A monthly e-newsletter from UMass Extension for landscapers, arborists, and other Green Industry professionals, including monthly tips for home gardeners.

Click on the headings below to jump to that section of the newsletter.

In This Issue

- Disease of the Month: Red Thread on Lawns

- Need to Report an Invasive Insect?

- Q&A - Lawn Topics: Moss, Nitrogen Fertilizer, Annual Ryegrass

- Garden Clippings Tips of the Month

- It’s Tick Season! Well, it’s Always Tick Season...

- Upcoming Events

To print this issue, either press CTRL/CMD + P or right click on the page and choose Print from the pop-up menu.

Disease of the Month: Red Thread on Lawns

Periods of cool, wet weather this spring provided the perfect conditions for red thread on home lawns. Red thread is caused by Laetisaria fuciformis. This fungus overwinters in soil and becomes active in spring. It is dispersed by wind, splashing water, and human activity. It penetrates grass blades through stomata (leaf pores) and through wounds.

Periods of cool, wet weather this spring provided the perfect conditions for red thread on home lawns. Red thread is caused by Laetisaria fuciformis. This fungus overwinters in soil and becomes active in spring. It is dispersed by wind, splashing water, and human activity. It penetrates grass blades through stomata (leaf pores) and through wounds.

Red thread occurs in the cool (60-75°F), wet weather of spring or fall. It is most often seen in the spring before grass growth really takes off. The fungus produces reddish structures on the tips of infected grass blades and dark pink patches appear in lawns. Patches eventually become pale and bleached out, and turf can take on a ragged appearance. Red thread is largely a cosmetic issue - it will not kill turf crowns or roots. All turfgrass species are susceptible, though in general perennial ryegrass and fescues are more severely affected.

Fortunately, red thread is relatively easy to manage. Fungal growth slows significantly when the temperature exceeds 75°F, so this disease will disappear when the summer heat arrives. Red thread is exacerbated by low nitrogen fertility, low soil calcium, water stress, and any other condition that slows turf growth. Ameliorating these conditions is the key to combating the disease.

A light application of up to 0.2 lbs/1000 ft2 of quick release nitrogen in mid- to late spring can help the turf recover. Have a soil test done and ensure that there is adequate calcium, potassium, and phosphorus available. Maintain a soil pH of 6.0-7.0. Ensure that mower blades are sharp to minimize wounding of grass blades. Collection and off-site disposal of clippings may be warranted with severe infestations, if possible. Manage thatch, which serves as a nice place for pathogens to hide out. Cultivars vary in susceptibility; overseed with resistant ones. Fungicides are available but are seldom necessary on home lawns. For more details, see our UMass Extension Red Thread fact sheet.

When summer temperatures are late in coming, the red thread season can seem particularly long. Patience will be rewarded when summer warmth arrives and the turf is able to replace the damaged grass blades with healthy ones.

Angela Madeiras, UMass Extension Plant Pathologist

Trouble Maker of the Month

Need to Report an Invasive Insect?

Did you find a spotted lanternfly, box tree moth, elm zigzag sawfly or Asian longhorned beetle (in any life cycle stage), or suspicious damage to a tree or shrub? Don't know who to contact? We've got you covered...

Spotted lanternfly, box tree moth, elm zigzag sawfly, and Asian longhorned beetle are all present in Massachusetts. Reporting new locations where each of these insects is found is still very important. In Massacusetts, you can report each in the following ways:

- Spotted Lanternfly Report Form

- Box Tree Moth Report Form

- Elm Zigzag Sawfly Report Form

- Asian Longhorned Beetle (ALB) Report Form or call the ALB Eradication Program at 508-852-8090.

If you have observed one of these insects or the damage they cause in a state other than Massachusetts, you can search by your state and find how to report on the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) website.

Not sure what to look for when?

Each of these insects has their own life cycle, periods of activity, and preferred host plants.

