To print this issue, either press CTRL/CMD + P or right click on the page and choose Print from the pop-up menu.

Click on images to enlarge.

Crop Conditions

Happy October, everyone! We will publish Veg Notes monthly from now through April, with event and news updates as needed in between full issues. Field work is starting to slow down as days become shorter and colder. Some parts of the state have had their first few light frosts, and growers rushed to get sensitive crops in or covered beforehand. Sweet potato and winter squash harvests are wrapping up. We heard from one farmer this week that said they’re happily surprised to still be harvesting some summer squash and zucchini! High tunnel tomatoes are still going, if they haven’t been replaced by winter tunnel crops. We’re nearing the end of the window for seeding winter spinach in high tunnels. Many growers that we’ve heard from in the last few weeks have said that it was overall a good growing season—relatively dry, making disease control easier, reasonable temperatures, good yields, strong markets.

Happy October, everyone! We will publish Veg Notes monthly from now through April, with event and news updates as needed in between full issues. Field work is starting to slow down as days become shorter and colder. Some parts of the state have had their first few light frosts, and growers rushed to get sensitive crops in or covered beforehand. Sweet potato and winter squash harvests are wrapping up. We heard from one farmer this week that said they’re happily surprised to still be harvesting some summer squash and zucchini! High tunnel tomatoes are still going, if they haven’t been replaced by winter tunnel crops. We’re nearing the end of the window for seeding winter spinach in high tunnels. Many growers that we’ve heard from in the last few weeks have said that it was overall a good growing season—relatively dry, making disease control easier, reasonable temperatures, good yields, strong markets.

For a chilly October evening, we had great turnout at the twilight meeting hosted by Kitchen Garden Farm in Sunderland on Tuesday. The program on food safety and storage was part of a climate-related risk management series organized by CISA and UMass Extension. The new owners of Kitchen Garden, Lilly Israel and Max Traunstein, gave an overview of the farm’s operations, discussed some of the challenges they’re dealing with given trends toward increased heat and heavy rain events in the Northeast, and a tour of the facilities they use for the substantial value-added portion of the business. They also talked about some of their strategies for managing risk, including the 800 sq ft freezer that allows them to process and store the tomatoes and onions they use in their salsas and sauces, the back-up generators that will continue to power them in the event of a power outage, and the smart controllers that help to run the equipment more efficiently. They also showed us their dehydrator, filled with racks of peppers and emitting a warm, spicy air—and available for rent by other local farmers to dry down and preserve their crops when the Kitchen Garden isn’t using it (January-August; reach out to them if you’re interested at orders@kitchengardenfarm.org). Thanks to Lilly and Max for hosting, and also to Chris Callahan from UVM Extension, who came down from Vermont to share his expertise—you can find Chris’ long list of storage and other ag engineering-related resources, including a Heating and Cooling Load Calculator for Produce Coolers and Warm Rooms, at his program’s website.

For a chilly October evening, we had great turnout at the twilight meeting hosted by Kitchen Garden Farm in Sunderland on Tuesday. The program on food safety and storage was part of a climate-related risk management series organized by CISA and UMass Extension. The new owners of Kitchen Garden, Lilly Israel and Max Traunstein, gave an overview of the farm’s operations, discussed some of the challenges they’re dealing with given trends toward increased heat and heavy rain events in the Northeast, and a tour of the facilities they use for the substantial value-added portion of the business. They also talked about some of their strategies for managing risk, including the 800 sq ft freezer that allows them to process and store the tomatoes and onions they use in their salsas and sauces, the back-up generators that will continue to power them in the event of a power outage, and the smart controllers that help to run the equipment more efficiently. They also showed us their dehydrator, filled with racks of peppers and emitting a warm, spicy air—and available for rent by other local farmers to dry down and preserve their crops when the Kitchen Garden isn’t using it (January-August; reach out to them if you’re interested at orders@kitchengardenfarm.org). Thanks to Lilly and Max for hosting, and also to Chris Callahan from UVM Extension, who came down from Vermont to share his expertise—you can find Chris’ long list of storage and other ag engineering-related resources, including a Heating and Cooling Load Calculator for Produce Coolers and Warm Rooms, at his program’s website.

