A monthly e-newsletter from UMass Extension for landscapers, arborists, and other Green Industry professionals, including monthly tips for home gardeners.

To read individual sections of the message, click on the section headings below to expand the content.

To print this issue, either press CTRL/CMD + P or right click on the page and choose Print from the pop-up menu.

2024 UMass Garden Calendar

Purchasing plants for the landscape can be a considerable investment of both time and money. Selecting the right plant for the right place is the first step in making the most of this investment. This means selecting the best-suited plant material for your location according to light exposure, water availability, hardiness zone, soil conditions, and environmental exposure. The next step, and just as important to success, is following proper planting procedure.

Our 2024 calendar includes guidelines for preparing the planting hole, avoiding problems with circling roots, amending the soil before planting, and shares the results of a two-year UMass study looking at plant establishment success using different root preparation methods at planting.

UMass Extension works with the citizens of Massachusetts to help them make sound choices about growing, planting, and maintaining plants in our landscapes, including vegetables, backyard fruits, and ornamental plants. Our 2024 calendar continues UMass Extension’s tradition of providing gardeners with useful and practical information. Many people also love the daily tips and find the daily sunrise/sunset times highly useful!

Show your clients that you appreciate their business this year! Special pricing is available on orders of 10 copies or more.

COST: $14.50; shipping is FREE on orders of 9 or fewer calendars - FREE SHIPPING ENDS NOV 1! (Note: There is no free shipping on bulk orders of 10 or more.)

FOR IMAGES IN THE CALENDAR, details, and ordering info, go to https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/publications-resources/umass-extensions-garden-calendar.

As always, each month features:

- An inspiring garden image.

- Daily gardening tips for Northeast growing conditions.

- Daily sunrise and sunset times.

- Phases of the moon.

- Plenty of room for notes.

- Low gloss paper for easy writing.

Hot Topics

Late Summer In Massachusetts – It’s a Waspy Business

I get calls from people about insects or ticks on a year round basis. People may take note of a large paper nest in a shrub or on the eave of their house. Also some people find that they cannot sit outside to enjoy food or a beverage without a confrontation with yellowjackets. The question is “what is going on and how does it get fixed?”

OK, let’s start with those football shaped nests. Those are bald-faced hornets, actually a type of yellowjacket. While you may just notice them now, those nests were actually initiated last April/May. These hornets are about 1 inch long with black and white coloration and very defensive attitudes. I generally tell people that if they can just give them space until the fall, new queens will be produced and they leave to find a place to overwinter, typically under tree bark. The remaining workers will die from starvation or first frost. The nest is not reused.

OK, let’s start with those football shaped nests. Those are bald-faced hornets, actually a type of yellowjacket. While you may just notice them now, those nests were actually initiated last April/May. These hornets are about 1 inch long with black and white coloration and very defensive attitudes. I generally tell people that if they can just give them space until the fall, new queens will be produced and they leave to find a place to overwinter, typically under tree bark. The remaining workers will die from starvation or first frost. The nest is not reused.

But what if the nest is in a shrub where people could get too close? There are two options to consider. For brave do-it-yourselfers, there are wasp and hornet sprays that shoot about 20 feet. I recommend doing this at night when the hornets are all back in the nest. Professional pest control companies can also treat and remove the nest.

Similarly, yellowjackets initiated nests last spring. Queens start nests underground, usually in an abandoned rodent burrow. Nests are at their peak now with about 400 workers. From spring up to about this point in the fall, they have been hunting insect prey to feed their kids (larvae). Prey are less abundant now but they are really looking for sugar, which could be from the soda you might be drinking or mature fruits like tomatoes, apples, grapes, etc.

Again, if you know where the nest is and can avoid it, great. But many times nests might be under a set of stairs or the edge of a shed. Some people are highly sensitive to the sting of a yellowjacket. They are responsible for most of the stinging deaths in the US.

We also have European hornets. They look like a very large yellowjacket and mostly nest in tree cavities. About four years ago when the “murder hornets” were found in Washington state, I immediately started receiving calls…these were all European hornets. Murder hornets, or Asian giant hornets, are formidable, being about 2 inches long with a quarter inch long stinger! They will never take up residence in Massachusetts, as their natural habitat is temperate rain forests. Click here to see other common "murder hornet" look-a-likes.

