A monthly e-newsletter from UMass Extension for landscapers, arborists, and other Green Industry professionals, including monthly tips for home gardeners.

To read individual sections of the message, click on the section headings below to expand the content:

Hot Topics

Bacterial Leaf Spots

Warm temperatures, high humidity, and abundant rainfall this July created perfect conditions for the bacteria that cause leaf spots on plants. Bacterial leaf spots have been observed on annuals, perennials, and vegetables in the area this summer.

Most plant pathogenic bacteria do not survive for very long in the soil; however, they can survive the winter in infected plant tissue. They are released into the soil as the infected tissue degrades. In spring and summer, bacteria may be splashed up from the soil by rainwater or irrigation. When they land on a susceptible plant leaf with a wet surface, they enter the leaf through natural openings such as stomata and hydathodes, or through small wounds. Bacteria may also be spread from plant to plant by splashing rain or on hands or tools.

Bacterial leaf spots are most often caused by species of Pseudomonas and Xanthomonas. The lesions they create are sometimes referred to as angular leaf spots because they are limited by leaf veins. Lesions may begin as water-soaked spots that turn brown and are often surrounded by haloes of yellow tissue. In severe cases, lesions may coalesce and cover large portions of the leaf. Defoliation may occur, and flowers may also show symptoms. Plants are seldom killed, but affected plants are considered unsightly and unsaleable.

Most plant pathogenic bacteria do not survive for very long in the soil; however, they can survive the winter in infected plant tissue. They are released into the soil as the infected tissue degrades. In spring and summer, bacteria may be splashed up from the soil by rainwater or irrigation. When they land on a susceptible plant leaf with a wet surface, they enter plant tissues through natural openings such as stomata and hydathodes, or through small wounds.

Sanitation is the most important If you are fond of zinnias - consider growing resistant cultivars such as ‘Crystal’ or ‘Star’.

Angela Madeiras, UMass Extension Diagnostic Technician: Floriculture, Vegetable Crops, and Turf

Q&A

Q: Every year my tomato plants suffer from disease. How do I stop it?

A: There are many diseases that affect tomatoes; however, the two most common diseases in home vegetable gardens are early blight (Alternaria solani) and Septoria leaf spot (Septoria lycopersici). These two diseases are similar in symptoms and basic epidemiology. Symptoms start as a few spots on lower leaves, steadily progressing with more and more spots, causing leaves to yellow and eventually wither. Symptoms work up the plant, leaving only healthy leaves at the very top of the plant. Early blight and Septoria leaf spot impact plant health, yield and fruit quality.

The diseases can be introduced into the garden on transplants and seed. However, infected debris in the soil from previous crops and hosts is the most significant inoculum source. Early infections occur from conidia (asexual spores) splashed up from the infected debris in the soil by rain or irrigation onto lower leaves. Infections can then rapidly produce new spores that are further spread by rain, irrigation, or people (septoria) or by wind (early blight). Disease progression can be quite rapid under ideal conditions, which is when it is warm and wet.

Success in managing these diseases require attention to several cultural practices.

- Rotate out of solanaceous crops for at least two years.

- Purchase disease free plants and seed – inspect transplants for spots before purchasing or planting.

- Use mulches (plastic or natural) at planting – this creates a barrier between the soil where the disease overwinters and the susceptible tomato leaves.

- Use appropriate spacing – tomatoes should be grown in rows with sufficient room to facilitate rapid drying of foliage; standard row spacing is 5 feet or more between rows.

- Improve air flow – don’t allow weeds to grow in the row or between rows. Remove unnecessary suckers.

- Use drip irrigation – avoid irrigation that wets the foliage.

- Fertilize properly – follow soil test recommendations, keep plants growing vigorously, consider supplemental fertilization around mid-summer .

- Use protective fungicides such as copper hydroxide at regular intervals.

