To print this issue, either press CTRL/CMD + P or right click on the page and choose Print from the pop-up menu.

Crop Conditions

Moderate rain fell across the state on Sunday with most areas getting around a quarter of an inch, with some higher amounts in northern Berkshire County. Enough to help water in seeds and new transplants and cool crops down but not enough to get in the way of a great start to pick-your-own season. I know we’re focused on vegetables here but it’s hard not to notice the amazing crop of strawberries we’re seeing out there. Farm stands are full! We’re still seeing asparagus in the Pioneer Valley along with other spring favorites like radishes and hakurei turnips, lettuces and baby bok choy, scallions, and now summer squash and zucchini, along with greenhouse tomatoes. Garlic scapes are being harvested too, which reminds me of the incredible flatbread provided by the farm last night at the Tangerini Farm twilight meeting—garlic scape pesto with goat cheese and strawberries!

Moderate rain fell across the state on Sunday with most areas getting around a quarter of an inch, with some higher amounts in northern Berkshire County. Enough to help water in seeds and new transplants and cool crops down but not enough to get in the way of a great start to pick-your-own season. I know we’re focused on vegetables here but it’s hard not to notice the amazing crop of strawberries we’re seeing out there. Farm stands are full! We’re still seeing asparagus in the Pioneer Valley along with other spring favorites like radishes and hakurei turnips, lettuces and baby bok choy, scallions, and now summer squash and zucchini, along with greenhouse tomatoes. Garlic scapes are being harvested too, which reminds me of the incredible flatbread provided by the farm last night at the Tangerini Farm twilight meeting—garlic scape pesto with goat cheese and strawberries!

Many thanks to Steve and Linda Chiarizio from Tangerini’s for sharing their farm and to Susan Murray from SEMAP for supporting the event and looking after the kids in attendance! We had a great turnout and learned about the subsurface drainage system the farm had installed along with a denitrifying bioreactor. The bioreactor works by diverting the flow of water from the buried tiles through a deep bed of cedar woodchips. The woodchips feed microbes, which promote denitrification to reduce nitrogen pollution in the water. To ensure the longevity of the bioreactor, or reduce the potential for nitrogen loss in non-tiled fields, it’s wise to not overapply nitrogen. A helpful tool that we also talked about at the meeting last night is the pre-sidedress soil nitrate test (PSNT), which is offered by the UMass Soil Testing Lab. The test is just $15 per sample (find the submission form and instructions HERE) and provides a quick snapshot of the plant-available nitrogen in the soil. It should be taken just before the sidedress stage for vegetables to determine if an application of nitrogen is actually necessary. Find more information about interpreting test results and determining the appropriate timing and sidedressing amounts for different crops in the Nitrogen Management section of the New England Vegetable Management Guide.

Our line-up of educational programs continues next week with a twilight meeting at Brookfield Farm in Amherst on June 25—if you plan to come, please register in advance. You can find more details and the registration link HERE. Hope to see you there! And check out the end of this issue for a full list of this season’s events.

Vegetable Pest Alerts

Alliums

Garlic anthracnose was diagnosed on garlic scapes this week. In garlic, this pathogen (Colletotrichum fioriniae) only infects the scapes and bulbils. C. fioriniae has a broad host range, though, including celery, tomato, pear, apple, blueberry, strawberry, and many weeds. On garlic scapes, lesions are sunken and initially tan, turning orange as the fungus produces spores. The spores are dispersed by splashing water. The fungus can survive on crop debris in the soil for several years. Remove scapes and practice good crop rotations.

Garlic anthracnose was diagnosed on garlic scapes this week. In garlic, this pathogen (Colletotrichum fioriniae) only infects the scapes and bulbils. C. fioriniae has a broad host range, though, including celery, tomato, pear, apple, blueberry, strawberry, and many weeds. On garlic scapes, lesions are sunken and initially tan, turning orange as the fungus produces spores. The spores are dispersed by splashing water. The fungus can survive on crop debris in the soil for several years. Remove scapes and practice good crop rotations.

Aphids: We have gotten two reports of small black aphids on onions and scallions this spring. We are working on identifying these aphids, so if you’ve seen something similar on your farm, please let us know (umassveg@umass.edu or 413-577-3976).

Brassicas

Swede midge is currently being caught in pheromone traps in northeast NY now. Swede midge adults are tiny flies that lay eggs in the growing points of brassica crops. The larvae are almost-microscopic, transluscent-to-yellow maggots that feed in the growing point. The feeding damage causes deformation of plants including brown corky tissue, galls, blind-heads, multi-heads, and twisted leaf petioles. We’re not sure about the precise range and incidence of this pest in MA, so if you see this kind of damage on your brassicas, please let us know! Click on the photos to enlarge the view.

Cucurbits

Squash vine borer (SVB) adults were captured in a pheromone trap in Franklin Co. this week (Table 1). SVB is a moth that lays its eggs at the base of thick-stemmed cucurbit crops (e.g. summer squash, zucchini, giant pumpkins, some winter squash, as opposed to thin-stemmed crops like cucumber, watermelon or butternut squash, which are less habitable for the larvae). The larvae tunnel into and up the stem, destroying the plant’s vascular system and causing the plant to wilt and then die. The orange-red and black adults fly during the day and are often mistaken for a bee or wasp because of their color and shape. Pheromone traps are used to monitor adult SVB activity and time pesticide sprays; the threshold for applying a pesticide is 5 moths/week for bush-type cucurbits or 12 moths/week for vining cucurbits. Labeled conventional materials include Assail (neonicotinoid) and several pyrethroids (e.g. Brigade, Asana, Declare, Warrior, Mustang). Entrust and Bacillus thuringensis aizawi have demonstrated efficacy but must be ingested to be effective, making proper spray timing and coverage critical. Note that SVB is not listed on these labels but may be used in states that allow applications to the crop for other target pests. Sprays should be directed at the base of plants. Row cover will also exclude the moths in fields that were not infested last fall. Remove covers during flowering to allow for pollination.

