To print this issue, either press CTRL/CMD + P or right click on the page and choose Print from the pop-up menu.

Click on images to enlarge.

Crop Conditions

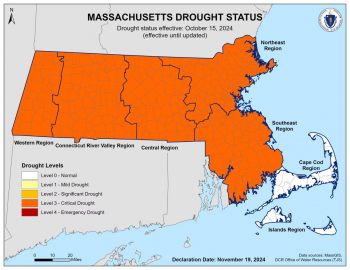

Happy November everyone! It is dry, dry, dry out there, although most of the state is getting some much needed rain today. Fields have been incredibly dusty during final crop cleanups and cover crop seedings, and all parts of the state except for Cape Cod and the islands are officially in a Level 3 Critical Drought, having received 3-4.5 inches less rain than normal for the last 30 days. All regions in drought have seen an 8-11 inch rainfall deficit since August. There is a statewide ban on open burning, in order to stop the unprecedented increase in brush fires across the state.

Happy November everyone! It is dry, dry, dry out there, although most of the state is getting some much needed rain today. Fields have been incredibly dusty during final crop cleanups and cover crop seedings, and all parts of the state except for Cape Cod and the islands are officially in a Level 3 Critical Drought, having received 3-4.5 inches less rain than normal for the last 30 days. All regions in drought have seen an 8-11 inch rainfall deficit since August. There is a statewide ban on open burning, in order to stop the unprecedented increase in brush fires across the state.

Fall farmwork is continuing, with smaller crews busy packing and distributing winter squash, potatoes, sweet potatoes, and root vegetables, and harvesting high tunnel greens (and field greens, in this balmy fall weather!) ahead of Thanksgiving sales and markets.

Here on the Veg Team, we’re gearing up for lots of winter presentations and workshops. The New England Vegetable & Fruit Conference is coming up next month in Manchester, NH and early bird registration pricing ends next Saturday, November 30—register before then to save $30/person. Check out the conference brochure for a list of sessions that will be held over the 3-day conference, as well as a more detailed list of individual talks at each session. Hope we see you there!

Contact Us

Contact the UMass Extension Vegetable Program with your farm-related questions, any time of the year. We always do our best to respond to all inquiries.

Vegetable Program: 413-577-3976, umassveg@umass.edu

Staff Directory: https://ag.umass.edu/vegetable/faculty-staff

Home Gardeners: Please contact the UMass GreenInfo Help Line with home gardening and homesteading questions, at greeninfo@umext.umass.edu.

2024 Vegetable Program Research Highlights

Every year, the UMass Extension Vegetable Program conducts in-field research trials on a variety of vegetable crops, to evaluate pest control and crop management techniques. Our goal is to generate management recommendations that growers can implement immediately on their farms. Below are some highlights from our 2024 trials!

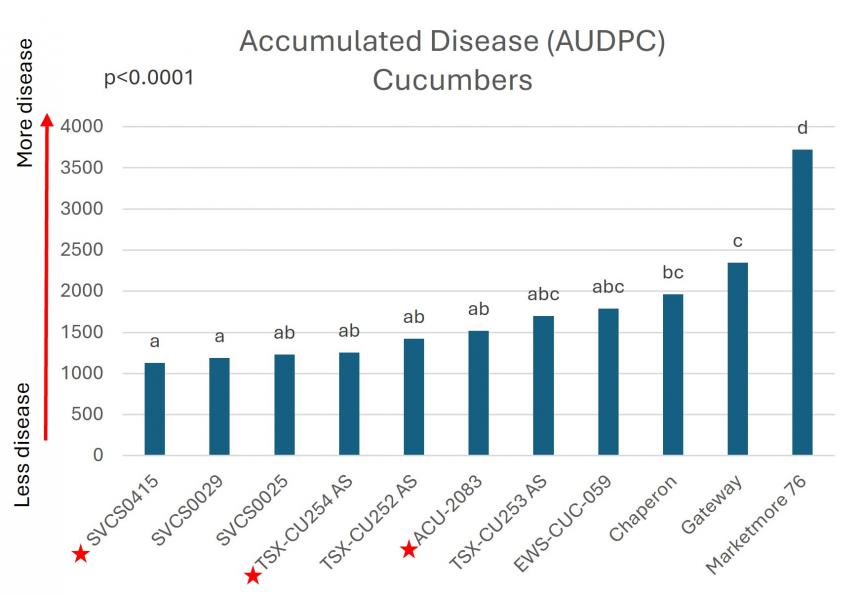

Cucurbit downy mildew in cucumbers

We have been conducting cucurbit downy mildew (CDM) variety trials for many years, helping to evaluate the resistance of new cucumber varieties. This year we trialed 11 varieties and found 3 that were especially good candidates for late summer/fall production, when CDM pressure is high. These varieties, starred in Figure 1, are ‘SVCS0415’, ‘TSX-CU254 AS’, and ‘ACU-2083’—they may be given catchier names down the line if they are chosen to be marketed by distributors. Under the very high disease pressure that we had in our trial, all 3 of those varieties performed better than established CDM-resistant varieties ‘Chaperon’ and ‘Gateway’. 'Chaperon' and 'Gateway' both performed well in previous years, as well as the commercially available DM-resistant varieties 'Bristol', 'Citadel', 'Espirit', and 'DMR401', and are still good choices to include in your crop plans.

