large flocks and roosting sites far away from crops and are less likely to take advantage of small woody field borders or nest boxes compared to beneficial birds.

While there is still much to learn about the role of birds on farms, it is a growing area of research with promising implications for integrated pest management. There are several options with varying degrees of investment when it comes to enhancing communities of beneficial birds, and taking the time to determine which strategies will be most beneficial to your particular farm system may lead to significant returns. Taking a broader range of natural enemies into consideration by incorporating birds into integrated pest management plans can result in healthier and more sustainable farm ecosystems, fewer pests, and decreased reliance on pesticides.

Additional Resources

These booklets produced by the Wild Farm Alliance provide extensive information regarding managing communities of beneficial and pest birds.

- Supporting Beneficial Birds and Managing Pest Birds

- Beneficial Bird Habitat Assessment & Native Plant Guide

All About Birds: An online guide to birds that contains information on a wide variety of species.

References

- Garcia, K., Olimpi, E. M., Karp, D. S. & Gonthier, D. J. The Good, the Bad, and the Risky: Can Birds Be Incorporated as Biological Control Agents into Integrated Pest Management Programs? Journal of Integrated Pest Management 11, 11 (2020).

- Mayne, S. J., King, D. I., Andersen, J. C. & Elkinton, J. S. Pest control services on farms vary among bird species on diversified, low-intensity farms. Global Ecology and Conservation 43, e02447 (2023).

- Smith, O. M. et al. Complex landscapes stabilize farm bird communities and their expected ecosystem services. Journal of Applied Ecology 59, 927–941 (2022).

- Supporting Beneficial Birds and Managing Pest Birds. Wild Farm Alliance (2019).

--Written by Ali Shokoohi, UMass Extension IPM Specialist

Preparing for the Fall Flight of the Allium Leafminer

--Written by Ethan Grundberg, Cornel Cooperative Extension. Adapted for Massachusetts growers.

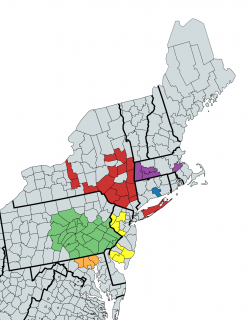

The invasive fly pest, allium leafminer (Phytomyza gymnostoma), has been established in the Northeast since 2016 and has caused crop damage as far north as Washington County, NY, as far east as central Connecticut, and as far west as the Finger Lakes region of NY (see map on next page for reported distribution). In research trials, the fall flight has caused damage to over 98% of leeks that were not covered or managed with insecticides. Now is the time to plan for managing allium leafminer (ALM) in the coming weeks.

The invasive fly pest, allium leafminer (Phytomyza gymnostoma), has been established in the Northeast since 2016 and has caused crop damage as far north as Washington County, NY, as far east as central Connecticut, and as far west as the Finger Lakes region of NY (see map on next page for reported distribution). In research trials, the fall flight has caused damage to over 98% of leeks that were not covered or managed with insecticides. Now is the time to plan for managing allium leafminer (ALM) in the coming weeks.

Life Cycle

Researchers at Penn State have developed a growing degree day model for the spring flight of ALM, but we do not have an accurate model to allow us to predict the emergence of the fall flight. Fall ALM adult activity typically begins in early to-mid-September; we’ve seen a pattern of early pest emergence this summer, so we expect to see ALM in early September this year. Adults are active for approximately 7 weeks, or through the end of October. Emerged adults create the diagnostic line of oviposition puncture marks on allium leaves during feeding and egg-laying. Larvae that hatch from eggs eat their way down the inside of the leaves toward the bulbs, opening up physical wounds where soft rot pathogens often enter. The larvae then pupate either inside the bulb and stem or in the soil around the plants through the winter and early spring. The spring generation typically emerges in mid-April (at 350 GDDs base 1°C starting January 1) and is active for about 5-6 weeks.

