Root and Butt Rot caused by Niveoporofomes spraguei

Pathogen

The native fungal pathogen Niveoporofomes spraguei, previously known as Fomitiopsis, Polyporus, Trametes and Tyromyces (Han et al. 2016), does not have a widely accepted common name.

Hosts

Niveoporofomes is a lesser-known but common root and butt rot pathogen of oaks (Quercus spp.) in the northeast (Luley 2022). While oak is the primary host, N. spraguei has been found on maple (Acer), birch (Betula), chestnut (Castanea), beech (Fagus), ash (Fraxinus), walnut (Juglans), cherry (Prunus), and elm (Ulmus) (Hepting 1971).

Symptoms & Signs

Infections by Niveoporofomes result in a brown cubical rot of the heartwood in the roots and lower trunk. The decay column can occasionally progress upwards in the trunk to significant heights. Because the decay is mostly restricted to the heartwood, infected trees often appear healthy and exhibit no symptoms of the disease. At times, excessive basal tapering (or flaring) may be the only external symptom present. The pattern of decay (brown rot) preferentially targets cellulose, resulting in major reductions in wood bending strength (Schwarze et al. 2000). This can seriously compromise the tree's structural stability when the decay is offset from the center or encompasses a large percentage of cross-sectional area in the roots and lower trunk. Infected trees may be susceptible to uprooting or stem breakage under loading from strong winds. Overall, N. spraguei is poorly studied and much remains unknown about the rate the decay and the incidence of advanced infections in urban trees. Like many other wood decay fungi, Niveoporofomes can persist as a saprophyte within infected stumps and roots.

Niveoporofomes produces fleshy (but durable) annual conks consisting of one to several overlapping caps that are typically produced directly from the infected trunk. However, they can also occur on lateral roots close to the flare. The cap may be white to gray with a reddish-brown margin when fresh. In some cases, the entire conk is reddish-brown. Young conks will often exude water droplets from both the upper and lower surfaces. In Massachusetts, fruiting bodies typically first appear from late July into August. Over time, the water droplets dry and colors fade, giving the conks a bleached gray appearance. The pore layer is off-white and typically becomes greenish when bruised and handled. The context is zonate and has a marbled appearance that persists even when the conks are older. The fruiting bodies may be highly distorted in appearance if the site is exposed and dry. The presence of conks is not a reliable indicator of infection as trees may harbor advanced infections with no conks.

Management

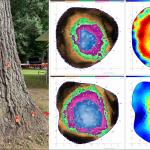

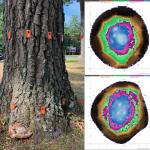

As with any tree infected by a root and butt rot pathogen, maintaining high tree vigor is important. If annual increment growth can keep pace with the rate of decay in the heartwood, this may reduce the risk of failure. Maintain a large ring of mulch or wood chips around the tree and manage insect pests and pathogens that can weaken the tree. Improving soil quality may also increase vigor. Pruning to reduce canopy sway can also be performed. Regularly scout oaks for the presence of fruiting bodies and document their occurrence on and around the lower trunk. Conks may appear annually for many years around the base of infected oaks. Minimally invasive decay detection techniques, such as resistance drilling and sonic tomography, are often required to understand the extent of the decay. Tomography scanning of infected trees in Massachusetts has revealed dramatic differences in decay severity when conks are present. In some cases, trees with only a single conk have significant lower trunk rot. While at other times, trees with multiple conks at the base have no detectable decay in the lower trunk. This serves as an important reminder that the presence of conks does not always indicate serious decay is present in the lower trunk.

References

Han ML, Chen YY, Shen LL, Song J, Vlasák J, Dai Y-C, and Cui B-K. 2016. Taxonomy and phylogeny of the brown-rot fungi: Fomitopsis and its related genera. Fungal Diversity 80: 343–373. doi.org/10.1007/s13225-016-0364-y

Hepting GH. 1971. Diseases of Forest and Shade Trees of the United States. Washington, DC: USDA Agricultural Handbook No. 386.

Luley, CJ. 2022. Niveoporofomes spraguei. In: Wood Decay Fungi Common to the Northeast & Central United States, 2nd Edition. Urban Forest Diagnostics LLC, Naples, NY. Pp. 72–73.

Schwarze FWMR, Engels J, and Mattheck C. 2000. Fungal Strategies of Wood Decay in Trees. Springer, Berlin, Germany.