This table summarizes some of this information. |

|||||||||

Name |

Host Plants* |

April |

May |

June |

July |

August |

September |

October |

November |

| Spotted lanternfly | Tree of heaven, grape, black walnut, & many others. | Overwintering egg masses. Egg hatch by late April/early May and may last into June. | 1st and 2nd, instar nymphs maturing. | 1st, 2nd, and 3rd instar nymphs maturing depending upon timing of egg hatch. | 4th instar nymphs (black, white, and red) & possibly adults at the end of the month. | 4th instar nymphs (black, white, and red) & adults. | Adults & newly laid egg masses. | Adults killed by frost. Egg masses overwinter. | Egg masses overwinter. |

|

Box tree moth*

*Life cycle in MA is not fully understood. |

Boxwood (Buxus spp.) | Eggs, adults, larvae and pupae may be present. | Eggs, adults, larvae and pupae may be present. | Overwintering generation larvae may still be present. Subsequent generation adults, eggs, and pupae may be present. | Subsequent generation eggs, adults, larvae and pupae may be present. | Subsequent generation eggs, adults, larvae and pupae may be present. | Subsequent generation eggs, adults, larvae and pupae may be present. | Subsequent generation eggs, adults, larvae and pupae may be present. | Overwintering caterpillar life stage present in cocoons protected by webbing on the leaves of host plants. |

|

Elm zigzag sawfly*

*Life cycle in MA is not fully understood. |

Elm (Ulmus spp.) | Adults may emerge by the end of April. | Adults may emerge by the beginning of May, or when temperatures warm and leaves are available. Egg laying takes 1-6 days. | Egg hatch can take 4-8 days and caterpillars feed 15-18 days prior to pupating. | Caterpillars, pupae, and adults of subsequent generations possible. | Caterpillars, pupae, and adults of subsequent generations possible. | Caterpillars, pupae, and adults of subsequent generations possible. | Overwintering pupal life stage in densely walled cocoons often in the leaf litter or nearby soil. | Overwintering pupal life stage in densely walled cocoons often in the leaf litter or nearby soil. |

| Asian longhorned beetle | Maple (Acer spp.), birch, elm, willow, horse chestnut and others. | Overwintered larvae may fully mature in preparation to pupate. In New England, larvae may need to be in trees for 2 years before pupation. | Various instar larvae & pupae within trees. | Various instar larvae & pupae within trees. | Adult emergence by July 1. Perfectly round exit holes that a pencil can fit inside may be present in tree. | Adults may be present & laying eggs. Egg sites will be visible on host plant bark. | Adults may be present but are eventually killed by frost. | Larvae tunnel deep into the wood of their host plants to overwinter. | Larvae tunnel deep into the wood of their host plants to overwinter. Old egg sites, exit holes, and open galleries are still visible in trees. |

*This is an abbreviated list of preferred host plants. See UMass Extension's Professional Insect & Mite Management Guide for Woody Plants for more information.

Early reporting is essential for successful management of these insects! If you find them or the damage they cause, note your exact location (physical address or GPS coordinates), the date of the observation, and take photos! Collect a specimen if it is safe to do so, but take a clear, up-close, and in-focus photo first. This helps in case the insect escapes being caught. Thank you!

Tawny Simisky, UMass Extension Entomologist

Q&A

Q. Moss in the lawn is driving me crazy… what do I do!?

A. Start by checking out our recently revised UMass Extension Moss in Lawns fact sheet.

Q. It’s said that nitrogen is the most important nutrient for turfgrass growth, so the more nitrogen fertilizer a lawn receives in a year, the better… right?

A. Definitely not. While growth of turfgrasses is most responsive to fertilizer nitrogen (N), and N is the nutrient required in the largest amounts by turfgrass plants, N fertilizer should always be applied in the lowest amount needed to sustain an acceptable degree of turf appearance and function. Seek instead to optimize, not maximize, N inputs. The main “whys” are foundational to any turf management program… these are:

N fertilizer has direct and indirect costs: Along with what seems like everything else these days, prices for N fertilizer materials have increased steadily over the last several years. This is especially true for the more desirable, user-friendly, and highly engineered slow release and stabilized N technologies, which most often demand premium prices.

There are additional non-monetary costs associated with transport, handling, and of course application, all of which consume precious time and effort. Furthermore, many manufactured N sources are fossil fuel-based, which can contribute to indirect costs in the way of carbon footprint. Optimizing N inputs, therefore, can reduce overall financial, labor, and environmental burdens.