Researchers at Penn State have developed a growing degree day model for the spring flight of ALM, but we do not have an accurate model to allow us to predict the emergence of the fall flight. Fall ALM adult activity typically begins in early to-mid-September; we’ve seen a pattern of early pest emergence this summer, so we expect to see ALM in early September this year. Adults are active for approximately 7 weeks, or through the end of October. Emerged adults create the diagnostic line of oviposition puncture marks on allium leaves during feeding and egg-laying. Larvae that hatch from eggs eat their way down the inside of the leaves toward the bulbs, opening up physical wounds where soft rot pathogens often enter. The larvae then pupate either inside the bulb and stem or in the soil around the plants through the winter and early spring. The spring generation typically emerges in mid-April (at 350 GDDs base 1°C starting January 1) and is active for about 5-6 weeks.

Damage

Since there are typically fewer cultivated and wild alliums in the environment in the fall, growers have experienced a “concentration effect” with ALM in their fall-grown alliums, which are mostly leeks. Research trials conducted by Teresa Rusinek and Ethan Grundberg of Cornell Cooperative Extension in the fall of 2020 showed that leeks not treated with insecticides averaged over 40 maggots and pupae per plant, with a high of 160. Much smaller populations of ALM can still be problematic, causing cosmetic damage to scallion foliage and opening physical wounds in leeks where soft rot bacteria can ruin the crop.

Cultural Controls

Growers relying on row cover to exclude adult flies from host crops should install the covers before the flight begins (i.e. this week). Fall allium crops in fields that were infested with ALM in the spring should not be covered, as the flies will emerge under the cover. Field trials funded by Northeast SARE in 2020-21 demonstrated that waiting until two weeks after the fall flight had begun to cover leeks resulted in much higher densities of ALM larvae and pupae in the plants (see more information from the trials here). Growers have had success using insect netting, like Protek-Net, to reduce the risk of heat stress associated with spunbound covers. Both spunbound row cover and insect netting must be well-anchored to prevent gaps between the ground and the crop in order to be effective.

Rusinek and Grundberg have also found that reflective plastic mulch can reduce ALM severity when used in combination with properly timed pesticide applications. In trials, ALM severity was reduced by about 33% in both spring and fall scallions as well as fall leeks when those alliums were planted on reflective plastic mulch compared to either black or white plastic. However, unsprayed fall leeks on reflective mulch in 2019 still had, on average, over 30 ALM maggots and pupae per plant, so using reflective mulch alone does not appear to provide sufficient suppression. Rusinek and Grundberg have found that combining reflective plastic mulch with two carefully timed applications of Entrust with M-Pede (see chemical controls below) has resulted in up to a 92% reduction in the number of ALM maggots and pupae in leeks compared to unsprayed leeks on white plastic mulch.

Chemical Controls

Cornell entomologist Dr. Brian Nault has been conducting insecticide efficacy trials for ALM management since fall 2017. The following conventional insecticides have been found to be the most effective against ALM:

- Scorpion 35 SL (dinotefuran, IRAC Group 4A) has been the most effective at reducing damage from ALM in both NY and PA trials. It is registered for use in all New England states but is not registered for use in New York State. Scorpion is labeled for foliar and soil applications, but foliar applications at 7 fl oz/acre were found to be significantly more effective than drip applications.

- Exirel* (cyantraniliprole, IRAC Group 28). 2(ee) label required for NY growers -- available here: https://www.dec.ny.gov/nyspad/products?3. 13.5 fl oz/acre

- Radiant* (spinetoram, IRAC Group 5) at 8 fl oz/acre

- Warrior II with Zeon Technology (lambda-cyhalothrin, IRAC Group 3A) at 1.6 fl oz/acre

*Growers who have been spraying leeks all summer for onion thrips need to make sure that they have not already reached the maximum annual application rate of Radiant and Exirel (cyantraniliprole, the active ingredient, is also in the pre-mix product Minecto Pro and counts toward maximum active ingredient application rates).

The spray program shown to be most effective for organic growers is:

- 2 consecutive sprays of Entrust (spinosad, IRAG Group 5) at the 6 oz/acre rate, mixed with a 1-5% v/v solution of M-Pede (potassium salts of fatty acids), applied 2-4 weeks after the first detected ALM emergence.

