A monthly e-newsletter from UMass Extension for landscapers, arborists, and other Green Industry professionals.

To read individual sections of the message, click on the section headings below to expand the content:

Hot Topics

UMass Garden Calendar Photo Contest

Ever take a great garden photo and think “this would be perfect for the UMass Garden Calendar?” We are pleased to announce that we are now accepting photos submitted by the public. Submissions will be judged by the calendar team at UMass Extension and may earn a spot in the 2019 Garden Calendar. For more information visit the Garden Calendar page.

Ticks are active at this time!

Remember to take precautions when working outdoors and to conduct daily tick checks. The UMass Amherst Laboratory of Medical Zoology tests ticks for Lyme Disease and other tick-borne pathogens. Visit the Tick Report website for more information.

Questions & Answers

Q: I have noticed that purple leaved plum, along with other trees, seems to be being killed by a moss growing on them. I’m concerned about the purple leaved plum in my yard and am wondering can I do to prevent this?

A: The "moss" is actually a lichen. These moss-like lichens seen growing on trees and shrubs in the Northeast are not parasitic. Lichens are complex lifeforms made up of two different organisms: a fungus and an alga. The organisms have a symbiotic relationship in which the fungus provides water, minerals, and shelter to the alga and the alga uses photosynthesis to produce food utilized by the fungus. The lichens attach to hard surfaces where there is a conducive environment for them, which includes sunlight, water and good air quality. Fruticose lichens are the ones that resemble mosses; other growth types include foliose and crustose lichens, which are often found growing on tree trunks. Fruticose lichens are frequently found on trees and shrubs with poor growth or that are dead; therefore, these lichens are often associated with the decline or death. However, they are simply there because of the access to sunlight provided by thin canopies or dead limbs. This makes the presence of lichens a good indicator of poor growth and an unhealthy plant.

The purple leaved plum, Prunus cerasifera, is a tree commonly seen with heavy fruticose lichen growth. Purple leaved plum is a short-lived species, approximately 20 years. As these trees approach their lifespan or surpass it, they often have very poor vigor and growth, resulting in a suitable place for lichens to grow. So, the next time you see a purple leaved plum covered in lichens, a good question might be how old is it?

In many areas of Massachusetts, particularly the southeast, trees have been exposed to a continual onslaught of stresses, including winter moth, gypsy moth, gall wasp, and drought. These stresses have resulted in widespread poor health and thin canopies which provides suitable habitat for lichens to grow, leading to large areas of trees heavily colonized with lichens. These are not the only causes of heavy lichen growth, but some common examples. The next time you see a tree or shrub with heavy lichen growth in the crown, it should trigger an investigation into the root cause; this is the only effective way to manage lichen growth and proliferation. A vigorous healthy tree or shrub typically does not support extensive fruticose lichen growth due to shade from the foliage.

Q: Why did my hawthorn tree defoliate about a month earlier than normal?

A: Pre-mature defoliation can be related to several issues, including foliar disease or stress. Hawthorns (Crataegus spp.) are susceptible to a couple of different foliar diseases that may cause pre-mature defoliation. The two primary foliar disease suspects would be rust or leaf spot. Cedar-hawthorn rust is similar to cedar apple rust, having a lifecycle that has two hosts: cedar (really Juniperus) and hawthorn (Crataegus), among others. Spores are released from Juniperus hosts and then land on and infect hawthorn leaves. Lesions on leaves are typically bright yellow, making it easily distinguishable. In years with lots of precipitation, such as this past spring/early summer, this results in enough disease to potentially cause premature defoliation.

Another possibility is hawthorn leaf spot. This leaf spot overwinters on dropped leaves and causes the initial infections in the spring. Leaf lesions typically include red and purple colors. Initial infections develop more spores that are released and can cause additional infections throughout the growing season. Disease can build up rapidly during wet growing seasons, resulting in premature defoliation. For more information about identifying these diseases and possible management see the following fact sheets.

UMass Extension cedar hawthorn rust fact sheet

UMass Extension cedar leaf spot fact sheet

Foliar diseases are not the only causes of premature defoliation. Other factors can contribute to premature defoliation, especially environmental or pest related stresses. These conditions would require further investigation to identify the causal factors.

Russ Norton, Agriculture & Horticulture Extension Educator, Cape Cod Cooperative Extension

Trouble Maker of the Month

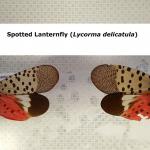

Spotted Lanternfly: Report it if Found

The spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula), also known as a lanternmoth, is neither a fly nor a moth! This insect is a member of the Order Hemiptera (true bugs, cicadas, hoppers, aphids, and others) and the Family Fulgoridae, also known as planthoppers. This insect is a non-native species first detected in the United States in Berks County, Pennsylvania and confirmed on September 22, 2014. The spotted lanternfly is not currently found in Massachusetts. (Let’s keep it that way!)

