A monthly e-newsletter from UMass Extension for landscapers, arborists, and other Green Industry professionals, including monthly tips for home gardeners.

To read individual sections of the message, click on the section headings below to expand the content:

Fall Wrap-Up for Woody Ornamentals and Turf in December

Join us via GoToWebinar for a review of the challenges and problems of the 2020 season. Attendees can choose to attend either the landscape topics session on December 2 or the turf topics session on December 4, or the entire two-day program. Both will be held as live webinars from 8:30 am to 12:00 pm, with three topics on each day.

Join us via GoToWebinar for a review of the challenges and problems of the 2020 season. Attendees can choose to attend either the landscape topics session on December 2 or the turf topics session on December 4, or the entire two-day program. Both will be held as live webinars from 8:30 am to 12:00 pm, with three topics on each day.

Woody Ornamentals topics in the half-day session on Dec. 2 include: Review of Pests and Diseases; Year in Review of Troublesome Insect and Mite Pests of Woody Plants; and Four Difficult-to-Manage Landscape Weeds.

Turf topics in the half-day session on Dec. 4 include: A Tough Year for Turf: Lawn Health Issues Observed in the UMass Plant Diagnostic Lab; Five Difficult-to-Manage Turf Weeds; and The Turf Entomologist’s Season in Review.

CREDITS

- Dec. 2 Session ONLY: 3 pesticide contact hours for categories 29, 36 , Dealer, or Applicators License. Association credits: 2 ISA, 1 MCA, 1 MCLP, and 1 MCH

- Dec. 4 Session ONLY: 3 pesticide contact hours for categories 37, Dealer, or Applicators License. Association credits: 1 MCH and 1 MCLP

- BOTH DAYS: 6 for Dealer and Applicators License; 3 pesticide contact hours for categories 29, 36, or 37. Association credits: 2 ISA, 1 MCA, 2 MCLP, and 2 MCH

For more details, the full schedule, and registration info, go to: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/events/fall-wrap-up-landscape-woody-ornamental-122-or-turf-124-topics

2021 UMass Garden Calendar

For many years, UMass Extension has worked with the citizens of Massachusetts to help them make sound choices about growing, planting and maintaining plants in their landscapes, including vegetables, backyard fruits, and ornamental plants. Our 2021 Garden Calendar continues UMass Extension’s tradition of providing gardeners with useful information. This year’s calendar offers tips on getting started with a vegetable garden with an emphasis on the basics, raised beds, and growing in containers. Many people also love the daily tips and find the daily sunrise/sunset times highly useful!

For many years, UMass Extension has worked with the citizens of Massachusetts to help them make sound choices about growing, planting and maintaining plants in their landscapes, including vegetables, backyard fruits, and ornamental plants. Our 2021 Garden Calendar continues UMass Extension’s tradition of providing gardeners with useful information. This year’s calendar offers tips on getting started with a vegetable garden with an emphasis on the basics, raised beds, and growing in containers. Many people also love the daily tips and find the daily sunrise/sunset times highly useful!

Show your clients you appreciate their business this year! Bulk pricing is available on orders of 10 copies or more (single copy price: $14/ea).

FOR IMAGES IN THE CALENDAR, details, and ordering info, go to umassgardencalendar.org.

As always, each month features:

- An inspiring garden image.

- Daily gardening tips for Northeast growing conditions.

- Daily sunrise and sunset times.

- Phases of the moon.

- Plenty of room for notes.

- Low gloss paper for easy writing.

Featured Plant

Honshu maple (Acer rufinerve 'Winter Gold')

As we slip into the dormant season and the landscape around us becomes shades of tan, brown, gray and white, each spot of color becomes increasingly important. Strategically placing plants to bring a spark of color to the winter landscape is a brilliant way to connect with nature even from the comfort of indoors.

Many wonderful trees and shrubs with berries, evergreen foliage, and colorful bark including winterberry, red-stemmed dogwoods and willows, paperbark maple and birch are commonly available and are becoming more widely used. When judiciously placed, their varied shape and form bring color to the landscape from late autumn right into early spring, giving a place for the human eye to rest and enjoy while simultaneously providing cover and food for birds.

A wonderful addition to the winter scene, though little-known, is a beautiful cultivar of the Honshu maple (Acer rufinerve) called ‘Winter Gold’. In addition to adding pizzaz to the winter scene, this tree is well suited to modern landscapes because of its size, hardiness and adaptability.

