A monthly e-newsletter from UMass Extension for landscapers, arborists, and other Green Industry professionals, including monthly tips for home gardeners.

To read individual sections of the message, click on the section headings below to expand the content:

Hot Topics

Irrigation Tips

Despite the deluge of rainfall many parts of southern New England have received recently, July and August are typically our driest months. If the remainder of the summer reverts to more typical low rainfall patterns, here are some irrigation tips to keep in mind. As always, remember to factor in natural rainfall when making any decisions to provide supplemental irrigation.

- Irrigating during early morning or evening is most efficient. Evaporation is greatest at midday, which could mean that much of the water is lost before it reaches the plants. Wind is generally often lowest in the morning.

- Use drip irrigation or soaker hoses when possible. Overhead irrigation frequently results in watering of non-plant surfaces and interception by plant canopies.

- Infrequent deep irrigation is most effective for established plants

- Newly installed plants will need more frequent irrigation while roots establish.

- A 2-4” layer of mulch helps reduce evaporation and insulates plant roots. Keep mulch away from the base of plants.

- Control weeds to reduce competition for water.

- Perform irrigation system maintenance.

- Be aware of, and follow, your local town or municipality water regulations.

- Keep in mind that landscapes typically require one inch of water per week (including rainfall). Unsure of what your system or sprinkler is applying? You can use a rain gauge and see how much water is collected in a certain period of time (30 minutes for example). Use multiple rain gauges if possible to understand if you have good uniformity of application, or make sure the rain gauge is located in an “average area”.

Mandy Bayer, Extension Assistant Professor of Sustainable Landscape Horticulture, UMass Stockbridge School of Agriculture

Featured Fungus

Guignardia on Grapes and Boston Ivy

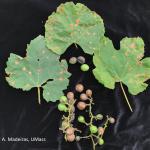

The fungus Guignardia bidwellii causes black rot, the most common disease encountered by backyard grape growers. It is also common on Boston ivy (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), on which it is more often called Guignardia leaf spot.

G. bidwellii causes round, tan leaf lesions with dark purple to brown margins on the leaves of host plants. Young leaves and shoots are especially vulnerable to infection. Severe infection may cause leaf deformity. Lesions may also girdle petioles and shoots, resulting in wilt and leaf drop. Affected grapes turn brown and soft at first, but within a few days they become hard, black, shriveled structures called mummies. Small, round, black fruiting bodies called pycnidia are produced on the lesions and may be visible with a hand lens. Pycnidia produce asexual spores known as conidia.

The fungus overwinters in infected plant tissues. In spring, fruiting bodies called pseudothecia produce ascospores via sexual reproduction. These spores are blown by wind onto the surfaces of developing plant tissues. Warm, wet or humid weather is conducive to spore germination and infection. New lesions form, and pycnidia produce a new round of spores which are spread by splashing rain. The disease cycle may continue as long as environmental conditions are conducive. Fruit infection occurs within approximately 4-6 weeks after bloom.

Sanitation is the most crucial element of a successful disease management program. Remove infected canes and fruit clusters from vines. Rake up and dispose of fallen leaves and fruit mummies. In addition, mulch may be used to cover any remaining plant debris and prevent spores released in spring from reaching new leaves. G. bidwellii affects other members of the family Vitaceae, including wild grapes, porcelainberry (Ampelopsis brevipedunculata), and Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia). These reservoir hosts should be managed as well as possible in the landscape.

Reduce humidity and increase air circulation in the plant canopy by removing canes, vines, or leaves. All cultivars of Vitis vinifera are highly susceptible to black rot, while some hybrids and other Vitis species are less susceptible. No species or cultivar of grape or Boston ivy is completely resistant.

It is best to consult a professional applicator when considering pesticide use in residential settings; however, there are a few fungicides available to homeowners. These products must be labeled specifically for use on grapes if they are to be used for that purpose. More choices are available for ornamentals such as Boston ivy. In grapes, preventative applications of protectant fungicides should begin shortly before bloom and be repeated at the intervals recommended on the label until approximately 4-6 weeks post bloom. Follow all label directions carefully. Be aware that no fungicide treatment is 100% effective.