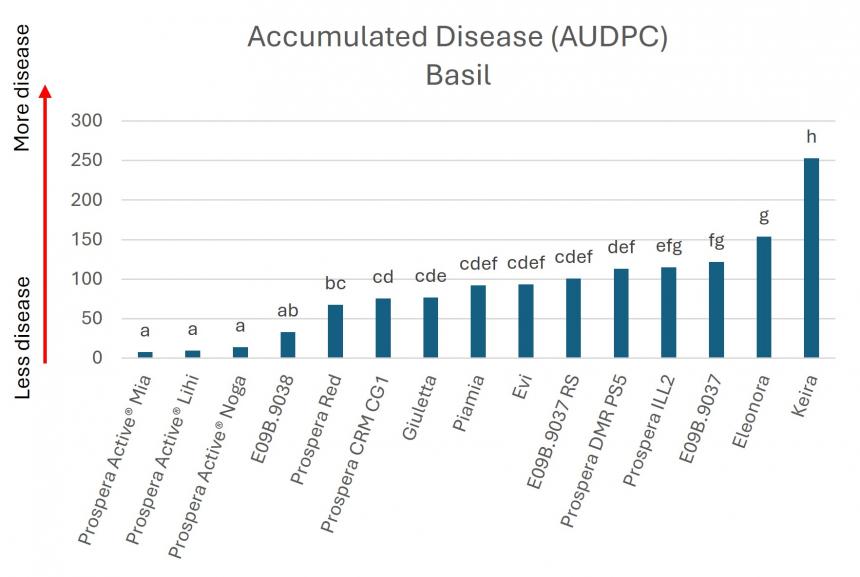

Basil downy mildew

Similarly to the cucurbit downy mildew trials, we have evaluated basil varieties for downy mildew resistance for several years. This year we evaluated 15 varieties, including several unnamed varieties in development, the ‘Prospera’ line, and the new 'Prospera Active' line, which carries a second source of DM resistance in addition to the resistance carried by ‘Prospera’ varieties. The 'Prospera Active' varieties had the lowest levels of downy mildew by far, and did not develop disease until August 27 (2 months after planting and 1 month after downy mildew had first developed in the trial). Under very high disease pressure and when the plants were quite old at the end of the trial, the 'Prospera Active' varieties did eventually develop very low levels of downy mildew, but growers are unlikely to leave plants standing as long as we did.

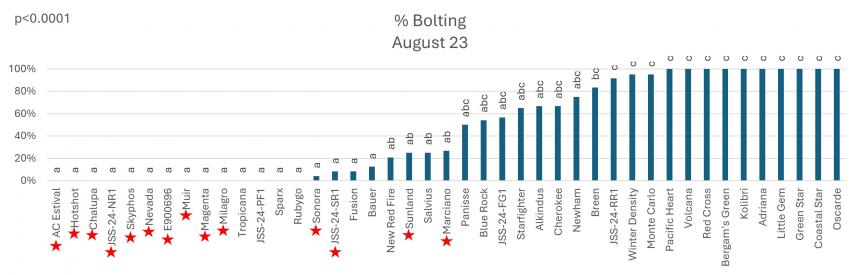

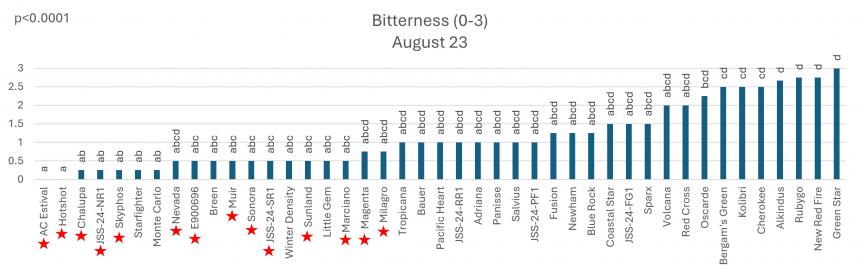

Heat-tolerant lettuce

In an effort to identify heat-tolerant lettuce varieties for summer production, we evaluated 43 (!) varieties of lettuce for heat tolerance, looking at bolting and the development of bitter flavor. Some of the named varieties that performed the best in both categories (starred in Figures 1 and 2) were ‘Muir’ and ‘Nevada’ (green batavias), ‘Milagro’ (green butterhead), ‘Marciano’ and ‘Skyphos’ (red butterheads), ‘AC Estival’ and ‘Hotshot’ (icebergs), ‘Magenta’ (red summercrisp), and ‘Sonora’, ‘Sunland’, and ‘Chalupa’ (romaines). Click on figures to enlarge.

Phytophthora blight in pepper

We evaluated 2 different techniques for Phytophthora blight control in peppers on a commercial farm with a history of the disease-resistant varieties and pesticide soil drenches. The pesticide trial was developed and funded by the IR-4 Project, which is an initiative of the USDA to generate the data necessary for the registration of safe and effective pesticides in specialty crops. We evaluated a few new fungicides and use patterns for efficacy against Phytophthora capsici in pepper, but variability in disease pressure was too high to see treatment differences in our trial. The study was also conducted in Michigan where researchers inoculated the trial, allowing for more uniform disease pressure, and there they showed that a new product ‘YSY’ performed as well as the industry standard. YSY is a biofungicide derived from yeast which is not yet registered—stay tuned! We also evaluated 11 varieties purported to have Phytophthora blight resistance but again had too much variation in disease pressure to draw strong conclustions. Numerically, ‘Tarpon’ had the highest survival rate and very low incidence of canker, and ‘Nitro’ had the lowest incidence of symptoms (stem canker, defoliation, and wilting). These two varieties performed well in all 4 replicate plots, so we can be fairly confident that they would perform as well in other fields and years.

We evaluated 2 different techniques for Phytophthora blight control in peppers on a commercial farm with a history of the disease-resistant varieties and pesticide soil drenches. The pesticide trial was developed and funded by the IR-4 Project, which is an initiative of the USDA to generate the data necessary for the registration of safe and effective pesticides in specialty crops. We evaluated a few new fungicides and use patterns for efficacy against Phytophthora capsici in pepper, but variability in disease pressure was too high to see treatment differences in our trial. The study was also conducted in Michigan where researchers inoculated the trial, allowing for more uniform disease pressure, and there they showed that a new product ‘YSY’ performed as well as the industry standard. YSY is a biofungicide derived from yeast which is not yet registered—stay tuned! We also evaluated 11 varieties purported to have Phytophthora blight resistance but again had too much variation in disease pressure to draw strong conclustions. Numerically, ‘Tarpon’ had the highest survival rate and very low incidence of canker, and ‘Nitro’ had the lowest incidence of symptoms (stem canker, defoliation, and wilting). These two varieties performed well in all 4 replicate plots, so we can be fairly confident that they would perform as well in other fields and years.

