UMass Extension's Landscape Message is an educational newsletter intended to inform and guide Massachusetts Green Industry professionals in the management of our collective landscape. Detailed reports from scouts and Extension specialists on growing conditions, pest activity, and cultural practices for the management of woody ornamentals, trees, and turf are regular features. The following issue has been updated to provide timely management information and the latest regional news and environmental data.

To read individual sections of the message, click on the section headings below to expand the content:

Scouting Information by Region

Environmental Data

The following data was collected on or about August 7, 2019. Total accumulated growing degree days (GDD) represent the heating units above a 50° F baseline temperature collected via our instruments for the 2019 calendar year. This information is intended for use as a guide for monitoring the developmental stages of pests in your location and planning management strategies accordingly.

|

MA Region/Location |

GDD |

Soil Temp |

Precipitation |

Time/Date of Readings |

||

|

2-Week Gain |

2019 Total |

Sun |

Shade |

|||

|

CAPE |

307 |

1843 |

74 |

70 |

0.77 |

12:00 PM 8/21 |

|

SOUTHEAST |

318.5 |

1995 |

76.1 |

71.6 |

1.3 |

8:30 AM 8/21 |

|

NORTH SHORE |

312.5 |

1936.5 |

71 |

66 |

3.9 |

9:30 AM 8/22 |

|

EAST |

323 |

2099 |

77 |

73 |

3.2 |

5:00 PM 8/21 |

|

METRO |

311 |

1941.5 |

73 |

68 |

2.99 |

6:00 AM 8/21 |

|

CENTRAL |

288.5 |

2017.5 |

70 |

68 |

1.4 |

4:40 PM 8/21 |

|

PIONEER VALLEY |

288 |

2010.5 |

73 |

70 |

2.03 |

10:30 AM 8/21 |

|

BERKSHIRES |

220 |

1810.5 |

74 |

69 |

2.15 |

10:00 AM 8/21 |

|

AVERAGE |

296 |

1957 |

74 |

69 |

2.22 |

- |

n/a = information not available

For both a map and a list of towns currently under water use restrictions, see: https://www.mass.gov/service-details/outdoor-water-use-restrictions-for-cities-towns-and-golf-courses

To check current drought status, see: https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?MA

Phenology

| Indicator Plants - Stages of Flowering (BEGIN, BEGIN/FULL, FULL, FULL/END, END) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLANT NAME (Botanic/Common) | CAPE | S.E. | N.S. | EAST | METRO W. | CENT. | P.V. | BERK. |

|

Clematis paniculata (sweet autumn Clematis) |

* |

* |

Begin |

* |

* |

* |

Begin |

Begin |

|

Polygonum cuspidatum (Japanese knotweed) |

Begin/Full |

Begin/Full |

Begin/Full |

Begin |

Begin |

Begin/Full |

Full |

Begin |

|

Clethra alnifolia (summersweet Clethra) |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full |

Full/End |

|

Hibiscus syriacus (rose-of-Sharon) |

Full/End |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

|

Buddleia davidii (butterfly bush) |

Full/End |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

|

Hydrangea paniculata (panicle Hydrangea) |

Full/End |

Full |

Full/End |

Full |

Full |

Full/End |

Full |

Full |

| * = no activity to report/information not available | ||||||||

Regional Notes

Cape Cod Region (Barnstable)

General Conditions: The average temperature over the period from August 7 – August 21 was 72˚F with a high of 87˚F on August 19 and a low of 55˚F on August 11. There was a brief stretch of very comfortable air around Aug. 10 and 11 with nights reaching into the 50s. Other than that, temperatures have been normal with highs in the 70s and 80s, nighttime lows in the 60s and high relative humidity. There was only a small amount of precipitation during the period, about three quarters of an inch that fell primarily on Aug 8 with very light precipitation on several other days. Topsoil moisture is short and subsoil moisture is adequate. The days are getting shorter and the morning dew heavier.

Pests/Problems: Numerous calls regarding sticky black surfaces (sooty mold) have come in over last two weeks. Though sooty mold can occur as a result of a variety of piercing sucking insects, currently it is likely a result lecanium scale, which is widespread in the area. The sooty mold can be found on any structure underneath a tree with a high population of scale. More detail is provided in the June issue of HortNotes see Trouble Maker of Month; https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/newsletters/hort-notes/hort-notes-2019-vol-305

Other insects or insect damage seen during the period include the last of the adult Japanese beetles and Asiatic beetles, Hibiscus sawfly larvae on hardy Hibiscus, Euonymus scale on Euonymus, chilli thrips on Hydrangea, spidermites on butterfly bush, and oleander aphids on swamp milkweed. Disease symptoms or signs observed over the period include tar spot on both red maple and Norway maple, leaf blight on river birch, cedar-apple rust, apple scab, and Marssonina leaf spot on crabapple [see Disease section below], powdery mildew on oak, lilac, Monarda, and Phlox, downy mildew on Cleome, tip dieback (Botryosphaeria?) on inkberry, and cercospora leaf spot on Hydrangea. A sample came in of Asian jumping worm, which was interesting; http://ccetompkins.org/resources/jumping-worm-fact-sheet Weeds in bloom include purslane (Portulaca oleracea), crabgrass (Digitaria spp.), carpetweed (Mollugo verticillata), cat’s ear (Hypochaeris radicata), pilewort (Erechtites hieraciifolius), ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia), and spotted spurge (Euphorbia maculata). Keep yourself protected from mosquitoes.

Southeast Region (Dighton)

General Conditions: Summer heat returned after a brief respite. Stressed trees are beginning to thin and show color. Unirrigated lawns are brown. Summer weeds such as crabgrass, yellow sorrel, spotted spurge and yellow nutsedge are flourishing. The following plants are in bloom: rose of Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), trumpet vine (Campsis radicans), sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum), Hydrangea macrophylla, H. quercifolia, black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia spp.), Russian sage (Perovskia atriplicifolia), glossy sumac (Rhus glauca), summer sweet (Clethra alnifolia), early goldenrod (Solidago juncea), Joe-Pye weed (Eutrochium purpureum), ironweed (Vernonia spp.), mimosa (Albizia julibrissin), Franklinia alatamaha, common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia), common reed (Phragmites australis) and mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris).