Contact Us

Contact the UMass Extension Vegetable Program with your farm-related questions, any time of the year. We always do our best to respond to all inquiries.

Vegetable Program: 413-577-3976, umassveg@umass.edu

Staff Directory: https://ag.umass.edu/vegetable/faculty-staff

Home Gardeners: Please contact the UMass GreenInfo Help Line with home gardening and homesteading questions, at greeninfo@umext.umass.edu.

2024 Pest Trapping Network Summary

Thank you to all of the growers in our sweet corn and squash vine borer trapping network this year, as well as commercial scout, Jim Mussoni! We received trap counts from 18 corn growers and 6 cucurbit growers all season long, and we’re grateful to the growers for checking their traps and reporting to us every week so that we can publish the numbers and management implications in Veg Notes for the rest of you.

Sweet Corn

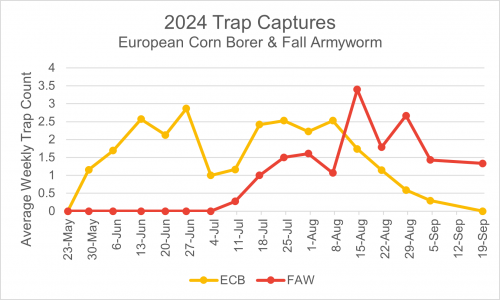

Overall, we captured very few European corn borer (ECB) and fall armyworm (FAW) this summer. This has been the norm for ECB in the past several years, despite the continued presence of ECB caterpillars causing damage in ears. Some trapping locations caught no ECB throughout the entire season, while others caught low numbers with small peaks in early June, and again in mid- to late July.

We saw FAW show up in early July, with numbers remaining below 3 moths/week across the state. However, some farms experienced spikes in July and August. Farms that saw FAW spikes were not in one particular area of the state.

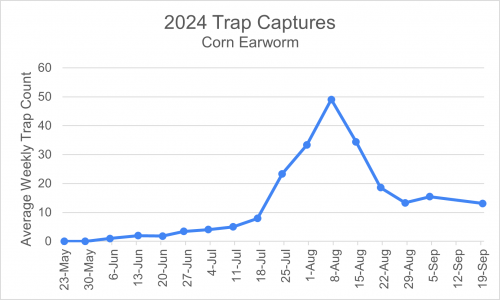

Corn earworm (CEW) showed a very clear trend this year, with trap captures spiking in early August. Captures were high enough to warrant sprays on most farms from mid-July on, and dry weather made it easy to get into fields on-schedule.

Below are graphs of the trap counts from this season, averaged across all the farms. Note the difference in scales—the maximum average CEW trap count was almost 50 moths/week, compared to 3 and 3.5 moths/week for ECB and FAW, respectively.

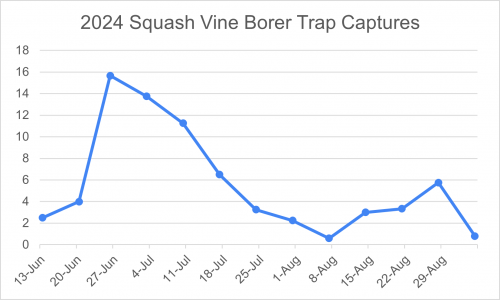

Squash Vine Borer

We saw two flights of SVB this summer—one in late June and another in late August. We didn’t hear any reports of larval damage to winter squash, which can result from a 2nd flight. This pest is highly farm-specific—one farm that traps for SVB caught a high of 36 moths/week while another farm peaked at 8, and many farms don’t see SVB at all. For commercial farms that are struggling with SVB boring into cucurbit stems and would like to manage this pest with pesticide sprays (trapping informs the recommendation to spray or not), we can provide trapping support—reach out at umassveg@umass.edu.

Soil Acidity & Liming: Fall is the Best Time to Lime

As fall progresses and crops come out of fields, many growers will be thinking about applying lime to their fields to raise soil pH or keep it within an optimum range. Lime can be applied in the spring or fall, but fall is often preferred by growers because it allows more time for the lime to react in the soil and fields are often too wet to access in early spring. Most growers test their soil for pH and nutrient levels every few years and apply lime as needed based on those results. For information on taking soil tests, see our Fall Soil Testing article. Soil pH is included in the standard soil test offered by the UMass Soil Testing Lab—see their website for submission forms and instructions.

