Aztecs, Ambassador Poinsett, and Poinsettia

This article was written by Mark Hoddle, who was a graduate student at the time, studying biological control of whitefly on poinsettia. The reprinted article was originally published in Floral Notes newsletter, University of Massachusetts, Volume 6, No. 6 (May-June 1994)

Mark Hoddle

Department of Entomology University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA

The majority of people who read Floral Notes are aware that poinsettia is ubiquitous at Christmas. Where ever you go, this coquette plant is waiting to be admired: towering poinsettia Christmas trees decorate hotel lobbies; it festoons the balconies of shopping malls; arabesque arrangements adorn reception areas of restaurants; your own home may have this red and green spurge sitting on the living room table. There is no sanctuary or haven from poinsettia at Christmas. This is probably no surprise to poinsettia enthusiasts. Growers in Massachusetts manage to produce around 5 million plants each year for the Christmas market, while the U.S. as a whole chums out a staggering 40 million plants!

As a visitor to the U.S., this poinsettia craze piqued my curiosity, I had not observed such ebullience for poinsettia in my native New Zealand. I found myself wondering why poinsettia was associated with Christmas. Where did this plant come from? Does poinsettia have any historical interest? Who was Joel Poinsett, the accredited discoverer of poinsettia? After a bit of library work and a worldwide survey of herbaria, I found some fascinating facts, and thought that poinsettia growers, retailers, and purchasers may like to know a bit more about the cultural history and people associated with this plant.

Poinsettia (Euphorbia pulcherrimo.) is native to southwestern Mexico and Guatemala where it grows in rocky canyons. The plant was cultivated and valued by the Aztecs and Mayans well before the arrival of Europeans. The Aztecs called poinsettia cuetlaxochitl (brilliant flower) and the Mayans referred to it as k'alul wits (ember flower). These indigenous peoples had a variety of aesthetic, practical, and medicinal uses, as well as magical beliefs for poinsettia.

Aztecs applied the milky white sap to the breasts of women to increase milk production by nursing mothers and wet nurses. Sap was also used as a depilatory, and the bark and red bracts were used to make a reddish-purple dye. Cuetlaxochitl could induce magical ailments in women. Sitting on, stepping over, or smelling cuetlaxochitl, would cause infection of female reproductive organs, and merely looking at the red bracts would cause a pregnant woman's child to be born crosswise! Despite the seemingly undesirable magical properties, the Aztec caciques, Netzahualocoyotl and Montezuma valued cuetlaxochitl highly, believing the plant with its red bracts symbolized purity.

Mayan uses for k'alul wits still persist today amongst the Teenek Indians in southeastern Mexico. Teeneks use the plant to decorate gardens and cultivate it for medicinal uses. When k'alul wits is flowering, the yellow inflorescence and red bracts are boiled and administered to women as a remedy for either obstetrical or gynecological hemorrhaging. For both women and men, the adverse effects of snakebites can be relieved by boiling and drinking the root.

Poinsettia was first associated· with Christian celebrations in the 17th century. Franciscan priests in southern Mexico used the red and green foliage of flowering poinsettia to decorate pesebre, elaborate nativity scenes. Red and green are traditional Christmas colors, and their association with the birth of Christ has been carried over from ancient pagan rituals. Homes were customarily decorated with evergreen foliage when mid-winter pagan festivals were celebrated. Winter evergreens bearing fruit were symbols of the undying life flourishing amongst skeletal deciduous trees. At first, this non-Christian Roman ritual, was condemned by the Church. Gradually, over time, Christian homes and churches became splendidly decorated with greenery at Christmas. In 604 AD, Pope Gregory I, officially sanctioned the use of evergreens to ornament Christmas festivities. Holly, with its prickly dark green foliage and bright red berries became associated with Mary and the subsequent birth and crucifixion of Christ Later, by virtue of its winter colors, and in keeping with ancient tradition, flowering poinsettia was a logical choice as a decoration for new world Christmas celebrations.

Poinsettia was introduced into the U.S. after 1825 {the exact date is unknown) by Joel Roberts Poinsett, a native of Charleston, South Carolina. Poinsett has a fascinating history, and some of his exploits are well worth discussion. Born in 1779 to wealthy parents of Huguenot descent, he was educated in Britain, became proficient at languages (having command of five; French, Spanish, Italian, German and Russian), and displayed a strong interest in botany and the arts. While abroad, Poinsett received extensive military training and found the army lifestyle much to his liking. He returned to the U.S. in 1800 after completing his schooling. At the age of 22, Poinsett left South Carolina and embarked on a European tour. For the next eight years his refined social skills, charisma and "lively mind" earned him favor with Tsar Alexander of Russia. He spent considerable time socializing with the Russian elite in the court of the Tsar in St. Petersburg, and participated in Russian reconnaissance during the Franco-Russian conflict. In 1808, Poinsett left Russia to spend time in France, and met with Napoleon before returning to the U.S. in 1809.

Political troubles in South America in 1810 attracted the attention of the U.S. government. Poinsett, who was applying for a military position in Washington, was dispatched by President Madison on a covert operation to promote and protect the commercial interests of the U.S. . The Chilean civil war of 1814 that Poinsett helped orchestrate was quashed by government forces. The British who had interests in Chile sought to counteract Poinsett's revolutionary actions. The British navy trapped the ship that was to carry Poinsett back to the U.S. in a Chilean harbor. A sea battle followed and the crew was captured and taken back to the U.S .. Poinsett however, was left stranded on the coast of Chile. The British refused to return "England's archenemy" to America while the two countries were still at war. Poinsett managed to cross the Andes into Argentina and fled secretly back to the U.S. on a Portuguese ship in September 1814.