Angela Madeiras, UMass Extension Diagnostic Technician: Floriculture, Vegetable Crops, and Turf

Q&A

Q: I live in Berkshire County, MA and Lymantria dispar caterpillars were everywhere in my yard! What should I do to protect my trees and shrubs?

The Entomological Society of America has announced that it is undertaking an effort to remove offensive and derogatory language from insect common names.This includes the common name for the insect formerly known as gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar) and others. Replacing offensive names is consistent with the values of the University of Massachusetts with regard to diversity and inclusion. UMass Extension is working on removing this terminology from our online resources and reporting, but warn that some archival materials may continue to include such language. For more information, visit: https://www.entsoc.org/entomological-society-america-discontinues-use-gypsy-moth-ant-names.

A: The caterpillar stage of the non-native moth, Lymantria dispar, has reportedly been very active and noticeable in certain parts of Berkshire County, Massachusetts in 2021. Reports have come in to UMass Extension from Alford, Great Barrington, Richmond, South Egremont, and Williamstown. This has come as a bit of a shock for some people living in these areas, as they were fortunate enough to be almost entirely spared during the peak of the most recent outbreak in other parts of eastern, central, and western Massachusetts in 2017 when 923,000 acres were defoliated in those locations, most of which were outside of Berkshire County. There are additional reports of noticeable Lymantria dispar activity in other parts of New England at this time, including but not limited to certain sections of: Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Vermont, as well as parts of New York.

Unfortunately, once L. dispar caterpillars reach a certain size, they are quite robust and very difficult to manage. This often corresponds with when they are most noticeable to us, and when defoliation from their feeding is most visible (and nearly complete for the current season). The good news is: caterpillars typically begin to pupate by the third week in June in Massachusetts, and adult moths may be seen by the end of June or the beginning of July. Once pupation occurs, feeding from Lymantria dispar stops for the current year. (Only the caterpillar stage feeds on the leaves of its host plants, which include but are not limited to: oak, poplar, willow, birch, witch hazel, blueberry, and many other deciduous trees and shrubs. When populations are high enough, L. dispar also feeds on conifers including eastern white pine, hemlock, and spruce.)

At this time in July, most Lymantria dispar caterpillars have pupated, and adult male moths may be seen flying in search of females. Adults will mate, and the female moths will lay brown/tan egg masses on nearly any flat surface, as seen here in Berkshire County, MA on 7/7/2021.

At this time in July, most Lymantria dispar caterpillars have pupated, and adult male moths may be seen flying in search of females. Adults will mate, and the female moths will lay brown/tan egg masses on nearly any flat surface, as seen here in Berkshire County, MA on 7/7/2021.

More good (mostly) news: most deciduous trees (as long as they are otherwise healthy and not stressed by other factors) can usually survive a single year of defoliation and may even send out a second set of leaves before the fall. Conifers on the other hand, unfortunately, are not usually so tolerant (even of a single year of defoliation). Multiple, consecutive years of defoliation can cause branch dieback and mortality of entire trees in some cases. Watering trees (when able and if necessary) and other actions to reduce additional stress at this time may be helpful for landscape specimens.

For next year: This coming fall and winter (after L. dispar females have completed their egg laying for 2021), scout your property and surrounding areas for overwintering egg masses. If there are a lot of egg masses visible, make plans with your local professional arborist and licensed or certified pesticide applicator to treat valuable specimen trees (especially those that were defoliated in 2021) when Lymantria dispar caterpillar eggs hatch and young caterpillars begin feeding in 2022. If caught early (when caterpillars are feeding and under approximately ¾ inch in length), a reduced risk option for managing Lymantria dispar is to apply Bacillus thuringiensis kurstaki to leaves of host plants that are being fed upon. But this must be done when caterpillars are still small and actively feeding. (Any lingering caterpillars present this season are too big to be effectively managed by Btk.) Another reduced risk active ingredient to consider next year, if needed, would be spinosad.