We also have European hornets. They look like a very large yellowjacket and mostly nest in tree cavities. About four years ago when the “murder hornets” were found in Washington state, I immediately started receiving calls…these were all European hornets. Murder hornets, or Asian giant hornets, are formidable, being about 2 inches long with a quarter inch long stinger! They will never take up residence in Massachusetts, as their natural habitat is temperate rain forests. Click here to see other common "murder hornet" look-a-likes.

As I always tell people, every creature has a place in this ecosystem. Yellowjackets and hornets are highly beneficial because of the amount of other insects they consume.

Larry Dapsis, Cape Cod Extension Entomologist

Trouble Maker of the Month

Weeds: “Summer Getaways” That Might Obstruct Your R&R!!!!

Each spring, landscape and turf professionals might start the growing season with renewed expectations that this will be the year for better performance from their weed management efforts. As the growing season wears on, professionals are able appreciate whether their renewed expectations were realistic or just simply wishful thinking. The “oh, yeah” versus “oh, no” realization is often more profound in those growing seasons that seem to be a bit more challenging, such as the one we have had 2023.

Traditionally, preemergence herbicide applications are made to turf and landscape areas in the spring for the control of summer annual grassy weeds such as large and smooth crabgrass, goosegrass, yellow foxtail and barnyardgrass. A quick review of product labels shows that these herbicide products also control numerous annual and perennial broadleaf weeds that are germinating from seed. Preemergence herbicides are applied in the spring prior to the germination of annual grassy weeds.

The most common herbicides used for annual grass control in landscape and turf are dithiopyr, pendimethalin, and prodiamine. These active ingredients have the same mechanism of action and are classified as Group 3 herbicides by the Weed Science Society of America. Group 3 herbicides bind to the major microtubule protein known as tubulin. The herbicide-tubulin complex inhibits the polymerization of the tubule on the other end, leading to a loss of microtubule structure and function. As a result of the loss of microtubule structure and function, the spindle apparatus is absent, thus preventing the alignment and separation of chromosomes during mitosis. Microtubules also function in cell wall formation and the inhibition of microtubules prevent the cell wall from forming. These herbicides may cause observed swelling of root tips as cells in this region neither divide nor elongate. More simply stated, the Group 3 herbicides inhibit cell division and the ability of a plant to grow.

Group 3 herbicides for landscape and turf are available as on-fertilizer or sprayable formulations. Regardless of the formulation, the overall performance of these products is increased if a few key best management practices (BMPs) are implemented, as follows:

- After application, the herbicide needs to be watered in to be active and have herbicidal properties.

- While the herbicide needs to be watered in to be active, excessive irrigation in the presence of warm soils will increase herbicide degradation and decrease their level of performance.

- Applications need to be made at the correct time in the spring. Sometimes warm weather in the spring will make people nervous and result in a preemergence herbicide application that is earlier that needed. Applications made earlier than needed are more vulnerable to microbial degradation, which over time effectively decreases the amount of herbicide available to do the job. Remember “early down, early gone.” Another thing to beware of is, if you are using an on-fertilizer formulation, you will need to be aware of how such applications are related to 330 CMR 31.00 (An Act Relative to the Regulation of Plant Nutrients). The regulations promulgated by 330 CMR 31.00 establishes standards for applications of plant nutrients to agricultural land and non-agricultural turf and lawns. A key aspect of the regulation as it relates to turf is that “no applications of plant nutrients shall be made to drought dormant, cold dormant, inactive or otherwise brown turf.”

- Herbicides with a long half-life will provide control longer than those with a shorter half-life. For common herbicide active ingredients, trade names, and typical half-life values - see Table 1.

| Active ingredient | Trade names | Typical herbicide half-life |

| Dithiopyr1 | Dimension 2EW, Dimension Ultra 40WP, Dithiopyr 40 WSB, and several on-fertilizer formulations | 17 days when applied as an EC, 3 to 49 days across 14 turf sites representing diverse climes, soil textures and irrigation regimes. |

| Pendimethalin1 | Pendulum Aquacap, LESCO PRE-M, and several on-fertilizer formulations | 44 days in field studies, varies with soil temperature and moisture. |

| Prodiamine1 | Barricade 4FL, Lesco Stonewall 4L, Proclipse 65 WDG, Primera One Prodiamine 4L, and several on-fertilizer formulations | 120 days, 69 days for a sandy loam in Georgia on a turf site. |

