Rhizosphaera Needle Cast

Pathogen

Rhizosphaera needle cast is caused by several species in genus Rhizosphaera, and while the ecology and pathogenicity of these species are poorly understood, the disease is most often attributed to R. kalkhoffii. Research from the UMass Plant Diagnostic Laboratory (unpublished) has identified seven phylogenetic species in the northeast from six host genera (Picea, Abies, Tsuga, Pinus, Pseudotsuga and Cedrus). Based on this dataset, R. kalkhoffii infects spruce with few exceptions.

Hosts

Colorado blue spruce (Picea pungens), white spruce (P. glauca) and Oriental spruce (P. orientalis) are the most severely affected, while Norway spruce (P. abies) and red spruce (P. rubens) are more resistant to the disease. However, when stressed by drought, many spruce species become susceptible. True fir (Abies), especially white fir (A. concolor), can suffer severe damage as well. Additional hosts in New England include pine (Pinus), hemlock (Tsuga), Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga), and true cedar (Cedrus) but these infections rarely result in serious injury.

Symptoms & Signs

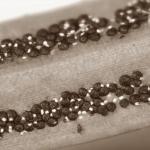

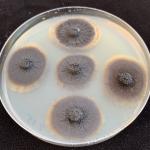

Mild temperatures and prolonged needle wetness favor disease development. The pathogen invades susceptible needles through the stomata (pores used for gas exchange) and overwinters in diseased needles that remain in the canopy or have fallen beneath the tree. Beginning in the spring and lasting through the autumn season, spores are dispersed from infected needles by wind and splashing rainwater. The spores can persist on dry needles for several weeks until environmental conditions become favorable for germination and invasion. Needles on interior branches in the lower canopy are most commonly infected first. In these locations, air flow is limited, shade is more abundant and free moisture persists on needles longer. Once the needles are infected, symptoms may take 12 months or longer to become visible. When trees are stressed, symptoms of infection may develop the same season. On blue and white spruce, diseased needles often first appear purple, becoming brown to straw-colored over time. When the disease becomes well established in the lower canopy of a tree, Rhizosphaera then spreads upward in successive years, gradually leading to increased rates of premature needle shedding. In certain settings, mature trees can experience serious needle loss, leaving only a small tuft of live foliage in the upper canopy. Pycnidia (small, black-colored fruiting bodies of the fungus through which spores are discharged) develop on the surface of infected needles and can be observed with the naked eye or a 10X hand lens during almost any season. They appear as a sooty dust on the needles.

Management

Spruce vary in their susceptibility to the disease, so if disease pressure in the landscape is high, choose resistant species such as Norway spruce for new plantings. The disease is more destructive on spruces planted in shaded settings or in tight hedgerows. Many spruces used as landscape ornamentals are shade intolerant and prefer full sun with no surrounding plants to thrive. Environmental stresses such as drought, deep planting and mechanical root injury contribute to disease severity. Additionally, opportunistic stem cankering fungi and insect pests also contribute to disease severity by reducing host vigor. When branches in the lower canopy decline or die, they should be pruned out to limit the establishment and spread of opportunistic pathogens. Fungicides may be effective in certain cases but will likely have little impact once the fungus is well established in the canopy. Chemicals labeled for use in the landscape against Rhizosphaera include: azoxystrobin, copper salts of fatty and/or rosin acids, copper hydroxide, copper hydroxide + mancozeb, mancozeb, metconazole, thiophanate-methyl and phosphites. Fungicides should be applied in the spring when new growth is 1/2 inch long and then again on regular intervals should wet weather persist. Autumn applications may also be necessary. It should be kept in mind that infections can take place anytime during the growing season when environmental conditions allow. In many cases, even with aggressive cultural and chemical control, trees will only maintain their current appearance. It may be more prudent to replace severely diseased blue spruce with new trees or shrubs.