In the meantime, we can hope that the fungus (Entomophaga maimaiga) and the NPV virus will catch up with the population in Berkshire County and drop it below damaging levels, such as what was seen in the rest of Massachusetts in recent years. There may be some tree mortality, which is unfortunately not uncommon, but our forests have dealt with this insect since the 1860's - and they have been resilient. For more information about Lymantria dispar and how to identify caterpillars killed by the fungus and the virus, visit: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/insectxaminer.

Q: I’m looking for help. I just noticed that I have MANY of these bugs in my vegetable garden. I lifted a pot that I had placed there last night and found even more. I don’t know if they are harmful to my veggies (will eat my produce) and if so, how I should safely deal with them?

A: What you have there are actually millipedes (Class: Diplopoda), so these are relatives of the insects but not insects themselves. Millipedes are characterized by having two pairs of legs per body segment, a characteristic that can be used to distinguish them from centipedes who possess one pair of legs per body segment. Millipedes feed on decaying organic matter and typically do not feed on or cause harm to living plants (including in vegetable gardens) unless the soil dries to the point where they may begin to feed on roots for moisture. Some damage to soft-stemmed plants has been reported in greenhouses.

Minimizing moisture and removing debris that trap in moisture (such as old pots, logs, rocks, boards, compost piles, and other items) near the garden may deter them from living in the area. Pesticides are not required to manage millipedes, and are often ineffective. Millipedes also provide a useful ecosystem service as macrodecomposers that accelerate nutrient cycling.

Q: I found this adelgid-like insect on eastern white pine (Pinus strobus). A bunch of the saplings at my property in NH are loaded. Should I worry?

A: The pine bark adelgid (Pineus strobi) will colonize the bark, needles, and candles of eastern white pine, Austrian pine, and Scotch pine. All life stages of this insect occur on pine hosts, unlike other species in the genus Pineus which alternate between pine and spruce. The pine bark adelgid overwinters in an immature stage on the bark of its host plant, and in the spring as temperatures warm they will begin to feed and secrete large amounts of white, waxy, woolly material over themselves, similar in appearance to the hemlock woolly adelgid. Mature females lay eggs which will hatch into crawlers, as well as winged individuals that disperse. Wingless forms may settle on the tree and reproduce repeatedly. Multiple generations occur per year.

Healthy, established, and mature trees are rarely impacted by the pine bark adelgid. Therefore, chemical management is rarely warranted. In high populations, entire trunks of trees may be coated in the white woolly material. If you find this unsightly, it may be sprayed off of the trunk with a strong stream of water from a hose. Beneficial insects also feed on pine bark adelgid, including but not limited to hoverfly larvae and lady beetle adults and larvae.

Tawny Simisky, Extension Entomologist, UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, & Urban Forestry Program

Is Glufosinate a Suitable Substitute for Glyphosate??

Landscape and turf professionals are being asked by their customers if there is an alternative available for glyphosate. These requests occur due to the perceived health risks associated with glyphosate. Glufosinate is commonly suggested as a one-to-one replacement for glyphosate. The most common glufosinate products available are FinaleTM (EPA reg # 7969-444) and Cheetah ProTM (EPA reg # 228-743). Like glyphosate, glufosinate is a non-selective, postemergence herbicide. Despite sharing its non-selective, postemergence characteristic with glyphosate, glufosinate has several very different characteristics. These characteristics lead to differences in use patterns and weed control.

Characteristics of glufosinate

Behavior in soil1

- Degradation: Rapidly degraded by soil microbes to 3-methyl phosphinico-proprionic acid and ultimately CO2.

- Persistence: Soil half-life is short, typical 7 days.

- Mobility: Highly mobile; despite high leaching potential, glufosinate has not been detected below 12 cm in field studies, likely due to its rapid microbial degradation.

