Root and Butt Rot caused by Phaeolus schweinitzii

Pathogen

The fungal pathogen Phaeolus schweintizii (known as the velvet-top fungus) is responsible for brown cubical root and butt rot.

Hosts

Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) is the primary host in southern New England, but the disease is also common on two- and three-needle pines, spruce (Picea) and larch (Larix). Occasionally, the pathogen can be located on hemlock (Tsuga) and true fir (Abies) but these cases are uncommon.

Symptoms & Signs

Like many root and butt rot diseases, symptoms of infection can range from very general to non-existent. Overall, root and butt rot diseases symptoms of conifers can manifest as: canopy dieback/thinning, premature needle shedding, excessive basal tapering, resinosis from the lower trunk and a stress cone crop. Typically, brown cubical root and butt rot goes undetected until trees are large and suffer from stem breakage or uprooting. As the name implies, P. schweinitzii causes a brown rot, meaning the cellulose and hemicellulose are preferentially targeted while the lignin remains in a modified form. The decaying wood appears brown and separates into cubical sections. At advanced stages, the wood becomes very dry and powdery. Brown rot results in severe reductions in wood bending strength, making trees susceptible to stem breakage and uprooting under loading from strong winds. Decay columns can advance to significant heights within the main trunk. Annual fruiting bodies develop at the base of infected trees or from lateral roots nearby. They can appear from mid-August through September in southern New England but seem to be most abundant in mid- to late August. The presence of a single fruiting body does not automatically indicate serious decay is present. The mushrooms develop a short and thick stalk and the upper surface of the cap is yellow-brown and velvety to the touch when young. The underside is a similar color and has angular-shaped pores. After a short period of time, especially when exposed to near freezing temperatures, the mushrooms become dark reddish-brown and can blend into nearby surroundings. Once advanced decay has developed, fruiting bodies will often develop at the base of infected trees each year. However, at times mushrooms may not appear certain years after several years of production and cannot be relied upon solely to determine decay incidence. Spore dispersal is believed to be the primary means of overland spread. Once established in the soil, the fungus penetrates fine roots or may potentially invade roots infected by other fungi (e.g. Armillaria). Root to root contacts are not believed to be a primary means of disease spread in forest and landscape settings.

Management

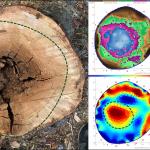

Active management for trees with root and butt rot infections is very difficult. Avoid planting conifers like eastern white pine in shallow and poorly-drained soils as these site conditions can predispose trees to infection. If multiple fruiting bodies are appearing annually, these trees should receive a thorough risk assessment and be closely monitored in the future. Advanced testing methods, such as tomography or resistance drilling, may be necessary to determine the extent of the damage. Canopy symptoms often fail to manifest since the pathogen typically occupies the center of the roots and heartwood in the lower trunk. Decay usually expands very slowly over time, radiating outward from the center of the trunk. Therefore, even with significant decay, infected trees may be structurally stable if the outer shell remains intact. When root decay is severe, a gradual thinning of the canopy and dieback from the top down may be visible. Badly diseased trees can be uprooted after loading from strong winds but more often failure occurs on the lower trunk.