Sweet corn corn earworm sentinel plot

We were pleased to participate in a nationwide network of sweet corn sentinel plots this summer, to evaluate the resistance of corn earworm to Bt genes. Bt and non-Bt corn, expressing various combinations of the Cry1Ab, Cry1A.105, Cry2Ab2, and Vip3A resistance genes, were planted, and the number of caterpillars infesting ears of each variety were counted. Nationwide, we are seeing that the Cry genes are becoming less effective against corn earworm, but the Vip3A gene is still effective against corn earworm. We saw this same pattern in our plot this summer, with no caterpillars in ‘Remedy’ (which carries the Cry1Ab and Vip3A genes), an intermediate number of caterpillars in ‘Attribute BC0805’ (Cry1Ab) and ‘Obsession II’ (Cry1A.105 and Cry2Ab2), and lots of caterpillars in the non-Bt varieties ‘Providence’ and ‘Obsession I’.

We were pleased to participate in a nationwide network of sweet corn sentinel plots this summer, to evaluate the resistance of corn earworm to Bt genes. Bt and non-Bt corn, expressing various combinations of the Cry1Ab, Cry1A.105, Cry2Ab2, and Vip3A resistance genes, were planted, and the number of caterpillars infesting ears of each variety were counted. Nationwide, we are seeing that the Cry genes are becoming less effective against corn earworm, but the Vip3A gene is still effective against corn earworm. We saw this same pattern in our plot this summer, with no caterpillars in ‘Remedy’ (which carries the Cry1Ab and Vip3A genes), an intermediate number of caterpillars in ‘Attribute BC0805’ (Cry1Ab) and ‘Obsession II’ (Cry1A.105 and Cry2Ab2), and lots of caterpillars in the non-Bt varieties ‘Providence’ and ‘Obsession I’.

Potato leafhopper

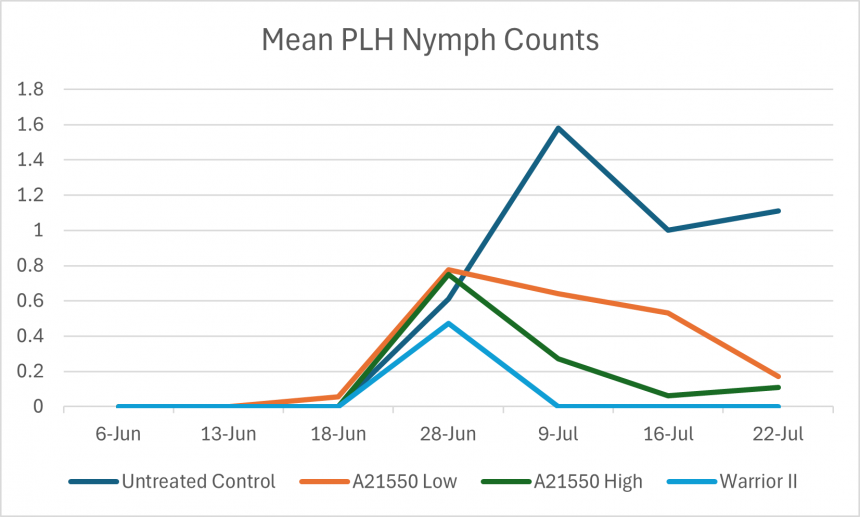

We evaluated a new, yet-unregistered insecticide, Plinazolin, for efficacy against potato leafhopper (PLH) in potato. We assessed how long it took for PLH nymphs to return to treated plots after a single application of the insecticide, and monitored development of hopperburn. Two rates of the trial material were evaluated against an industry standard insecticide, Warrior, and an untreated control. Both low and high rates of Plinazolin significantly slowed the return of nymphs compared to the untreated control, and provided the same level of control as Warrior, statistically. Both rates also significantly reduced rates of hopperburn. The active ingredient in Plinazolin, isocycloseram, is classified as IRAC Group 30, which is a relatively new IRAC group with few active ingredients. Having additional modes of action to rotate between for pest control decreases the chances of pest resistance development and helps ensure the effectiveness of materials. Click on figure to enlarge.

Tarping for Vegetable Crops

What is tarping?

Tarping is a technique where opaque plastic sheets1 are used in order to kill weeds or cover crops2,3. Tarps are different from plastic mulch in that tarps are thicker, usually between 5-6 mils (0.005-0.006 inches), and can be reused for many years, generally around six1,2. Tarps are used for bed preparation and are removed before a crop is planted, as opposed to plastic mulch, which stays on the bed throughout the cropping season. Tarps are usually made from polyethylene, and are approved for use in organic production. Old billboard plastics have sometimes been recycled as tarps, but they are made from PVC, which is not allowed in organic production4. Silage tarps are easy to find and purchase, and so they are the most commonly used tarp material2. Typically, silage tarps are used white-side-out for silage storage, but they are more effective black-side-up when used to tarp vegetable beds. Sometimes, woven landscape fabric is used. This material repels water but is more permeable than other tarping materials.

Benefits of tarping

The primary benefit of tarping is killing weeds or terminating a cover crop. Plants are killed by blocking all sunlight, which is called occultation2. In addition to weed control, tarping can have added bed preparation benefits.

- Soil warming. If there is good tarp-soil contact and the tarp is dark-colored, the soil beneath will warm up faster than untarped soil in the spring.

- Regulate soil moisture. Tarps can also help regulate soil water content2. They are impermeable and can keep rainfall off beds, which helps during a wet spring. But they also prevent evaporation, which preserves moisture for seedbeds1,3.

- Available soil nitrate. Tarps also increase nitrate availability when first removed, with greater nitrate accumulation when tarps are in place for longer1. The specific mechanism for increased nitrate availability is still unclear, but may be due to increased microbial mineralization in warmer soils with consistent moisture, less leaching from rainfall, less nitrate uptake from germinating plants, or some combination of these factors2,5.

- Small-scale production. You do not need a tractor to use a tarp, so there is a low barrier to adoption2. It is also easy to apply tarps with 1-2 people, so they can be used on small scale farms with minimal labor availability2.

- Organic reduced tillage. Tarping is a weed management tool that does not require tillage or herbicides, so it could be a critical component of a farm looking to produce reduced- or no-till organic vegetables3,5.

How to tarp

Tarping has been under-researched and most experimentation has come from innovative small farms2. There are probably many ways to use a tarp that have not yet been optimized. Do not be afraid to try out a new use of a tarp, keeping these basic tarping steps in mind:

- Have an appropriately sized tarp.

- Tarps are usually 25 lbs per 1,000 ft2. Generally, one person can comfortably handle a 2,000 ft2 tarp (50 lbs), so it is recommended to use sections this size or smaller2.