Behavior in plants1

- Absorption and translocation: A rain-free period of 6 hours is required for maximum efficacy. Little or no root absorption occurs. Very little to no movement occurs via the xylem or phloem.

- Mechanism of action: Inhibits glutamine synthetase. The enzyme glutamine synthetase converts glutamate and ammonia to glutamine and inhibition of this enzyme results in an accumulation of ammonia in the plant. Ammonia destroys cells and directly inhibits photosystem I and photosystem II reactions.

- Symptomology: Chlorosis and wilting usually occur within 3 to 5 days, followed by necrosis in 1 to 2 weeks. Rate of symptomology development is increased by bright sunlight, high humidity, and soil moisture.

1. Soil and plant behavior characteristics of glufosinate from Weed Science Society Herbicide Handbook Tenth Edition 2014, published by Weed Science Society, 810 E. 10th Street, Lawrence, Kansas 66044-8897. ISBN 978-0-615-98937-2

|

Characteristic |

Glyphosate |

Glufosinate |

|

Translocation: movement within plant |

strong translocation2 a translocated herbicide |

very limited translocation2 a contact herbicide |

|

Effect on summer annual life cycles weeds

|

excellent control |

fair to good control when weed is young |

|

Effect on winter annual life cycles weeds

|

excellent control on all growth stages |

fair to good control on seedling and immature weeds |

|

Effect on simple/solitary perennial life cycle weeds (lacking vegetative propagation) |

excellent control |

fair to poor, good control when young |

|

Effect on creeping/spreading perennial life cycle weeds (vegetative propagation) |

excellent control |

good to fair control when on weed seedlings and/or before weed develops underground vegetative propagules (rhizomes, creeping roots, well-developed taproot) |

|

Appropriate for turf renovation

|

Yes |

No |

|

Appropriate for landscape directed spray |

Yes, beware of drift injury to leaves and to bark on woody trees and shrubs. |

Yes, drift injury risk lower than glyphosate; can cause sunken bark cankers on young thin-barked landscape ornamentals. Drift to leaves not likely to kill ornamentals. |

|

Appropriate for invasive plant management |

excellent on invasive plants that are controlled by this herbicide |

good on seedlings only, otherwise poor, most appropriate for summer annual and biennial invasives such a Japanese stiltgrass and garlic mustard. |

2. Translocation characteristics from Weed Science Society Herbicide Handbook Tenth Edition 2014, published by Weed Science Society, 810 E. 10th Street, Lawrence, Kansas 66044-8897. ISBN 978-0-615-98937-2

US Department of Environmental Protection - More information on glyphosate’s federal and state registration and status can be found at https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/glyphosate.

UMass Extension - UMass Extension recognizes that there is public debate about glyphosate. Our relevant expertise is in agriculture and horticulture, not in public health, medicine, or environmental contamination. For this reason, the information presented above focuses on known data regarding the efficacy for weed control of a variety of active ingredients. These active ingredients are registered with the EPA and the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources and have met the public health and environmental standards developed by those agencies. UMass Extension is committed to the principles and practices of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) and much of our research and education is dedicated to reducing the use of pesticides.

Randy Prostak, UMass Extension Weed Specialist

Garden Clippings Tips of the Month

July is the month to . . . .

- Protect yourself when working outdoors. Make sure you drink plenty of water. Wear a wide brimmed hat and long sleeves to protect skin from the sun or use sunscreen. Use repellents to protect against mosquitoes and treat your clothing with permethrin to protect against ticks.

- Evaluate the landscape for hot spots that may benefit from shade in the future. While July is not the time to plant trees and shrubs, it is good time to identify those areas that would greatly benefit from the shade provided by planting a tree. Shading a structure such as a home can result in big energy savings by reducing cooling costs.

- Conserve water by properly watering. For established plants, try to use deep and infrequent watering. Deep means watering until the root zone is saturated - this typically requires physically checking the soil to a depth of about 8 inches. Infrequent means allowing the soil to dry between watering. New plantings that are not established require more frequent watering; this can be several times a week during the hottest/driest periods.