The species occurs in forests in the mountains of Japan, populating forest gaps and edges, residing comfortably in the partial shade of larger trees. Like our native moosewood maple (Acer pensylvanicum), to whom it is related, it is happiest in the garden given protection from hot midday sun and searing winds, and thrives in humus-rich garden soil which is evenly moist. When happy it will reach 30’ to 35’ tall and perhaps 20’ wide. While commonly known as a snake-bark or striped maple, I rather prefer the common name which is translated from the Japanese ‘urihadakaede’ to melon-skin maple. This name more closely describes the network of lenticels and diamond-shaped bark marking which punctuate the green-gray trunk of the species. In the case of the cultivar ‘Winter Gold’, the trunk is a striking yellow which shows dramatically against evergreen or dark backgrounds.

The three-lobed leaves, which are 3-6“ long and wide, are said to turn enticing shades of yellow, orange and red in fall. My own specimen turns a deep, satisfying buttery yellow. As the leaves drop and cold weather sets in, young stems and twigs deepen from gold to vibrant coral. Caught in the late day sun, the twigs appear to glow. The buds, containing the promise of leaf and flower for next year, are blushed in pink and overlaid with bluish bloom.

This cultivar is a bit hard to find and tricky to propagate but worth seeking out for the relief it brings to the winter scene.

Joann Vieira, Director of Horticulture, The Trustees of Reservations

Questions & Answers

Q. How can I balance fall clean-up with preservation of overwintering sites for pollinators and beneficial insects?

A. This is a complicated question, but in general there are a few simple actions you can take to provide overwintering refuges for pollinators and beneficial insects, along with food sources for other wildlife. You will want to balance this, however, with fall clean-up actions that can help reduce pest insect populations, thus helping to reduce the need for potential chemical management options in the future. (For example, if you have a pest on a plant that overwinters as an adult in the leaf-litter beneath the host plant, that would be an example of an area where you would selectively remove that leaf-litter for the benefit of reducing the pest population.)

Broadly speaking, if there are “unkempt” areas in your landscape that you can leave that way – leaving behind dropped fall foliage, broken/fallen branches, even dropped logs – this can be very helpful for overwintering beneficial insects and pollinators. Leaving things in a natural state, is not only easier (less work for you), but also provides an overwintering location for beneficial insects. An exception to this would be areas where these actions could promote pest insects and diseases or could become hazardous (using the example of standing dead trees – these are great habitats for wildlife, but not great if they could be hazardous to people, buildings, vehicles, etc.).

Resisting the urge to cut back dead flowers, especially sunflowers (Helianthus spp.), asters (Symphyotrichum spp.), goldenrod (Solidago spp.), coneflowers (Echinacea spp.), blazing stars (Liatris spp.), and Joe Pye weed (Eupatorium spp.), can also provide an overwintering seed source for birds and other wildlife. This also sets you up to prune these stems next spring, and if done properly that will create enticing nesting sites (hollow and exposed stems) for some of our native, stem-nesting bees. A nice resource for more information regarding pollinator habitat and biology is the USDA NRCS’s New England Pollinator Handbook, which can be found at: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcs142p2_010204.pdf

Q. Is late October - early November too late to treat a tree or a shrub for an insect infestation with systemic insecticides?

A. This is another complicated question. It depends on what the insect is, and what active ingredient you are using, the method of application, environmental conditions at that location, and sometimes even the host plant. In general, systemic insecticide applications work best when soil conditions are favorable for translocation into the foliage (high relative humidity with soil temperatures above 41°F, roughly, and with adequate moisture). It is also important to consider when the damaging life stage of the insect will be active and feeding and coming into contact with the insecticide. Using the invasive emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis; EAB) as an example, sometimes infestations of EAB in ash (Fraxinus spp.) trees are not noticed until the fall. Research has shown that it is possible to get some benefit from a systemic insecticide treatment in the fall, but perhaps not as much benefit as from a spring application. For example, when the active ingredient emamectin benzoate is injected in September, enough insecticide was found in the canopy the following spring to kill leaf-feeding adults and young larvae the following summer. Imidacloprid applied to ash trees between early October and early November was shown to generally manage EAB the next summer, but a large field study showed that over time, fall applications of systemic insecticides to manage EAB did not protect ash trees as effectively as spring applications of the same products. For more information specific to managing the emerald ash borer, visit this site.