| 1 Active ingredients labeled for both turf and landscape. | ||

Preemergence herbicides preform best when BMPs related to their use are followed. However, even when this occurs there are a few weed species that might sneak by and become your “summer getaways.” The most likely “summer getaways” in turf and landscapes are spotted spurge (Euphorbia maculata or Chamaesyce maculata), rhombic copperleaf (Acalypha rhomboidea), common purslane (Portulaca oleracea), and yellow woodsorrel (Oxalis stricta). Yellow woodsorrel, while being a perennial weed in warmer climates, usually behaves as a summer annual weed in New England. Unlike crabgrass that has most of its germination occur in a large, early season flush, these “summer getaways” germinate a bit later in the growing season. Their germination period occurs when the herbicide than was applied earlier in the season may be starting to wane a bit. These species can be effectively managed by adopting some additional turf and landscape weed management strategies.

Additional management strategies for managing “summer getaways” on sites where you know they are often problematic are as follows:

Landscape:

1. Apply a spring mulch and delay the application of a preemergence herbicide by 3 to 5 weeks. The spring mulch will provide initial control and a delayed preemergence application will provide control as the germination period arrives a little later in the season.

2. Regardless of whether a preemergence herbicide is applied or not, monitor these areas and consider the application of a non-selective herbicide such as glyphosate or glufosinate. Non-herbicide products (acetic acid, clover oil, citric acid) can provide control if weeds are very small.

Turf:

1. Preemergence herbicides with long half-lives will provide better control.

2. Consider a second, split application about 3 to 4 weeks after the initial spring application to reinforce what might be the waning of the first application due to microbial degradation over time.

3. At the first sign of weed escapes, consider the application of a broadleaf herbicide combination product labelled for turf. Common herbicides in these products include 2,4-D, MCPP (mecoprop), dicamba, triclopyr, clopyralid (not for residential turf), and fluroxypyr.

Randy Prostak, UMass Extension Weed Specialist

Q&A

Q. Mowing consumes a lot of time and attention for my business/facility/individual property. What can I do to reduce mowing demands, while still maintaining high quality turf?

A. The capacity of turfgrasses to survive and thrive under repeated defoliation is unique among plants, and mowing is the most fundamental practice employed in the maintenance of turf. While some mowing is necessary, and beneficial, over-doing it can actually be a cause of turfgrass stress and injury.

Research has shown that mowing can make up as much as three quarters or more of total turf management inputs for a given program, and typically comprises around half of all inputs. When considering factors like efficiency, precious time, expensive labor, and carbon footprint, reducing and optimizing mowing is of great interest to many.

Here are some ways to reduce mowing inputs:

- Raise mowing height: Increasing mowing height to the highest level suitable for the grass species present and the primary use of the turf is common advice and nearly always beneficial. For most lawn turf in southern New England, a height of 3-3.5 inches is a good rule of thumb, with irrigated lawns on the lower end and unirrigated lawns best on the higher end. Very simply, the more turfgrass leaf area that is there to conduct photosynthesis, the greater the root mass that each plant is able to support. Roots are the foundation of the turf system, and healthier and more extensive roots means more vigorous and resilient plants and better overall turf performance.

How often mowing is needed (mowing frequency) is a function of cutting height and turfgrass shoot growth rate (more on managing growth rates below). A great guide for mowing frequency is the “1/3 Guideline” (also often referred to as the “1/3 Rule”). This states that no more than 1/3 of the turfgrass shoot height should be removed by a mowing event. For example, if the set mowing height is 3 inches, mowing should occur once the turf reaches 4.5 inches (the 1/3 threshold). This mowing will remove approximately 1.5 inches (1/3 of 4.5) in returning the turf down to 3 inches. A higher height of cut means a higher 1/3 threshold, and therefore promotes longer intervals between mowing events and less mowing over the course of the season.

- Fertilize judiciously, especially as nitrogen (N) is concerned: Among the 18 essential nutrients required by plants, turfgrass growth is most responsive to N. Over the short term, fertilizer applications that contain lots of readily available N (more on N availability and fertilizer programming in the next question in this Q&A) can result in a flush of rapid growth (“surge growth”) that shrinks the mowing interval and accelerates mowing needs.