- Shocked by last summer’s water bill? Consider allowing the lawn to go summer dormant. Cool season grasses will naturally go dormant under high heat or dry conditions and revive when cooler moisture conditions return at the end of summer. Reduce mowing and heavy traffic on summer dormant lawns to avoid damaging the crowns of the plants.

- Get the weeds before they go to seed. A year of seed equals ten of weeds! Weeds that are able to go to seed add significantly to the weed seed bank (reserve of viable weed seed in the soil). In many cases, a single weed plant is capable of producing thousands to tens of thousands of seeds. Common purslane is a good example of a weed that has been reported to produce 240,000 to more than a million seeds on a single plant and the seeds can remain viable for up to 15 years or more.

- Seeing insect damage on plants in the garden but no insects? Take a stroll at night with a headlamp - several insects that feed on plants are nocturnal. Asiatic garden beetle is one such insect that feeds at night in July and hides in the soil during the day. Asiatic garden beetle has similar feeding habits to Japanese beetle, feeding on many different ornamentals and edible plants.

- Monitor for diseases in the vegetable garden. July is often the month that diseases like early blight and Septoria leaf spot show up on tomato and powdery mildew on cucurbits (squash, melon, cucumber, etc.). Catching diseases early is crucial in having management success.

- Early blight and Septoria leaf spot on tomato are classic leaf spot diseases of tomato that begin on the older, lower leaves. These diseases cause spots that result in yellowing leaves that eventually wither as the disease works its way up the plant. To manage these diseases in the home garden, avoid overhead watering, use a mulch (plastic or natural) at planting, improve air circulation by pruning plants or use proper spacing (wide rows), and keep fertility up. Once disease symptoms are seen, copper-based fungicides provide reliable control.

- Powdery mildew often shows up in late July on squash, pumpkin, cucumber and melons. Powdery mildew is unique in that it can infect plants and spread rapidly when there is high humidity, but the leaves aren’t wet. Managing powdery mildew is difficult for this reason. Consider using biopesticides with the active ingredient Bacillus subtilis preventatively. Once powdery mildew appears, consider using potassium bicarbonate, copper or a botanical oil such as neem. Next year consider using PMR (powdery mildew resistant) cultivars.

- Deadhead and prune container plantings. Container plantings need constant attention during the hottest times of the year to flourish. Make sure watering is consistent - drastic ups and downs in watering containers often stresses plants and results in the older leaves yellowing and falling off. Use a soluble fertilizer regularly or a timed-release fertilizer to make sure the plants in the container are being continually fed. Prune and deadhead plants on a regular basis to keep up the container’s appearance; waiting until plants have stretched or are overgrown before pruning often results in poor regrowth.

Russ Norton, Cape Cod Cooperative Extension

Tick Season Is In Full Swing…

Officially it is summer and people are engaged in a lot of outdoor activities, particularly as we navigate out of the pandemic. And in New England we have to be mindful that there is a continuous exposure risk for a tick bite. Check out the tick family portrait to the left. On the far right is an adult female deer tick and an adult male is in the center - the adult stage tick season finished in late May. On the left is a nymph stage tick and these will be active into August.

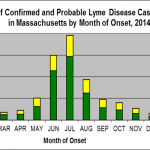

A nymph is the size of a poppy seed - it can easily elude a tick check. This is reflected in the case data shown in the chart below (MA Dept. Public Health). The nymph stage is responsible for 85% of tick-borne diseases because they so often go undetected. However, note that there are cases of Lyme disease every month of the year.

And it’s not just about Lyme disease anymore. Other significant tick-borne diseases are babesiosis and anaplasmosis. We see a certain level of co-infection where ticks are carrying more than one pathogen.

A personal protection plan is very straightforward. When you are in tick habitat, which could be in the woods or at the edge of your backyard, wearing light color long pants (light colors make it easier to spot any ticks) and shoes (vs. sandals) is a start. When you come back indoors, do a tick check and throw the clothes in the dryer for 20 minutes.