- Tarps can be cut to fit one bed or multiple beds. Think about the tarping rotation you want to use on your own farm and size appropriately.

- Make sure tarps are slightly larger than your desired tarping area so that there is some overhang to weigh down the tarp and to accommodate raised beds4.

- Lay the tarp over the desired tarping area and secure.

- Place tarps black-side-up for the most soil warming benefit.

- Usually sandbags are used to secure the tarp, but growers have also used cement cinderblocks, old tires, or staples. Staples are most useful if using woven landscape fabric because otherwise they will create permanent holes that will speed up the degradation of the tarp4.

- Use more weight if keeping the tarp in place longer or if strong winds are expected.

- Leave the tarp on the soil surface for at least 3 weeks and until you are ready to plant1,2.

- The weed-free period after removing the tarp is about 3 weeks3. To gain the most benefit from tarping, do not remove it until you are ready to plant.

- To kill all plants, it is generally advised to leave the tarp in place for 3 weeks, but some farmers have found that weeds are killed faster during hot weather4.

- For perennial weeds, tarps may need to be in place for much longer than 3 weeks. More research in this area is needed, but some perennials may need to be tarped for several months, a year, or more to be killed2.

- Some farmers advise against tarping over the winter due to the potential for rodents to damage the tarp. However, removing the tarp over the winter may negate some of the soil moisture regulation benefits. Think about your goals and what is most beneficial for your own farm.

- Remove and properly store the tarp when ready to plant.

- Improper storage can lead to rodent damage and shorten the life of your tarp.

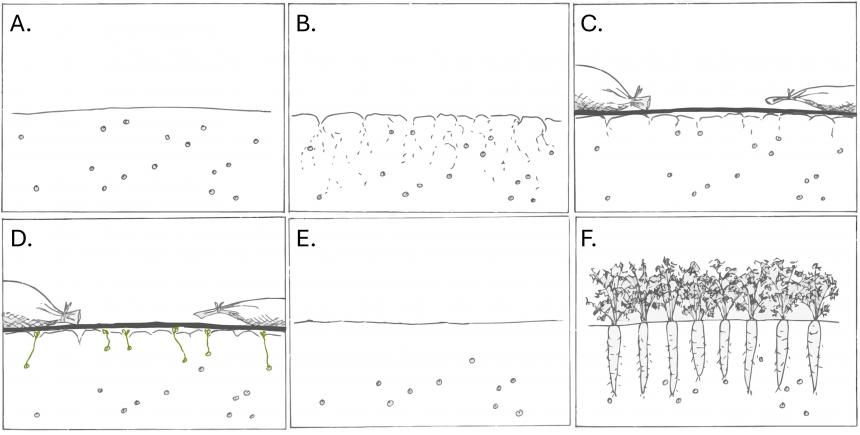

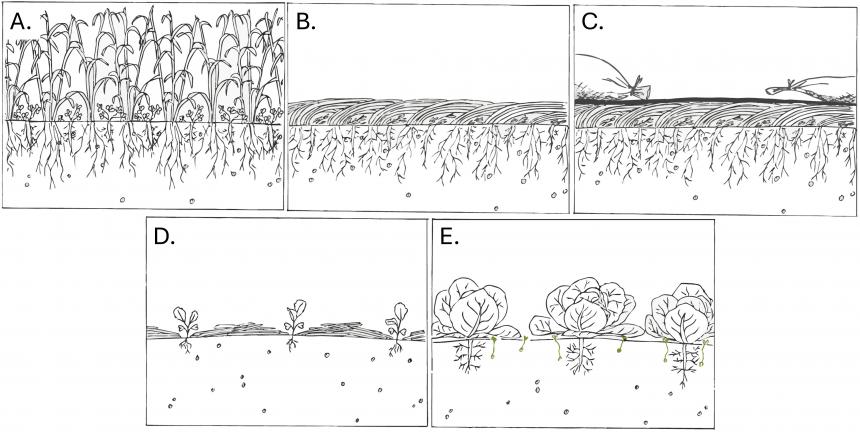

Tarping has been used most often in conjunction with a stale seedbed or with no-till cover cropping. When used with a stale seedbed, first till and prepare a bed2 [Fig. 1]. Tillage in this situation is important to stimulate the germination of weed seeds2. Tillage stimulates seed germination by exposing seeds to light, providing more oxygen, and warming the soil6. You want weed seeds to germinate so you can kill them with occultation and remove them from the soil seedbank. After preparing the bed, apply the tarp to kill any weeds that germinate. The planting beds should be 95-100% weed-free when you remove the tarp1,2,7. Be sure to reduce all soil disturbance after removal so that no new weed seeds are stimulated to germinate. The weed-free planting bed will give your crop time to establish without weed competition. This is a critical period to control weeds because once your crop is established, it will be much less susceptible to weed competition8. If you have time, and want to further reduce the soil seedbank, you can remove the tarp and till or irrigate a second time to further stimulate more weed seed germination. Kill these newly emerged weeds with additional tarping, flaming, or herbicides2. Research so far has not found a significant decrease in the weed seedbank after tarping, but more work in this area is needed1.

Cover crops bring a variety of benefits to a farm, but they can be difficult to terminate in an organic, no-till situation. Tarps can be very useful because of their ability to terminate a cover crop without tillage or herbicides [Fig. 2]. Before applying a tarp, often the cover crop is mowed or compressed. Mowing will distribute the cover crop unevenly across the field4, which makes the residue less useful as a mulch after removing the tarp. Compressing the cover crop creates a more even mulch layer but requires specialized equipment. Compression can be done with a roller-crimper or with small-scale equipment such as a lawn roller3. Put the tarp directly over the compressed cover crop to terminate it. This method will not warm the soil in the spring because the cover crop acts as an insulative barrier between the tarp and the soil3. Once you are ready to plant, you can remove the tarp. Large-seeded and transplanted crops can be directly planted into the cover crop residue. In this case, the cover crop residue will act as a mulch during the growing season and will suppress some weeds. The greater the cover crop biomass, the better the weed suppression. If you are planting small-seeded crops, you may need to rake off the cover crop biomass from the bed before planting. In this case, there will be little residual weed control from the cover crop.