N has the potential to harm water quality: Nitrogen (along with phosphorus) is a pollutant of concern for both surface and groundwater. Excess N loading can lead to eutrophication in surface water, which can reduce dissolved oxygen, impact wildlife and food populations like fish and shellfish, and lower the overall utility of water bodies. Additionally, high nitrate levels in drinking water supplies and groundwater pose risks to humans, especially infants, and for these reasons the US EPA has set strict limits for N in potable water.

While fertilizer is just one of several sources of N in the environment, reducing N fertilizer inputs to the lowest possible level, along with management to keep N from moving out of plant and soil systems, are important steps for maintaining turf responsibly and protecting valuable water resources.

Excess N can negatively affect plant health and functional capacity: It’s a perfect catch-22… ample N is required for strong turf performance, which in turn can help to mitigate the detrimental loss of N and other pollutants described above. Fertilizer N inputs are also correlated with sought-after performance parameters like vigorous growth, stand density, and deep green color. An interesting thing happens in cool-season turfgrasses in response to N availability, however, in that any surplus N above minimum required levels is allocated to shoot growth, which unfortunately happens at the expense of root growth. The greater the N surplus, the greater the potential imbalance in this shoot:root ratio.

For example, there was a long-term study at UMass that looked at a range of N fertilizer rates from low to very high, and the best initial visual quality was observed at the highest rates. When we dug below the surface (literally), however, it was found that rooting capacity was over 60% less at the highest N rates relative to the lowest rates, which was an indicator of extreme shoot:root imbalance and a very unsustainable condition over the longer term. On top of these broader implications, superfluous shoot growth increases mowing (which is among the costliest turf management inputs), not to mention that this rapid growth is most often composed of succulent, less resilient tissue.

Temporally speaking, maximum N availability is best timed to coincide with periods of peak root activity, which in turn maximizes N capture and utilization and reduces loss potential. This makes spring and late summer the most advantageous times for applications of N fertilizer. Know also that excessive application of readily available N is more likely to acutely and directly injure plant tissues (“burning). This is most common under hot and dry conditions.

For more information on optimizing inputs of N and other nutrients for turf systems, see the Soil and Nutrient Management chapter (chapter 7) of UMass Extension's Lawn and Landscape BMP document. For N fertilizer programming in particular, Table 12 on page 68 of the BMP is especially useful.

Q. I see annual ryegrass included in a lot of turf seed mixes, but I’ve heard that it may not be the best choice. Can you give me the inside scoop?

A. Annual ryegrass shows up in a lot of seed mixes, especially consumer-focused mixes sold at big box stores and “contractor”-type mixes, for two main reasons: it’s cheap, and it germinates faster than any other cool-season grass and grows very aggressively early in the life cycle.

That’s about it for the strengths in our southern New England environment, however. When it comes to turf-forming properties, it lands at the bottom among cool-season turfgrass species. It is coarse-textured, with a very light green color, which does not mix well with darker and finer-bladed Kentucky bluegrass, perennial ryegrass, fine leaf fescues, or even many of the turf-type tall fescues. It has a very upright, bunch-type, non-spreading growth habit, which is not conducive to good stand density. It tends to be unbecomingly stemmy during certain times of the year. Annual ryegrass is also short-lived and intolerant of temperature extremes.

While annual ryegrass is an important forage grass, and it does retain some utility in southern growing environments for winter overseeding of warm season turf surfaces, its usefulness as a turfgrass in this region is very limited. One of the primary reasons is that perennial ryegrass also exists. Perennial ryegrass shares some of the same principal positive attributes with annual ryegrass, most notably quick germination and aggressive establishment, while also possessing numerous additional desirable characteristics. These include traits like darker green color, fine leaf texture, and superior wear tolerance. Furthermore, there is an extensive and long-term breeding effort around perennial ryegrass, which means hundreds of commercial varieties that can be selected for needs ranging from better performance in shaded environments to salt tolerance. The higher cost per pound for perennial ryegrass is not likely to be a deal breaker in many instances, and even a modest perennial ryegrass cultivar is likely to perform much better relative to the best annual ryegrass.

One used to hear more about annual ryegrass with regard to “nurse grass” applications… meaning that it would be included in a mix to come up fast, hold the soil, and establish a stand prior to fading away and allowing the other, slower species in the mix to fill in later. The reality often was, however, that the aggressive growth of the annual ryegrass would crowd out the other species early, permanently affecting stand percentages and persistence. It’s usually better to choose perennial ryegrass with the intention for it to be a permanent stand component, while carefully considering species proportions in a mix. Other tools like mulches, seeding techniques, and establishment timing can all also be used to mitigate the need for a nurse grass.