Pests/Problems: The effects of prolonged heat and drought are quite apparent. Be sure that plantings are receiving sufficient water. Yellow jackets, other hornets and wasp nests are becoming quite apparent and aggressive. I have reports of several workers being badly stung. Be sure to check areas where crews will be working ahead of time. Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE) and West Nile Virus have been found in local mosquitoes. At least two persons have contracted EEE in the region. Aerial spraying operations have begun. Be sure to take appropriate precautions such as avoiding being in areas and at times when mosquitoes are active and using repellents. For more information about EEE and aerial spraying for mosquitoes, visit: State public health officials announce second human case of EEE in the Commonwealth: https://www.mass.gov/news/state-public-health-officials-announce-second-human-case-of-eee-in-the-commonwealth

Eastern Equine Encephalitis: https://www.mass.gov/service-details/eee-eastern-equine-encephalitis

Summer 2019 Aerial Mosquito Control: https://www.mass.gov/guides/aerial-mosquito-control-summer-2019

North Shore (Beverly)

General Conditions: This past two-week reporting period was generally hot and humid. Day temperatures were in the mid-80s most days with a few days in the mid to high 70s. Temperatures above 90˚F were recorded on one day during this reporting period. Night temperatures were in the low- to mid-60s on most nights with only two nights in the low 70s. Scattered thunderstorms were reported in the region for several days, bringing a significant amount of rainfall. In one of the towns in the region, a storm brought down trees. Due to moist soil, turf on lawns is green and fresh. There has been no need for watering garden plants and irrigating lawns in most areas in the region. Woody plants seen in bloom include: panicle Hydrangea (Hydrangea paniculata), butterfly bush (Buddleia davidii), rose-of-Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus), and summer sweet Clethra (Clethra alnifolia). Herbaceous plants seen in bloom include: garden phlox (Phlox paniculata), Hostas (Hosta spp.), Sedums (Sedum spp.), Clematis vines (Clematis paniculata), black eyed Susan(Rudbeckia hirta), coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), milkweed (Asclepias spp.), water lily (Nymphaea odorata) and an assortment of summer annual plants.

Pests/Problems: Magnolia scale was observed on saucer Magnolia (Magnolia soulangeana). If magnolia scale is limited to a few branches, it’s possible to prune out infested twigs. Otherwise, use registered pesticides labelled for use on Magnolia scale. Multiple treatments may be needed to fully eliminate heavy infestations. Powdery mildew was observed on lilac, bee balm (Monarda didyma) and Rudbeckia. Brown ambrosia aphid (Uroleucon ambrosiae) infestations continue to be observed on Mexican sunflower (Tithonia spp.). Weeds continue to thrive in landscapes. Some of the weeds observed in bloom include: white clover (Trifolium repens), yellow wood sorrel (Oxalis stricta), purslane (Portulaca oleracea), prostrate spurge (Euphorbia maculata), bittersweet nightshade (Solanum dulcamara), Japanese knotweed (Polygonum cuspidatum), pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus), ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia) and goldenrod (Solidago spp). Ticks and mosquitoes continue to be very active. Always protect yourself with repellent when working or walking outdoors in the woods.

East Region (Boston)

General Conditions: Over the past two weeks we have experienced a typical variety of August weather. High temperatures averaged 83˚F, ranging from 75˚F to 92˚F. Low temperatures averaged 64˚F, ranging from 54˚F to 71˚F. We received 3.2 inches of rain over this period with 3.12 inches falling in one storm over the evening of August 7th and 8th. We are currently at 2099 GDDs having gained 323 GDDs in the two-week period. Hibiscus spp. and Hydrangea spp. in their wide variety of forms and colors are dominating the residential landscape. Herbaceous perennials continue to add color - several in bloom include: Eutrochium purpureum (Joe Pye weed), Helianthus tuberosus (Jerusalem artichoke), Kirengeshoma palmata (yellow wax bells) and Perovskia atriplicifolia (Russian sage). Pollinators are busy foraging in the gardens.

Pests/Problems: Soils remain dry despite the 3.2 inches of rain we received over the past two weeks. Unirrigated turf is browning out while crabgrass (Digitaria spp.) and yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus) are visibly thriving. Unmanaged pokeweed (Phytolacca americana) continues to gain in size while simultaneously flowering and producing mature fruit. Wild cucumber vine (Sicyos angulatus) is climbing any available plants and flowering. Japanese knotweed (Polygonum cuspidatum) is beginning to flower. Squash vine borer has put an end to many vegetable gardens. Adult Viburnum leaf beetles (Pyrrhalta viburni) have deposited eggs on the twigs of susceptible Viburnum. Common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisifolia) and many grasses are distributing an abundance of pollen.

Metro West (Acton)

General Conditions: Summer is coming to an end. Day length is shorter - currently at 13:39 hours with sunrise at 5:58 a.m. and sunset at 7:38 p.m. - and is getting shorter every day. Plants are heavy with fruit, seed, berries, and nuts and temperatures are cooling off. The historical monthly average rainfall for August is 3.72”. During this past two-week reporting period, 2.99” of rain was recorded. The bulk of it fell in 2 storm events, 1.79” measured on the 7th, and 0.97” on the 17th. In some stage of bloom at this time are the following woody plants: Albizia julibrissin (silk tree), Buddleia spp. (butterfly bush), Clethra alnifolia (summersweet), Hibiscus syriacus (rose-of-Sharon), H. paniculata (panicle Hydrangea) and its many cultivars including 'Tardiva', Potentilla fruiticosa (Potentilla), and Rosa 'Knockout' (knockout family of roses). Woody vines in bloom are: Campsis radicans (trumpet vine) and Clematis spp. (Clematis). Contributing even more color and interest to the landscape are some flowering herbaceous plants including: Astilbe spp. (false Spirea), Boltonia asteroides (Bolton’s aster),Campanula takesimana ‘Elizabeth’ (bellflower), Cichorium intybus (Chicory), Coreopsis spp. (tickseed), C. verticillata (threadleaf Coreopsis), Daucus carota (Queen Anne's lace), Echinacea purpurea (coneflower) and its many cultivars, Eutrochium purpureum (Joe Pye weed), Hemerocallis fulva (orange daylily), H. spp. (daylily), Hosta spp. (plantain lily), Kirengeshoma palmata (yellow wax bells), Leucanthemum spp. (shasta daisy), Lilium spp. (lily), Lythrum salicaria (purple loosestrife), Monarda didyma (scarlet bee-balm), Patrinia gibbosa (Patrinia), Perovskia atriplicifolia (Russian sage), Phlox carolina (Carolina Phlox), P. paniculata (Garden Phlox), Rudbeckia fulgida var. sullivantii 'Goldsturm' (black-eyed Susan), Sedum ‘Rosy Glow’ (stonecrop), Senna marilandica (wild Senna), Solidago spp. (goldenrod), and Tanacetum vulgare (tansy).