Realistic expectations

Tarping is a powerful tool that can be incorporated into a wide variety of farms. It can be used in small, diversified farming systems that are both no- or low-till and organic. It has primarily been developed by farmers2, with much information being provided farmer-to-farmer rather than promoted by universities. A few formal research trials have been conducted, but there is still a lot of room to learn more about the effects of tarping. For a comprehensive summary of the current understanding of tarps, incorporating both grower case studies and university research, see the University of Maine Cooperative Extension Bulletin #1075 Tarping in the Northeast: A Guide for Small Famers.

Do not expect tarping to be a silver bullet. Even with complete weed control at planting, tarping will only provide control for several weeks. Often, it is used in the fall or early spring and adequately controls winter annuals and biennials. However, summer annuals will germinate as the soil continues to warm and thus, some additional weed control will be needed. If tarping is done later in the growing season, summer annuals may be better controlled, but winter annuals will begin to germinate later in the crop cycle. Have a plan to control these weeds. If using a tarp to terminate cover crops, cover crop biomass can reduce the need for tillage or cultivation for weed control later in the season, but escapes may happen, and they will need to be controlled by hand. The thicker the cover crop mulch, the fewer weed escapes will grow. If raking the cover crop residue from the beds before planting, more weed management will be needed during crop growth. If you have many perennial weeds, especially spreading perennials, tarping will be less effective at killing these weeds and the tarping duration will need to be much longer. Be sure to have a plan and temper expectations to not be discouraged. Tarping brings many potential benefits to a farm, such as an organic, no-till weed control option, labor savings, opportunities to better manage workload timing, and techniques for no-till bed preparation, leading to reduced erosion potential and increased soil health. But it also won’t eliminate weeds completely and that’s ok.

References

- Rylander, H. et al. Black Plastic Tarps Advance Organic Reduced Tillage I: Impact on Soils, Weed Seed Survival, and Crop Residue. HortScience 55, 819–825 (2020).

- Kubalek, R., Granatstein, D., Collins, D. & Miles, C. Review of Tarping and a Case Study on Small-scale Organic Farms. HortTechnology 32, 119–128 (2022).

- Lounsbury, N. P., Warren, N. D., Wolfe, S. D. & Smith, R. G. Investigating tarps to facilitate organic no-till cabbage production with high-residue cover crops. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 35, 227–233 (2020).

- Bulletin #1075, Tarping in the Northeast: A Guide for Small Farms - Cooperative Extension Publications - University of Maine Cooperative Extension. Cooperative Extension Publications https://extension.umaine.edu/publications/1075e/.

- Rylander, H. et al. Black Plastic Tarps Advance Organic Reduced Tillage II: Impact on Weeds and Beet Yield. HortScience 55, 826–831 (2020).

- Chancellor, R. J. Tillage Effects of Annual Weed Germination. in World Soybean Research Conference III (CRC Press, 1986).

- Birthisel, S. K. & Gallandt, E. R. Trials Evaluating Solarization and Tarping for Improved Stale Seedbed Preparation in the Northeast USA. Org. Farming 5, 52–65 (2019).

- Knezevic, S. Z., Evans, S. P., Blankenship, E. E., Acker, R. C. V. & Lindquist, J. L. Critical period for weed control: the concept and data analysis. Weed Sci. 50, 773–786 (2002)

--Written by Maria Gannett, UMass Extension Weeds Specialist

Cleaning & Disinfecting the Greenhouse

If you’ve had recurring problems with diseases such as damping off or insects such as fungus gnats or aphids, perhaps your greenhouse and potting areas need a good cleaning. Vegetable growers are now mostly done using their greenhouses for transplant production, and if they are not being used to store fall crops, now is a good time to clean the houses well before next season’s big rush. Some growers wait until the week before opening a greenhouse to clean debris from the previous growing season, but cleaning up as early as possible helps eliminate overwintering sites for pests and reduces their populations prior to the spring growing season. Pests outbreaks are much easier to prevent than cure.

Cleaning

Cleaning involves physically removing weeds, debris, and soil, and is the first step prior to disinfecting greenhouse surfaces and equipment. Soil and organic residues from plants and growing media reduce the effectiveness of disinfectants. There are some cleaners specifically developed for greenhouse use, including Strip-It, which is a combination of sulfuric acid and wetting agents formulated to remove algae, dirt, and hard water deposits. Some growers use a wet/dry vacuum on concrete and covered floors to remove debris. High-pressure power washing with soap and water is also an option. Soap is especially useful in removing greasy deposits. Soap residues must be rinsed thoroughly as they can cause certain disinfectants such as Q-salts to become inactive.

- Begin at the top and work your way down. Sweep down walls and internal structures and clean the floor of soil, organic matter, and weeds. Disease-causing organisms can be lodged on rafters, window ledges, tops of overhead piping, and folds in plastic. Extra care is needed to clean these areas as well as textured surfaces such as concrete and wood, which can harbor many kinds of pests.

- Install physical weed mat barriers if floors are bare dirt or gravel and repair existing mats to prevent weeds from germinating and make it easier to manage algae. Avoid using gravel on top of the weed mat, as it will trap soil and moisture, creating an ideal environment for weeds, diseases, insects, and algae.

- Clean irrigation filters to remove dirt and microbial buildup (or biofilm) at the end of the growing season. Growers often use products labeled for cleaning irrigation systems such as sulfuric acid plus a wetting agent (e.g. Strip-It) or sanitizers containing hydrogen peroxide and peroxyacetic acid (e.g. SaniDate) to flush out slime and debris.

Disinfecting

Many pathogens can be managed to some degree using disinfectants. For example, dust particles from fallen growing medium or pots can contain bacteria or fungi such as Rhizoctonia or Pythium. Disinfectants will help control these pathogens. In addition to plant pathogens, some disinfectants are also labeled for managing algae, which is a breeding ground for fungus gnats and shore flies.

Greenhouse Benches and Work Tables

If possible, use benches made of wire or other non-porous materials, such as a laminate, that can be easily disinfected. Wood benches can be a source for root rot diseases and insect infestations. Algae tend to grow on the surface of the wood, creating an ideal environment for fungus gnats and shore flies, and plant pathogens can grow within the wood. Plants rooting through containers into the wood will develop root rot if conditions are favorable for pathogen activity. Disinfect benches between crop cycles with one of the labeled products listed below. Keep in mind that disinfectants are not protectants—they may destroy certain pathogens but will have little residual activity.