If a particularly harmful pest insect is detected in the late fall and it is determined that chemical management options may be necessary at that specific site or location, it may be most helpful to make records of that detection and begin a conversation with the property owner about a monitoring and potential management plan for the spring. But again, this is a tough and complicated question, and depends on the details of the specific scenario.

Tawny Simisky, Extension Entomologist, UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, & Urban Forestry Program

Trouble Maker of the Month

Deep-Rooted Oak Woes: Stem and Branch Cankering from Botryosphaeria and Diplodia

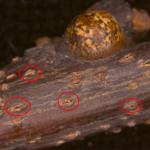

Landscape and urban oaks (Quercus spp.) continue to suffer from stem and branch cankering infections, caused by various species of Botryosphaeria and Diplodia. These fungal pathogens are found worldwide and some have very broad host ranges among woody plants. Many of the affected oaks have been predisposed to attack, weakened by drought, insect defoliation, and scale infestation. Since 2015, there has been a cascading sequence of stress events that continues to materialize today. The dry conditions of 2015 and the severe drought of 2016 created their own unique stress. But more importantly, the drought fueled the massive gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar) outbreak by suppressing the fungal and viral pathogens that often contain this non-native pest. While gypsy moth populations peaked in 2017, when over 900,000 acres in Massachusetts experienced defoliation, the stress drove a surge in secondary pest and pathogen activity that we are still dealing with today. Two-lined chestnut borer and Armillaria root rot are two well-known examples. In 2018, outbreaks of the oak lecanium scale (Parthenolecanium quercifex) were documented in areas where trees were badly weakened by defoliation (Oak lecanium scale was previously discussed in Hort Notes here). Like all scale insects, the oak lecanium scale uses its piercing and sucking mouthparts to extract fluids from small stems and branches. These feeding wounds can be subsequently colonized by stem cankering pathogens like Botryosphaeria and Diplodia. However, any number of minor to major wounds can serve as entry points for these fungi, especially on trees weakened by drought and defoliation.

Once established, Botryosphaeria and Diplodia create numerous small cankers as they consume sugars within the cambium and outer sapwood. These cankers expand to girdle stems and branches, resulting in a sporadic dieback of the canopy. Symptoms of infection can be highly variable and may include sunken or sap-stained lesions and splitting or cracking bark with surrounding wound wood. Conversely, there may be no symptoms of infection at all on stems and branches, aside from browning leaves that are starved of water. However, shaving the outer bark on infected stems will often reveal a brown to black discoloration of the vascular tissue. At times, very small, black-colored fruiting bodies (pycnidia) may also be observed rupturing through the bark on infected stems.

Recent studies continue to reveal a high diversity of Botryosphaeria and Diplodia species attacking oaks in the region. Two species are of particular concern, D. corticola and D. quercivora, as both have been associated with oak declines in North America and Europe over several decades. Recently, D. corticola was found causing serious branch and trunk cankers on black oaks (Q. velutina) weakened by the black oak cynipid gall wasp (Zapatella davisae) outbreak on the Cape and Martha’s Vineyard. However, many other species can be found on oaks in the northeast, such as B. dothidea, B. stevensii, B. quercuum and even D. sapinea, which is primarily a needle and shoot blight pathogen of hard pines.

While field identification of Botryosphaeria and Diplodia can be challenging, successful management is even more difficult. An important point to consider is that for many trees, multiple predisposing stresses have facilitated disease development. Without any amelioration of those stresses, active management of cankering fungi will likely produce few results. For large and mature oaks, pruning and removal of dead stems and small branches can be a daunting to impossible task, given the number of blighted canopy parts. However, pruning of diseased material is an important step in reducing the inoculum capable of infecting healthy tissue. Injection with a systemic fungicide like propiconazole (AlamoTM) may also help to slow the progression of disease, especially when other stresses are present. Air spading can be performed to address soil compaction and to establish or widen mulch rings to limit competition with moisture-sucking turfgrasses. Fertilization, soil amendment with compost or other materials (e.g. biochar), and supplemental watering (if possible or practical) may also help to improve tree vigor. While some trees may have been on the slow road to recovery, the 2020 drought has dealt a significant blow to their renewal. Overall, this current situation has been a bitter reminder that stress events from previous years can continue to manifest, working to weaken our indispensable landscape and urban trees.