Pests/Problems: Despite the recent lack of rain (and as of August 13th) this area and most of the state, with the exception of a small area located in the far south western section of the state, has not been classified in a drought status according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?MA

Central Region (Boylston)

General Conditions: We enjoyed some relatively cooler temperatures for several days during the reporting period, with several days of high temperatures not reaching 80˚F. We touched the high 50’s overnight for excellent sleeping weather. Then the heat and humidity returned to remind us what summer usually feels like. We seem to be in a pattern of scattered thunderstorms in the afternoon/evening hours that bring the promise of rain, but virtually no relief from what has been the first prolonged dry spell of the summer. Despite the unsettled air and high heat and humidity, there is plenty in bloom at the moment. Native asters look fabulous, especially Eurybia divaricata (white wood aster). The Joe-Pye weeds have been going strong for a while. Eutrochium maculatum (spotted Joe-Pye), Eupatorium perfoliatum (boneset), and Ageratina altissima (white snakeroot), all of which at one time shared the genus Eupatorium, and are all now in varying stages of flower. Clethra alnifolia (summersweet) is still going strong and is constantly abuzz with pollinator activity. Spiraea tomentosa (steeplebush), a critical pollen source for native bumblebees, is open now. We’re also seeing an abundance of pollinator activity - a great diversity of butterflies and hordes of bees.

Pests/Problems: Deer activity has noticeably picked up in the garden after a period of virtually no deer browse since April. Deer flies and mosquitoes are in abundant supply. There has been very little tick activity all season. Slugs and snails continue to be observed in large numbers. Ragweed is flowering. Powdery mildew is becoming more prolific, especially on Monarda, lilac, and peony foliage. Dogwood sawfly, blister beetle, cabbage looper, and cross hatched cabbage worm have all been observed damaging respective host plants.

Pioneer Valley Region (Amherst)

General Conditions: We enjoyed some incredible, early autumn-like weather in the Pioneer Valley during stretches of this past reporting period and then summer returned. Mid-August in the Pioneer Valley was feeling more like late September, with high temperatures in the low 80s, beautifully cool nights in the 50s and comfortable dew points. Coupled with the bright sun, it was nearly perfect conditions. Humidity started building on Saturday, 8/17 and then temperatures followed on 8/18, creating another mini heat wave for the Pioneer Valley on 8/18 and 8/19. Monday, 8/19 was the epitome of a scorching New England day in August with air so humid and thick you could see the haze all day. Dew points hovered in the lower 70s and by late afternoon there was already dew on the grass. At the time of writing for the early August installment of the LM, the region was receiving a good dousing of rainfall, with >1.5ʺ of accumulation on 8/7. It was immediately absorbed by the dry soils and turfgrasses. Since that time, rainfall has been frequent but accumulations have been minor at best. Storms moved through the region on 8/13, 8/14, and 8/17–8/19 but collectively amounted to less than 0.5ʺ. Another storm with the potential for significant rain was pushing through the region at the time of writing on 8/21. The scattered nature of summer rainstorms is a good reason to purchase a high-quality rain gauge. The two storms on 8/17 and 8/18 were a spectacle, with some major thunder and lightning but not much in the way of rain. Soils remain dry in most locations, save for naturally wet, low-lying pockets of the landscape. The only thing to do is continue with watering and weeding, weeding and watering. Crabgrass is lush and thick at this time and has gone to seed. Despite the dry conditions and recent heat, the majority of trees and shrubs in the landscape seem to be tolerating this summer fairly well. This time of the year, it’s natural for many plants to wear the scars of the season: leaf scorch, branch dieback, foliar spots/blotches, leaf yellowing and some premature leaf shedding. The sun angle is dramatically different now and shade is creeping into once sunny landscapes.

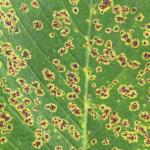

Pests/Problems: Foliar damage from the honeylocust plant bug is abundant and still readily visible (see photo). Infested leaves are often stunted, curled and otherwise deformed with chlorotic flecking. Septoria leaf spot was identified from a paper birch on the UMass campus (see photo). Symptoms appear as angular spots and blotches scattered across the surface of the foliage. Powdery mildews are now common on lilac, bee balm, and oak, among other woody and non-woody plants. Tubakia leaf blotch is developing on oaks with a habit of the disease on the UMass campus (see photos). Symptoms are still mostly in the early to middle stages of development and the dry weather has suppressed activity compared to 2018. Leaf spots are reddish in color and circular in shape. A marginal blight may also be caused by Tubakia. Apple scab or Marssonina leaf blotch, or a combination of the two, may be responsible for defoliation of apple and crabapple at this time. See the Disease section for images of Marssonina on apple. Wood-rotting fungi continue to appear in the landscape so keep an eye out for them. Their tenure may be brief if they’re in the path of the lawnmower. Spider mites, in particular the spruce spider mite, is poised to make a grand return this fall. It appears that the heavy rains during autumn of 2018 might have suppressed populations late last year, as there was reduced activity early in the 2019 growing season. But the drier weather this season and their rapid population buildup seems to have allowed ample recovery. Scout for flecking symptoms on susceptible conifers and treat accordingly as we enter the cooler weather to come in mid- to late-September. Ragweed can be readily found now along roadsides.

Berkshire Region (Great Barrington)

General Conditions: The past two weeks have been a mix of hot, humid, cool, moist, and dry weather. The high temperatures during the reporting period occurred this week as temperatures rose in the high 80s. Otherwise, daily temperatures during the period yo-yoed between the mid- 70s and low 80s. The coolest temperature (49˚F) was registered on the morning of August 11th. Showers were not infrequent but when they occurred, they were brief and never saturated soils. Soils for the most part have moderate to dry levels of moisture. Turfgrass growth has been slower than it was earlier this summer but, except for scalped lawns, lawns look healthy. While turfgrass has been slow, weed growth has progressed at a steady pace and many weeds are now setting seeds. Weed management is a top priority. This is a good time to be sowing green manure cover crops where new flower beds and shrubs borders are to be planted next spring.

Pests/Problems: The foliage of many woody and herbaceous plants have a worn look as leaf spot diseases, leaf scorch, and leaf blights have been common this summer. Powdery mildew is prominent now on ninebark (Physocarpus) and lilacs. Premature defoliation is occurring on crabapples due mostly to apple scab and on many roses infected with black spot. Iron chlorosis is evident on ericaceous species growing in some high pH locations, not unusual for much of Berkshire County where limestone is the prominent bedrock. However, chlorosis is also visible on plants growing adjacent to cement foundations. Colorful fifth stage nymphs of the green stink bug (Chinavia hilaris) were found on the leaves of a linden tree. This insect feeds on a wide variety of trees and herbaceous plants including fruit trees and vegetable plants. Japanese beetles were late to appear this summer. Some locations reported a much lower population than usual while in other areas, the population was about the usual or slightly less in number. Could continuously saturated soils from heavy and frequent rains last year from late summer through fall have affected the survival of beetle grubs? Sooty mold on tulip trees, copper beech, and other trees is not uncommon and is an indicator of sucking type insects, notably aphids. Boxwood leafminer larvae are actively feeding in the leaves of boxwood. Deer ticks, mosquitoes, wasps, slugs and snails remain active. The most interesting wasp observed is the cicada killer wasp (Sphecius speciosus). At nearly 2 inches in length, it is a fierce looking wasp yet is not aggressive. Only the female stings and only when disturbed. Cicada killers build nests in loose textured soils, often near sidewalks or stone paths. The openings to their nests are about ¼ inch in diameter. As the name implies, this wasp kills cicadas and brings them back to their nests to feed the larvae. As vegetation in unmanaged landscapes hardens, browsing on managed landscape and garden plants by rabbits, woodchucks, chipmunks, squirrels, and deer has picked up recently. They especially favor succulent vegetation such as Hostas.