If possible, use benches made of wire or other non-porous materials, such as a laminate, that can be easily disinfected. Wood benches can be a source for root rot diseases and insect infestations. Algae tend to grow on the surface of the wood, creating an ideal environment for fungus gnats and shore flies, and plant pathogens can grow within the wood. Plants rooting through containers into the wood will develop root rot if conditions are favorable for pathogen activity. Disinfect benches between crop cycles with one of the labeled products listed below. Keep in mind that disinfectants are not protectants—they may destroy certain pathogens but will have little residual activity.

Cleaning Containers

Plant pathogens such as Pythium, Rhizoctonia, and Thielaviopsis can survive in root debris or soil particles on greenhouse surfaces. If a crop had a disease problem, then avoid re-using containers. Containers to be re-used should be washed thoroughly to remove soil particles and plant debris before being treated with a disinfectant, even if there is no evidence of disease in the crop. Debris and organic matter can protect pathogens from contacting the disinfectant solution and can also reduce efficacy of certain disinfectants.

Disinfectants for Greenhouses

If possible, disinfectants should be used on a routine basis both as part of a pre-crop clean-up program and during the cropping cycle. There are several different types of disinfectants that are currently used in the greenhouse for plant pathogen and algae control listed below. Remember that sanitizers and disinfectants are pesticides and may have serious health consequences if not used according to their labels. Be sure to use an appropriate product for the pathogen and for the surface material you are trying to disinfect and use good ventilation and proper personal protective equipment.

Quaternary ammonium chloride salts (Green-Shield II, Physan 20, KleenGrow)

Q-salt products, commonly used by growers, are quite stable and work well when used according to label instructions. Q-salts are labeled for fungal, bacterial, and viral plant pathogens, as well as algae. They can be applied to floors, walls, benches, tools, pots, and flats as disinfectants. Physan 20 is also labeled for use on seeds, cut flowers, and plants. Carefully read and follow label instructions. Use directions may vary according to the intended use of the product. For example, the Green-Shield II label states that objects to be disinfected should remain wet with the product for 10 minutes, and walkways for an hour or more. Instructions allow for surfaces to be wiped or air-dried after treatment. For cutting tools that are being dipped between uses, one way to allow them to remain wet for the appropriate amount of time is by having two cutting tools, one pair to use while the other is soaking.

Q-salts are not protectants. They will kill the pathogens for which they are labeled on contact but will have little residual activity. Presence of organic matter will inactivate them, so pre-clean objects to dislodge organic matter prior to application. KleenGrow does have a higher organic matter tolerance and longer residual activity on hard surfaces. Because it is difficult to tell when the product becomes inactive, prepare fresh solutions frequently (twice a day if in constant use). The products tend to foam a bit when they are active; when foaming stops, it is a sign they are no longer effective. No rinsing with water is needed.

Peroxyacetic acid (PAA) (ZeroTol 2.0, OxiDate 2.0, SaniDate 12.0)

PAA kills bacteria, fungi, algae, and their spores immediately on contact. It is labeled as a disinfectant for use on greenhouse surfaces, equipment, benches, pots, trays, and tools, and for use on plants. Label recommendations state that all surfaces should be wetted thoroughly before treatment. Several precautions are noted. PAA has strong oxidizing action and should not be mixed with any other pesticides or fertilizers. When applied directly to plants, phytotoxicity may occur for some crops, especially if applied above labeled rates or if plants are under stress. PAA can be applied through an irrigation system. As a concentrate, it is corrosive and causes eye and skin damage or irritation. Carefully read and follow label precautions. Note that OxiDate and SaniDate are OMRI-listed for organic production.

Sodium carbonate peroxyhydrate (GreenClean Pro Granular Algaecide)

This disinfectant is granular and activated with water. Upon activation, sodium carbonate peroxyhydrate breaks down into sodium carbonate and hydrogen peroxide. Green¬Clean is labeled for managing algae in any non-food water or surfaces. Non-target plants suffer contact burn if undiluted granules are accidentally spilled on them.

Chlorine bleach

There are more stable products than bleach to use for disinfecting greenhouse surfaces, but when used properly, it is an effective disinfectant. Chlorine bleach may be used for pots or flats, but is not recommended for application to walls, benches, or flooring. A solution of chlorine bleach and water is short-lived and the half-life (time required for a 50% reduction in strength) of a chlorine solution is only two hours. After two hours, only ½ as much chlorine is present as was present initially. After four hours, only ¼ is there, and so on. To ensure the effectiveness of chlorine solutions, it should be prepared fresh just before each use. The concentration normally used is one part of household bleach (5.25% sodium hypochlorite) to nine parts of water, giving a final strength of 0.5%. Some bleach products are more concentrated—check the percent active ingredient for the product you are using and see the label for the recommended dilution rate. Chlorine is corrosive. Repeated use of chlorine solutions may be harmful to plastics or metals. Soak objects to be sanitized for 30 minutes and then rinse with water. It should also be noted that bleach is phytotoxic to some plants, such as poinsettias. Chlorine can also irritate the respiratory system and so should only be used in well-ventilated areas.

Alcohol

Alcohol (70%) is a very effective sanitizer that acts almost immediately upon contact. It is not practical as a soaking material because of its flammability. However, it can be used as a dip or swipe treatment on knives or cutting tools. No rinsing with water is needed. Alcohol, although not used as a general disinfectant, is mentioned here because it is used by growers to disinfect propagation tools.

OMRI-listed organic disinfectants include OxiDate 2.0, SaniDate 12.0, ZeroTol and others. Ethyl or isopropyl alcohol is used to disinfect tools. Organic growers should always check with their certifying organization before using any material new in their growing practices. For a list of products, visit the OMRI website.

This information is supplied with the understanding that no discrimination is intended and no endorsement of any particular product is implied. If any information in this article is inconsistent with the label, follow the label.

Managing Algae

Algae are a diverse grouping of organisms that occur in a wide range of environments. Algae growth on walkways, water pipes, equipment, greenhouse coverings, on or under benches, and in pots is an ongoing problem for growers. Algae form an impermeable layer on the media surface that prevents wetting of the media below and can clog irrigation misting lines and emitters. Algae are also a food source for insect pests like shore flies and cause slippery walkways that can be a liability risk for workers and customers. Recent studies have shown that algae are brought into the greenhouse through water supplies and from peat in growing media. In a warm, moist environment with fertilizer, the algae flourish.