Nicholas J. Brazee, UMass Extenstion Plant Pathologist

Garden Clippings Tips of the Month

November is the time to:

- Finish fall cleanup. As mentioned in the Q&A, it is important to balance supporting pollinators and wildlife while also thinking of the overall performance of the landscape. Keep in mind that diseases and insects can survive through the winter on infected plant materials. Any plant material known to have been, or was suscpeted to have been, infected should be removed and destroyed to prevent further spread.

- Pot up indoor winter bulbs such as amaryllis and paper whites. Most amaryllis bloom 6-8 weeks after planting, but some can take up to 10 weeks, so be sure to check for your cultivar. Paperwhites on the other hand only take 1-2 weeks to bloom after planting. Offsetting planting of bulbs can allow blooming throughout the winter.

- Troubleshoot Christmas (or Thanksgiving) cactus problems. Both types of cactus are short day plants, requiring 6 weeks of short days (long nights) in order to bloom. Plants that turn purplish may be experiencing too much sun, phosphorus deficiency, or too little water. Plants are best placed where they receive bright light but not direct sunlight. Plants are generally disease free unless overwatered. Curious if you have a Thanksgiving or Christmas cactus? The difference between them can be found in the shape of the leaves. Thanksgiving cactus (Schlumbergera truncata) has leaves with very pointed and claw shaped projections on the edges of the leaves while Christmas cactus (Schlumbergera bridgesii) has leaf projections that are more scalloped or tear drop shaped.

- Decorate outside containers with holiday decorations. Spruce, fir, arborvitae, winterberry holly, red twig dogwoods, and holly are a festive additional to holiday décor. You can create wreaths, swags, or kissing balls. Alternatively, add the greenery to outdoor containers or hanging baskets.

- Make sure evergreens are watered. Winter desiccation injury can be a common problem for evergreens (especially broadleaved evergreens) in New England. Evergreens are still transpiring but often can’t take up more water because the ground is frozen. Keeping plants well watered up to the time the soil freezes can help prevent winter desiccation injury.

- Put in place evergreen winter protection if needed. Plants close to the roofline may need to be protected from snow falling off the roof that could result in broken stems. Structures can be used to prevent snow from falling on these plants. When using burlap to protect evergreens from harsh winter winds, be sure to not wrap the plants too tightly. A preferred method is to create a wall using stakes and burlap that is not directly touching the plants; this allows for air circulation and helps prevent foliar disease.

- Make notes for spring. Now is a great time to decide what worked well and what didn’t. Make a plan for transplanting, dividing, and new projects.

- Check your local garden center for gardening and landscape gifts!

Mandy Bayer, Extension Assistant Professor of Sustainable Landscape Horticulture

What We Learned From our Interviews with Massachusetts’ Tree Wardens

Several years ago we described a new initiative (Citizen Forester, Dec 2013) from the Urban Forestry Extension Program here at UMass, that was designed to gather information about the state of our urban forests in Massachusetts and better understand the day-to-day challenges, needs, and dynamics of urban forestry at the community level. Though a number of approaches were initially explored, such as focus groups or mail-based surveys, it was ultimately decided that we would employ qualitative research interviews (Elmendorf & Luloff, 2007; Gillies et al., 2014; Diehl et al., 2017) with tree wardens, as it was believed that this approach would:

- Foster two-way communication and build rapport (Creswell, 2007)

- Facilitate the building of knowledge of urban forestry issues in Massachusetts

- Inform the creation of relevant urban forestry Extension programming opportunities.

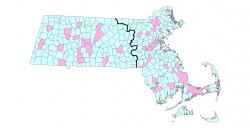

From 2013-2016, we conducted fifty in-person interviews of active tree wardens (Harper et al. 2017) throughout Massachusetts (Fig.1). Interviews themselves typically took 15-30 mins each to complete, and they also routinely involved an extensive post-interview tour of the municipality where noteworthy urban trees, parks, and green spaces were explored. In part I of this two-part series, we commence describing the findings from these interviews.