If there is a very specific demand, such as a cover crop to hold a stockpiled mound of topsoil for a year, or a temporary lawn to hold a surface together for the summer before a permanent lawn can be established later in the season, then annual ryegrass may be a viable solution. Otherwise, avoid the annual ryegrass… a modern perennial ryegrass is going to be a superior choice in the vast majority of cases.

Jason D. Lanier, UMass Extension Turf Specialist

Garden Clippings Tips of the Month

May is the month to . . . .

-

Set tomato (as well as eggplant, pepper, cucumber, squash, and melon) transplants in the garden when soil has warmed to around 60ºF and the danger of frost has passed. If possible, transplant on a cloudy day just before a rain shower. Spindly tomato plants may be planted deep since they are able to form roots all along their stems.

-

Harvest rhubarb stems by pulling, not cutting. Cutting leaves a portion of stem behind that can permit disease-causing fungi to enter the plant. When harvesting, try not to remove more than a third of the stems on a single plant. It’s asparagus season, too. Harvest asparagus when stalks are 6 to 10 inches in height and before the heads begin to open. As tempting as it may be, refrain from harvesting asparagus from beds that are less than 2 years old. When harvesting, cut or snap off spears at ground level. Do not leave aboveground stubs as these may attract asparagus beetles or serve as entry points for disease.

-

Make the first sowings of green beans. Continue to make successive sowings of bush-type beans at two-week intervals into early July. A single sowing of pole beans near Memorial Day will provide a continuous supply of beans from late July until frost.

-

Apply an organic mulch (such as wood chips, compost, or bark) around newly planted trees. However, avoid creating “mulch volcanoes.” A mulch volcano is a high mound of mulch piled as much as 10 or more inches against the trunk of a tree. It may take a few years, but eventually a mulch volcano will cause serious and often fatal damage to the tree trunk. Keep mulch depth 3 inches or less and never pile it against a tree trunk.

-

Stay on top of weeding. Shave off weeds with a sharp garden hoe when they reach a height of no more than 2 inches. Use the hoe in a gliding motion (as if sweeping with a push broom or sponge mopping) rather than a chopping or digging motion, and change hand positions frequently to reduce repetitive motion fatigue.

-

Install hoops around peonies and other tall perennials that tend to flop. It is easier to position hoops and stakes while plants are small — there is less vegetation to work around and less chance of damaging flowers and stems.

-

Plant gladiolus corms. Stagger the planting: several corms planted every 2 weeks from early May until mid-June will provide cut flowers from July to early September. Set corms 4 to 6 inches deep and 3 inches apart in a prepared garden bed. Mid- to late May is also a good time to plant dahlia tubers outside. Plant tubers horizontally at a depth of 6 inches and space them about 18 inches apart if growing multiple dahlias in a cutting garden or set them at least 18 inches from other perennials if growing individual dahlias in a landscape bed.

-

Hold off on watering lawns until there is a long stretch of dry weather. There is usually plenty of soil moisture at this point in the season. Watering lawns now will discourage deep root growth and may promote disease development.

-

Check the surface soil of potted plants. Soils with a high peat moss content can become crusty and shrink when the soil gets too dry. As a result, water applied to the pot won’t penetrate--it runs down the inside walls of the pot without wetting the soil. Break up the crusty surface.

-

Monitor the leaves of bearded iris for signs of iris borer. Look for tan water-soaked streaks on the leaves. These streaks denote tunnels made by the borers as they feed inside the leaves. Squish borers by hand or apply sprays of natural products such as spinosad or beneficial nematodes according to label instructions.

-

Don't forget to get a soil test! May and June are the busiest time of year for the UMass Soil & Plant Nutrient Testing Lab, so beat the rush by submitting soil samples before mid-May. The Routine Soil Analysis tests for pH, major and micro nutrients, lead, and cation exchange capacity and provides crop-specific lime and nutrient recommendations. The lab's website has order forms and info on how to take and send a sample.

Jennifer Kujawski, Horticulturist

It’s Tick Season! Well, it’s always tick season...