Proper water management and fertilizing can help to slow algal growth. Avoid over-watering slow-growing plants, especially early in the production cycle. Allow the surface of the media to dry out between watering. Avoid excessive fertilizer runoff and puddling water on floors, benches, and greenhouse surfaces. The greenhouse floor should be level and drain properly to prevent the pooling of water prior to installing a physical weed mat barrier. Algae management involves an integrated approach involving sanitation, environmental modification, and frequent use of disinfectants.

--Prepared by Tina Smith, UMass Extension Educator, Greenhouse Crops and Floriculture Program (retired). Updated for 2020 by L. McKeag. For references and resources, see the online version of this article for the UMass Extension Greenhouse Crops and Floriculture Program here.

News

Notice on Current Drought Declaration Across Massachusetts

On November 19, Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA) Secretary Rebecca Tepper elevated the Western, Connecticut River Valley, and Southeast regions to be at a Level 3 – Critical Drought. The Central and Northeast regions continue to be at a Level 3 – Critical Drought due to the lower-than-average precipitation over the past three months. The lack of rainfall has allowed for an unprecedented increase in brush fires in Massachusetts with many occurring in populated areas.

On November 19, Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA) Secretary Rebecca Tepper elevated the Western, Connecticut River Valley, and Southeast regions to be at a Level 3 – Critical Drought. The Central and Northeast regions continue to be at a Level 3 – Critical Drought due to the lower-than-average precipitation over the past three months. The lack of rainfall has allowed for an unprecedented increase in brush fires in Massachusetts with many occurring in populated areas.

In order to mitigate the risks associated with these dry conditions, MDAR is asking the Massachusetts agricultural community to remain vigilant and refrain from engaging in any burn operations on agricultural production acreage. Additionally, MDAR is asking that livestock operations conserve water usage when possible, in light of the current drought declaration.

For more information on the drought conditions in Massachusetts, visit EEA’s drought management page at https://www.mass.gov/guides/drought-management-in-massachusetts.

Organic Certification Cost Share Program

Reminder to certified organic growers, the 2024 Organic Cost Share Reimbursement application period is open and deadline to submit applications is December 16, 2024.

MDAR is authorized by the USDA – Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) to reimburse certified Organic Crop and Livestock Producers and Handlers (processors) for the Federal 2024 Fiscal Year. Reimbursements are limited to 75% (seventy-five percent) of an operation’s certification costs, up to a maximum of $750 (seven hundred fifty dollars) of certification, for the program year. Organic operations certified for crops, wild crops, livestock and handlers are eligible to participate.

If you would like to be listed on the MassGrown Map as an Organic Farm, please fill out MDAR’s Map Form. For those already on the Map, and have updates or edits for your farm, please send them to Richard.LeBlanc@mass.gov.

New Northeast SARE Historically Underserved Farming Communities Grant Program

Applications due: Tuesday, January 7, by 5pm

The historically underserved farmer/farming communities grant program is designed to address systemic/structural barriers to access that disproportionately limit the ability of historically underserved farmer/farming communities to fully participate in SARE programs.

This grant program funds projects that create farming and food system opportunities for historically underserved farmers/farming communities and prioritizes work that engages, and is led by, people with experience from those communities. The program seeks projects that will address the needs and serve the interests of groups that have been met with discrimination and other systemic obstacles to full participation in the agricultural system of the Northeast.

Northeast SARE understands Historically Underserved Farmers to align with the USDA definition of socially disadvantaged farmers and ranchers as those belonging to groups that have been subject to racial or ethnic prejudice, including but not limited to farmers who are Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Hispanic or Latino, and Asian or Pacific Islander.

Awards can range from $150,000 to $250,000 depending upon a project’s needs, complexity, and duration. Approximately 15-20 awards will be made.

A wide variety of topics can be funded by this grant program, including but not limited to:

- The study and/or promotion of culturally appropriate best management practices

- Production of specialty, ethnic, and medicinal crops

- Climate-smart agricultural practices

- Urban and indigenous agriculture systems

- Equitable access to markets for agricultural products

- Equitable acquisition of farming and marketing infrastructure

- Budgeting, financial planning, accounting, tax, and insurance management education

- Capacity and relationship building related to sustainable agriculture

- Professional development for producers and/or people that work with them

- Programs supporting mental and physical health for producers

- Improving local and regional food access for underserved communities

- Historically Underserved farming community urban and rural partnerships

- Policy development and community capacity building

Informational Sessions: December 4 & 10, 2-3pm. Click here to register.

Questions? Contact ne-huf@sare.org.

MDAR Climate Smart Agriculture Program Round II – Applications due January 7

Program website: https://www.mass.gov/how-to/how-to-apply-to-the-climate-smart-agriculture-program

Applications due: Tuesday, January 7, 2025, 4pm

MDAR is now accepting applications from agricultural operations who wish to participate in the Climate Smart for Agriculture Program (CSAP).

The CSAP grant seeks to support farmers in adapting to changing climate conditions through practices that improve soil health, ensure the efficient use of water, prevent impacts on water quality, reduce energy use and reduce the use of fossil fuels, while also encouraging the use of innovative technologies that improve resource efficiency. It aims to strengthen local food systems, improve farm productivity, and ensure long-term sustainability, all while reducing the environmental footprint of agriculture.

CSAP is a competitive, reimbursement grant program that funds projects 80% of total project costs up to a maximum of $50,000. This round of funding is for projects that can be completed in a short timeframe and are able to be completed by June 30, 2025.

NOTE: Applicants who submitted proposals under the first round of CSAP are eligible to apply but cannot submit an application for the same project.

Please refer to program website to download a copy of the Request for Response (RFR), which contains eligibility information, project examples, and the questions that are included in the online application. Applications must be submitted through the online application to be considered.

Questions? Contact Laura Maul at Laura.Maul@mass.gov or (857) 507-5972

Events

New England Vegetable & Fruit Conference - Early bird registration through November 30

When: Tuesday - Thursday, December 17-19, 2024, 8am-6pm daily

Where: Doubletree Hotel, 700 Elm St., Manchester, NH 03101

Registration: Before November 30, $115/person, or $85 for additional attendees if registering as a group. Students $50. Registration capped at 1,400. Click here to register.

