Elm Anthracnose

Elm anthracnose, sometimes known as black spot of elm, is caused by the fungal pathogen Gnomonia ulmea (formerly Stegophora ulmea)

Hosts

In southern New England, elm anthracnose is most common on American elm (Ulmus americana), Scotch elm (U. glabra) and European white elm (U. laevis), but can also be found on slippery elm (U. rubra), rock elm (U. thomasii) and Japanese zelkova (Zelkova serrata).

Symptoms & Signs

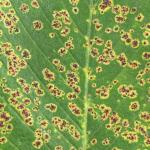

Gnomonia ulmea is a native pathogen in North America and is widespread in the northeast. The fungus overwinters in the buds and also survives within discarded leaves. In the spring, when temperatures reach at least 45° F for several days, spores are discharged from fruiting bodies and are spread by wind and rain to establish new infections. Spores germinate under moist conditions, penetrate the newly developing leaf or stem tissue and produce the characteristic black spots within 10–20 days of infection. Initial symptoms appear as small, circular, yellow-colored leaf spots that form as leaves unfold from the buds. Over time, the spots darken and become raised on the surface. When numerous developing spots are present, they can coalesce to form large, irregularly-shaped, foliar blotches that are surrounded by a white border of necrotic tissue. Symptoms can also develop on petioles and succulent stems, resulting in shoot blight. Symptoms tend to appear first in the lower canopy, as spores discharged from nearby leaf litter provide a large source of primary inoculum. When severe, the disease can cause premature defoliation early in the growing season. Like most anthracnose fungi, the pathogen goes dormant during warmer and drier conditions in mid-summer. The disease is usually not a primary stress for elms in the landscape. More often, individual branches in the canopy are symptomatic, and the damage can appear similar to flagging from Dutch elm disease. Secondary infection through the repeated production of asexual spores continues throughout the summer, as long as conditions remain cool and wet. Elm anthracnose can cause serious defoliation of susceptible trees in wet years and is especially severe in areas where cool, moist weather is common in the spring and early-summer.

Management

In areas where elm anthracnose is a chronic problem (e.g. locations with cool weather and fog early in the growing season) pruning to promote air movement and sunlight on the lower canopy can reduce disease incidence. Air circulation should be considered when planting trees in settings where elm anthracnose is a problem. Elm species vary in their susceptibility to disease, with American elm (U. americana), Scotch elm (U. glabra) and European white elm (U. laevis) considered as the most susceptible to infection. In areas of high disease pressure, elm species with better resistance to the pathogen should be chosen for planting. When the disease is confirmed, remove discarded leaves on the ground and prune any branches that may have died over the season to reduce inoculum. If left at the site, the fungus will be in close proximity to establish new infections the following year. Preventative fungicide treatments can be utilized in the spring as new leaves are developing to prevent infection. However, fungicides are often not necessary unless disease pressure is high and trees are suffering from chronic infections.