Squash vine borer (SVB) adults were captured in a pheromone trap in Franklin Co. this week (Table 1). SVB is a moth that lays its eggs at the base of thick-stemmed cucurbit crops (e.g. summer squash, zucchini, giant pumpkins, some winter squash, as opposed to thin-stemmed crops like cucumber, watermelon or butternut squash, which are less habitable for the larvae). The larvae tunnel into and up the stem, destroying the plant’s vascular system and causing the plant to wilt and then die. The orange-red and black adults fly during the day and are often mistaken for a bee or wasp because of their color and shape. Pheromone traps are used to monitor adult SVB activity and time pesticide sprays; the threshold for applying a pesticide is 5 moths/week for bush-type cucurbits or 12 moths/week for vining cucurbits. Labeled conventional materials include Assail (neonicotinoid) and several pyrethroids (e.g. Brigade, Asana, Declare, Warrior, Mustang). Entrust and Bacillus thuringensis aizawi have demonstrated efficacy but must be ingested to be effective, making proper spray timing and coverage critical. Note that SVB is not listed on these labels but may be used in states that allow applications to the crop for other target pests. Sprays should be directed at the base of plants. Row cover will also exclude the moths in fields that were not infested last fall. Remove covers during flowering to allow for pollination.

|

Trap Location

|

svb

|

|---|---|

|

Whately

|

5

|

|

Sharon

|

0

|

|

Spray thresholds: 5 moths/night for bush-type cucurbits, or 12 moths/night for vining cucurbits.

|

|

Nightshades

Colorado potato beetle eggs are now hatching and larvae have begun feeding on foliage. Insecticides are most effective if they target small larvae. Do not use the same class of pesticides on successive generations in the same year. Labeled conventional products include pyrethroids, neonicotinoids, novaluron (e.g. Rimon), cyromazine (e.g. Trigard), and diamides (e.g. Verimark, Exirel). There is a new RNAi product called Calantha that is not yet registered in MA but may be soon—it is registered in the other New England states. For organic growers, spinosad (e.g. Entrust) is most effective but can only be used 2 times on only 1 generation of CPB per season. Other options for organic growers include azadirachtin products (e.g. Aza-Direct, Azatin O, Neemix) or pyrethrin (e.g. Pyganic), and the bioinsecticide Beauveria bassiana (e.g. Mycotrol O, Botanigard).

Colorado potato beetle eggs are now hatching and larvae have begun feeding on foliage. Insecticides are most effective if they target small larvae. Do not use the same class of pesticides on successive generations in the same year. Labeled conventional products include pyrethroids, neonicotinoids, novaluron (e.g. Rimon), cyromazine (e.g. Trigard), and diamides (e.g. Verimark, Exirel). There is a new RNAi product called Calantha that is not yet registered in MA but may be soon—it is registered in the other New England states. For organic growers, spinosad (e.g. Entrust) is most effective but can only be used 2 times on only 1 generation of CPB per season. Other options for organic growers include azadirachtin products (e.g. Aza-Direct, Azatin O, Neemix) or pyrethrin (e.g. Pyganic), and the bioinsecticide Beauveria bassiana (e.g. Mycotrol O, Botanigard).

Potato virus Y necrotic strain (PVY) was diagnosed on ‘gold rush’ potatoes in Bristol Co. this week. PVY is an aphid-transmitted virus that affects many solanaceous crops, including potato, tobacco, tomato, and pepper. PVY can cause significant yield losses in heavily infected potato fields and also causes reduced storage quality and postharvest tuber death. PVY has been in the US for a long time but has re-emerged in the last few decades as a major threat to potato and tobacco production for several reasons, including the development of new strains of the virus that cause tuber necrosis, widespread planting of varieties that show little or no PVY symptoms leading to undetected reservoirs of the pathogen, and contamination of seed stocks. The necrotic strain (PVYN) causes severe necrosis on tobacco but only mild leaf mottling and necrosis on potato foliage. The most important way to avoid PVY infection is to use certified disease-free tubers. Insecticides are generally not useful for managing PVY, because the virus is transmitted very quickly during aphid leaf probing and feeding, though newer behavior-modifying pesticides may be useful, including Assail, Belay, Admire Pro, Fulfill, Movento, and Platinum. Planting a non-host barrier crop (e.g. rye, sorghum, wheat) around potato fields can help clear the virus from aphid mouthparts as they migrate into your crop. Reducing areas of bare soil around or within the crop will also make it harder for aphids to “see” your crop. Rogue out symptomatic plants if possible. For more information, see our Potato Virus Y: A Re-Emerging Disease of Potato and Tobacco article.