Over the longer-term, excessive N rates favor vegetative growth (shoot growth) that, on account of finite resources, happens at the expense of root growth. This not only increases mowing needs, but also contributes to a compromised root system that that more broadly impacts turf health.

For more information on fertilizer programming, see Table 12 on page 68 of UMass Extension’s Best Management Practices for Lawn and Landscape Turf:

- Water responsibly: Water is one of our most precious natural resources, and increasing water scarcity threatens availability and increases water costs. Excess moisture can also affect turf health as readily as too little water can. Optimizing water inputs, therefore, is always in our best interest. Dialing in watering with practices like wilt-based irrigation scheduling (withholding irrigation events until the onset of mild moisture stress) not only conserves water, but also promotes more measured growth and less succulent tissues that help to temper mowing demands.

- Employ intelligent turfgrass selection and siting: One of the best investments for reducing mowing and other turfgrass maintenance inputs is careful turfgrass selection… in other words, choosing and planting turfgrass species and varieties well-matched to the growing environment, the intended use of the turf, available management resources, and maintenance objectives. Well-adapted grasses have better inherent performance and require fewer management inputs.

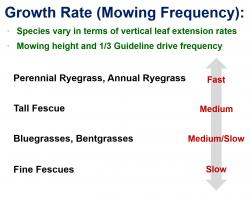

Turfgrass species and varieties can vary considerably in terms of their growth rates (Fig. 1 below), and choosing slower-growing grasses will lower mowing demands. Some species of fine fescues (commonly called “no mow” fescues), for example, grow so slowly that they may only require mowing once or twice a year. These can be excellent choices for areas that are difficult to mow regularly, such as slopes or embankments.

Conduct a site analysis to determine areas best suited for traditional turf surfaces; less conducive areas may be better suited to solutions like no mow fescues, wildflowers/pollinator support, ornamental plantings, hardscapes, naturalized areas, rain gardens, and other appropriate groundcovers. Optimizing use of managed turf areas will promote less mowing and greater mowing efficiency.

Figure 1: Growth rates (and expected mowing frequency) of key cool-season turfgrass species (click to enlarge).

Other mowing optimization tips: In planning and implementing good site design as above, think carefully about what regular mowing activities will look like… aim for sweeping curves and rounded corners, as opposed to steep angles and sharp edges… these are harder to navigate with mowing equipment. Take some time to plan mowing routes… mowing routes that minimize turns will be faster and more efficient, saving time and money. Explore larger mowers that cover ground more quickly, but remember that cost, maintenance, storage, maneuverability, and transport also should be considered. For more sophisticated programs, take a look at plant growth regulators that, when used properly, can slow turfgrass growth rates and extend mowing intervals.

Q . I understand that determining the percentage of slow-release nitrogen in a fertilizer is a central consideration for turf fertilizer programming, but when I look at a fertilizer label, I don’t know how/where to find this information. Can you walk me through it?

A. Fertilizer labels can be frustrating for many novices and experienced turf managers alike. While much important information is present on the typical label, what is often missing is a clear, easy-to-ascertain listing of the percentage of slowly-available N in the material. As mentioned above, slowly-available N content directly influences key fertilizer programming decisions including timing, application rates, application intervals, and materials selection.

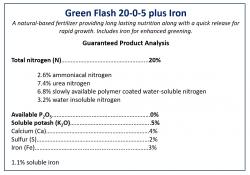

Refer to the following example label (click to enlarge):

Step 1: Find the guaranteed analysis for total nitrogen. In this case, it is 20%, meaning that the material contains 20% N by weight.

Step 2: Find the percentage of water insoluble nitrogen (WIN). WIN is a primary source of slowly available N and includes ureaformaldehyde (UF), isobutylidene diurea (IBDU), and products derived from natural organic materials. WIN content is 3.2% in this example.

Step 3: Find the percentages of any additional sources of slow-release nitrogen (SRN) listed… this often requires careful reading! Ammoniacal N and urea N, both listed on this label, are readily available sources of N and don’t qualify. What we’re looking for are various plastic, polymer, or sulfur-coated technologies that are engineered to modulate the speed of N release and achieve slow-release characteristics. On this label, we have 6.8% slowly available polymer coated water-soluble N.