Spring is finally upon us and it always raises the question to me from the general public and the media: “Larry, is tick season about to start?” And given the mild winter, "Is it going to be a bad tick year?"

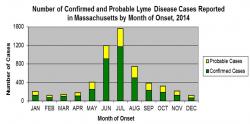

The fact is that tick season never ended…it just moves into different phases. The chart below shows there are cases of Lyme disease every month. Whenever temperatures are above freezing and there is no snow cover, ticks are more than capable of attaching to you or a pet. Ticks manufacture the chemical glycerol, which is basically antifreeze. As to this year's mild winter, also no impact on tick populations. A number of predictions have appeared in the media which would lead one to think the tick apocalypse is imminent. The size of the tick population this year is based on the size of the acorn crop two years ago. Check out a Cape Cod Cooperative Extension video I made on how this ecosystem works.

So where are we right now? From here on out until August, it is the nymph stage of deer ticks that are active. While you may get a tick bite any month of the year, the tick's nymph stage accounts for 85% of all tick borne disease infections, which includes Lyme, Babesiosis, and Anaplasmosis. The key reason is that nymph stage ticks are the size of a poppy seed and can more likely elude even a careful tick check.

So where are we right now? From here on out until August, it is the nymph stage of deer ticks that are active. While you may get a tick bite any month of the year, the tick's nymph stage accounts for 85% of all tick borne disease infections, which includes Lyme, Babesiosis, and Anaplasmosis. The key reason is that nymph stage ticks are the size of a poppy seed and can more likely elude even a careful tick check.

So, remember to observe the basics of personal protection. First and foremost, this includes regular tick checks, tossing clothes in the dryer for 20 minutes, and treating clothing and footwear with permethrin, the most effective tool in the box for preventing tick bites. In the event you do get a tick bite, prompt removal is key and consider getting the tick tested. UMass Extension provides a list of potential tick identification and testing options.

Larry Dapsis, Entomologist, Cape Cod Cooperative Extension (retired)

Upcoming Events

For details and registration options for these upcoming events, go to the UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, and Urban Forestry Program Upcoming Events Page.

-

June 4 - Conifer Diseases Walk, Arnold Arboretum, Jamaica Plain MA, 5:00 to 7:00 pm. 2 pesticide contact hours available for categories 29, 35, 36, and Applicators License. Association credits: 1 MCA, 1 MCLP, 1 MCH. ISA, SAF, and CFE requested.

Additional Resources

For detailed reports on growing conditions and pest activity – Check out the Landscape Message

For professional turf managers - Check out our Turf Management Updates

For commercial growers of greenhouse crops and flowers - Check out the New England Greenhouse Update website

For home gardeners and garden retailers - Check out our home lawn and garden resources

TickTalk webinars - To view recordings of past webinars in this series, go to: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/ticktalk-with-tickreport-webinars

Diagnostic Services

Landscape and Turf Problem Diagnostics - The UMass Plant Diagnostic Lab is accepting plant disease, insect pest and invasive plant/weed samples. By mail is preferred, but clients who would like to hand-deliver samples may do so by leaving them in the bin marked "Diagnostic Lab Samples" near the back door of French Hall. The lab serves commercial landscape contractors, turf managers, arborists, nurseries and other green industry professionals. It provides woody plant and turf disease analysis, woody plant and turf insect identification, turfgrass identification, weed identification, and offers a report of pest management strategies that are research based, economically sound and environmentally appropriate for the situation. Accurate diagnosis for a turf or landscape problem can often eliminate or reduce the need for pesticide use. See our website for instructions on sample submission and for a sample submission form at http://ag.umass.edu/diagnostics.

Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing - The lab is accepting orders for Routine Soil Analysis (including optional Organic Matter, Soluble Salts, and Nitrate testing), Particle Size Analysis, Pre-Sidedress Nitrate (PSNT), Total Sorbed Metals, and Soilless Media (no other types of soil analyses available at this time). Testing services are available to all. The lab provides test results and recommendations that lead to the wise and economical use of soils and soil amendments. For updates and order forms, visit the UMass Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory web site.

Tick Testing - The UMass Center for Agriculture, Food, and the Environment provides a list of potential tick identification and testing options at: https://ag.umass.edu/resources/tick-testing-resources.