Soil pH

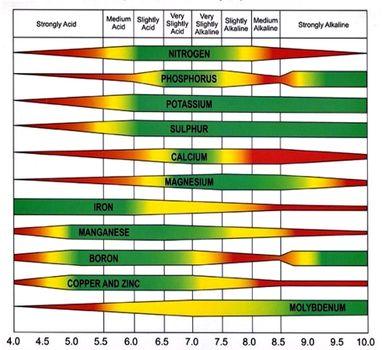

One of the most important aspects of nutrient management is maintaining proper soil pH, which is a measure of soil acidity. A pH of 7.0 is neutral, less than 7.0 is acidic, and greater than 7.0 is alkaline. Most New England soils are naturally acidic and need to be limed periodically to keep the pH in the range of 6.5 to 6.8 desired by most vegetable crops. Scab-susceptible potato varieties are an exception, but even then, some lime may be needed to maintain the recommended pH of 5.0 to 5.2. When the soil is acidic, the availability of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium is reduced, with only 77% of nitrogen and potassium available and 48% of phosphorous available at a pH of 5.5. There are also usually low amounts of calcium and magnesium in acidic soils. Under acidic conditions, some micronutrients are more soluble and are therefore more available to plants; under very acidic conditions, aluminum, iron, and manganese may be so soluble that they reach toxic levels. Soil acidity also influences soil microbes. For example, when soil pH is below 6.0, bacterial activity is reduced and fungal activity increases. Acidic soil conditions also reduce the effectiveness of some soil-applied pesticides.

One of the most important aspects of nutrient management is maintaining proper soil pH, which is a measure of soil acidity. A pH of 7.0 is neutral, less than 7.0 is acidic, and greater than 7.0 is alkaline. Most New England soils are naturally acidic and need to be limed periodically to keep the pH in the range of 6.5 to 6.8 desired by most vegetable crops. Scab-susceptible potato varieties are an exception, but even then, some lime may be needed to maintain the recommended pH of 5.0 to 5.2. When the soil is acidic, the availability of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium is reduced, with only 77% of nitrogen and potassium available and 48% of phosphorous available at a pH of 5.5. There are also usually low amounts of calcium and magnesium in acidic soils. Under acidic conditions, some micronutrients are more soluble and are therefore more available to plants; under very acidic conditions, aluminum, iron, and manganese may be so soluble that they reach toxic levels. Soil acidity also influences soil microbes. For example, when soil pH is below 6.0, bacterial activity is reduced and fungal activity increases. Acidic soil conditions also reduce the effectiveness of some soil-applied pesticides.

Active and reserve soil acidity

To manage soil acidity, growers can apply a basic (compared to acidic) material. The most common and effective material is agricultural limestone, which will be discussed in the next paragraph. To understand how this works, a little background chemistry is helpful. Soil pH is a measure of the free hydrogen ions (H+) in the soil solution, also known as “active acidity”. Additionally, there are positively-charged hydrogen and aluminum ions (H+ and Al3+) bound to negatively charged sites on clay particles and organic matter in soil; these tied-up ions represent “reserve acidity” in the soil. The amount of these binding sites on clay particles and organic matter is referred to as the cation exchange capacity (CEC) of a soil. Soils with more clay or with higher organic matter have a higher CEC than sandier soils or those with lower organic matter. When lime is added to a soil, active acidity is neutralized by chemical reactions that remove free hydrogen ions from the soil solution. Tied-up ions making up the soil’s reserve acidity are then pulled into the soil solution to replace the free hydrogen ions, causing the soil to resist that change in pH. The ability of a soil to resist the change in pH is referred to as a soil’s “buffering capacity”. Clay soils or soils with high organic matter have lots of binding sites for H+ and Al3+ and therefore lots of potential for those ions to be pulled into solution, so these soils are well-buffered compared to sandy soils or soils with low organic matter. To effectively raise the soil pH, both active and reserve acidity must be neutralized. Soil testing labs determine buffering capacity and lime requirement by measuring or estimating the reserve acidity, using a variety of techniques.