- Plus an application of pyrethrins + azadirachtin (the premix Azera is no longer on the market but PyGanic and one of the many azadirachtin products like Azaguard, Azatrol, or Azatin O can be tank mixed). An adjuvant should be used for the pyrethrins + azadirachtin application that doesn’t increase the spray tank pH above 6.5, which means NOT using M-Pede as the adjuvant in that mix.

As mentioned above, combining the Entrust + M-Pede insecticide applications with reflective plastic mulch provided the largest numeric decrease in ALM maggots and pupae per leek in trials in 2019 (see graph). Pyganic, Surround, and Aza-Direct applied alone did not provide any statistically significant reduction in ALM damage in trials conducted by Dr. Nault. Dr. Nault also compared the efficacy of Entrust with Nu-Film P to the performance of Entrust with M-Pede in at least one of his trials and found that adding Nu-Film, an aggressive sticker, resulted in more allium leafminer damage.

We suspect that the current geographic distribution of ALM in MA is wider than reported, so growers across MA and CT, in the Hudson Valley, and north of the Capital District in NY should be on the lookout for signs of activity. We are recommending that growers thoroughly inspect allium leaves for the linear adult oviposition marks of at least 10 plants on each field edge on a weekly basis beginning the first week of September until activity is observed. If you have any questions about what you are seeing in your fall alliums, please contact your state Extension specialists. For MA growers, the UMass Extension Vegetable Program can be reached at umassveg@umass.edu or (413) 577-3976.

Additional Resources:

- Eastern New York Vegetable News Podcast Allium Leafminer Update

- UMass Pest of the Year Allium Leafminer Presentation

News

2024 Organic Cost Share Reimbursement Application Now Open

Application deadline: December 16, 2024

MDAR is authorized by the USDA – Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) to reimburse certified Organic Crop and Livestock Producers and Handlers (processors) for the Federal 2024 Fiscal Year. Reimbursements are limited to 75% of an operation’s certification costs, up to a maximum of $750 of certification, for the program year. Organic operations certified for crops, wild crops, livestock and handlers are eligible to participate.

Events

EPA Webinar on Draft Strategy to Better Protect Endangered Species from Insecticides

When: Thursday, September 5, 2024, 1-2pm

Where: Online

Registration: Click here to register.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) will hold a public webinar on September 5, 2024, from 1-2 PM ET to provide an overview of its draft Insecticide Strategy. Released on July 25, 2024, the draft strategy furthers the agency’s work to adopt early, practical protections for federally endangered and threatened (listed) species and designated critical habitats from the use of conventional agricultural insecticides.

The draft strategy identifies protections that EPA will consider when it registers a new insecticide or reevaluates an existing one. In developing this draft strategy, EPA identified protections to address potential impacts for more than 850 species listed by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS). The draft strategy identifies protections earlier in the pesticide review process, thus creating a far more efficient approach to evaluate and protect the FWS-listed species that live near these agricultural areas.

The draft insecticide strategy uses the most updated information and processes to determine whether an insecticide will impact a listed species and identify protections to address any impacts. To determine impacts, the draft strategy considers where a species lives, what it needs to reproduce (e.g., food or pollinators), where the pesticide will end up in the environment, and what kind of the pesticide might have if it reaches the species. These refinements greatly reduce the need for pesticide restrictions in situations that do not benefit species.

The webinar will include:

- Discussion of the proposed three-step framework to identify potential population-level impacts to species, identify mitigation measures to address these impacts, and determine the geographic extent of the mitigation measures;

- An overview of case studies to illustrate how the framework could be applied to representative insecticides and how EPA expects to implement the strategy in its registration and registration review actions; and

- An opportunity for the public to ask questions.

The webinar will be open to the public on the GoTo webinar platform, and all interested stakeholders are invited to attend. The agenda and instructions for joining the webinar will be sent to registered attendees.