From 2013-2016, we conducted fifty in-person interviews of active tree wardens (Harper et al. 2017) throughout Massachusetts (Fig.1). Interviews themselves typically took 15-30 mins each to complete, and they also routinely involved an extensive post-interview tour of the municipality where noteworthy urban trees, parks, and green spaces were explored. In part I of this two-part series, we commence describing the findings from these interviews.

A History of Tree Wardens

As many of us recall, tree wardens were established in the U.S. by the Massachusetts (MA) legislature in 1896 (Ricard & Dreyer, 2005), where eventually every community was mandated to employ such an individual (Rines et al., 2010). Presently, this position remains unique to the six states – Rhode Island, Connecticut, MA, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine – that comprise the New England region (Ricard & Bloniarz, 2006).

Tree wardens are most appropriately identified as local officers with the “greatest responsibility” for the preservation and stewardship of public trees in municipalities (Ricard, 2005b) of MA, and other New England states (Ricard, 2005a). According to Ricard and Dreyer (2005) the “…municipal tree warden is arguably the most important human component of a city or town’s community forestry program.” A municipality “cannot conduct an effective community forestry program without the participation, perhaps even the leadership, of a well-qualified, active tree warden.”

What We Learned…

i. The position of Tree Warden.

A majority of the 50 interviewees (n=26), reported that the position of tree warden was located in, or directly affiliated with, the ‘department of public works (DPW).’ A substantial number of interviewees (n=8) also indicated that the position of tree warden was associated with the local ‘highway department’. These themes were consistent with other literature (Ricard and Bloniarz 2006), that reported that New England tree wardens are commonly housed in DPW (44%) and highway departments (15%). Tree wardens that we interviewed often noted associating the terms ‘director’ (n=13) or ‘superintendent’ (n=11) with their position.

ii. The resources available (staff, technical equipment, etc.) to do the job.

A clear majority of the 50 interviewees (n=34) indicated access to occupational resources that facilitated the day-to-day duties of a tree warden, including ‘chipper(s)’ (n=21), a ‘tree crew’ of 2-4 individuals (n=28), and a variety of ‘trucks’ (n=22). A comparison of community sizes (pop 0-10,000, 10,001-20,000 and 20,001-30,000) revealed an increase in the number of tree wardens who identified that these resources were available, as municipal population levels increased. Not surprisingly, a direct relationship between increasing community size and available funds for urban forest management is consistent with findings of other studies (Treiman & Gartner, 2004; Rines et al., 2010; Grado et al., 2013), and may be due to a combination of factors including an increased tax base (Miller & Bates, 1978), increased awareness of the practice of urban forestry among residents (Grado et al., 2013) and the affiliated benefits of urban trees. It may also be associated with a general trend towards greater demand for public services and the level at which they are delivered to residents (Treiman & Gartner, 2005) in more populous communities.

iii. The groups (i.e. organizations, municipal departments) that Tree Wardens routinely interact with, regarding tree-related issues.

A clear majority (n=37) of tree wardens identified local organizations they worked with. These included informal ‘community organizations’ (n=19) comprised of residents like local ‘shade tree committees’ (n=13), ‘garden clubs’ (n=6), ‘conservation groups’ (n=9), or more traditional organizations like ‘municipal departments’ (n=29), including the ‘DPW’ (n=7), ‘highway department’ (n=9), ‘water department’ (n=8), ‘parks department’ (n=5), ‘planning board’ (n=8), and local (i.e., conservation; historical; cemetery; open-space) ‘commissions’ (n=13). Tree wardens in eastern MA more emphatically identified ‘community organizations’ or ‘municipal departments’ than their counterparts in the central-western portion of the state. This would align with findings from other studies since citizens in larger, more populated communities (which are more common in eastern MA) tend to be more active and organized around environmental issues like urban green spaces and trees (Treiman & Gartner, 2005), and feature a higher occurrence of advocacy groups (Rines et al., 2011).

iv. Monitoring for pests.

Nearly every tree warden interviewed indicated that ‘yes’ (n=49), they monitor by at least periodically visually inspecting urban trees for pests. This included Asian longhorned beetle (Anaplophora glabripennis Motschulsky) (n=31), emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire) (n=29), hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae Annand) (n=17), winter moth (Operophtera brumata L.) (n=15), gypsy moth (Lymantra dispar L.) (n=6), Dutch elm disease (Ophiostoma novo-ulmi Brasier) (n=4). Some insect pests were identified in relative equal frequency between tree wardens in eastern MA and central-western MA like Asian longhorned beetle (ALB) and emerald ash borer (EAB).