Step 4: Add together all WIN and SRN content, then divide by total nitrogen to determine the overall slowly available N content of the material:

In this case, it is 3.2% + 6.8% = 10%

10% SRN / 20% total N = 50% SRN

So, 50% of the N in the example fertilizer is slowly available N (SRN). This fertilizer provides a good balance of readily available N for a rapid response, and SRN that meters out slowly over time for an extended response.

As referenced above, Table 12 on page 68 of UMass Extension’s Best Management Practices for Lawn and Landscape Turf features suggested options for timing, rate, and % SRN a for N applications based on number of applications per year.

Jason Lanier, UMass Extension Turf Specialist

Garden Clippings Tips of the Month

September is the month to . . . .

-

Be wary of yellowjackets when working outdoors. Their populations are peaking now while their food sources are dwindling, resulting in more active, aggressive behavior. In addition to their conspicuous forays for alternative food sources in the garden, yellowjackets may also be creating ground nests as the air temperature cools but the soil temperature remains hospitable.

-

Add all sorts of plant materials to the compost pile: flowers and stems deadheaded from perennials, annuals past their prime, spent vegetable plants, and any vegetables overlooked at harvest time. Chop materials into smaller pieces to speed their breakdown. Refrain from incorporating weeds that have gone to seed and diseased/insect infested plants, all of which may cause problems in the finished compost, since the compost pile will likely not get hot enough to destroy them.

-

Check for ripening fruits on apple trees. Apples become softer and sweeter as they ripen, and are ready for picking when they are crisp, firm (but not extremely hard), juicy, and flavorful. Other characteristics of ripening apples may include a color change from green to red and/or yellow, and the presence of brown seeds inside the fruit. Ripe fruits (and their accompanying stems) should detach readily from the tree when given a slight twist and upward lift.

-

Harvest pumpkins and winter squash when their rinds are hard and they have a deep, solid color. Leave a 2 to 3 inch stem on harvested fruit, and cure them for a week to 10 days in a warm (80-85°F), dry location, such as a garden shed, garage, or even outdoors if the weather is conducive. Store cured squash at 50 to 55°F in a dry, airy location.

-

Celebrate National Indoor Plant Week. Professionals in the interiorscaping industry have designated the third week of September as a time to “increase public awareness of the importance of indoor plants and their many attributes” (www.nationalindoorplantweek.com). Use the occasion to pay particular attention to the well-being of existing houseplants or to add new ones through propagation, trading with other gardeners, or shopping at the local garden center.

-

Stop watering amaryllis and place the plants in a cool (50°F) location for about 10 weeks. Cut off the leaves once they have dried up. After 10 weeks, move bulbs to a warmer spot and begin watering again to encourage flowering.

-

Assess perennial borders for late season color. If beds are looking a bit blah, add late-flowering plants such as heleniums, asters, coneflowers, sedums, and Japanese anemones to liven things up.

-

Stop deadheading roses. By letting the last of the roses develop hips (fruits), the plants divert energy from flowering to hardening their stems in preparation for winter.

-

Move seedlings of biennials such as foxgloves and forget-me-nots in the garden. If seedlings have grown in a dense cluster around the base of the parent plants, early September is a good time to carefully dig up and spread those clumps throughout other desired areas.

-

Plant trees, shrubs, vines, and perennials. Fall planting can continue until mid-October. Later plantings may not have time to establish an extensive root system before the onset of cold soil temperatures. Soak soil thoroughly prior to planting if rainfall is sparse and water post-planting as needed until the ground freezes.

-

Reseed bare spots in the lawn or undertake lawn renovations. Cool fall temperatures, plenty of rain, and reduced weed pressure make late summer an ideal time to sow grass seed. Be sure to complete lawn renovations early enough to give grass plenty of time to become established before the arrival of winter.

-

Take advantage of rain-softened soil to pull out Oriental bittersweet, non-native honeysuckle shrubs, Japanese barberry, briars, and other invasive plants.

-

Beat the rush and get a soil test! Fall is the best time to add needed soil amendments such as lime, plus the labs are less busy in the fall so you'll receive your results more quickly. For details, see the UMass Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory web site.