Repellents are important…skin repellents containing DEET or picaridin are effective. Avoid “all natural” products - there is no testing that shows they are safe or effective (ex. certain “minimum risk pesticides” are exempt from the EPA’s registration, labelling, and testing requirements: https://www.epa.gov/minimum-risk-pesticides).

From my standpoint, the most effective tool in the box is permethrin treated clothing and footwear. It not only repels but actually kills the tick. You can find this product at garden centers and sporting good stores. For more information, Cape Cod Cooperative Extension has a video on the ins and outs of permethrin, which is part of a ten part series about ticks and tick protection, at https://www.capecodextension.org/ticks/.

Enjoy the outdoors, be tick aware, and stay tick safe.

Larry Dapsis, Cape Cod Cooperative Extension Entomologist

Upcoming Events

For more details and registration options for any of these events, go to the UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, and Urban Forestry Program Upcoming Events Page.

-

July 21 - Turf Research Field Day - live and in person! South Deerfield, MA

Credits: 1.5 pesticide credits for categories 37, 49, and Applicator's/Core License; .25 CGCS, 1 MCH, and 4 AOLCP credits available. MCLP and CSFM credits requested.

More details at https://ag.umass.edu/turf/events/2021-umass-turf-research-field-day -

Sept 22 - Ornamental Tree and Shrub ID & Insect Walk - in person, Berkshire Botanical Garden, Stockbridge MA

Credits: 1 pesticide credit for categories 36 and Applicator's/Core License; 1 MCA, 1 MCLP. and 1 MCH credits available; ISA credit requested.

Pesticide Exam Preparation and Recertification Courses

These workshops are currently being offered online. Contact Natalia Clifton at nclifton@umass.edu or go to https://www.umass.edu/pested for more info.

InsectXaminer!

Episodes so far featuring gypsy moth, lily leaf beetle, euonymus caterpillar, and imported willow leaf beetle can be found at: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/insectxaminer

TickTalk with TickReport Webinars

To view recordings of past webinars in this series, go to: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/ticktalk-with-tickreport-webinars

Additional Resources

For detailed reports on growing conditions and pest activity – Check out the Landscape Message

For professional turf managers - Check out our Turf Management Updates

For commercial growers of greenhouse crops and flowers - Check out the New England Greenhouse Update website

For home gardeners and garden retailers - Check out our home lawn and garden resources.

Diagnostic Services

Landscape and Turf Problem Diagnostics - The UMass Plant Diagnostic Lab is accepting plant disease, insect pest and invasive plant/weed samples . By mail is preferred, but clients who would like to hand-deliver samples may do so by leaving them in the bin marked "Diagnostic Lab Samples" near the back door of French Hall (please note that visitors are not allowed inside the building). The lab serves commercial landscape contractors, turf managers, arborists, nurseries and other green industry professionals. It provides woody plant and turf disease analysis, woody plant and turf insect identification, turfgrass identification, weed identification, and offers a report of pest management strategies that are research based, economically sound and environmentally appropriate for the situation. Accurate diagnosis for a turf or landscape problem can often eliminate or reduce the need for pesticide use. See our website for instructions on sample submission and for a sample submission form at https://ag.umass.edu/services/plant-diagnostics-laboratory. Mail delivery services and staffing have been altered due to the pandemic, so please allow for some additional time for samples to arrive at the lab and undergo the diagnostic process.

Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing - The UMass Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Lab is accepting orders for routine soil analysis and particle size analysis ONLY (please do not send orders for other types of analyses at this time). Send orders via USPS, UPS, FedEx or other private carrier (hand delivered orders cannot be accepted at this time). Processing time may be longer than usual since the lab is operating with reduced staff and staggered shifts. The lab provides test results and recommendations that lead to the wise and economical use of soils and soil amendments. For updates and order forms, visit the UMass Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory web site.

Tick Testing - The UMass Center for Agriculture, Food, and the Environment provides a list of potential tick identification and testing options at: https://ag.umass.edu/resources/tick-testing-resources.