The high level of responses from the interviewees affirming that they monitor for urban forest pests was of interest, as there is a dearth of information concerning pest-related activities. According to the tree warden from the Town of Wrentham: “we used to have a full-time tree crew and a bigger budget when we were dealing with Dutch elm disease in the 1970s.”

It would seem that urban forest pest issues affected not only resources ascribed to the community tree budget, but also impacted the daily duties of municipal forestry staff, as individuals were presumably dedicated to the full-time removal of large numbers of trees that succumbed to pests like the aforementioned Dutch elm disease (DED), in at least some MA communities. Currently, ash (Fraxinus spp.) comprise 5% of the urban street tree populations in MA (Cummins et al., 2006), but with the relatively recent discovery of EAB, an abundance of biomass will likely continue to be locally generated in communities as these trees die. Hence the subject of urban forest health and its impact on tree warden activities is timely and worthy of further examination. In the next edition of Citizen Forester, we will outline what the interviewees reported about their educational and training needs.

Literature Cited

Creswell, J.W. (2007). (2nd ed.). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among 5 approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Cumming, A. B., Twardus, D. B., & Smith, W. D. (2006). Maryland and Massachusetts street tree monitoring pilot projects. NA-FR-01-06. Newtown Square, PA: USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry.

Diehl, N.W., Sloan, N.L., Garcia, E.P., Galindo-Gonzalez, S., Dourte, D.R., & Fraisse, C.W. (2017). Climate-related risks and management issues facing agriculture in the southeast: Interviews with Extension professionals. Journal of Extension, 55(1), Article 1FEA2. Available at: https://www.joe.org/joe/2017february/a2.php

Elmendorf, W., & Luloff, A. E. (2007). Using key informant interviews to better understand open space conservation in a developing watershed. Arboriculture & Urban Forestry, 32, 54–61.

Gillies, K., Skea, Z.C., & Campbell, M.K. (2014). Decision aids for randomized controlled trials: a qualitative exploration of stakeholders’ views. BMJ 4: 1-13.

Grado, S.C., Measells, M.K., & Grebner, D.L. (2013). Revisiting the status, needs and knowledge levels of Mississippi’s Governmental Entities relative to urban forestry. Arboriculture and Urban Forestry 39(4): 149-156.

Harper, R.W., Bloniarz, D.V., DeStefano, S., Nicolson, C.R., 2017. Urban forest management in New England: Towards a contemporary understanding of tree wardens in MA communities. Arboricultural Journal 39(3): 1-17.

Miller, R.W., & Bates, T.R. (1978). National implications of an urban forestry survey in Wisconsin. Journal of Arboriculture 4(6): 125-127.

Ricard, R.M. (2005a). Shade trees and tree wardens: Revising the history of urban forestry. Northern Journal of Forestry 103(5): 230-233.

Ricard, R.M. (2005b). Connecticut’s tree wardens: a survey of current practices, continuing education, and voluntary certification. Northern Journal of Applied Forestry 22(4): 248-253.

Ricard, R.M. & Dreyer, G.D. (2005). Greening Connecticut cities and towns: Managing public trees and community forests. University of Connecticut, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources (p. 265). Storrs, CT

Ricard, R. M., & Bloniarz, D. V. (2006). Learning preferences, job satisfaction, community interactions, and urban forestry practices of New England (USA) tree wardens. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, 5, 1–15.

Rines, D.R., Kane, B., Kittredge, D.B., Ryan, H.D.P., & Butler, B. (2011). Measuring urban forestry performance and demographic associations in MA, USA. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 10(2): 113-118.

Rines, D.R., Kane, B., Ryan, H.D.P., & Kittredge, D.B. (2010). Urban forestry priorities of MA (U.S.A.) tree wardens. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 9(4): 295–301.

Treiman T., & Gartner, J. (2005). What do people want from their community forests? Results of a public attitude survey in Missouri, U.S. Journal of Arboriculture 31(5): 243-250.

Treiman T., & Gartner, J. (2004). Community forestry in Missouri, U.S.: attitudes and knowledge of local officials. Journal of Arboriculture 30(4): 205-213.