Regional Scouting Credits

- CAPE COD REGION - Russell Norton, Horticulture and Agriculture Educator with Cape Cod Cooperative Extension, reporting from Barnstable.

- SOUTHEAST REGION - Brian McMahon, Arborist, reporting from the Dighton area.

- NORTH SHORE REGION - Geoffrey Njue, Green Industry Specialist, UMass Extension, reporting from the Long Hill Reservation, Beverly.

- EAST REGION - Kit Ganshaw & Sue Pfeiffer, Horticulturists reporting from the Boston area.

- METRO WEST REGION – Julie Coop, Forester, Massachusetts Department of Conservation & Recreation, reporting from Acton.

- CENTRAL REGION - Mark Richardson, Director of Horticulture reporting from Tower Hill Botanic Garden, Boylston.

- PIONEER VALLEY REGION - Nick Brazee, Plant Pathologist, UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab, reporting from UMass Amherst.

- BERKSHIRE REGION - Ron Kujawski, Horticultural Consultant, reporting from Great Barrington.

Woody Ornamentals

Diseases

Recent pests and pathogens of interest seen in the UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab https://ag.umass.edu/services/plant-diagnostics-laboratory:

Marssonina leaf blotch, caused by Marssonina coronaria (also known as Diplocarpon mali) of crabapple (Malus sp.). Old landscape crabapple, possibly over 50-years-old, resides in full sun with well-drained soils. Starting in late spring, premature leaf shedding was observed and has since intensified throughout the season. For unknown reasons, Marssonina has become much more abundant in recent years in both landscapes and orchards, causing concern for growers. When it occurs in conjunction with other foliar disease of Malus, such as apple scab and frogeye leaf spot, significant defoliation occurs. See photos below from an apple on the UMass campus with Marssonina leaf blotch.

Canopy dieback of Green Giant arborvitae (Thuja standishii x plicata) caused by needle and shoot blight from Pestalotiopsis and Phyllosticta along with secondary colonization by cedar bark beetles (Phloeosinus sp.). Trees are 15-years-old and were planted at a residential property in October of 2018. Dieback was first observed in the spring of this year and has progressively developed since that time. Planted at the edge of a property with part shade. The trees likely suffered some combination of transplant shock and winter injury, which predisposed them to the needle and shoot blight infections. Once stressed, the cedar bark beetles invaded, furthering the dieback. This sample illustrates the combination of abiotic and biotic stresses that ultimately lead to visible dieback in trees and shrubs in the landscape.

Willow anthracnose of white willow (Salix alba) caused by Colletotrichum salicis. Tree is approximately 75-years-old and has been present at the site for nearly as long. In early August, the managing arborist noted anthracnose-like symptoms in the canopy, which included blackening and dieback of young shoots, petiole and leaf lesions, wilting and premature leaf shedding. The blackened stem cankers stand out in sharp contrast against the golden color of the stems.

Dieback and death of Dark American arborvitae (Thuja occidentalis ′Nigra′) due to transplant shock. Over 230 trees, approximately five to seven-years-old, were planted at a commercial site in the fall of 2018. Despite the good conditions for transplanting last fall, many suffered winter injury and had to be replaced this spring. The site is full sun, exposed and very windy at times. Replacements were planted in late June of this year and received regular watering after planting but many declined and died. Symptoms included brown and desiccated needles that progressed to outright death. Two trees were submitted for analysis that were representative of the group. The root balls were very small given the size of the trees and there was no new root growth in 2019. The accompanying soils from the source were also poor with no organic matter present. Weak stock coupled with the shock of transplant was likely the primary cause of decline and death.

Needle browning and branch dieback of true fir (Abies sp.) caused by the elongate hemlock scale (Fiorinia externa), Rhizosphaera needle cast and Phomopsis stem cankering. Tree is approximately 20-years-old and resides in a residential lawn with full sun and dry soils. The submitted branch segments showed the tree has a severe infestation of the EHS and while symptoms were not noticed in previous years, they were present had closer inspection been made. Unfortunately, this is common for firs and hemlocks with EHS infestations; infestations are not detected until populations are very high. This spring, new growth was stunted and browned as the season progressed. Rhizosphaera is not a primary issue for true firs when healthy, but when they are stressed it can result in significant needle shedding. True firs are shallow-rooted and the surrounding lawn grass is competing for water and nutrients.

Stem cankering and canopy dieback of inkberry (Ilex glabra) caused by Botryosphaeria, Phomopsis and Fusarium. The shrub was newly purchased and planted this spring. In mid-July, the shoot tips began to die and the foliage became curled and blighted. The site is shaded and soils are wet with drip irrigation provided. All three pathogens are widespread on nursery stock and in the landscape on established plants. The shaded setting was likely a stark departure from the full sun at the nursery and together with the shock of transplant, likely facilitated disease development. Depending on how the plant responds to treatment, removal and replanting may be a better option compared to the long road of recovery.

Black spot anthracnose of American elm (Ulmus americana) caused by Stegophora ulmea. The tree is approximately 100-years-old and is regularly treated with Arbotect for Dutch elm disease. Signs of the pathogen include raised, black-colored spots with orange to yellow margins. The tree had a significant infection with a large number of spots present (see photos below). When severe early in the season, black spot can result in significant defoliation but is often not a major disease of elms. However, when leaves yellow and die as a result of infection, these symptoms can mimic DED and therefore accurate identification is important.

Report by Nick Brazee, Plant Pathologist, UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab, UMass Amherst.

Insects

Acorn Anomaly? – Updates

Premature acorn drop on oaks (Quercus spp.) was previously reported in the Landscape Message released on August 7th. While this can be caused by environmental stress, it is also possible that a tiny gall wasp, possibly Callirhytis operator, is responsible. Galls created by this insect have been referred to as acorn pip galls. Acorns on close examination will show a flattened, tooth-like or wedge-shaped gall between the acorn and its cap. The life cycle of this insect, like many gall-forming insects, is complex. A spring and fall generation has been reported, each causing different types of galls on oak. The fall form, which has now been reported in southeastern NH, CT, RI, and MA, attacks 1-year old acorns which, due to the chemistry of the gall, terminate and fall to the ground. Eventually, the gall, which becomes softened, falls from the acorn, leaving behind a hole. Acorns can be damaged to the extent that they are no longer viable. Like with most gall wasps, not much is known about this insect, and outbreak events are rare. At this time, activity from this insect has been observed in the Berkshire (8/14/19) and Hampshire (8/20/19) Counties of Massachusetts. What impact will this insect have on oak reproduction if the viability of acorns is compromised? We likely do not have to worry. Oaks flood the environment with their acorns, in massive numbers, from time to time (called “mast” years). This helps ensure survival, including guaranteeing a certain percentage of acorns will produce new trees despite insect activity and activity from the other abundant wildlife that enjoy acorn crops.