Liming materials and calcium carbonate equivalence

There are several materials that can be used to raise soil pH. One of the oldest is wood ash, which is still used by some farmers and gardeners. Today, the most frequently used material is pulverized limestone, also called agricultural lime. Limestone is a common type of sedimentary rock composed of calcium carbonate. It is formed in two ways: oysters, clams, coral, and other ocean-dwelling organisms use calcium carbonate found in seawater to form their shells or other hard surfaces, which accumulate and compress into limestone after they die, or sedimentary ocean water can evaporate to form calcium carbonate deposits. There are two types of agricultural lime available: calcitic lime is almost all calcium carbonate alone and dolomitic lime is calcium carbonate plus magnesium carbonate in roughly equal amounts, which should be used if you also need to add magnesium to your soil.

Different materials and even lime from different sources have different neutralizing capacities. Neutralizing capacity is measured by calcium carbonate equivalence (CCE), where pure calcium carbonate has a CCE of 100; other materials can have a CCE higher or lower than 100. Many liming materials other than pure calcium carbonate contain some level of inert ingredients that will not neutralize soil acidity and therefore have a CCE of less than 100. Liming recommendations made by university soil testing labs are based on a CCE of 100; if your liming material is lower than 100, you will need to apply more than the recommended amount, and if it is higher, you will need less. To determine the amount of liming material to apply, divide the recommended amount by the percent CCE of your material and multiply by 100. For calcitic and dolomitic limes, your supplier can tell you the CCE of the lime you are purchasing. The CCE of wood ash is typically around 50%, but it can vary widely. If purchasing wood ash from a commercial supplier, they should provide a recent analysis. Otherwise, the wood ash should be submitted to a lab offering lime analysis to determine the CCE. Wood ash also contains phosphorous and potassium in varying amounts, which is another good reason to have your wood ash analyzed before applying.

Speed of lime reaction

The speed with which lime reacts in the soil is dependent on particle size and distribution in the soil. Finely ground materials react more quickly than coarse materials. To determine fineness, lime particles are passed through sieves of various mesh sizes. A US Standard 10-mesh sieve has 100 openings per square inch while a 100-mesh sieve has 10,000 openings per square inch. Lime particles that pass through a 100-mesh sieve are very fine and will dissolve and react rapidly (within a few weeks). Coarser material in the 20- to 30-mesh range will react over several years. Agricultural ground limestone contains both coarse and fine particles. About half of a typical ground limestone consists of particles fine enough to react within a few months, but to be certain you can obtain a physical analysis from your supplier. Super fine or pulverized lime is sometimes used for a “quick fix” because all of the particles are fine enough to react rapidly, but these fine materials can be difficult to spread and are usually more expensive than coarser materials. Pelletized lime is also an option; this is pulverized lime that is re-formed into pellets. Pelletized lime reacts more quickly than ground lime and is easier to apply than pulverized lime but is significantly more expensive. Pelletized lime products include ingredients that bind the powdered lime together; some binding products are not OMRI-approved, so be sure to check this if you are a certified organic farm. Because it takes months or years for lime to react in the soil, the timing of liming isn’t a big deal—most growers lime in the fall because it maximizes the reaction time before spring and it’s often easier to access fields in the fall, but whatever lime you apply at whatever time will have an effect in the long run.

The speed with which lime reacts in the soil is dependent on particle size and distribution in the soil. Finely ground materials react more quickly than coarse materials. To determine fineness, lime particles are passed through sieves of various mesh sizes. A US Standard 10-mesh sieve has 100 openings per square inch while a 100-mesh sieve has 10,000 openings per square inch. Lime particles that pass through a 100-mesh sieve are very fine and will dissolve and react rapidly (within a few weeks). Coarser material in the 20- to 30-mesh range will react over several years. Agricultural ground limestone contains both coarse and fine particles. About half of a typical ground limestone consists of particles fine enough to react within a few months, but to be certain you can obtain a physical analysis from your supplier. Super fine or pulverized lime is sometimes used for a “quick fix” because all of the particles are fine enough to react rapidly, but these fine materials can be difficult to spread and are usually more expensive than coarser materials. Pelletized lime is also an option; this is pulverized lime that is re-formed into pellets. Pelletized lime reacts more quickly than ground lime and is easier to apply than pulverized lime but is significantly more expensive. Pelletized lime products include ingredients that bind the powdered lime together; some binding products are not OMRI-approved, so be sure to check this if you are a certified organic farm. Because it takes months or years for lime to react in the soil, the timing of liming isn’t a big deal—most growers lime in the fall because it maximizes the reaction time before spring and it’s often easier to access fields in the fall, but whatever lime you apply at whatever time will have an effect in the long run.