Resources for more information:

- https://ag.umass.edu/vegetable/fact-sheets/recognizing-tomato-blights

- https://ag.umass.edu/vegetable/fact-sheets/solanaceous-early-blight

- https://ag.umass.edu/vegetable/fact-sheets/solanaceous-septoria-leaf-spot

Q: How can I control rabbits? They’re eating all my plants!

A: Wildlife is generally desirable in the landscape, however in some instances wildlife can become a nuisance. Rabbits are a good example of the wildlife conundrum, especially when damage to gardens, shrubs and trees occurs. Massachusetts is home to both the New England cottontail and the eastern cottontail. The eastern cottontail is more abundant and more likely to be observed in the urban and suburban landscape. The eastern cottontail is an herbivore that is active year-round and has a variable diet, feeding on herbaceous plants during the growing season and on bark and buds during the dormant season. Eastern cottontails typically inhabit areas that provide cover adjacent to open areas of herbaceous plant material. The typical home landscape often provides good habitat.

Management is likely to depend on how much rabbit pressure exists. The basic management strategies are exclusion and repellents. Exclusion is by far the most effective method of reducing damage to plants. For woody plants, exclusion is easily achieved by making cages that surround the lower portion of the tree or shrub. Cages should be placed around woody plants in fall and removed in spring when herbaceous plants are growing. Hardware cloth makes a good cage - holes up to 1 inch will protect against rabbits. If voles are also present, hardware cloth with 1/4 inch or 3/8 inch holes is desired. Cage heights of 2-3 feet are adequate.

Fencing is another exclusion method that works great for excluding rabbits from vegetable gardens and flower gardens. Metal fencing 3 feet tall with holes of about 1 inch are suitable for excluding rabbits. The fence should be slightly buried to avoid rabbits from going under the fence. Avoid plastic fencing which is easily gnawed through by rabbits. Metal fencing is not necessarily aesthetically pleasing but, combined with other fencing such as picket fencing, makes it nearly unnoticeable. Before choosing a fence option, consider pressure from other pests; a rabbit fence will not exclude deer or woodchucks. Electric fence options are suitable for temporary situations.

Repellents are the other major category of rabbit management options. Repellents work by taste and/or smell and include active ingredients like dried blood, capsaicin, eggs, and herbal oils. The effectiveness of repellents can be variable. Variability of repellents comes from several factors including the rabbit pressure, application interval, plant susceptibility and product efficacy. In a trial conducted by Williams and Short, no repellent was found as effective as exclusion fencing.

Other options include scare devices like scary-eye balloons and scarecrows. While these may provide some brief control, rabbits as well as other critters quickly become adapted to such tactics. Changes in habitat such as reducing areas of cover and nesting, increasing habitat for predators, or even adding a dog to the landscape may reduce the number of rabbits but is unlikely to save susceptible plants. Growing areas of desirable forage such as clover or alfalfa has also been suggested to lure rabbits away from valuable annuals and perennials. Beware however, this can easily backfire by attracting more rabbits and lead to winter rabbit damage when the forage runs out.

While the above options may provide some protection, a combination of approaches is likely needed. Consider adding more of the plants that aren’t eaten by rabbits in your area. Be cautious with lists of rabbit resistant plants online; while they provide some good starting points, the information is highly anecdotal and maybe different where you are.

Russ Norton, Cape Cod Cooperative Extension

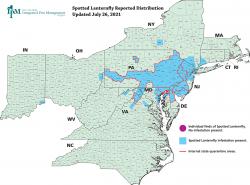

Summer Signs of Spotted Lanternfly

Summer is in full swing, and for states with active infestations, that means invasive spotted lanternfly nymphs (Lycorma delicatula, “SLF”) are well on their way to adulthood. Though this pest is not yet established in Massachusetts, individual finds have been spotted in several counties in Massachusetts. Unfortunately, SLF is an excellent hitchhiker, which means there is a high risk of it being unintentionally introduced into Massachusetts. Read below to learn what you need to look for this time of year, and what you can do to prevent SLF from spreading in our state. If you missed the first article in this series on SLF, you can find it in Hort Notes Vol. 32:2.