Jennifer Kujawski, Horticulturist

Billbug Phenology and Management in Residential Lawns

Billbugs (genus Sphenophorus, Curculionidae: Coleoptera) are serious pests of turfgrass throughout the US. They can be present and damaging in different turfgrass and crop systems, but mostly prefer grasses (plants family Gramineae), such as warm and cool season turfgrasses, corn etc. In New England, specifically Massachusetts, billbugs are mainly a problem of residential lawns, even though can be present at any turf situation if the grass cut at the low/rough mowing height (~2“), including golf course roughs and sports fields.

Billbugs are challenging pests to manage, and recently, billbugs have become a growing problem in residential lawns in New England. The reasons for the outbreaks are not well understood and are being studied at this point. It is possible that efficacy of current chemical control measures is lower than expected because of incorrect application timing and/or reduced efficacy of the insecticides used. Moreover, the optimal timing for management is usually hard to combine with other pest control applications, making billbug management labor and cost intensive.

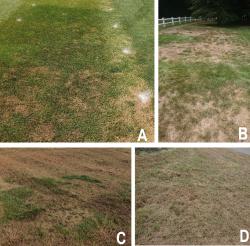

Changing weather patterns affect the grass response and severity of the observable damage. For instance, hot and dry weather in 2020 and 2022 decreased turfgrass tolerance to billbug larvae feeding and many residential lawns had extensive damage (Fig.1 C, D). In 2021 and this year, the damage might not be obvious due to sufficient rainfall that masks the stress; however, the population numbers might be increasing without being noticed and could be problematic next season.

Changing weather patterns affect the grass response and severity of the observable damage. For instance, hot and dry weather in 2020 and 2022 decreased turfgrass tolerance to billbug larvae feeding and many residential lawns had extensive damage (Fig.1 C, D). In 2021 and this year, the damage might not be obvious due to sufficient rainfall that masks the stress; however, the population numbers might be increasing without being noticed and could be problematic next season.

Billbugs are one of the most misdiagnosed pests. Often their damage is attributed to other turfgrass pests: insects, diseases, or even drought damage. Billbugs are stem borers and spend a significant part of their development inside of the plant, and therefore they are not often noticed until the damage is severe and few management options are effective and available.

In the UMass Landscape Entomology Laboratory, we have been monitoring billbug activity since the fall 2019 to better understand their biology, seasonal phenology, and optimal management solutions.

Preliminary data and findings

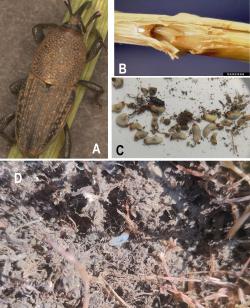

We identified three species present in Massachusetts, the bluegrass billbug (Sphenophorous parvulus), lesser billbug (Sphenophorus minimus), and hunting billbug (Spenophorus venatus). Bluegrass billbugs are the predominant species across the state (Fig. 2); lesser billbugs are less abundant but present in western Massachusetts and their number has been increasing since we started monitoring. Hunting billbugs were found only in the coastal areas (eastern Massachusetts). Hunting billbugs are a notorious pest of warm season turfgrass in the southern regions of the US, but the understanding of this species is limited in our region.

We identified three species present in Massachusetts, the bluegrass billbug (Sphenophorous parvulus), lesser billbug (Sphenophorus minimus), and hunting billbug (Spenophorus venatus). Bluegrass billbugs are the predominant species across the state (Fig. 2); lesser billbugs are less abundant but present in western Massachusetts and their number has been increasing since we started monitoring. Hunting billbugs were found only in the coastal areas (eastern Massachusetts). Hunting billbugs are a notorious pest of warm season turfgrass in the southern regions of the US, but the understanding of this species is limited in our region.

We did not observe drastic differences among these species’ life cycles and phenology. As was described from previous studies, billbugs have a one-year life cycle in our region. They overwinter as adults (Fig. 2 A), emerge at the end of spring, and lay their eggs (Fig 2, B) inside of the grass stems. The young larvae feed inside of the grass and when they grow larger, come out of the stem and feed on the crown (Fig.2 C, D). The most severe damage occurs during the larger larvae feeding period (Fig.1).