Lime will react most rapidly if it is thoroughly incorporated to achieve intimate contact with soil particles. This is best accomplished when lime is applied to a fairly dry soil and disked in (preferably twice). When spread on damp soil, lime tends to cake up and doesn’t mix well. A moldboard plow has little mixing action; disking is therefore preferred.

Besides neutralizing acidity and raising soil pH, lime is also an important source of Ca and Mg for crop nutrition. It is important to select liming materials based on Ca and Mg soil content with the aim of achieving sufficient levels of each for crop nutrition. If the Mg level is low, a dolomitic lime (high magnesium lime) should be used; if Ca is below optimum, a calcitic (low magnesium lime) should be used. If soil pH is high and Ca is needed, small amounts can be applied as calcium nitrate fertilizer (15% N, 19% Ca), calcium sulfate (aka gypsum, 22% Ca), or superphosphate (14% to 20% Ca).

--Adapted by Genevieve Higgins from the New England Vegetable Management Guide

Culling Garlic: Don't Store or Plant Infected Cloves

There are several opportunities to inspect garlic for symptoms of nematode and disease infection and cull compromised bulbs: during harvest, when crops are going into storage, or as you cut and sort for seed vs. food. At any of these times, we recommend carefully checking and culling garlic in order to prevent disease from spreading through storage and to prevent contaminating another field or next year’s crop by planting infected cloves this fall. Most disease symptoms we see in garlic bulbs result from infections that occurred in the field, and most of the pathogens persist for many years in the soil, so identifying any diseases in your crop now will tell you which fields to avoid planting garlic into in future years. Inspecting your garlic is also very important if you will be selling any garlic as seed; diseases and pests can quickly spread from a single source of infected seed. If you suspect any of the problems below, the UMass Plant Disease Diagnostic Lab can make a positive identification; for submission instructions and contact info visit https://ag.umass.edu/services/plant-diagnostics-laboratory. Below are descriptions of the most common pests and diseases that will affect garlic seed and storage crops.

Bulb Mites

Bulb mites (Aceria tulipae and Rhizoglyphus spp.) are an increasing problem in garlic production across the Northeast. They feed on the garlic roots and basal plate in the field, causing stunting, deformed, yellow leaves, and lack of vigor. In storage, the mites move into the garlic bulb, where their feeding activity causes sunken tan to brown spots on cloves. Feeding activity also provides entry points for secondary pathogens like soft-rot bacteria and fungi. Desiccation may occur. Garlic seed infested with bulb mites may fail to germinate. In the field, plants may outgrow the damage if the infestation is not heavy, but mites may increase in number over the growing season and over years of planting infested seed. Bulb mites can overwinter in the soil, especially in soils with high levels of decaying organic matter, and can survive on the residues of a number of crops. Plant only in fields where crop residue is thoroughly decomposed. Avoid planting alliums directly after corn, grain, or grass cover crops. There has also been some reports from California of bulb mites infesting broccoli; these reports are rare but growers may want to avoid rotating infested garlic to brassicas then back to new, uninfested garlic.

Bulb mites (Aceria tulipae and Rhizoglyphus spp.) are an increasing problem in garlic production across the Northeast. They feed on the garlic roots and basal plate in the field, causing stunting, deformed, yellow leaves, and lack of vigor. In storage, the mites move into the garlic bulb, where their feeding activity causes sunken tan to brown spots on cloves. Feeding activity also provides entry points for secondary pathogens like soft-rot bacteria and fungi. Desiccation may occur. Garlic seed infested with bulb mites may fail to germinate. In the field, plants may outgrow the damage if the infestation is not heavy, but mites may increase in number over the growing season and over years of planting infested seed. Bulb mites can overwinter in the soil, especially in soils with high levels of decaying organic matter, and can survive on the residues of a number of crops. Plant only in fields where crop residue is thoroughly decomposed. Avoid planting alliums directly after corn, grain, or grass cover crops. There has also been some reports from California of bulb mites infesting broccoli; these reports are rare but growers may want to avoid rotating infested garlic to brassicas then back to new, uninfested garlic.