By late July, SLF nymphs are at either their third or fourth stage of development (instar). The third instar is larger than the previous two (about ¼ of an inch long), but is still black with white spots. Younger instars have smaller mouthparts (proboscis) and therefore usually go after the more tender leaves and stems on trees and shrubs. Look for them on seedlings, saplings, and succulent new growth of tree of heaven (their preferred host), grape (cultivated and wild), maple, black walnut, and rose. They will also feed on non-woody plants, including hops and common garden vegetables such as basil, cucumber, and melon.

By late July, SLF nymphs are at either their third or fourth stage of development (instar). The third instar is larger than the previous two (about ¼ of an inch long), but is still black with white spots. Younger instars have smaller mouthparts (proboscis) and therefore usually go after the more tender leaves and stems on trees and shrubs. Look for them on seedlings, saplings, and succulent new growth of tree of heaven (their preferred host), grape (cultivated and wild), maple, black walnut, and rose. They will also feed on non-woody plants, including hops and common garden vegetables such as basil, cucumber, and melon.

The fourth and final instar of SLF changes appearance dramatically, becoming bright red with black and white spots. Fourth instar nymphs, which are typically about ½ inch long, may begin to show a preference for tree of heaven and grape, which are the favored host plants of adults, but it’s best to also check other potential host plants in an area, including birch, blueberry, cherry, elm, sycamore, and willow.

All life stages of nymphs are strong jumpers, which means they may leap away if you try and approach them! The tendency of the nymphs to seek out newer, more succulent growth on trees combined with their lack of wings means they’re often found crawling up trees and plants, usually swarming in large numbers. Another indicator of an SLF infestation on host trees is oozing sap on trees and buildup of the lanternfly’s waste product – a sticky substance called honeydew. The honeydew will be white when it accumulates, and promotes the growth of black sooty mold.

All life stages of nymphs are strong jumpers, which means they may leap away if you try and approach them! The tendency of the nymphs to seek out newer, more succulent growth on trees combined with their lack of wings means they’re often found crawling up trees and plants, usually swarming in large numbers. Another indicator of an SLF infestation on host trees is oozing sap on trees and buildup of the lanternfly’s waste product – a sticky substance called honeydew. The honeydew will be white when it accumulates, and promotes the growth of black sooty mold.

In all life stages, the spotted lanternfly is an adept hitchhiker. Just as the nymphs can cling to vertical or upside-down surfaces on plants, they can cling to mobile objects such as shipping containers or vehicles. In fact, every lanternfly found so far in Massachusetts has been the result of them hitchhiking in vehicles or in shipments of goods from an infested area in another state. If you’re traveling to an infested state, it’s a good idea to check your vehicle for hitchhiking SLF.

By the time you read this in August, adult spotted lanternflies will have emerged in warmer southern states like Virginia and Pennsylvania, and fourth instar nymphs will have emerged in Connecticut, so it’s possible they could be hitching rides further north. Keep your eyes out for an article in next month’s Hort Notes to learn more about identifying adult spotted lanternfly!

You download MDAR's Best Management Practices for Nurseries and Landscapers for your own reference, as well as printing them out to distribute to customers or other colleagues in the field. You can also print out MDAR's mini-poster for display and order free outreach materials to help you identify spotted lanternfly and help teach others what to look for. If you think you’ve found a spotted lanternfly nymph or adult, make sure to report it to MDAR.

Joshua Bruckner, Forest Pest Outreach Coordinator, Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources

Garden Clippings Tips of the Month

August is the month to . . . .

-

Keep deadheading perennials. Deadheading keeps plants tidy and encourages rebloom. Container annuals should continue to be watered, fertilized, and trimmed as needed to extend summer color.

-

Divide spring and summer blooming perennials. Late August into September is a good time to divide spring and summer blooming perennials to give plants time to establish roots before the ground freezes. Peony, Siberian iris, oriental poppy, phlox, lilies, and flowering onion can all be divided in fall.