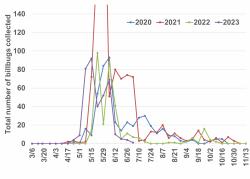

We determined that in western Massachusetts, adult numbers are peaking in late May – early June (Fig. 3). This year (2023), billbug activity, similarly to other pests, occurred about a week earlier, probably because the winter and spring were warmer than usual. We started monitoring the larval activity this year but need to confirm our findings by conducting observations for one or two more seasons. According to this year’s sampling, the first larvae were noticed about a week after adult peak (mid-June), larvae started feeding outside by the end of June, and first damage was noticed in early July. Similarly, during the dry season of 2020, the first observable damage occurred in early July. In August, mostly pupae were found, and in the middle of August we found newly emerged adults. These adults will not produce any more offspring, rather they prepare for overwintering and start finding proper overwintering sites. Several years in a row, we observed that the peak of migration to overwintering sites occurs in early September. During this migration, billbug adults can be found walking on nearby pavement or grass areas. From a management perspective, it is too late to manage this species during their migration. Most of the damage is done and additional damage is not likely; adults are hard to control, especially when they try to hide for the winter. If adults are noticed at this time, the best action is to create a management plan for next season.

We determined that in western Massachusetts, adult numbers are peaking in late May – early June (Fig. 3). This year (2023), billbug activity, similarly to other pests, occurred about a week earlier, probably because the winter and spring were warmer than usual. We started monitoring the larval activity this year but need to confirm our findings by conducting observations for one or two more seasons. According to this year’s sampling, the first larvae were noticed about a week after adult peak (mid-June), larvae started feeding outside by the end of June, and first damage was noticed in early July. Similarly, during the dry season of 2020, the first observable damage occurred in early July. In August, mostly pupae were found, and in the middle of August we found newly emerged adults. These adults will not produce any more offspring, rather they prepare for overwintering and start finding proper overwintering sites. Several years in a row, we observed that the peak of migration to overwintering sites occurs in early September. During this migration, billbug adults can be found walking on nearby pavement or grass areas. From a management perspective, it is too late to manage this species during their migration. Most of the damage is done and additional damage is not likely; adults are hard to control, especially when they try to hide for the winter. If adults are noticed at this time, the best action is to create a management plan for next season.

Implications for management of billbugs in Massachusetts

Billbugs are stem borers and they are very selective when it comes to host plants. We observed very noticeable differences in the suitability of different cultivars as hosts for billbugs. The understanding of the mechanisms of host plant resistance is the goal of our future research, as it will help develop management recommendations and provide ideas to turfgrass breeders. Selecting resistant cultivars or cultivars with high levels of endophytes are the most environmentally friendly and effective ways to manage billbugs. Another effective, non-chemical approach of billbug management is the use of entomopathogenic nematodes. Several previous studies have demonstrated that entomopathogenic nematodes are effective management tools against adults and larvae (Steinernema carpocapsae), and against larvae (Heterorhabditis bacteriophora).

As for chemical control, according to our preliminary data, the optimal strategy is to target the small larvae which feed inside the stem. Because younger larvae are protected by the plant tissue, the systemic or translaminar active ingredients (chemicals that can be absorbed by the plant) are the only effective option. According to our research, these insecticides are effective if applied at oviposition (at the peak of adult activity or slightly after) or later in the season when larvae are feeding, but at the later time efficacy is slightly lower.

Other options for billbug chemical control are to target adults (the least effective option), and “clean-up” applications when the first signs of damage are observed. Both approaches are less effective but can be necessary if the densities are high. Table 1 summarizes our research and observations on billbug activity, growing degree accumulation, and recommended management strategies.

Table 1. Phenology of billbug complex and management strategies in Western Massachusetts (2023)

| Billbug stage | Calendar Date | GDD accumulation | Management action | Insecticide AIs |

| Adult activity* starts | ~May 5-10 | 200 | Adult monitoring | |

| Peak of adult activity | ~May 25 -31 | 300-400 | Adulticide (contact, fast acting insecticide) application | Pyrethroids: Bifenthrin, Lambda-cyhalothrin, Others Combination products: pyrethroids+neonicotinoids, Clothianidin+bifenthrin IGR: novaluron |

| End of adult activity | ~June 15 | 600 | ||

| First larvae** feeding inside of the stem | ~June 7 | 450 | Larvicide targeting larvae feeding inside of grass plants (systemic or translaminar insecticides) | Neonicotinoids: clothianidin Anthranilic diamides: cyantraniliprole |