Premature acorn drop on oaks (Quercus spp.) was previously reported in the Landscape Message released on August 7th. While this can be caused by environmental stress, it is also possible that a tiny gall wasp, possibly Callirhytis operator, is responsible. Galls created by this insect have been referred to as acorn pip galls. Acorns on close examination will show a flattened, tooth-like or wedge-shaped gall between the acorn and its cap. The life cycle of this insect, like many gall-forming insects, is complex. A spring and fall generation has been reported, each causing different types of galls on oak. The fall form, which has now been reported in southeastern NH, CT, RI, and MA, attacks 1-year old acorns which, due to the chemistry of the gall, terminate and fall to the ground. Eventually, the gall, which becomes softened, falls from the acorn, leaving behind a hole. Acorns can be damaged to the extent that they are no longer viable. Like with most gall wasps, not much is known about this insect, and outbreak events are rare. At this time, activity from this insect has been observed in the Berkshire (8/14/19) and Hampshire (8/20/19) Counties of Massachusetts. What impact will this insect have on oak reproduction if the viability of acorns is compromised? We likely do not have to worry. Oaks flood the environment with their acorns, in massive numbers, from time to time (called “mast” years). This helps ensure survival, including guaranteeing a certain percentage of acorns will produce new trees despite insect activity and activity from the other abundant wildlife that enjoy acorn crops.

More information about this insect has been shared by Dr. Gale Ridge of the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station: https://bit.ly/2TQtEJw

Monarchs

Monarch caterpillars (Danaus plexippus plexippus) are for many reasons a “hot topic” for those of us who are entomophiles, but are of particular interest at this time of year in Massachusetts as we may have the special chance to witness “generations 3 and 4” of the annual monarch life cycle. Some describe these generations as the “great” and “great-great grandchildren” of the monarchs who famously overwinter in parts of Mexico. Some generation 3 individuals are capable of migrating and generation 4 individuals migrate south in the fall and return northward in the spring. It takes multiple generations for this species to make its spectacular migration. A great explanation of this can be found here: https://monarchlab.org/biology-and-research/biology-and-natural-history/breeding-life-cycle/annual-life-cycle/

Recently we have received questions pertaining to “what can I do to help or encourage monarchs?” The University of Minnesota’s Monarch Lab states that the most important thing you can do for monarchs in the USA is to help create breeding habitat through the planting of milkweed. They advise visiting the following web page for more information: https://monarchjointventure.org/get-involved/create-habitat-for-monarchs

Woody ornamental (and other) insect and non-insect arthropod pests to consider, a selected few:

- Asian Longhorned Beetle: (Anoplophora glabripennis, ALB) Look for signs of an ALB infestation which include perfectly round exit holes (about the size of a dime), shallow oval or round scars in the bark where a female has chewed an egg site, or sawdust-like frass (excrement) on the ground nearby host trees or caught in between branches. Be advised that other, native insects may create perfectly round exit holes or sawdust-like frass, which can be confused with signs of ALB activity.

The regulated area for Asian longhorned beetle is 110 miles2 encompassing Worcester, Shrewsbury, Boylston, West Boylston, and parts of Holden and Auburn. If you believe you have seen damage caused by this insect, such as exit holes or egg sites, on susceptible host trees like maple, please call the Asian Longhorned Beetle Eradication Program office in Worcester, MA at 508-852-8090 or toll free at 1-866-702-9938.

To report an Asian longhorned beetle find online or compare it to common insect look-alikes, visit: http://massnrc.org/pests/albreport.aspx or https://www.aphis.usda.gov/pests-diseases/alb/report .

- Bagworm: Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis is an occasionally encountered, fascinating Lepidopteran pest. Bagworm caterpillars were collected from young London planetree plantings in Northampton, MA on 7/31/19 by the bucket-full and kindly dropped off at the UMass Plant Diagnostics Laboratory. Activity from this insect has also recently been reported, with photo evidence, from Somerset, MA and Bridgewater, MA. These caterpillars develop into moths as adults. Their behaviors, life history, and appearance are interesting. The larvae (caterpillars) form “bags” or cases over themselves as they feed using assorted bits of plant foliage and debris tied together with silk. As the caterpillars feed and grow in size, so does their “bag”. Young, early instar caterpillars may feed with their bag oriented skyward, skeletonizing host plant leaves. As these caterpillars grow in size, they may dangle downward from their host plant, and if feeding on a deciduous host, they can consume the leaves down to the leaf veins. Pupation can occur in southern New England in late September or into October and this occurs within the “bag”. Typically, this means that the caterpillars could encounter a killing frost and die before mating could occur. However, in warmer areas of Massachusetts or if we experience a prolonged, warm autumn, it is possible for this insect to overwinter and again become a problem the following season. If the larvae survive to pupation, adult male moths emerge and are winged, able to fly to their flightless female mates. The adult male is blackish in color with transparent wings. The female is worm-like; she lacks eyes, wings, functional legs, or mouthparts. The female never gets the chance to leave the bag she constructs as a larva. The male finds her, mates, and the female moth develops eggs inside her abdomen. These eggs (500-1000) overwinter inside the deceased female, inside her bag, and can hatch roughly around mid-June in southern New England. Like other insects with flightless females, the young larvae can disperse by ballooning (spinning a silken thread and catching the wind to blow them onto a new host). While arborvitae and junipers can be some of the most commonly known host plants for this insect, the bagworm has a broad host range including both deciduous and coniferous hosts numbering over 130 different species. Bagworm has been observed on spruce, Canaan fir, honeylocust, oak, European hornbeam, rose, and in this case, London planetree among many others. At this time, we are at the point where chemical management of bagworms may not be effective. This insect can be managed through physical removal, if they can be safely reached. Squeezing them within their bags or gathering them in a bucket full of soapy water (or to crush by some other means) can be effective ways to manage this insect on ornamental plants. Early instar bagworm caterpillars can be managed with Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki (Btk) but this is most effective on young bagworms that are no larger than ¾ inch in length. As bagworms grow in size, they may also have behavioral mechanisms for avoiding chemical management. At this point in the season, physical removal (if possible) may be the best option. This will also preserve any natural enemies that would be found attacking this insect, such as certain parasitic wasps. It is also important to note that the bags from dead bagworms will remain on the host plant, so check the viability of the bagworms by dissecting their bags to avoid unnecessary chemical applications. Historically in Massachusetts, bagworms have been mostly a problem coming in on infested nursery stock. With females laying 500-1000 eggs, if those eggs overwinter the population can grow quite large in a single season on an infested host. Typically, this insect becomes a problem on hedgerows or plantings nearby an infested host plant. Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis is found from Massachusetts to Florida, and is typically a more significant pest in southern climates.