Potato virus Y necrotic strain (PVY) was diagnosed on ‘gold rush’ potatoes in Bristol Co. this week. PVY is an aphid-transmitted virus that affects many solanaceous crops, including potato, tobacco, tomato, and pepper. PVY can cause significant yield losses in heavily infected potato fields and also causes reduced storage quality and postharvest tuber death. PVY has been in the US for a long time but has re-emerged in the last few decades as a major threat to potato and tobacco production for several reasons, including the development of new strains of the virus that cause tuber necrosis, widespread planting of varieties that show little or no PVY symptoms leading to undetected reservoirs of the pathogen, and contamination of seed stocks. The necrotic strain (PVYN) causes severe necrosis on tobacco but only mild leaf mottling and necrosis on potato foliage. The most important way to avoid PVY infection is to use certified disease-free tubers. Insecticides are generally not useful for managing PVY, because the virus is transmitted very quickly during aphid leaf probing and feeding, though newer behavior-modifying pesticides may be useful, including Assail, Belay, Admire Pro, Fulfill, Movento, and Platinum. Planting a non-host barrier crop (e.g. rye, sorghum, wheat) around potato fields can help clear the virus from aphid mouthparts as they migrate into your crop. Reducing areas of bare soil around or within the crop will also make it harder for aphids to “see” your crop. Rogue out symptomatic plants if possible. For more information, see our Potato Virus Y: A Re-Emerging Disease of Potato and Tobacco article.

Sweet corn

European corn borer (ECB): Several more trapping sites are reporting ECB activity this week, with a high of 16 in Franklin Co. (Table 2). We’re nearing peak flight (630 GDDs) in the Pioneer Valley, but egg laying should be happening in all parts of the state by now. If moths are being reported in your area, scout corn for “shot hole” damage on the leaves and/or lodged tassels with sawdust-like frass. The caterpillars will feed in the whorl and emerging tassel and then move down the stalk to re-enter developing ears. If infested plants exceed 15% of a 50-100 plant sample, treatment with an insecticide is recommended.

Corn earworm (CEW) was captured at 5/6 trapping sites this week. These are probably still moths that overwintered here in the Northeast. Moths that are blown northward from the South usually arrive in July. CEW lays eggs in the silks, so corn that is not yet silking is not at risk of infestation. If trap captures exceed 1.4 moths/week, an insecticide application is warranted (see Table 3). CEW populations can vary widely farm-to-farm, even between two sites that are close to each other, so we recommend trapping on your own farm if you struggle with this pest. Other reasons you may not get good control of CEW include: using Bt corn varieties with only the Cry1a or Cry2a proteins (the only Bt gene that will control CEW is Vip3A, e.g. Attribute II and Attribute Plus series); or relying on Warrior, which is cheap but has demonstrated efficacy as low as 45% in recent years due to resistance. Other pyrethrids are more effective, including bifenthrin (e.g. Brigade), beta-cyfluthrin (Baythroid XL), and zeta-cypermethrin (Mustang). Importantly, you could also use effective non-pyrethroids like Coragen (group 28), Radiant (group 5), Rimon (group 15), Intrepid (group 18), or Avaunt (group 22) as part of your spray program to improve control.

| Nearest Weather station |

GDD (Base 50°F) |

Trap Location | ECB NY | ECB IA | FAW | CEW | CEW SPRay interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western MA | |||||||

| North Adams | 628 | n/a | - | - | - | - | - |

| Richmond | 514 | n/a | - | - | - | - | - |

| South Deerfield | 660 | Whately | 16 | 0 | - | - | - |

| Granville | 537 | Southwick | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5 days |

| Central MA | |||||||

| Leominster | 564 | Leominster | - | - | - | - | |

| Lancaster | 7 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 6 days | ||

| Northbridge | 576 | North Grafton | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 5 days |

| Worcester | 577 | Spencer | - | - | - | - | |

| Eastern MA | |||||||

| Bolton | 571 | Bolton | 0 | 0 | - | 3 | 5 days |

| Stow | 570 | Concord | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 6 days |

| Lawrence | 544 | Haverhill | - | - | - | - | - |

| Ipswich | 531 | Ipswich | - | - | - | - | - |

| - | ND | Millis | - | - | - | - | - |

| East Bridgewater | 547 | North Easton | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sharon | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | ||

| Providence, RI | 558 | Seekonk | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | no spray |

| Swansea | 1 | 0 | - | - | - | ||

|

ND - no GDD data for this location - no numbers reported for this trap n/a - this site does not trap for this pest |

|||||||

| Moths/Night | Moths/Week | Spray Interval |

|---|---|---|

| 0 - 0.2 | 0 - 1.4 | no spray |

| 0.2 - 0.5 | 1.4 - 3.5 | 6 days |

| 0.5 - 1 | 3.5 - 7 | 5 days |

| 1 - 13 | 7 - 91 | 4 days |

| Over 13 | Over 91 | 3 days |

Cut Flower Pest Alerts

Sunflower

Downy mildew was detected in sunflowers in Hampshire Co. Downy mildew in sunflower is caused by Plasmopara halstedii, an obligate parasite that infests certain species of ornamental plants. It survives in the soil for up to 10 years. It can cause systemic or secondary infections. Systemic infections occurs when young seedlings are infected through their roots; this type of infection is favored by cool, wet soils and often kills the plants. If infected seedlings survive, leaves become thick and yellow, with white/gray/purplish growth on leaf undersides (see photos at right). Secondary infections occur when spores from infected leaves are blown by wind or rain to healthy leaves. High humidity, prolonged leaf wetness and cool weather favor the development of downy mildew diseases. Fungicides are generally not effective except as seed treatments. Instead, remove and destroy affected plants. Minimize leaf wetness: use drip irrigation or irrigate in the morning to permit rapid drying. Improve air circulation and light penetration through plant spacing. Do not grow sunflowers repeatedly in the same area where the disease has occurred.