| Larvae start feeding outside of the stem | End of June | 650-700 | Larvicide targeting larvae outside of grass plants | Neonicotinoids: clothianidin |

| Large larvae feeding outside of the stem, first pupae, damage becomes apparent | First week of July | 800-900 | Larvicide targeting larvae outside of grass plants | Organophosphates: trichlorfon Neonicotinoids: clothianidin |

| Pupation | August | >1000 | Too late for application | |

| New adults migrate to overwintering sites | September | |||

| * Based on three-year data **Prediction of larval activity is based on one year (2023) preliminary data and empirical observations 2020-2023 |

||||

CAUTION: All pesticides referenced above have been registered and approved for indicated uses according to the best available information at the time of preparation. However, local, state, and federal laws and regulations pertaining to pesticides are subject to change. Pesticide applicators are advised to stay current with laws and regulations governing pesticides and their use. It is unlawful to use any pesticide in any manner other than the registered use. It is the responsibility of the applicator to verify the registration status of any pesticide for the intended use before applying it. Some pesticides referred to above may be classified “for restricted use only” in accordance with federal and/or state regulations. Persons using “restricted use” pesticides must be licensed and certified applicators. When using pesticides, users are further cautioned to read and strictly follow all directions on the pesticide label. The pesticide label is the law. If pesticide label information is in conflict with information contained on this web site, the label shall take precedence.

Olga Kostromytska, Stockbridge School of Agriculture, University of Massachusetts Amherst

Upcoming Events

For details and registration options for these upcoming events, go to the UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, and Urban Forestry Program Upcoming Events Page.

- Invasive Insect Certification Program, Sept. 27, 28, Oct. 10, 11, 25, 26, live via GoToWebinar, 9:30 - 12:30 pm. This six-day webinar series looks at the characteristics of invasive insects, the impacts and costs they have regionally and nationwide, and highlights the biology, ecology, and identification of some of the most destructive insects. Participants may receive a certificate in INVASIVE INSECT MANAGEMENT upon the successful completion of all six webinars; webinars may also be taken individually. Pre-registration required. 2 pesticide contact hours for categories 29, 35, 36, 48, and Applicator's (Core) License for each webinar; 1 MCLP, 1 MCA, 1 MCH credits available; ISA, SAF, and CFE requested.

Pesticide Exam Preparation and Recertification Courses

These workshops are held virtually. Contact Natalia Clifton at nclifton@umass.edu or go to https://www.umass.edu/pested for more info.

Additional Resources

For detailed reports on growing conditions and pest activity – Check out the Landscape Message

For professional turf managers - Check out our Turf Management Updates

For commercial growers of greenhouse crops and flowers - Check out the New England Greenhouse Update website

For home gardeners and garden retailers - Check out our home lawn and garden resources

TickTalk webinars - To view recordings of past webinars in this series, go to: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/ticktalk-with-tickreport-webinars

Diagnostic Services

Landscape and Turf Problem Diagnostics - The UMass Plant Diagnostic Lab is accepting plant disease, insect pest and invasive plant/weed samples. By mail is preferred, but clients who would like to hand-deliver samples may do so by leaving them in the bin marked "Diagnostic Lab Samples" near the back door of French Hall. The lab serves commercial landscape contractors, turf managers, arborists, nurseries and other green industry professionals. It provides woody plant and turf disease analysis, woody plant and turf insect identification, turfgrass identification, weed identification, and offers a report of pest management strategies that are research based, economically sound and environmentally appropriate for the situation. Accurate diagnosis for a turf or landscape problem can often eliminate or reduce the need for pesticide use. See our website for instructions on sample submission and for a sample submission form at http://ag.umass.edu/diagnostics.

Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing - The lab is accepting orders for Routine Soil Analysis (including optional Organic Matter, Soluble Salts, and Nitrate testing), Particle Size Analysis, Pre-Sidedress Nitrate (PSNT), Total Sorbed Metals, and Soilless Media (no other types of soil analyses available at this time). Testing services are available to all. The lab provides test results and recommendations that lead to the wise and economical use of soils and soil amendments. For updates and order forms, visit the UMass Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory web site.

Tick Testing - The UMass Center for Agriculture, Food, and the Environment provides a list of potential tick identification and testing options at: https://ag.umass.edu/resources/tick-testing-resources.