- Deer Tick/Blacklegged Tick: Check out the archived FREE TickTalk with TickReport webinars available here:https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/webinars . The next live webinar will be held on October 9, 2019 with Dr. Stephen Rich of the UMass Laboratory of Medical Zoology. Previous webinars including information about deer ticks and associated diseases, American dog ticks and lone star ticks and associated diseases, ticks and personal protection, and updates from the Laboratory of Medical Zoology are archived at the link above.

Deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) nymphs (immatures) are active at this time, and may be encountered through August. For images of all deer tick life stages, along with an outline of the diseases they carry, visit: http://www.tickencounter.org/tick_identification/deer_tick .

Anyone working in the yard and garden should be aware that there is the potential to encounter deer ticks. The deer tick or blacklegged tick can transmit Lyme disease, human babesiosis, human anaplasmosis, and other diseases. Preventative activities, such as daily tick checks, wearing appropriate clothing, and permethrin treatments for clothing (according to label instructions) can aid in reducing the risk that a tick will become attached to your body. If a tick cannot attach and feed, it will not transmit disease. For more information about personal protective measures, visit: http://www.tickencounter.org/prevention/protect_yourself . For a quick overview of skin repellents available to protect yourself from ticks, visit “Tickology: Skin Repellents” by Larry Dapsis of Cape Cod Cooperative Extension:https://bit.ly/2J8IJBl .

Have you just removed an attached tick from yourself or a loved one with a pair of tweezers? If so, consider sending the tick to the UMass Laboratory of Medical Zoology to be tested for disease causing pathogens. To submit a tick to be tested, visit: https://www.tickreport.com/ and click on the blue “Order a TickReport” button. Results are typically available within 3 business days, or less. By the time you make an appointment with your physician following the tick attachment, you may have the results back from TickReport to bring to your physician to aid in a conversation about risk.

The UMass Laboratory of Medical Zoology does not give medical advice, nor are the results of their tests diagnostic of human disease. Transmission of a pathogen from the tick to you is dependent upon how long the tick had been feeding, and each pathogen has its own transmission time. TickReport is an excellent measure of exposure risk for the tick (or ticks) that you send in to be tested. Feel free to print out and share your TickReport with your healthcare provider.

- Emerald Ash Borer: (Agrilus planipennis, EAB) The Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation has recently confirmed emerald ash borer in Plymouth County, MA for the first time, along with additional communities in counties where this insect has previously been confirmed in the state. The detection in Plymouth County was made with a green funnel trap, where two adult beetles were caught in West Bridgewater, MA. A map of these locations and others previously confirmed across the state may be found here: https://ag.umass.edu/fact-sheets/emerald-ash-borer .

This wood-boring beetle readily attacks ash (Fraxinus spp.) including white, green, and black ash and has also been found developing in white fringe tree (Chionanthus virginicus) and has been reported in cultivated olive (Olea europaea). Signs of an EAB infested tree may include D-shaped exit holes in the bark (from adult emergence), “blonding” or lighter coloration of the ash bark from woodpecker feeding (chipping away of the bark as they search for larvae beneath), and serpentine galleries visible through splits in the bark, from larval feeding beneath. Positive identification of an EAB-infested tree may not be possible with these signs individually on their own.

For further information about this insect, please visit: https://ag.umass.edu/fact-sheets/emerald-ash-borer . If you believe you have located EAB-infested ash trees, particularly in an area of Massachusetts not identified on the map provided, please report here: http://massnrc.org/pests/pestreports.htm .

Eriophyid Mites: the family Eriophyidae (gall mites): Noticeable galls on Rhus aromatica (fragrant sumac) have been reported in Middlesex County and observed in Amherst, MA on this particular host. The species suspected is Aculops rhois. A. rhois is known as the poison ivy leaf gall mite, and has been recorded on Toxicodendron and Rhus and previously reported on R. aromatica. This particular eriophyid mite causes galling on leaves that is usually referred to as "bladder" galls. These mites impact early spring foliage and as they develop they leave their galls and initiate more on newly opening leaves. Mite activity decreases as the growing season progresses, yet the galls remain. Not much is known about the life cycle of this particular gall mite.

Eriophyid Mites: the family Eriophyidae (gall mites): Noticeable galls on Rhus aromatica (fragrant sumac) have been reported in Middlesex County and observed in Amherst, MA on this particular host. The species suspected is Aculops rhois. A. rhois is known as the poison ivy leaf gall mite, and has been recorded on Toxicodendron and Rhus and previously reported on R. aromatica. This particular eriophyid mite causes galling on leaves that is usually referred to as "bladder" galls. These mites impact early spring foliage and as they develop they leave their galls and initiate more on newly opening leaves. Mite activity decreases as the growing season progresses, yet the galls remain. Not much is known about the life cycle of this particular gall mite.

No management is generally necessary for eriophyid mites causing bladder galls on leaves. These insect relatives typically cause damage that is at most only aesthetically displeasing, and not particularly damaging to overall plant health. That said, there are some mites in this genus that have been reported to cause economically significant damage in the literature. However, others, such as the Aculops spp. found on maple, are rarely detrimental to the overall health of their hosts.

- Fall Home-Invading Insects: Various insects, such as ladybugs, boxelder bugs, seedbugs, and stink bugs will begin to seek overwintering shelters in warm places, such as homes, throughout the next couple of months. While such invaders do not cause any measurable structural damage, they can become a nuisance especially when they are present in large numbers. While the invasion has not yet begun, if you are not willing to share your home with such insects, now should be the time to repair torn window screens, repair gaps around windows and doors, and sure up any other gaps through which they might enter the home.