Downy mildew was detected in sunflowers in Hampshire Co. Downy mildew in sunflower is caused by Plasmopara halstedii, an obligate parasite that infests certain species of ornamental plants. It survives in the soil for up to 10 years. It can cause systemic or secondary infections. Systemic infections occurs when young seedlings are infected through their roots; this type of infection is favored by cool, wet soils and often kills the plants. If infected seedlings survive, leaves become thick and yellow, with white/gray/purplish growth on leaf undersides (see photos at right). Secondary infections occur when spores from infected leaves are blown by wind or rain to healthy leaves. High humidity, prolonged leaf wetness and cool weather favor the development of downy mildew diseases. Fungicides are generally not effective except as seed treatments. Instead, remove and destroy affected plants. Minimize leaf wetness: use drip irrigation or irrigate in the morning to permit rapid drying. Improve air circulation and light penetration through plant spacing. Do not grow sunflowers repeatedly in the same area where the disease has occurred.

--Written by Hannah Whitehead and Angie Madeiras

Contact Us

Contact the UMass Extension Vegetable Program with your farm-related questions, any time of the year. We always do our best to respond to all inquiries.

Vegetable Program: 413-577-3976, umassveg@umass.edu

Staff Directory: https://ag.umass.edu/vegetable/faculty-staff

Home Gardeners: Please contact the UMass GreenInfo Help Line with home gardening and homesteading questions, at greeninfo@umext.umass.edu.

Critical Time for Asparagus Weed Management

As asparagus harvest season is wrapping up, we are also approaching a critical time to think about asparagus weed management. Right after the final harvest, you can implement a clean cut, which means no asparagus will be aboveground. This is a good opportunity to think about weed management without risking harm to the asparagus. Consider taking these actions:

As asparagus harvest season is wrapping up, we are also approaching a critical time to think about asparagus weed management. Right after the final harvest, you can implement a clean cut, which means no asparagus will be aboveground. This is a good opportunity to think about weed management without risking harm to the asparagus. Consider taking these actions:

- A final shallow cultivation (less than 3” deep) to manage any emerged weeds before letting ferns grow.

- Apply a systemic herbicide to help manage some of the more difficult perennial weeds such as bindweed (Calystegia sepium), Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense), or mugwort (Artemesia vulgaris). Systemic herbicides are better at managing perennial weeds since the herbicide is transported into the plant and can reduce root growth. But what can travel to the roots of the weeds also has the opportunity to travel to the roots of asparagus. This unique period after the final clean-cut harvest means that there is less of a chance to damage the asparagus. Consider using a synthetic auxin herbicide such as dicamba (Clarity), 2,4-D (Formula 40), or quinclorac (Quinstar 4L). You can also consider using clopyralid (Clean Slate) or glyphosate (Roundup).

- Apply another pre-emergent herbicide for residual weed control during fern growth. It is generally a good idea to use a different pre-emergent from one you may have used at the beginning of the season, before the spears emerged. Here is a list of pre-emergent herbicide options:

- Clomazone (Command 3ME)

- mesotrione (Callisto)

- napropamide (Devrinol 2-XT)

- diruon (Diuron 4L)

- linuron (Lorox)

- metribuzin (Metribuzin 75)

- pendimethalin (Prowl H2O)

- terbacil (Sinbar WDG)

- norflurazone (Solicam DF)

- trifluralin (Treflan)

Websites consulted:

- https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/watch-the-timing-for-post-harvest-weed-control-in-asparagus

- https://blog-fruit-vegetable-ipm.extension.umn.edu/2020/06/weed-management-options-for-asparagus.html

- https://ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/asparagus/integrated-weed-management/#gsc.tab=0

Garlic Harvest and Post-Harvest Considerations

--Written by Crystal Stewart-Courtens, Eastern NY Commercial Horticulture Program, Cornell Cooperative Extension. Originally published in Cornell Veg Edge, Volume 20 Issue 10, June 5, 2024.

Setting up for success at harvest:

As we move towards garlic harvest, there are a few things that growers can do to set themselves up for success. Careful water management, removing any diseased garlic from the field prior to harvest, and careful timing of the harvest will all contribute to maximizing the size and quality of the crop.

As we move towards garlic harvest, there are a few things that growers can do to set themselves up for success. Careful water management, removing any diseased garlic from the field prior to harvest, and careful timing of the harvest will all contribute to maximizing the size and quality of the crop.

- Cull diseased garlic now: Removing any garlic that is prematurely wilting/yellowing between scaping and harvest will help to ensure that you don’t bring diseased garlic into storage, where it could spread disease throughout the crop. If you don’t recognize a problem that you are seeing, seek help from your local Extension educators to get the issue properly identified, especially if it’s spreading.

- Provide one inch of water per week to the crop: Alliums are essentially delicious water balloons and need adequate moisture to reach full size. If on plasticulture plan to irrigate to deliver this amount of water weekly, and if on bare or mulched ground, plan to supplement with irrigation if rainfall isn’t adequate. Stop watering at least one week before harvest to facilitate digging.

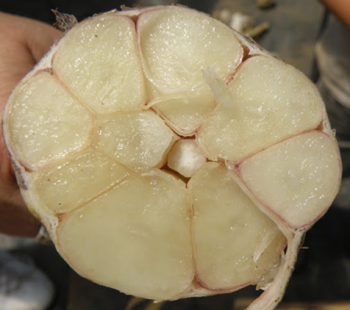

- Harvest at peak maturity: Allowing garlic to reach peak size creates a better seal between the clove wrappers and the clove and between the outer wrapper leaves and the bulb. That seal is part of what determines a bulb’s longevity. Waiting until the tips of the cloves have started to pull away from the scape (hardneck), the cloves are bumpy rather than forming a smooth circle on the bulb, and a small gap forms between the cloves and the scape on the interior of the head are all signals that the garlic has reached peak size (see pictures).

Post-Harvest Handling Best Practices:

There are a number of steps growers can take to help garlic dry quickly, which is the best way to reduce post-harvest disease issues. Topping the garlic, curing it in a warm, dry environment with good air flow, and then moving it to a cool, dry environment will help avoid issues ranging from black mold to eriophyid mites.