Where did it come from?

The spotted lanternfly is considered native to China, India, and Vietnam. It has been introduced as a non-native insect to South Korea and Japan, prior to its detection in the United States. In South Korea, it is considered invasive and a pest of grapes and peaches. A 2014 United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) bulletin states that the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture found significant populations of the spotted lanternfly at multiple properties at the time of its detection, including residential properties and a commercial property with a specialty stone business. That particular company had imported over 150 shipments from China, India, and Brazil annually, according to the USDA APHIS bulletin.

What host plants does it impact?

The spotted lanternfly has been reported from over 70 species of plants, including the following:

- Tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima)

- Apple (Malus spp.)

- Plum, cherry, peach, apricot (Prunus spp.)

- Grape (Vitis spp.)

- Pine (Pinus spp.) and others

Adults are found on tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) which is an invasive plant. In the fall in Pennsylvania, adult spotted lanternfly prefer to feed, mate, and lay eggs on tree of heaven when compared to other host plants. That being said, proximity to tree of heaven did not significantly influence the number of spotted lanternfly found on other hosts in a 2015-2016 host plant evaluation conducted in PA. After spending time on tree of heaven, the insects disperse in the local area to lay eggs just about anywhere.

Other hosts reported for this insect include: Maple (Acer spp.), serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis), black birch (Betula lenta), paper birch (Betula papyrifera), pignut hickory (Carya glabra), dogwood (Cornus spp.), American beech (Fagus grandifolia), white ash (Fraxinus americana), black walnut (Juglans nigra), tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera), black gum (Nyssa sylvatica), American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis), big-toothed aspen (Populus grandidentata), black cherry (Prunus serotina), oak (Quercus spp.), willow (Salix spp.), sassafras (Sassafras albidum), Japanese snowbell (Styrax japonicus), American linden (Tilia americana), and slippery elm (Ulmus rubra).

What does the insect look like?

Adults are 1 inch long and ½ inch wide at rest. The forewing is gray with black spots of varying sizes and the wing tips have black spots outlined in gray. Hind wings have contrasting patches of red and black with a white band. The legs and head are black, and the abdomen is yellow with black bands. Early instars (immature stages; 1st, 2nd, and 3rd instar) are black with white spots. By the last immature stage, the 4th instar, they develop red patches. This is the last immature stage before they mature into an adult. Both the immature insect and the adult are quite visually striking. Adults are especially so when they have been startled and expose the bright red coloration on the hind wings. When the adult is at rest, particularly on the trunk of the tree of heaven, their gray, spotted color may actually cause them to blend in with their surroundings. Fresh egg masses appear as if coated with gray mud which, as they age, takes on a dry/cracked appearance. Very old egg masses may look like rows of 30-50 brown seed-like structures aligned vertically in columns. New egg masses may look like “weird gypsy moth egg masses”, but they are not.

What signs and symptoms can I look for?

The adults and immatures of this species damage host plants by feeding on sap from stems, leaves, and the trunks of trees. In the springtime in Pennsylvania (late April - mid-May) nymphs (immatures) are found on smaller plants and vines and new growth of trees and shrubs. Third and fourth instar nymphs migrate to the tree of heaven and are observed feeding on trunks and branches. Trees may be found with sap weeping from the wounds caused by the insect’s feeding. The sugary secretions (excrement) created by this insect may coat the host plant, later leading to the growth of sooty mold. Insects such as wasps, hornets, bees, and ants may also be attracted to the sugary waste created by the lanternflies, or sap weeping from open wounds in the host plant. Host plants have been described as giving off a fermented odor when this insect is present.

Adults are present by the middle of July in Pennsylvania and begin laying eggs (as described above) by late September and continue laying eggs through late November and even early December in that state. Adults may be found on the trunks of trees such as the tree of heaven or other host plants growing in close proximity to them. The USDA states that dusk is a great time to inspect your trees or other host plants for signs of this pest, as the insects tend to gather in large groups on the trunks and stems of plants at that time of day.

Tree of heaven, bricks, stone, lawn furniture, recreational vehicles, and other smooth surfaces can be inspected for egg masses. Egg masses laid on outdoor residential items such as those listed above may pose the greatest threat for spreading this insect via human aided movement.

What is the timing of its life cycle?

This insect has not been found in Massachusetts at this time and therefore the timing of its life cycle may be unclear. As with most insects, the timing of their life cycle can vary slightly given local temperatures. The following information is based on observations reported from Pennsylvania.