- Fall Webworm: Hyphantria cunea is native to North America and Mexico. It is now considered a world-wide pest, as it has spread throughout much of Europe and Asia. (For example, it was introduced accidentally into Hungary from North America in the 1940’s.) Hosts include nearly all shade, fruit, and ornamental trees except conifers. In the USA, at least 88 species of trees are hosts for these insects, while in Europe at least 230 species are impacted. In the past history of this pest, it was once thought that the fall webworm was a two-species complex. It is now thought that H. cunea has two color morphs – one black headed and one red headed. These two color forms differ not only in the coloration of the caterpillars and the adults, but also in their behaviors. Caterpillars may go through at least 11 molts, each stage occurring within a silken web they produce over the host. When alarmed, all caterpillars in the group will move in unison in jerking motions that may be a mechanism for self-defense. Depending upon the location and climate, 1-4 generations of fall webworm can occur per year. Fall webworm adult moths lay eggs on the underside of the leaves of host plants in the spring. These eggs hatch in late June or early July depending on climate. Young larvae feed together in groups on the undersides of leaves, first skeletonizing the leaf and then enveloping other leaves and eventually entire branches within their webs. Webs are typically found on the terminal ends of branches. All caterpillar activity occurs within this tent, which becomes filled with leaf fragments, cast skins, and frass. Fully grown larvae then wander from the webs and pupate in protected areas such as the leaf litter where they will remain for the winter. Adult fall webworm moths emerge the following spring/early summer to start the cycle over again. 50+ species of parasites and 36+ species of predators are known to attack fall webworm in North America. Fall webworms typically do not cause extensive damage to their hosts, but on occasion, this can occur. Nests may be an aesthetic issue for some. If in reach, small fall webworm webs may be pruned out of trees and shrubs and destroyed. Do not set fire to H. cunea webs when they are still attached to the host plant.

- Hickory Tussock Moth: Lophocampa caryae is native to southern Canada and the northeastern United States. There is one generation per year. Overwintering occurs as a pupa inside a fuzzy, oval shaped cocoon. Adult moths emerge approximately in May and their presence can continue into July. Females will lay clusters of 100+ eggs together on the underside of leaves. Females of this species can fly, however they have been called weak fliers due to their large size. When first hatched from their eggs, the young caterpillars will feed gregariously in a group, eventually dispersing and heading out on their own to forage. Caterpillar maturity can take up to three months and color changes occur during this time. These caterpillars are essentially white with some black markings and a black head capsule. They are very hairy, and should not be handled with bare hands as many can have skin irritation or rashes (dermatitis) as a result of interacting with hickory tussock moth hairs. By late September, the caterpillars will create their oval, fuzzy cocoons hidden in the leaf litter where they will again overwinter. Hosts whose leaves are fed upon by these caterpillars include but are not limited to hickory, walnut, butternut, linden, apple, basswood, birch, elm, black locust, and aspen. Maple and oak have also been reportedly fed upon by this insect. Several wasp species are parasitoids of hickory tussock moth caterpillars.

- Spotted Lanternfly: (Lycorma delicatula, SLF) is not known to occur in Massachusetts landscapes (no established populations are known in MA at this time). However, officials with the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources (MDAR) urged residents to check plants for spotted lanternfly. On February 21, 2019 MDAR announced the discovery of a single dead spotted lanternfly adult at a private residence in Boston. As a result of this discovery, officials asked the public to check potted plants they purchase and report any suspicious insects. MDAR reports that this particular individual appeared to have been unintentionally transported this past December in a shipment of poinsettia plants originating from Pennsylvania. Officials also report that there is currently no evidence that this pest has become established in MA. For more information about this finding, please visit the MA Department of Agricultural Resources press release:https://www.mass.gov/news/state-agricultural-officials-urge-residents-to-check-plants-for-spotted-lanternfly .

This insect is a member of the Order Hemiptera (true bugs, cicadas, hoppers, aphids, and others) and the Family Fulgoridae, also known as planthoppers. The spotted lanternfly is a non-native species first detected in the United States in Berks County, Pennsylvania and confirmed on September 22, 2014.

The spotted lanternfly is considered native to China, India, and Vietnam. It has been introduced as a non-native insect to South Korea and Japan, prior to its detection in the United States. In South Korea, it is considered invasive and a pest of grapes and peaches. The spotted lanternfly has been reported from over 70 species of plants, including the following: tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) (preferred host), apple (Malus spp.), plum, cherry, peach, apricot (Prunus spp.), grape (Vitis spp.), pine (Pinus spp.), pignut hickory (Carya glabra), Sassafras (Sassafras albidum), serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.), slippery elm (Ulmus rubra), tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera), white ash (Fraxinus americana), willow (Salix spp.), American beech (Fagus grandifolia), American linden (Tilia americana), American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis), big-toothed aspen (Populus grandidentata), black birch (Betula lenta), black cherry (Prunus serotina), black gum (Nyssa sylvatica), black walnut (Juglans nigra), dogwood (Cornus spp.), Japanese snowbell (Styrax japonicus), maple (Acer spp.), oak (Quercus spp.), and paper birch (Betula papyrifera).

The adults and immatures of this species damage host plants by feeding on sap from stems, leaves, and the trunks of trees. In the springtime in Pennsylvania (late April - mid-May) nymphs (immatures) are found on smaller plants and vines and new growth of trees and shrubs. Third and fourth instar nymphs migrate to the tree of heaven and are observed feeding on trunks and branches. Trees may be found with sap weeping from the wounds caused by the insect’s feeding. The sugary secretions (excrement) created by this insect may coat the host plant, later leading to the growth of sooty mold. Insects such as wasps, hornets, bees, and ants may also be attracted to the sugary waste created by the lanternflies, or sap weeping from open wounds in the host plant. Host plants have been described as giving off a fermented odor when this insect is present.

Adults are present by the middle of July in Pennsylvania and begin laying eggs by late September and continue laying eggs through late November and even early December in that state. Adults may be found on the trunks of trees such as the tree of heaven or other host plants growing in close proximity to them. Egg masses of this insect are gray in color and, in some ways, look similar to gypsy moth egg masses.

Host plants, bricks, stone, lawn furniture, recreational vehicles, and other smooth surfaces can be inspected for egg masses. Egg masses laid on outdoor residential items such as those listed above may pose the greatest threat for spreading this insect via human aided movement.

For more information about the spotted lanternfly, visit this fact sheet: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/spotted-lanternfly .

- Tuliptree Aphid: Illinoia liriodendri is a species of aphid associated with the tuliptree, wherever it is grown. The tuliptree aphid was seen feeding on the undersides of leaves on 7/25/19 and again on 8/21/19 in Amherst, MA. Depending upon local temperatures, these aphids may be present from mid-June through early fall. Large populations can develop by late summer. Some leaves, especially those in the outer canopy, may turn brown or yellow and drop from infested trees prematurely. The most significant impact these aphids can have is typically the resulting honeydew, or sugary excrement, which may be present in excessive amounts and coat leaves and branches, leading to sooty mold growth. This honeydew may also make a mess of anything beneath the tree. Wingless adults are approximately 1/8 inch in length, oval, and can range in color from pale green to yellow. There are several generations per year. This is a native insect. Management is typically not necessary, as this insect does not significantly impact the overall health of its host. Tuliptree aphids also have plenty of natural enemies, such as ladybeetles and parasites.