The NEVF Conference includes more than 25 educational sessions over three days, covering major vegetable, berry and tree fruit crops as well as various special topics. A Farmer-to-Farmer meeting after each morning and afternoon session will bring speakers and farmers together for informal, in-depth discussions on certain issues. The extensive trade show has over 120 exhibitors.

Mount Grace Agricultural Resource Fair

When: Wednesday, December 4, 1-5pm

Where: Red Apple Farm, 455 Highland Ave., Phillipston, MA 01331

Registration: Free, and registration not required. But, pre-register to receive a free soil test voucher from the UMass Soil & Plant Nutrient Testing Lab! Click here to register.

Mount Grace is hosting an agricultural resource fair aimed at connecting the Massachusetts agricultural community with resources provided by non-profit agricultural stakeholders and government partners. This free event will start with a soil health workshop led by UMass Extension. Stick around after the workshop to learn more about resources offered through the following service providers:

- American Farmland Trust

- MDAR

- NRCS

- Northeast Organic Farming Association (NOFA)

- Worcester County Conservation District

- USDA Farm Service Agency

Light refreshments will be provided. Pre-register for the event to receive a free soil test voucher through the UMass Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Lab. Learn more about the soil test here: https://ag.umass.edu/services/soil-plant-nutrient-testing-laboratory/ordering-information-forms

Questions? Contact Jessie Fagan, fagan@mountgrace.org.

2025 Get Ready for Spring Greenhouse Education Program, Part 1

When: Tuesday, January 14, 2024, 8:30am-12pm

Where: Online

Registration: $25/person. Click here to register.

Topics:

- A New Option for Controlling Plant Growth with Ethephon Drenches

- Identification and Management Strategies for Bacterial and Fungal Leaf Spots on Spring Greenhouse Crops

- How to Optimize Biocontrol Programs to Ensure Successful Pest Management Outcomes

3 pesticide recertification credits for MA categories 26, 29, 31, and 000 (Applicator’s/Core License) are available for this program.

Gracious support from the Massachusetts Flower Growers Association has reduced participation fees for these events as a benefit to the industry.

Questions? Contact Geoffrey Njue, gnjue@umass.edu, 617-243-1932.

MDAR’s Agricultural Business Training Program

This program offers several courses for Massachusetts agricultural enterprises on business planning and farm transfer. Click the links for more information on each course:

When: Dates TBD based on interest. Expected to begin in January 2025.

Where: Location TBD based on interest. Hybrid, with both in-person and virtual classes.

Registration: Click here to fill out an application. $150 per farm for up to two owner/operators. It is important to us that the course fee does not create a barrier to participation. If the fee would prevent you from participating, please contact Melissa to discuss waiving the fee.

A hands-on course to help established farmers develop a farm business plan with financial projections. This course has been approved as a certified USDA Farm Service Agency (FSA) borrower training for financial management. Submit an application to get on the registration list!

Questions? Contact Melissa Adams, Melissa.L.Adams@mass.gov, 857-276-2377.

When: Starting March 2025

Registration: Free. Rolling applications accepted. Apply by January 15 to begin work this spring. See program page for application information, HERE.

This program is for Massachusetts farm owners who have already identified a successor interested in transitioning ownership and management of the farm. Work one-on-one with an experienced planner over the course of a year to set retirement goals and create tangible next steps for the transfer of management and assets. Note that these advisors have experience working with farm operations on business management, financials, and farm transfer. They will not provide legal or tax advice but will help you develop an action plan that identifies concrete next steps to work on with your attorney and/or CPA to make the transfer happen.

An informational webinar will be held on Wednesday, December 11 at 12pm – register here.

Questions? Contact Laura Barley at 857-507-5548 or Laura.Barley@mass.gov.

- Land for Good’s Succession School - seeking participants for winter session in Taunton - Fill out the Interest Form today!

When: Mondays, January 27, February 24, and March 17, 9:30am - 3:30pm

Where: Taunton Public Library (location dependent on sufficient interest)

Registration: $100 per farm. Click here to fill out an interest form.

This is an opportunity for senior generation farmers. with or without identified successors, to talk with peers, learn from advisors, and get support on the challenging process of farm succession and transfer planning. Succession School provides farmers and farming partners with the structured and sustained support to make decisions, engage their families, and organize the legal and financial mechanics of farm succession.

Questions? Contact Deanna at 339-235-0859 or deanna@landforgood.org.

2025 Mass Aggie Seminar Series

When: Saturdays, February 15 & 22, and March 1, 22 & 29, 10am – 12pm

When: Saturdays, February 15 & 22, and March 1, 22 & 29, 10am – 12pm

Where: Zoom

Registration: $45 for each session. Online registration will close the Friday prior to each seminar. Click here to register, or see the series website, HERE, for information on registering via mail.

The Mass Aggie seminar series is a program for small-scale backyard fruit growers and agricultural enthusiasts of all types that highlights the agricultural expertise and innovation available through the University of Massachusetts Amherst’s Extension Fruit Team. The series provides a platform for small scale backyard growers and agricultural enthusiasts of all types to come together to learn the latest developments in fruit production. Delve into the cutting-edge information shared in our seminars, curated to empower individuals with the tools and knowledge needed to navigate the ever-evolving landscape of agriculture.

- February 15: Insects – Pests and Beneficials – Jaime Piñero

- February 22: Ecological Weed Management in the Home Orchard – Maria Gannett

- March 1: Orchard Sustainability Through IPM – Liz Garofalo

- March 22: Orchard Pruning – Jon Clements

- March 29: Home Orchard Establishment – Jon Clements

See the series website, HERE, for details about each session.

Vegetable Notes. Maria Gannett, Genevieve Higgins, Lisa McKeag, Susan Scheufele, Alireza Shokoohi, Hannah Whitehead, co-editors. All photos in this publication are credited to the UMass Extension Vegetable Program unless otherwise noted.

Where trade names or commercial products are used, no company or product endorsement is implied or intended. Always read the label before using any pesticide. The label is the legal document for product use. Disregard any information in this newsletter if it is in conflict with the label.

The University of Massachusetts Extension is an equal opportunity provider and employer, United States Department of Agriculture cooperating. Contact your local Extension office for information on disability accommodations. Contact the State Center Directors Office if you have concerns related to discrimination, 413-545-4800.