Stem and Bulb/Garlic Bloat Nematode

Stem and bulb, or garlic bloat nematode (Ditylenchus dipsaci) infests garlic stems and bulbs, causing bulb decay at both the neck and the basal plate of the bulbs. This damage can look similar to Fusarium basal plate rot. In the field, plants may be stunted and leaves may be distorted and yellow and may die back prematurely. Bulb tissue begins softening at the neck and gradually proceeds downward; the scales appear pale gray to dark brown, and the bulbs become shrunken, soft, and light in weight. Under moist conditions, secondary invaders such as bacteria, fungi, and onion maggots induce soft rot and decay of the bulbs. The stem and bulb nematode is spread through infested seed, so affected bulbs may still be sold as food, but be clear with customers that the bulbs should not be used as seed. Once this pest is present in a field, it cannot be eradicated.

Stem and bulb, or garlic bloat nematode (Ditylenchus dipsaci) infests garlic stems and bulbs, causing bulb decay at both the neck and the basal plate of the bulbs. This damage can look similar to Fusarium basal plate rot. In the field, plants may be stunted and leaves may be distorted and yellow and may die back prematurely. Bulb tissue begins softening at the neck and gradually proceeds downward; the scales appear pale gray to dark brown, and the bulbs become shrunken, soft, and light in weight. Under moist conditions, secondary invaders such as bacteria, fungi, and onion maggots induce soft rot and decay of the bulbs. The stem and bulb nematode is spread through infested seed, so affected bulbs may still be sold as food, but be clear with customers that the bulbs should not be used as seed. Once this pest is present in a field, it cannot be eradicated.

Downy Mildew

Downy mildew (Peronospora destructor) infects garlic foliage in the field, causing white fuzzy sporulation on the leaves. Infected leaves will turn yellow and die back in storage; affected bulbs may become small and shriveled, with a blackened neck. Outer scales will become water-soaked. Some bulbs may sprout prematurely.

White Rot

Similar to the symptoms of bulb mites and garlic bloat nematode, white rot (Sclerotinia cepivorum) will cause stunting and leaf yellowing and dieback in the field. When infected plants are pulled, white fluffy growth around the stem plate and bulb and small, black, poppy seed-sized sclerotia are visible, often around the neck. Sclerotia are small, dense masses of fungal tissue surrounded by a dark rind that allow the pathogen to persist for years in the soil. White rot sclerotia can survive for 15 years or more in the soil, making this disease one of the hardest diseases of garlic to manage; if you suspect white rot in your garlic, it’s especially important to get it definitively diagnosed so that you don’t introduce it into a new field this fall. This disease will continue to grow and spread in storage if humidity is not kept low.

Similar to the symptoms of bulb mites and garlic bloat nematode, white rot (Sclerotinia cepivorum) will cause stunting and leaf yellowing and dieback in the field. When infected plants are pulled, white fluffy growth around the stem plate and bulb and small, black, poppy seed-sized sclerotia are visible, often around the neck. Sclerotia are small, dense masses of fungal tissue surrounded by a dark rind that allow the pathogen to persist for years in the soil. White rot sclerotia can survive for 15 years or more in the soil, making this disease one of the hardest diseases of garlic to manage; if you suspect white rot in your garlic, it’s especially important to get it definitively diagnosed so that you don’t introduce it into a new field this fall. This disease will continue to grow and spread in storage if humidity is not kept low.

Fusarium Basal Rot

Fusarium basal rot (Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cepae) causes red to purple discoloration of the exterior of the bulb. Sometimes, white fluffy fungal growth at the base is present. If the bulb is cut open, one or several cloves may appear brown and watery. Later, the stem plate becomes pitted and a dry rot develops. The disease continues to develop in storage.