- Viburnum Leaf Beetle: Pyrrhalta viburni is a beetle in the family Chrysomelidae that is native to Europe, but was found in Massachusetts in 2004. In Amherst, MA on 7/9/19 and again on 7/24/19, adult Viburnum leaf beetles were found mating, feeding, and laying eggs at this location. Females will lay their eggs in pits they chew at the ends of twigs. Eggs overwinter. Adults may also migrate to previously not yet infested plants. Feeding damage from adult Viburnum leaf beetle was observed on 8/15/2019 in Goshen, MA on native Viburnum in a natural setting. This beetle feeds exclusively on many different species of Viburnum, which includes, but is not limited to, susceptible plants such as V. dentatum, V. nudum, V. opulus, V. propinquum, and V. rafinesquianum. Some Viburnum have been observed to have varying levels of resistance to this insect, including but not limited to V. bodnantense, V. carlesii, V. davidii, V. plicatum, V. rhytidophyllum, V. setigerum, and V. sieboldii. More information about Viburnum leaf beetle may be found at http://www.hort.cornell.edu/vlb/ .

Yellowjackets: (Vespula spp.and Dolichovespula spp.) Often times, when we think that we have been “stung by a bee” the true culprit is some type of yellowjacket. Yellowjackets frequently interact with humans at the end of the summer due to a shift in their foraging behaviors. Early in the season, they can act as beneficial insects as they are predators of many pest insects such as caterpillars. These protein resources can be useful to them when rearing their young. Later in the season, they may switch to foods high in carbohydrates or sugars, including nectar and honeydew, but also some of our favorite items to pack during outdoor picnics or cookouts (soda and other sugary treats).

Yellowjackets: (Vespula spp.and Dolichovespula spp.) Often times, when we think that we have been “stung by a bee” the true culprit is some type of yellowjacket. Yellowjackets frequently interact with humans at the end of the summer due to a shift in their foraging behaviors. Early in the season, they can act as beneficial insects as they are predators of many pest insects such as caterpillars. These protein resources can be useful to them when rearing their young. Later in the season, they may switch to foods high in carbohydrates or sugars, including nectar and honeydew, but also some of our favorite items to pack during outdoor picnics or cookouts (soda and other sugary treats).

Unlike European honeybees (Apis mellifera), yellowjackets are capable of stinging multiple times (multiple stings from a single individual). This includes aerial yellowjackets such as the baldfaced hornet and other species in the genus Dolichovespula spp. European honeybees (the workers) can only sting once due to the fact that they have a barbed stinger/ovipositor. This causes the ovipositor to become stuck in the skin, tearing this structure free from the abdomen of the honeybee, thus killing the honeybee. Honeybees are often not aggressive and only attack when otherwise threatened. This may not be the case for yellowjackets.

Be on the lookout for their nests and avoid. Baldfaced hornets and other aerial yellowjackets make aerial nests that are nearly completely covered with a papery shell (except for an opening for entrance/exit of the nest). These can be found in trees and shrubs located up off the ground. Some yellowjackets will also create subterranean nests or nest in cavities of trees, decayed stumps, or associated with buildings. If nests are in areas where these insects are unlikely to interact with humans, they can be left alone. These nests are not used again the following season, and by the first couple of hard frosts, all individuals will be gone. However, if they are close to homes/doorways, walkways, benches, etc. (high traffic areas) management may be necessary, especially if the homeowner/individuals using the property are allergic to stings. The baldfaced hornet nest in these photos was found attached to the entrance of French Hall on the University of Massachusetts campus in Amherst, MA as seen on 8/20/19. (This particular nest has since been removed in preparation for the return of students in this high traffic area.)

Attempts to remove yellowjacket or baldfaced hornet nests should be made at night, or at least very early or very late in the day when temperatures are still cool, activity by the yellowjackets is likely to be low, and the individuals are likely to still be contained (largely) within the nest. Note that although the insects may not be terribly active, any disturbance to the nest/colony will change that. Wear protective clothing (long sleeves and pants tight around wrists and ankles and close-toed shoes or boots, at minimum). Many insecticides are labelled for use against yellowjackets and baldfaced hornets, including products that can be shot into the opening of the nest from many feet away. Note that agitated yellowjackets may leave the nest, looking for the source of aggravation (you), and will be ready to sting. Use extreme caution, and individuals who are allergic to stings should not attempt this. Hire a professional. Again, if the nest is in a location where interaction with people is unlikely, consider leaving it alone until a few hard frosts have hit, at which time the nest can be removed if desired.

Concerned that you may have found an invasive insect or suspicious damage caused by one? Need to report a pest sighting? If so, please visit the Massachusetts Introduced Pests Outreach Project: http://massnrc.org/pests/pestreports.htm .

A note about Tick Awareness: deer ticks (Ixodes scapularis), the American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis), and the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) are all found throughout Massachusetts. Each can carry their own complement of diseases. Anyone working in tick habitats (wood-line areas, forested areas, and landscaped areas with ground cover) should check themselves regularly for ticks while practicing preventative measures. Have a tick and need it tested? Visit the web page of the UMass Laboratory of Medical Zoology (https://www.tickreport.com/ ) and click on the blue Order a TickReport button for more information.

Reported by Tawny Simisky, Extension Entomologist, UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, & Urban Forestry Program

Additional Resources

To receive immediate notification when the next Landscape Message update is posted, be sure to join our e-mail list and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

For a complete listing of upcoming events, see our Upcoming Educational Events page.

For commercial growers of greenhouse crops and flowers - Check out UMass Extension's Greenhouse Update website

For professional turf managers - Check out Turf Management Updates

For home gardeners and garden retailers - Check out home lawn and garden resources. UMass Extension also has a Twitter feed that provides timely, daily gardening tips, sunrise and sunset times to home gardeners, see https://twitter.com/UMassGardenClip

Diagnostic Services

A UMass Laboratory Diagnoses Landscape and Turf Problems - The UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab is available to serve commercial landscape contractors, turf managers, arborists, nurseries and other green industry professionals. It provides woody plant and turf disease analysis, woody plant and turf insect identification, turfgrass identification, weed identification, and offers a report of pest management strategies that are research based, economically sound and environmentally appropriate for the situation. Accurate diagnosis for a turf or landscape problem can often eliminate or reduce the need for pesticide use. For sampling procedures, detailed submission instructions and a list of fees, see Plant Diagnostics Laboratory

Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing - The University of Massachusetts Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory is located on the campus of The University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Testing services are available to all. The function of the Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory is to provide test results and recommendations that lead to the wise and economical use of soils and soil amendments. For complete information, visit the UMass Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory web site. Alternatively, call the lab at (413) 545-2311.

Ticks are active at this time! Remember to take appropriate precautions when working and playing outdoors, and conduct daily tick checks. UMass tests ticks for the presence of Lyme disease and other disease pathogens. Learn more.