After a period of domestic politics in both the South Carolina legislature and Congress, Poinsett accepted President John Quincy Adams' offer to be the first U.S. minister to Mexico in 1825. Poinsett was given three policy objectives to pursue in Mexico: acquire Texas from Mexico; prevent Mexico seizing Cuba from Spain; and reduce British influence in Mexico. As a consequence of this foreign policy, Poinsett became very unpopular. Both the government and the general populace demanded Poinsett's removal from Mexico. President Jackson authorized the recall, and Ambassador Poinsett returned to Washington in March 1830.

Surprisingly, during this stormy period in Mexico, Poinsett found time to pursue his interest in botany, and sent specimens of Euphorbia pulcherrima (poinsettia, named in Poinsett's honor), red and yellow mimosa, and Mexican Rose, (a species of Hibiscus) to his estate in Greenville, South Carolina. Poinsettia was propagated at Greenville and distributed to horticulturally minded friends and botanical gardens throughout the U.S.. It should be mentioned here that Poinsett's achievements in areas other than the military and politics were considerable, in particular, his support for the use of science to improve agricultural production.

In South Carolina, Poinsett promoted crop rotation (alternating rice crops with hemp, clover or peas), use of guano as fertilizer, and envisioned agricultural diversification (silk, flax, cork and olive production) as an economic remedy for declining cotton profits. Viticulture was of particular interest. Poinsett had studied grape cultivation in France, Italy, Switzerland, and the Madeira Islands. He believed the grape would be a profitable enterprise for the South.

Poinsett served as Secretary of War (1837-1841) under President Martin Van Buren. At the end of his tenure, Poinsett was elected president (1841- 1845) of the newly formed National Institute for the Promotion of Science which was set up to utilize funds bequeathed by the Briton, James Smithson ($500,000 was paid into the U.S. treasury in 1838), to found "an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men." Support for the National Institute for the Promotion of Science languished, and it was superseded in 1846 when Congress drafted a bill for the establishment of the Smithsonian Institute with Smithson's benefaction.

After 1841 Poinsett retired from politics and resided in South Carolina with his wife Mary Pringle. Poinsett, the last of the South Carolinian lineage, passed away in 1851 at the age of 72. He had suffered from tuberculosis for most of his life and complications led to an incurable case of pneumonia. An apartment house in Charleston, and a hotel and cotton mill in Greenville bear his name, yet Poinsett has gained a greater degree of immortality from the plant known to many worldwide as poinsettia.

As an advocate of using science to improve agriculture, Poinsett, would undoubtedly have been delighted with the attention Euphorbia pulcherrima (poinsettia) has received from the scientific community. Poinsettia has been the subject of considerable research effort from horticultural scientists and plant breeders interested in making it an attractive commodity, and from entomologists interested in controlling insects that feed on the plant.

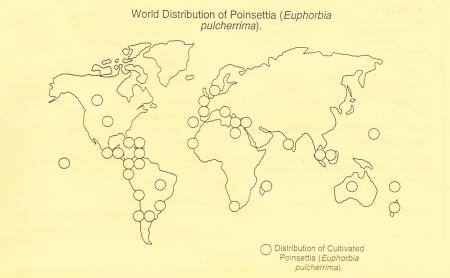

I sent a questionnaire to 76 herbaria in various countries and it revealed that poinsettia is grown globally for Christmas celebrations. Some wonderful names have evolved to describe the striking appearance of poinsettia and its association with Christmas. I have put the most interesting of these in Table 1 and the accompanying map shows the cultivated distribution of poinsettia. The plant has also established in the wild in several countries outside its natural range. Presumably it has escaped from gardens, when viable seed has been blown into areas suitable for establishment. Little is known about the pollination ecology of poinsettia, but it is thought that hummingbirds are probably responsible for pollination as bees are unable to see red.

During Christmas, when you are either growing or enjoying decorative displays of poinsettia, a few of the points discussed in this essay may spring to mind, and poinsettia-mania in November and December may not seem so bizarre. After all, the contemporary Christmas phenomenon associated with this plant is part of a cultural history that dates back to the Aztecs and Mayans. Who knows what the status of this plant will be in another 300 years, maybe the sticky white sap will be the source of a miracle cancer pharmaceutical.

Table 1. The distribution and vernacular names of poinsettia: Results from a worldwide herbaria survey.

| Country | Naturalized? | Commericalized? | Vernacular Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | Yes | Yes | Estrella Feder |

| Bermuda | No | Yes (outdoor ornamental) | Burning Bush |

| Brazil | Yes | Yes | Red Parrot Beak |

| Canary Islands | No | Yes (outdoor ornamental) | Xmas Star |

| Colombia | Yes | No | Navidad |

| France | No | Yes | Euphorbe de Noel |

| Greece | No | Yes | Aegyptios |

| Guatemala | Yes (native) | Yes | Hoja de Pascua |

| Guyana | No | Yes | Xmas Flower |

| Mexico | Yes (native) | Yes | Noche Buena |

| Philippines | No | Yes | Mexican Flame Leaf |

| Solomon Islands | Yes | No | Xmas Star |

| Spain | No | Yes | Flores de Pascua |

| Surinmae | No | No | Kerstster |

| Thailand | No | Yes | Tont Xmas |

| Trinidad & Tobago | No | Yes | Xmas Tree |

| Turkey | No | Yes | Ataturk's Flower |