Fusarium basal rot (Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cepae) causes red to purple discoloration of the exterior of the bulb. Sometimes, white fluffy fungal growth at the base is present. If the bulb is cut open, one or several cloves may appear brown and watery. Later, the stem plate becomes pitted and a dry rot develops. The disease continues to develop in storage.

Botrytis Neck and Bulb Rot

Botrytis neck and bulb rot (Botrytis porri and B. allii, respectively) infections start in the fields but symptoms usually do not develop until the bulbs have been moved into storage—a good reason to check your curing garlic periodically! Affected neck or bulb tissue is initially water-soaked, but later turns dry and necrotic. Sclerotia—those hardy black resting structures—form in the neck or adhere to the rotten outer scales of the bulb. Sclerotia of Botrytis are shriveled and look a little like a small raisin; they are much larger than white rot sclerotia, but survive in the soil for fewer years.

Botrytis neck and bulb rot (Botrytis porri and B. allii, respectively) infections start in the fields but symptoms usually do not develop until the bulbs have been moved into storage—a good reason to check your curing garlic periodically! Affected neck or bulb tissue is initially water-soaked, but later turns dry and necrotic. Sclerotia—those hardy black resting structures—form in the neck or adhere to the rotten outer scales of the bulb. Sclerotia of Botrytis are shriveled and look a little like a small raisin; they are much larger than white rot sclerotia, but survive in the soil for fewer years.

Penicillium Decay

Penicillium decay (Penicillium spp.) is a major cause of bulb decay in storage and can spread to healthy bulbs via airborne spores. The fungus causes fuzzy, blue-green growth on diseased cloves, usually starting at the base.

Penicillium decay (Penicillium spp.) is a major cause of bulb decay in storage and can spread to healthy bulbs via airborne spores. The fungus causes fuzzy, blue-green growth on diseased cloves, usually starting at the base.

Keep these symptoms in mind as you pop and plant your garlic this fall to avoid planting affected cloves. Below are some tips for next year to help prevent conditions that allow diseases to spread within your garlic crop.

Disease Prevention Tips for Harvest and Storage:

-

Do not irrigate within 7 days before lifting or harvesting. Avoid harvest after heavy rains.

-

Avoid mechanical injury and bruising of bulbs during production and harvest. Avoid banging cloves together to remove mud and dirt from roots.

- Properly cure bulbs. Cure in a well-ventilated area at 70-80˚F. Practices that hasten curing include undercutting bulbs to sever all roots, avoiding nitrogen fertilization later than two months after seeding, and proper plant spacing. Under wet conditions when bulbs cannot be cured adequately, artificial drying with forced hot air followed by normal storage should be considered.

- For long-term storage, garlic is best maintained at temperatures of 30-32°F with low relative humidity (60- 70%). Good airflow throughout the vented bins or other storage containers is necessary to prevent any moisture accumulation. Under these conditions, garlic can be stored for more than 9 months.

--Written by Susan B. Scheufele, UMass Extension Vegetable Program

News

Information on Joro Spiders

Recent news reports about the large joro spider—introduced to the U.S. from Asia in 2014—have caused some concern, but Joro spiders are nothing to panic about. Despite their large size and venom, they are “shy”, reluctant to bite, and even if they do—the venom is typically weak and not medically important. While the report recently made in Boston seems to be a verifiable report, Joro spiders are currently not widespread throughout Massachusetts. The egg stage is the known overwintering life stage, so adult activity should end with the first hard frost, although these spiders may be a little cold tolerant given their native climate.

Reports: Please report suspicious spiders or those you believe to be a Joro spider, here: https://jorowatch.org/ This will notify the MA Department of Agricultural Resources of your reports as well.

For more information about Joro spiders, please visit:

2024 UMass Garden Calendar Now Available!

UMass Extension works with the citizens of Massachusetts to help you make sound choices about growing, planting, and maintaining plants in our landscapes, including vegetables, backyard fruits, and ornamental plants. Our 2025 calendar continues UMass Extension’s tradition of providing gardeners with useful and practical information. Many people also love the daily tips and find the daily sunrise/sunset times highly useful!