-

Order bulbs for fall planting. Spring blooming bulbs such as tulip and daffodil should be planted in October and November before the ground freezes. Other bulbs to consider are alliums, fritillaria, crocus, muscari, and snowdrops.

-

Remove diseased foliage and plants. Diseased plants and plant parts should be removed from the landscape so that these diseases do not reinfect or spread. Dispose of in the trash or bury onsite.

-

Keep up with weeding! It is best to remove weeds before they go to seed. Be sure not to dispose of weeds in a compost pile that will be returned to the garden.

-

Assess the yard for spots that need a pop of color. Late summer blooming plants include sedum, lavender, panicle hydrangea, aster, hibiscus, monarda, agastache, potentilla, and Enryngium.

-

Plant cool season crops such as broccoli and lettuce. Consider adding edibles with ornamental appeal, such as colorful leafy lettuce, as an annual in landscape beds.

-

Start planning for fall planting. September and October are good times for planting trees and shrubs.

Mandy Bayer, Extension Assistant Professor of Landscape Horticulture, UMass Amherst

Determining Baseline Pesticide Levels in Bee-Collected Pollen

For more info on new bee research, check out The Research Buzz – a quarterly column summarizing the latest in pollinator research. It is published in the Massachusetts Beekeeping Association newsletter, and also on the UMass Extension website.

As part of the annual USDA honey bee survey, state bee inspectors from 39 states gather pollen and bee samples from large-scale apiaries. These samples are then assessed for diseases and pesticides in order to track honey bee health trends. Learn more about the survey at https://ushoneybeehealthsurvey.info/ and explore the data at https://research.beeinformed.org/state_reports.

In a paper published earlier this year, researchers analyzed pollen pesticide results from seven survey years (2011-2017). They found that >80% of samples contained at least one pesticide, with an average of 2.78 pesticides per sample. Overall, beekeeper-applied miticides were the most commonly detected pesticide type, followed by insecticides and fungicides. The detected pesticides with the highest toxicity to bees were insecticides (especially neonicotinoids), miticides, one fungicide (THPI), and one herbicide (atrazine). Over all seven years, insecticide prevalence decreased but herbicide and fungicide prevalence increased. Interestingly, higher fungicide concentrations were correlated with a higher risk of the honey bee gut pathogen Nosema, brood disease and queen problems. The authors hypothesize that fungicides may destroy beneficial colony fungi, leaving bees vulnerable to pathogens like Nosema.

Why is this research important?

Establishing baseline national information on in-hive pesticides will allow us to detect future trends, and can inform recommendations for growers and beekeepers. The results from this study are consistent with other pollen pesticide surveys, including one conducted in MA in 2018 (read about it at https://ag.umass.edu/resources/pollinators/research-projects-at-umass/2018-massachusetts-hobbyist-health-survey). The fact that this study finds a link between fungicides and Nosema is especially interesting because, even though fungicides are not very toxic to bees directly, researchers are beginning to realize that they may impact hive health in significant ways. Knowing more about the complex effects of fungicides and other pesticides on bees can help us to create more nuanced recommendations for growers and beekeepers. Read the full study.

Establishing baseline national information on in-hive pesticides will allow us to detect future trends, and can inform recommendations for growers and beekeepers. The results from this study are consistent with other pollen pesticide surveys, including one conducted in MA in 2018 (read about it at https://ag.umass.edu/resources/pollinators/research-projects-at-umass/2018-massachusetts-hobbyist-health-survey). The fact that this study finds a link between fungicides and Nosema is especially interesting because, even though fungicides are not very toxic to bees directly, researchers are beginning to realize that they may impact hive health in significant ways. Knowing more about the complex effects of fungicides and other pesticides on bees can help us to create more nuanced recommendations for growers and beekeepers. Read the full study.

Hannah Whitehead, UMass Extension Honey Bee Educator

Upcoming Events

For more details and registration options for any of these events, go to the UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, and Urban Forestry Program Upcoming Events Page.