- Topping garlic: We have conducted numerous studies on topping garlic prior to harvest and consistently find that it speeds drying and may also decrease the total mass loss over time. The height of the initial cut may range depending on your cutting tool, with anything longer than 1.5 inches working well.

- Cure warm and dry: Similarly, curing at between 85 and 110°F with low relative humidity consistently produces garlic with reduced disease issues. Curing at the high end of this range at the end of the process may also help to kill eriophyid mites which can infest the garlic bulb. Growers can achieve these temperatures passively in high tunnels with shade cloth and fans running directed at the garlic.

- Store cool and dry: When the garlic is dry, all wrapper leaves to the scape will feel dry to the touch. At this point you should move the crop out of the warm curing environment and into a cooler space. Any temperature below 75°F and 75% RH will avoid most surface molds, though temperatures much cooler, down to 40°, will also slow eriophyid mite development if that is a concern.

Preventing Heat Stress in Agriculture

--Written by Kate Brown, Stephen Komar, Michelle Infante-Casella, and William Bamka, Rutgers Cooperative Extension. Originally published in Rutgers Plant & Pest Advisory.

Heat exposure can be a serious concern for agricultural laborers when working outside during the growing season. When a person's ability to adapt to heat stress is exceeded, exposure can lead to reduced productivity, mistakes in job performance, increased workplace incidents, and/or heat-related illnesses. Each person's heat tolerance varies and several factors including type of physical activity, fitness level, underlying health issues, and humidity can dramatically impact the potential for heat related injury. To determine the level of heat risk, employers should consider the job, the environment, and the worker. This fact sheet provides basic knowledge about heat stress, first-aid treatment, and preventative measures that are important to both employers and workers.

Heat exposure can be a serious concern for agricultural laborers when working outside during the growing season. When a person's ability to adapt to heat stress is exceeded, exposure can lead to reduced productivity, mistakes in job performance, increased workplace incidents, and/or heat-related illnesses. Each person's heat tolerance varies and several factors including type of physical activity, fitness level, underlying health issues, and humidity can dramatically impact the potential for heat related injury. To determine the level of heat risk, employers should consider the job, the environment, and the worker. This fact sheet provides basic knowledge about heat stress, first-aid treatment, and preventative measures that are important to both employers and workers.

How the Body Responds to Heat

Sweat is the body's primary method to cool itself and maintain temperature in a narrow range between 97–99°F. Under certain conditions, sweating is insufficient to cool the body, and temperature regulation can be overwhelmed causing a rapid increase in body temperature. Heat stroke, for example, is a life-threatening condition that occurs when the body is unable to cool itself. The result may be a body temperature of 106°F or higher in a matter of only 10–15 minutes. Maintaining a safe body temperature is crucial to the well-being of those working outside. A balance must be struck between heat produced by a body at work and heat lost to or gained from the environment. The initial body response to heat is sweating and circulating blood closer to the skin surface to lower the main body temperature.

When extended heat exposure occurs, a physiological adaptation process called acclimatization occurs in response to increased temperatures. Acclimatization to heat may take weeks, although significant adaptation occurs within a few days of initial exposure. Once acclimatization is achieved, working in the heat results in increased production of a more dilute sweat (lower salt content) and less of an increase in heart rate and body temperature. The body's ability to respond to heat stress decreases with age, obesity, and other health-related factors. Older workers and obese workers are more vulnerable to heat-related illnesses and less capable of working safely in the heat. Pregnancy increases a woman's metabolic demands and may increase sensitivity to heat and humidity.

Other factors that may increase the risk of heat stress include sleep distress, poor physical condition, lack of acclimatization, dehydration, and drug and alcohol use. Many commonly used over the counter and prescription drugs may also interfere with the body's response to heat stress. Preexisting medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, certain skin disorders, and some diseases of the central and peripheral nervous systems, can impair people's normal physiological response to heat stress. Workers should consult their physician for more information concerning the above conditions.

Strategies For Worker Heat Acclimatization

To protect employees from heat-related illness, the following is recommended:

- Schedule new workers for shorter time periods in the heat, separated with frequent break periods.

- Train new workers about heat exposure, symptoms of heat-related illness, and the importance of rest and hydrating with water even during non-work hours.

- Monitor new workers closely for any symptoms of heat-related illness.

- Use a system where new workers do not work alone.

- If new workers talk about heat stress or show any symptoms, allow them to stop working. Administer first aid. Never leave someone alone who is experiencing heat stress symptoms.

- These increased precautions should last for 1–2 weeks. After that time, new workers should be acclimatized to the heat and can safely work a normal schedule.

Methods of Heat Gain or Loss

Major physical processes by which the body gains or loses heat in a hot environment include:

- heat production by normal body functioning (metabolism)

- heat loss by evaporation

- heat loss or gain by convection and radiation (metabolic heat gain is a by-product of both resting and physical exertion)

Evaporation is the cooling (heat loss) of the body that occurs when sweat evaporates from the skin's surface. The rate of this evaporative cooling is usually greatly increased by air movement across the skin with windy conditions outdoors or using fans. During strenuous activities in very hot environments, sweat production may equal one quart per hour; this amount of fluid loss by the body is usually sufficient to prevent overheating. Problems arise in warm humid environments, because humidity and still air interfere with the body's ability to dissipate heat. Sweat that cannot be evaporated from the body, but drips from the skin, will not result in body heat loss.