There is one generation per year. Spotted lanternfly eggs are the stage that overwinter. In Pennsylvania, these eggs hatch sometime in May and nymphs (immatures) undergo four instars. 1st, 2nd, and 3rd instars are black with white spots. These immatures will feed on the various host plants listed above, depending upon availability. In PA, these early instars have been found to move up and down the host plant on a daily basis as they feed. This makes capturing some of them with sticky bands placed around host plants such as tree of heaven possible. Older spotted lanternfly do not tend to be captured by that technique. The final immature stage, the 4th instar, develops red patches over these black and white spots and are typically present in July in PA.

Within the same month, these 4th instar nymphs develop into adults, which have been described as weak fliers, although they have wings. As you would suspect from a planthopper however, they are capable of jumping and may use their wings to aid them while doing so. Adults may gather in large numbers. In the fall in PA, the adults are frequently found on tree of heaven. The adult female spotted lanternfly lays brown/tan, seed-like eggs in rows on host plants and other smooth surfaces. These rows are often oriented vertically, and then covered with a gray, waxy secretion from the female (it is white when first secreted, and then quickly turns gray-brown in color). Sometimes the eggs are completely covered by this substance, other times they are not. Each mass can contain 30-50 individual eggs, and researchers in PA believe each female lays at least 2 of those masses each season. As the egg mass ages, the gray waxy coating cracks and looks even more like dried mud. Eggs are laid starting in September and this can continue through late November or early December in PA. Eggs overwinter, hatch in May, and the life cycle continues. Based on observations from Pennsylvania, eggs can be found, if this insect is present, between October and May.

Where is it now?

This insect has not yet been detected in Massachusetts at this time.

Spotted lanternfly is currently known to the following counties in Pennsylvania: Berks, Bucks, Carbon, Chester, Delaware, Lancaster, Lebanon, Lehigh, Monroe, Montgomery, Northampton, Philadelphia, and Schuylkill County. For a map of the locations, visit the updated Spotted Lanternfly Quarantine Map: (http://www.agriculture.pa.gov/Plants_Land_Water/PlantIndustry/Entomology/spotted_lanternfly/quarantine/Documents/Lycorma%20Quarantine%20Map%20(Statewide%20View).pdf). Certain municipalities within those Pennsylvania counties are subject to a quarantine created by the PA Dept. of Agriculture. Their quarantine, in an effort to stop the risk of human aided spread of this insect, has restricted the movement of certain articles out of towns where this insect has been detected, including brush, debris, or yard waste, landscaping or construction waste, logs, stumps, firewood, nursery stock, and outdoor residential items such as recreational vehicles, tractors, tile, stone, etc. For more information regarding Pennsylvania's quarantine, visit the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture (link is external).

Until November, 2017, this invasive insect was only known to Pennsylvania. It has now been reported from Delaware (November 20, 2017) and New York (November 29, 2017). The Delaware Department of Agriculture announced the finding of a single female spotted lanternfly in New Castle County in the Wilmington, Delaware area. At this time, officials in Delaware note that it is unclear if this individual was an accidental hitchhiker, or evidence of an established population in the state. For more information about the find in Delaware, visit: https://news.delaware.gov/2017/11/20/spotted-lanternfly-confirmed-delaware/. The New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets reported on November 29, 2017 the finding of a single dead individual spotted lanternfly in the state from earlier in the month. A single dead specimen was confirmed at a facility in Delaware County, New York, which is located south-west of Albany. The NYS Dept. of Agriculture and Markets states that this dead individual may have come in on an interstate shipment. For more information about the find in New York, visit: https://www.agriculture.ny.gov/AD/release.asp?ReleaseID=3637.

Where can I find more pictures and information?

The Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture:

http://www.agriculture.pa.gov/protect/plantindustry/spotted_lanternfly

PennState Extension:

https://extension.psu.edu/spotted-lanternfly-what-to-look-for

https://extension.psu.edu/spotted-lanternfly-identification-and-life-cycle

https://extension.psu.edu/spotted-lanternfly-biology

https://extension.psu.edu/spotted-lanternfly-host-study

The United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service:

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/publications/plant_health/2014/alert_spotted_lanternfly.pdf

Massachusetts Introduced Pests Outreach Project and Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources:

https://massnrc.org/pests/pestFAQsheets/spottedlanternfly.html

*To request free spotted lanternfly ID cards, visit: http://bit.ly/FPOMOrder

Whom do I contact if I suspect spotted lanternfly?

You can report a suspected spotted lanternfly encounter in Massachusetts in many ways. These include but may not be limited to:

UMass Extension’s Landscape, Nursery, and Urban Forestry Program:

E-mail a photo of the insects, egg masses, or suspected damage to: greeninfo@umext.umass.edu or call 413-545-0895. You may also contact Tawny Simisky, Extension Entomologist specializing in Woody Plant Entomology at 413-545-1053 or tsimisky@umass.edu.