Rick Harper, Stephen DeStefano, Craig Nicolson, and Emily Huff, Dept. of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts Amherst; Michael Davidsohn, Department of Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning, University of Massachuetts Amherst

Upcoming Events

For more details for any of these events, go to the UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, and Urban Forestry Program Upcoming Events Page.

-

Dec 2 - Fall Wrap-Up for Landscapers

Live webinar - details coming soon! -

Dec 4 - Fall Wrap-Up for Turf Managers

Live webinar - details coming soon!

Tune in to a TickTalk with TickReport Webinars

This is a FREE live webinar series by Dr. Stephen Rich, Director of the UMass Laboratory of Medical Zoology held noon to 1:00 pm on the 2nd Wednesday of the month. Co-sponsored by UMass Extension and the UMass Laboratory of Medical Zoology. Register at https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/webinars

- Dec 9 - More Ticks in More Places; A conversation with Dr. Tom Mather aka “The Tick Guy”

Speaker: Dr. Tom Mather, TickEncounter

The final TickTalk of 2020 will feature a conversation between host Dr. Stephen Rich and his guest Dr. Tom Mather. Dr. Mather will talk about “More Ticks in More Places”, and discuss his highly regarded TickEncounter web site and associated resource center. Dr. Mather is a world-renowned tick expert who has also spent more than a decade bringing his expertise into the public conversation. Dr. Mather discusses the challenges of educating the public about ticks and tick-borne disease in an internet-savvy world where competing messages of questionable veracity can be found in abundance. Join Dr. Mather for an online tour of the TickEncounter web site (including TickSpotters), and hear stories of what happens when people are “just wrong enough” in their understanding of ticks and risk of tick-borne disease."

Pesticide Exam Preparation and Recertification Courses

These workshops are currently being offered online. Contact Natalia Clifton at nclifton@umass.edu or go to https://www.umass.edu/pested for more info.

Invasive Insect Webinars

Find recordings of these webinars at https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/invasive-insect-webinars. Topics include the spotted lanternfly, spotted wing drosophila, brown marmorated stink bug, emerald ash borer, gypsy moth, winter moth, and Asian longhorned beetle.

InsectXaminer!

Episodes so far featuring gypsy moth, lily leaf beetle, euonymus caterpillar, and imported willow leaf beetle can be found at: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/insectxaminer

Additional Resources

For detailed reports on growing conditions and pest activity – Check out the Landscape Message

For commercial growers of greenhouse crops and flowers - Check out the New England Greenhouse Update website

For professional turf managers - Check out our Turf Management Updates

For home gardeners and garden retailers - Check out our home lawn and garden resources. UMass Extension also has a Twitter feed that provides timely, daily gardening tips, sunrise and sunset times to home gardeners at twitter.com/UMassGardenClip

Diagnostic Services

Landscape and Turf Problem Diagnostics - The UMass Plant Diagnostic Lab is accepting plant disease, insect pest and invasive plant/weed samples (mail-in only - walk-in samples cannot be accepted). The lab serves commercial landscape contractors, turf managers, arborists, nurseries and other green industry professionals. It provides woody plant and turf disease analysis, woody plant and turf insect identification, turfgrass identification, weed identification, and offers a report of pest management strategies that are research based, economically sound and environmentally appropriate for the situation. Accurate diagnosis for a turf or landscape problem can often eliminate or reduce the need for pesticide use. Please refer to our website for instructions on sample submission and to access the submission form at https://ag.umass.edu/services/plant-diagnostics-laboratory. Mail delivery services and staffing have been altered due to the pandemic, so please allow for some additional time for samples to arrive at the lab and undergo the diagnostic process.

Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing - The UMass Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Lab is accepting orders for routine soil analysis and particle size analysis ONLY (please do not send orders for other types of analyses at this time). Send orders via USPS, UPS, FedEx or other private carrier (hand delivered orders cannot be accepted at this time). Processing time may be longer than usual since the lab is operating with reduced staff and staggered shifts. The lab provides test results and recommendations that lead to the wise and economical use of soils and soil amendments. For updates and order forms, visit the UMass Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory web site.

TickReport Update - The TickReport Risk Assessment & Passive Surveillance Program is open and tick samples can be submitted via https://www.tickreport.com. Please contact TickReport with with tick-related questions and updates on the status of their service.