Convective heat loss or gain is the transfer of heat between the skin and surrounding air. When air temperature is higher than skin temperature, the body gains heat through convection. If air temperature is lower than skin temperature, the body loses heat. The rate of heat gain or loss depends upon the difference between air and skin temperatures and the presence of air movement (wind velocity). The use of fans to continually move cool air next to the skin and move away the air already warmed by the skin is a common method of body cooling.

Radiation is the direct transfer of heat from a hot object (e.g. the sun, hot equipment, a furnace, or a warm wall) to another cooler object, such as a human body, without heating the air in between. The greater the temperature of an object, the more radiation it emits and the warmer the person will feel.

Heat-Related Illnesses

Heat Stress:

Heat stress occurs when the body builds up more heat than it can handle. High temperatures, high humidity, sunlight, and heavy exertion increase the likelihood of heat stress. Excessive heat can reduce concentration, increase fatigue or irritability, and increase the risk of workplace incidents.

Heat Rash

Heat rash is an early warning sign of heat stress. It is commonly associated with hot, humid conditions in which skin and clothing remain damp from unevaporated sweat. Heat rash may involve small areas of the skin or the entire torso. If large areas of skin are involved, sweat production is compromised, resulting in a decreased capacity to work in the heat. Even after the affected area of skin is healed, sweat production will not return to normal in those areas for as long as 4 to 6 weeks.

Preventive measures are aimed at reducing daily exposure to hot and humid conditions. If heat rash occurs, precautions must be taken to avoid skin infections. Treatments include properly cleaning the affected area and applying antimicrobial ointments to prevent infection. Keeping the skin clean and dry for at least 12 hours each day will help prevent severe heat rash.

Heat Syncope

Heat syncope is characterized by dizziness or fainting while standing still in the heat for an extended period. The condition results from blood pooling in the skin and lower body parts which decreases blood flow to the brain. The most serious aspect of heat syncope is it may cause injury or fall incidents. This is especially dangerous while operating machinery. Treatment consists of resting in a cooler environment. Prevention is based on acclimatization and avoiding long periods of immobility while at work.

Heat Cramps

Symptoms include painful cramps or spasms in the legs, arms, or abdomen. The person will probably sweat heavily. Spasms may occur during work or after work has ended and even when at rest. Heat cramps are often caused by a temporary fluid and salt imbalance during hard physical work in hot environments.

First-aid treatments for heat cramps include:

- Applying firm pressure or gently massaging the affected muscle

- Resting in the shade or a cool place

- Drinking small sips of clear juice, such as apple juice or sports drinks that contain electrolytes. Alternatively, salt water can be an option for heat related muscle cramping (one teaspoon of salt per quart of cool water; plain water should be used for those with heart or blood pressure problems).

Heat Exhaustion

Heat exhaustion results from the reduction of body water content or blood volume. The condition occurs when the amount of water lost as sweat exceeds the volume of water intake during heat exposure. Heat exhaustion usually develops after several days of exposure to high temperatures. A person with heat exhaustion may have some or all these signs or symptoms: heavy sweating; clammy, flushed, or pale skin; weakness; dizziness; nausea; rapid and shallow breathing; headache; vomiting; or fainting.

First-aid treatments for heat exhaustion include:

- Move the individual to a cool area.

- Place the person on their backs with their feet raised above the heart.

- Loosen clothing and apply cool, moist cloths to the body, and fan them to dissipate heat.

- Slowly administer sips of clear juice, such as apple juice or sports drinks that contain electrolytes or salt water (plain water for those with heart or blood pressure problems).

- Call a doctor, especially if the person faints or vomits.

Heat Stroke

Heat stroke is a medical emergency and may be life-threatening. The body may either lose its ability to regulate temperature, due to a failure of the central nervous system to regulate sweat control, or its normal heat-regulating mechanism may simply be overwhelmed. Heat stroke can result in coma or death.

Early signs and symptoms of heat stroke include:

- A high body temperature, 104°F or over

- Hot, dry skin that appears bluish or red

- Absence of sweat in 50-75% of victims

- Rapid heart rate

- Dizziness, shivering, nausea, irritability, and severe headache progressing to mental confusion, convulsions, and unconsciousness.

A worker who becomes irrational, confused, or collapses on the job should be considered a heat stroke victim, and you should call 911 immediately. Early recognition of symptoms and prompt emergency treatment is key to aiding someone with heat stroke.

While awaiting the ambulance, begin efforts to cool the victim down by performing the following OSHA recommended first aid for heat related illnesses:

- Place worker in shady, cool area

- Loosen clothing, remove outer clothing

- Fan air on worker; cold packs in armpits

- Wet worker with cool water; apply ice packs, cool compresses, or ice if available

- Provide fluids (preferably water) as soon as possible

- Stay with worker until help arrives

Preventing Heat Stress

Evaluate the Risk of Heat Stress

Monitoring the environmental conditions during work times to make management decisions for workers is an important part of preventing heat-related illnesses. Temperature is not the only factor in implementing heat stress management. Humidity is another important consideration. The heat index is a measure of how hot it feels when the relative humidity is factored in with the actual air temperature.

An environmental heat assessment should account for the following factors: air temperature, humidity, radiant heat from sunlight or other artificial heat sources, and air movement. OSHA recommends the use of wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) monitor to measure workplace environmental heat. OSHA provides this link to calculate the WBGT for a specific location. There is also a NIOSH/OSHA Heat App for Android and iPhone devices that uses the Heat Index as a screening tool.

Management Suggestions for Enhancing Heat Tolerance

- Acclimatization (to heat) is a process of adaptation that involves a stepwise adjustment to heat over a week or sometimes longer. An acceptable schedule for achieving acclimatization is to limit occupational heat exposure to ⅓ of the workday during the first and second days, ½ of the workday during the third and fourth days, and ⅔ of the workday during the fifth and sixth days. The acclimatization procedure should be repeated if a person misses workdays after days off due to illness, vacation, or other reasons for missing one week or more of job duties.