Save the Date: Urban Agriculture Mentor Farms Fall Twilight Meeting Series

Join the Urban Ag team and Urban Ag Mentor Farms for conversations about our collaborations and technical assistance work this season. We will talk about what we have learned and share farm resources and tips that you can use on your farm this fall and in preparation for next season. More details and registrations coming soon!

Nordica Street Community Farm

When: Thursday, September 19, 4:30-6:30pm

Where: 7 Nordica St., Springfield, MA 01004

Regional Environmental Council

When: Thursday, October 3, 4:30-6:30pm

Where: 42 Lagrange St. (rear), Worcester, MA 01610

Urban Farming Institute

When: Thursday, October 10, 3-5pm

Where: 487 Norfolk St, Mattapan, MA 02126

Dahlia Farm Walk at Grant Family Farm

When: Tuesday, September 24, 4-6pm

Where: Grant Family Farm, 866 Main St, West Newbury, MA

Registration: Free, but please register in advance here.

Join us in West Newbury on September 24 for a farm walk all about dahlias. We’ll tour Grant Family Farm and hear from farmers Alice and Chris. The UMass Extension vegetable program will also host a listening session to learn about your challenges and needs related to growing cut flowers.

Twilight Meeting: Climate Impacts on Weed Management and Soil Health - South Deerfield, MA

When: Tuesday, October 8, 2024, 4-6pm, with a light supper to follow

Where: UMass Crop & Livestock Research & Education Farm, 89 River Rd., South Deerfield, MA, 01373

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

How are climate change and hotter temperatures affecting our soils? Often, practices like reducing tillage and cover cropping are recommended to improve soil health, reduce risk of topsoil loss and enhance resilience to drought and flood—practices that can also affect weed management. UMass Extension will discuss general impacts of climate change on soil health and highlight current research on updating recommendations for planting timing and overwintering survival of cover crop species in MA. Maria Gannett, UMass Extension Weeds Specialist, will relate these strategies to how they can impact weed management.

1 pesticide recertification credit is available for this program.

This event is co-sponsored by CISA as part of their Adapting your Farm to Climate Change Series.

Food Safety & Storage in a Warmer New England

When: Tuesday, October 15, 4-5:30 pm

Where: Kitchen Garden Farm, 131 S. Silver Lane, Sunderland, MA, 01375

Registration: Free, registration info coming soon!

Join UMass Extension, CISA, and UVM Extension for a climate-themed twilight meeting at Kitchen Garden Farm in Sunderland, MA!

- Lilly Israel and Max Traunstein, Owners, Kitchen Garden Farm - Tour of the farm's postharvest and food production facilities, and discussion on how the farm is considering climate change and food safety in its operations.

- Chris Callahan, Extension Associate Professor, UVM Extension Ag Engineering - Precooling resources, sizing CoolBots and coolers, condensation management, and guidance on sorting/culling product for storage

- Lisa McKeag, Extension Educator, UMass Extension - Overview of potential climate impacts on food safety

This event is co-sponsored by CISA as part of their Adapting your Farm to Climate Change series.

Save the Date! Gaining Ground Farm Tour

When: Thursday, October 17, 2024, 4-6pm

Where: Gaining Ground, 341 Virginia Rd., Concord, MA 01742

Join New Entry and UMass Extension for a farm tour of Gaining Ground Farm in Concord, MA!

Registration and event details coming soon.

Vegetable Notes. Maria Gannett, Genevieve Higgins, Lisa McKeag, Susan Scheufele, Alireza Shokoohi, Hannah Whitehead, co-editors. All photos in this publication are credited to the UMass Extension Vegetable Program unless otherwise noted.

Where trade names or commercial products are used, no company or product endorsement is implied or intended. Always read the label before using any pesticide. The label is the legal document for product use. Disregard any information in this newsletter if it is in conflict with the label.

The University of Massachusetts Extension is an equal opportunity provider and employer, United States Department of Agriculture cooperating. Contact your local Extension office for information on disability accommodations. Contact the State Center Directors Office if you have concerns related to discrimination, 413-545-4800.