UMass Extension works with the citizens of Massachusetts to help you make sound choices about growing, planting, and maintaining plants in our landscapes, including vegetables, backyard fruits, and ornamental plants. Our 2025 calendar continues UMass Extension’s tradition of providing gardeners with useful and practical information. Many people also love the daily tips and find the daily sunrise/sunset times highly useful!

As always, each month features:

- An inspiring garden image.

- Daily gardening tips for Northeast growing conditions.

- Daily sunrise and sunset times.

- Phases of the moon.

- Plenty of room for notes.

- Low gloss paper for easy writing.

Click here to see the images in this year's calendar, details, and ordering info.

The featured article is Backyard Apple Basics. Apples are among the most common tree fruits and are well-adapted to our local climate. For success in the home orchard, cover the basics! Plant at least two different compatible varieties near each other for cross pollination, fertilize annually to support new shoot growth and prune to promote proper tree structure, and choose resistant varieties to reduce disease problems; consider traps for insect pests.

Our 2025 calendar offers guidelines for proper pollination, effective pruning, how and when to fertilize, and pest management. We also include suggestions for apple varieties suited for the home orchard as well as an update on how planting sunflowers nearby can serve as a trap crop for pests and support for beneficial insects.

COST: $14.50; bulk pricing rates apply to orders of 10 copies or more.

Proceeds from sales of the annual Garden Calendar benefit the work of UMass Extension’s educational programs.

Events

Upcoming Events from the UMass Extension Greenhouse & Floriculture Program

When: Wednesday, November 20, 2024, 8:30am-12pm

Where: Online

Registration: $25/person. Click here to register.

Join the UMass Extension Greenhouse & Floriculture Program for a half-day virtual educational program that will share knowledge and skills useful to close out 2024 on a strong note and look forward to the 2025 season!

Topics:

- In-House Diagnosis of Plant Diseases

- Why Do We Dip Cuttings?

- Importance of Sanitation in Protecting Greenhouse-Grown Crops from Insect and Mite Pests

3 pesticide recertification credits in MA categories 26, 29, 31, and 000 (Applicator’s/Core License) are available for this program.

When: Tuesday, January 14, 2024, 8:30am-12pm

Where: Online

Registration: $25/person. Click here to register.

Topics:

- A New Option for Controlling Plant Growth with Ethephon Drenches

- Identification and Management Strategies for Bacterial and Fungal Leaf Spots on Spring Greenhouse Crops

- How to Optimize Biocontrol Programs to Ensure Successful Pest Management Outcomes

3 pesticide recertification credits for MA categories 26, 29, 31, and 000 (Applicator’s/Core License) are available for this program.

Gracious support from the Massachusetts Flower Growers Association has reduced participation fees for these events as a benefit to the industry.

Questions? Contact Geoffrey Njue, gnjue@umass.edu, 617-243-1932.

New England Vegetable & Fruit Conference - Early bird registration through November 30

When: Tuesday - Thursday, December 17-19, 2024, 8am-6pm daily

Where: Doubletree Hotel, 700 Elm St., Manchester, NH 03101

Registration: Before November 30, $115/person, or $85 for additional attendees if registering as a group. Students $50. Registration capped at 1,400. Click here to register.

The NEVF Conference includes more than 25 educational sessions over three days, covering major vegetable, berry and tree fruit crops as well as various special topics. A Farmer-to-Farmer meeting after each morning and afternoon session will bring speakers and farmers together for informal, in-depth discussions on certain issues. The extensive trade show has over 120 exhibitors.

Vegetable Notes. Maria Gannett, Genevieve Higgins, Lisa McKeag, Susan Scheufele, Alireza Shokoohi, Hannah Whitehead, co-editors. All photos in this publication are credited to the UMass Extension Vegetable Program unless otherwise noted.

Where trade names or commercial products are used, no company or product endorsement is implied or intended. Always read the label before using any pesticide. The label is the legal document for product use. Disregard any information in this newsletter if it is in conflict with the label.

The University of Massachusetts Extension is an equal opportunity provider and employer, United States Department of Agriculture cooperating. Contact your local Extension office for information on disability accommodations. Contact the State Center Directors Office if you have concerns related to discrimination, 413-545-4800.