-

Fluid replacement. Provide adequate drinking water for all employees. Recommend to employees they drink plenty of water before work shifts, during work, and after work. Simply relying on feeling thirsty will not ensure adequate hydration. To replace the four to eight quarts of sweat that may be produced in hot environments, people require ½ to one cup of water every 20 minutes of the workday. Potable drinking water kept at a temperature of 59°F or less is recommended.

- Physical fitness is extremely important. The rate of acclimatization is a function of the individual's physical fitness. The unfit worker takes 50% longer to acclimate than one who is fit.

Increasing Safe Work Practices

To find management and guidance tools for determining whether to implement heat stress management plans refer to the CDC documents on Heat Stress and Work/Rest Schedules.

The following list of management options should be considered to prevent heat stress for workers:

- Limit exposure time. Schedule as many physical work activities as practical for the coolest part of the day (early morning or late afternoon). Employ additional help or increase mechanical assistance, if possible, to lighten individual workloads.

- Minimize heat exposure by taking advantage of natural or mechanical ventilation (increased air velocities up to 5 mph increase the rate of evaporation and thus the rate of heat loss from the body) and heat shields/shade when applicable.

- Take rest breaks at frequent, regular intervals, preferably in a cool environment sheltered from direct sunlight. Anyone experiencing extreme heat discomfort should rest immediately and be provided with first aid for heat stress.

- Wear clothing that is permeable to air and loose fitting. Generally, less clothing is desirable in hot environments, except when the air temperature is greater than 95°F or a person is standing next to a radiant heat source. In these cases, covering exposed skin can reduce the risk of heat stress.

- A buddy system may also be helpful. It depends on a fellow worker's ability to spot the early signs of heat stress, such as irritability, confusion, or clumsiness. A ready means of cooling should be available in work areas where heat illness might occur.

Worker Health and Education

-

Periodic medical examinations may help identify those workers who are at greater risk for heat-related illnesses. This is particularly important for those with preexisting health conditions or older workers.

-

Drugs may alter the body's ability to deal with heat stress effectively. Health-care providers can provide important information about possible concerns and make recommendations about safe work practices.

- Alcohol use should be avoided before or while working in a hot environment.

- Worker health and safety education. All agricultural workers exposed to hot environments should receive basic instruction on the causes, recognition, and prevention of the various heat illnesses. Displaying educational posters in multiple languages throughout communal areas can help reinforce training.

References

- Body Temperature Norms. Medline Plus, National Library of Medicine.

- Heat Hazard Recognition. Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

- Heat-Related Illnesses and First Aid. Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

- Heat-Related Illnesses and First Aid. Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

- Protecting New Workers. Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

- Heat Illness Prevention. Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

- Heat Stress: Work/Rest Schedules (PDF). 2017. Center for Disease Control and Prevention and National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Publication No. 2017–127.

This publication is based on the original work of Wei Zhao, Project Director of Agricultural Safety and Health Program, in consultation with Ann L. Kersting, and was initially made possible in part by a grant from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Program on Agricultural Health Promotion Systems for New Jersey.

Events

Field Walk at Brookfield Farm - Amherst, MA

When: Tuesday, June 25, 2024, 4-7pm

Where: Brookfield Farm, 24 Hulst Rd., Amherst, MA 01002

Registration: Free! Please register in advance, for food ordering purposes. Click here to register.

Join Brookfield Farm, the UMass Extension Vegetable Program and NOFA/Mass for a twilight meeting!

- Kerry and Max Taylor from Brookfield Farm will describe the new well they installed last year that includes a solar pump. The well was installed with support from NRCS.

- Sue Scheufele, UMass Extension Vegetable IPM Specialist, will lead a field walk and pest scouting demonstration.

- Maria Gannett, UMass Extension Weed Specialist, will lead a weed walk and discuss weed ID, organic weed management, and the relationship between weeds and soil health.

Presentations 4-6 pm, followed by a light supper.

1 pesticide recertification credit is available for this program.

This event is supported by the Transition to Organic Partnership Program.

Rice in the Northeast Farm School

When: Thursday & Friday, June 27-28, 2024

Where: Boundbook Farm, 276 Burroughs Farm Rd., Vergennes, VT 05491

Registration: $250, plus tent fees for camping. Click here to register.

The 2-day event is an intensive introduction to farming techniques specific to the northeastern United States. Tent camping at the farm is available, but limited to 25 tents. The Farm School registration fee is $250 and tent fees are additional. Registration is limited to 75 attendees.

- How to Farm Rice: Learn how to start a rice farm with rice varieties and technology adapted to the Northeastern U.S climate, growing conditions, and farming landscape. Learn about field preparation, duck-rice systems, drip-irrigation biomulching, crop varieties, harvesting, processing, and and marketing.

- Camping and Evening Event: On-site, tent camping is available on the farm for two nights. oy the delicious local foods and entertainment on the farm, including live music, a bonfire, and early morning birdwatching,

- Network with Future Rice Farmers: Farmers and agricultural extension educators across the Northeast are improving ways to farm rice ecologically. Now is the time to create a Northeastern rice cooperative. Be part of the founding NE farmers and educators to advance peer-to-peer learning.

Field Walk at Hannan Healthy Foods - Lincoln, MA

When: Wednesday, July 3, 2024, 4-6pm

Where: Hannan Healthy Foods, 270 South Great Rd., Lincoln, MA 01773. Park in the lot by the farm stand, carpool if possible as space is limited and the stand will be open to customers at this time.