-

Aug 31 - Spotted Lanternfly Trapping Update Webinar

Credits: 1 pesticide credit for categories 25, 27, 29, 35, 36, 48 and Applicator's/Core License; 1.5 ISA, 1 (cat 1) SAF, 1 MCH, 1 MCA, and 1 MCLP credits available. -

Sept 22 - Ornamental Tree and Shrub ID & Insect Walk - in person, Berkshire Botanical Garden, Stockbridge MA

Credits: 1 pesticide credit for categories 36 and Applicator's/Core License; 1 MCA, 1 MCLP. and 1 MCH credits available; ISA credit requested. -

Invasive Insect Certification Program - a series of 6 webinars, 9:00 AM – 12:00 PM

Credits: 2 pesticide credits for categories 35, 36, 48 and Applicators License available for EACH webinar.-

Day 1: Tue, Sept 28: The Impacts and Costs of Invasive Insects

-

Day 2: Wed, Sept 29: The Impacts and Costs of Invasive Insects, continued

-

Day 3: Tue, Oct 12: Invasive Forest and Agricultural Insects in MA: Current and Future

-

Day 4: Wed, Oct 13: Invasive Forest and Agricultural Insects in Massachusetts

-

Day 5: Tue, Oct 26: Management of Invasive Forest and Landscape Insect Pests

-

Day 6: Wed, Oct 27: Management of Invasive Forest and Landscape Insect Pests, continued

-

Pesticide Exam Preparation and Recertification Courses

These workshops are currently being offered online. Contact Natalia Clifton at nclifton@umass.edu or go to https://www.umass.edu/pested for more info.

InsectXaminer!

Episodes so far featuring gypsy moth, lily leaf beetle, euonymus caterpillar, and imported willow leaf beetle can be found at: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/insectxaminer

TickTalk with TickReport Webinars

To view recordings of past webinars in this series, go to: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/ticktalk-with-tickreport-webinars

Additional Resources

For detailed reports on growing conditions and pest activity – Check out the Landscape Message

For professional turf managers - Check out our Turf Management Updates

For commercial growers of greenhouse crops and flowers - Check out the New England Greenhouse Update website

For home gardeners and garden retailers - Check out our home lawn and garden resources.

Diagnostic Services

Landscape and Turf Problem Diagnostics - The UMass Plant Diagnostic Lab is accepting plant disease, insect pest and invasive plant/weed samples . By mail is preferred, but clients who would like to hand-deliver samples may do so by leaving them in the bin marked "Diagnostic Lab Samples" near the back door of French Hall (please note that visitors are not allowed inside the building). The lab serves commercial landscape contractors, turf managers, arborists, nurseries and other green industry professionals. It provides woody plant and turf disease analysis, woody plant and turf insect identification, turfgrass identification, weed identification, and offers a report of pest management strategies that are research based, economically sound and environmentally appropriate for the situation. Accurate diagnosis for a turf or landscape problem can often eliminate or reduce the need for pesticide use. See our website for instructions on sample submission and for a sample submission form at https://ag.umass.edu/services/plant-diagnostics-laboratory. Mail delivery services and staffing have been altered due to the pandemic, so please allow for some additional time for samples to arrive at the lab and undergo the diagnostic process.

Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing - The UMass Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Lab is accepting orders for routine soil analysis and particle size analysis ONLY (please do not send orders for other types of analyses at this time). Send orders via USPS, UPS, FedEx or other private carrier (hand delivered orders cannot be accepted at this time). Processing time may be longer than usual since the lab is operating with reduced staff and staggered shifts. The lab provides test results and recommendations that lead to the wise and economical use of soils and soil amendments. For updates and order forms, visit the UMass Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory web site.

Tick Testing - The UMass Center for Agriculture, Food, and the Environment provides a list of potential tick identification and testing options at: https://ag.umass.edu/resources/tick-testing-resources.