Massachusetts Introduced Pests Outreach Project:

Report pest sightings: https://massnrc.org/pests/report.aspx

Center for Agriculture, Food, and the Environment at UMass Amherst:

E-mail a photo of the insects, egg masses, or suspected damage to: ag@cns.umass.edu or call 413-545-4800.

Plant of the Month

Ginkgo biloba, maidenhair tree

Brilliant yellow fall foliage makes Ginkgo biloba an excellent choice for fall interest. Although, be sure to appreciate the foliage while you can, as a hard frost will cause almost all leaves to fall in a single day. Often described as a ‘living fossil’, Ginkgo biloba has remained essentially unchanged for around 200 million years. This unique tree is not closely related to any other living plant, being in its own genus, family, order, and subclass.

Ginkgo biloba is a large, deciduous tree native to China that grows 40-80’ and 30-40’ wide (can reach up to 100’). Plants have a pyramidal shape when young with branches spreading with age. The bright green leaves are triangular to fan shaped and are generally notched at the apex creating two lobes (the species name – biloba – is a reference to the lobed leaves). Leaves are on spurs in clusters of 3-5. Ginkgo biloba has excellent bright to golden yellow fall color. Trees are dioecious, meaning there are separate male and female plants. Female trees produce a light orange to tan fruit that resembles an apricot. Male trees should be planted as the fruit has a horrible smell (female trees are outlawed in same areas of the US). Trees will not flower or fruit until they are 20 years old or more, so care should be taken to purchase male cultivars. Bark is grey to brown and becomes deeply ridged or fissured with age.

Ginkgo biloba has no serious insect or disease problems, making it a great specimen, lawn shade tree, or street tree. Trees are best planted in well-drained soil in full sun. It is tolerant of a wide range of soils from alkaline to acidic and adapts well to urban environments.

Many cultivars are male-forms. ‘Autumn Gold’ matures to 40-50’ and has golden yellow fall color. ‘Princeton Sentry’ is a popular male cultivar growing to 60’ tall but is more narrow, growing to around 25’ wide. ‘Jade Butterflies’ is a dwarf male form that grows to only 4-12’ tall over 10 years. Its common name comes from the deeply bi-lobed leaves that looks like green butterfly wings. There are a variety of cultivars in the Pendula Group that vary from dwarf, slow growing cultivars to cultivars with branches that slightly droop, and more umbrella-shaped forms. ‘JN9’, commonly sold by the trade name Sky Tower, is a compact upright cultivar maturing to 15-20’ tall and only 6-10’ wide.

Mandy Bayer, Extension Assistant Professor of Sustainable Landscape Horticulture, University of Massachusetts Amherst

Upcoming Events

New England Grows

New England GROWS takes place on November 29 - December 1, 2017, at the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center. For the latest information, download the GROWS mobile app; follow New England GROWS on Facebook and Twitter; visit NewEnglandGrows.org or call (508) 653-3009.

GROWS Marketing Guide: http://tinyurl.com/GROWSBrand17

Other Upcoming Events:

- 11/29-12/1: New England Grows

- 1/8-2/16: UMass Winter School for Turf Managers

For more information and registration for any of these events visit the UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, and Urban Forestry Program Upcoming Events Page.

Additional Resources

For detailed reports on growing conditions and pest activity – Check out the Landscape Message

For commercial growers of greenhouse crops and flowers - Check out the New England Greenhouse Update website

For professional turf managers - Check out Turf Management Updates

For home gardeners and garden retailers - Check out home lawn and garden resources. UMass Extension also has a Twitter feed that provides timely, daily gardening tips, sunrise and sunset times to home gardeners, see https://twitter.com/UMassGardenClip

Diagnostic Services

A UMass Laboratory Diagnoses Landscape and Turf Problems - The UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab is available to serve commercial landscape contractors, turf managers, arborists, nurseries and other green industry professionals. It provides woody plant and turf disease analysis, woody plant and turf insect identification, turfgrass identification, weed identification, and offers a report of pest management strategies that are research based, economically sound and environmentally appropriate for the situation. Accurate diagnosis for a turf or landscape problem can often eliminate or reduce the need for pesticide use. For sampling procedures, detailed submission instructions and a list of fees, see Plant Diagnostics Laboratory

Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing - The University of Massachusetts Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory is located on the campus of The University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Testing services are available to all. The function of the Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory is to provide test results and recommendations that lead to the wise and economical use of soils and soil amendments. For complete information, visit the UMass Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory web site. Alternatively, call the lab at (413) 545-2311.