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

Join Eastern MA CRAFT, UMass Extension, and NOFA/Mass for a pest walk at Hannan Healthy Foods in Lincoln, MA! We will discuss how to identify and monitor some of the most prolific and problematic pests and diseases ubiquitous to organic production. Scouting and identification are the first steps towards proactive mitigation practices, learn how to see the farm with fresh eyes.

2 pesticide recertification credits are available for this program.

This event is supported by the Transition to Organic Partnership Program.

Field Walk at Astarte Farm - Hadley, MA

When: Tuesday, July 9, 2024, 4-6pm followed by a light meal

Where: Astarte Farm, 123 West St., Hadley, MA 01035

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

Join Astarte Farm, the UMass Extension Vegetable Program and NOFA/Mass for a twilight meeting!

- Ellen and Dan from Astarte Farm will lead a tour of the farm, highlighting pollinator habitat that they've installed. The habitat was installed with funding from NRCS.

- Hannah Whitehead, UMass Extension Educator, will talk about the benefits of pollinator habitat for organic farmers.

- Sarah Berquist, UMass Lecturer and cut flower farmer, will discuss the flowers that she grows at Astarte.

1 pesticide recertification credit is available for this program.

This event is supported by and MDAR Specialty Crop Grant and the Transition to Organic Partnership Program.

Field Walk at Morning Glory Farm - Edgartown MA

When: Wednesday, July 17, 2024, 6-8pm

Where: Morning Glory Farm, Edgartown, MA

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

Join UMass Extension specialists Sue Scheufele and Maria Gannett for a field walk at Morning Glory Farm. We will identify current pest and weed issues in vegetable crops and discuss their management. There will be lots of time for Q&A, discussion, and dinner and refreshments will be provided.

2 pesticide recertification credits are available for this program.

This event is co-sponsored by NOFA/Mass and Martha’s Vineyard Ag Society with support from the Transition to Organic Partnership Program.

Water & Climate Change Twilight Meeting at Bardwell Farm – Hatfield, MA

When: Friday, August 2, 2024, 5-7pm, with dinner and discussion to follow

Where: Bardwell Farm, 49 Main St., Hatfield, MA 01038

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

Join UMass Extension and CISA for a climate-themed twilight meeting at Bardwell Farm in Hatfield, MA!

- Lisa McKeag will share findings from her recent water quality survey of farms around MA and discuss potential risks and impacts of weather and climate change and rising year-round temperatures on agricultural water quality.

- Harrison Bardwell will show off his new automated irrigation system, and discuss irrigation practices and funded projects around the farm.

- Sue Scheufele will discuss increasing pest risks caused by a hotter climate on vegetable pests including an on-farm trial for managing Phytophthora blight in peppers hosted by Bardwell Farm.

1 pesticide recertification credit is available for this program.

This event is co-sponsored by CISA as part of their Adapting your Farm to Climate Change Series.

Save the Date! UMass Research Farm Field Day

When: August 13, 2024, time TBD

Where: UMass Crop & Livestock Research & Education Farm, 89 River Rd., South Deerfield, MA

Registration: Coming soon!

Come learn about all the research being done by students and faculty across CNS and by UMass Extension on a tour of the farm. Topics include pollinator habitat, bee health and disease ecology, novel cover cropping strategies, intercropping to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, genetic basis of flowering traits in agriculture, and vegetable variety trials including heat-resistant lettuce varieties for summer production.

Twilight Meeting: Climate Impacts on Weed Management and Soil Health

When: Tuesday, October 8, 2024, 4-6pm, with a light supper to follow

Where: UMass Crop & Livestock Research & Education Farm, 89 River Rd., South Deerfield, MA, 01373

Registration: Free! Please register in advance so we can order enough food. Click here to register.

How are climate change and hotter temperatures affecting our soils? Often, practices like reducing tillage and cover cropping are recommended to improve soil health, reduce risk of topsoil loss and enhance resilience to drought and flood—practices that can also affect weed management. UMass Extension will discuss general impacts of climate change on soil health and highlight current research on updating recommendations for planting timing and overwintering survival of cover crop species in MA. Maria Gannett, UMass Extension Weeds Specialist, will relate these strategies to how they can impact weed management.

1 pesticide recertification credit is available for this program.

This event is co-sponsored by CISA as part of their Adapting your Farm to Climate Change Series.

New England Vegetable & Fruit Conference - Registration Now Open!

When: Tuesday - Thursday, December 17-19, 2024, 8am-6pm daily

Where: Doubletree Hotel, 700 Elm St., Manchester, NH 03101

Registration: Before November 30, $115/person, or $85 for additional attendees if registering as a group. Students $50. Registration capped at 1,400. Click here to register.

The NEVF Conference includes more than 25 educational sessions over three days, covering major vegetable, berry and tree fruit crops as well as various special topics. A Farmer-to-Farmer meeting after each morning and afternoon session will bring speakers and farmers together for informal, in-depth discussions on certain issues. The extensive trade show has over 120 exhibitors.

Vegetable Notes. Maria Gannett, Genevieve Higgins, Lisa McKeag, Susan Scheufele, Alireza Shokoohi, Hannah Whitehead, co-editors. All photos in this publication are credited to the UMass Extension Vegetable Program unless otherwise noted.

Where trade names or commercial products are used, no company or product endorsement is implied or intended. Always read the label before using any pesticide. The label is the legal document for product use. Disregard any information in this newsletter if it is in conflict with the label.

The University of Massachusetts Extension is an equal opportunity provider and employer, United States Department of Agriculture cooperating. Contact your local Extension office for information on disability accommodations. Contact the State Center Directors Office if you have concerns related to discrimination, 413-545-4800.