In Our Spotlight

Projects and Possibilities: 4-H Urban Programs

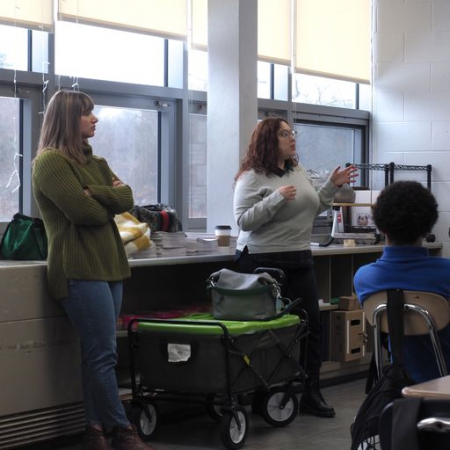

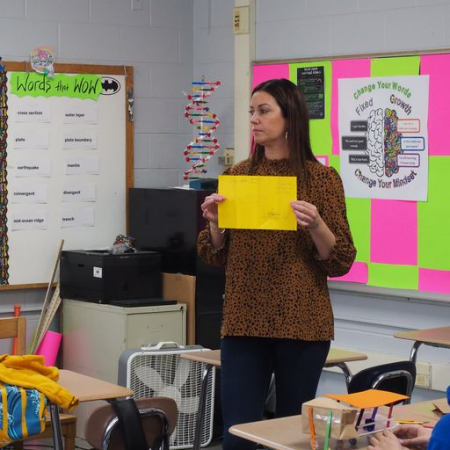

When 4-H comes to science class at Kiley Middle School in Springfield, the traditional model of the teacher talking and students listening takes a back seat. Today, an actual wagon full of mysterious materials catches the attention of a room full of middle school students. Lauren DuBois and Lizmarie Ulloa, 4-H Urban Educators, explain how students will use the contents. Things get hands-on fast as kids pair up to tackle the challenge under the guidance of DuBois, Ulloa, and Kiley Middle School science teacher Brianna Rivers. The assignment requires students to design a device to solve a problem. Then it gets even more interesting…if you can come up with an original idea, maybe you should consider a patent.

full of mysterious materials catches the attention of a room full of middle school students. Lauren DuBois and Lizmarie Ulloa, 4-H Urban Educators, explain how students will use the contents. Things get hands-on fast as kids pair up to tackle the challenge under the guidance of DuBois, Ulloa, and Kiley Middle School science teacher Brianna Rivers. The assignment requires students to design a device to solve a problem. Then it gets even more interesting…if you can come up with an original idea, maybe you should consider a patent.

DuBois and Ulloa share a local example: the paper bag. In the mid-19th century, paper bags were in use, but they were cumbersome and didn’t have flat bottoms. Worse, every bag had to be glued by hand. Springfield’s Margaret Knight figured out how to use a machine to fold and glue flat-bottomed bags. She patented her bag in 1871. It worked so well it’s still in regular use 150 years later

Youth are encouraged to consider past 4-H projects: building bridges, Rube Goldberg machines, water quality testing equipment, a model park, making gummy worms, and extracting iron from cereal.

UMass Extension in Springfield

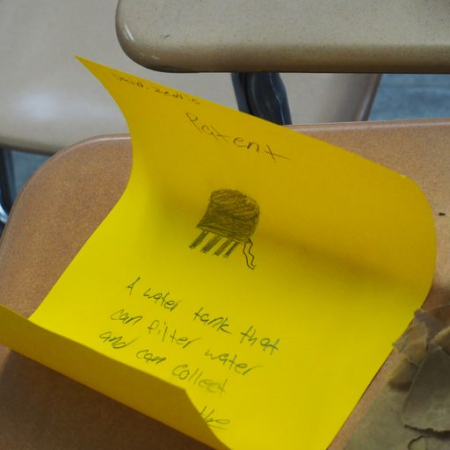

At Kiley Middle School, the 4-H program’s rural roots converge with students’ urban surroundings. Seventh grader Liliana Quintanilla explains she and fellow student Luzciangely Velazquez are creating a water capture-and-storage system for a place that “has a very rainy season and a very dry season, so we need to store water.” Their creation collects rainwater and puts it through a filtration system that holds the clean water.

At Kiley Middle School, the 4-H program’s rural roots converge with students’ urban surroundings. Seventh grader Liliana Quintanilla explains she and fellow student Luzciangely Velazquez are creating a water capture-and-storage system for a place that “has a very rainy season and a very dry season, so we need to store water.” Their creation collects rainwater and puts it through a filtration system that holds the clean water.

The pair say the 4-H program has been fun and they describe their last project, a high-tech trailer designed to withstand extreme heat and acidity of the Venusian atmosphere.

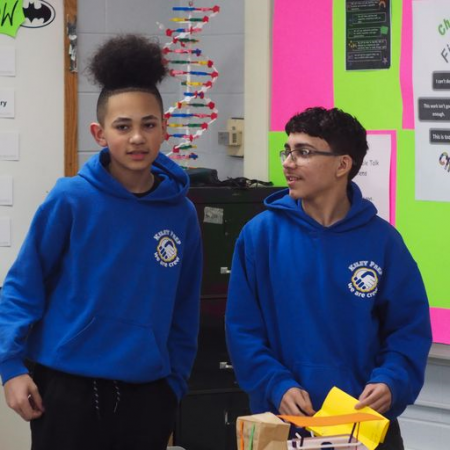

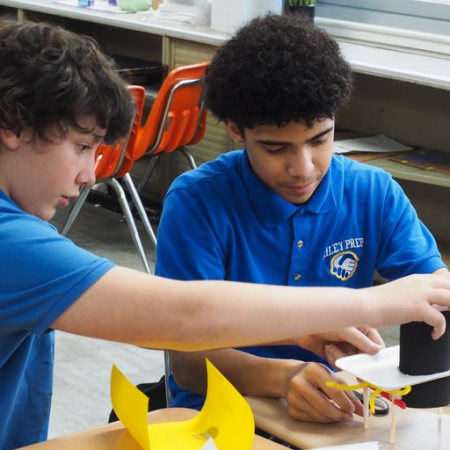

A few tables over, Gavin Rodriguez and Zavien Allende are hard at work on a new farm vehicle. They call it the “Zor T100.” It’s got wheels that can swivel to drive in any direction. “We’ve got long exhaust pipes, and we’ve got a tarp, so the crops don’t fly upwards.”

It’s practical—the pipes look like they send exhaust above the crops. But ultimately the primary function is to “look cool.” To be fair, that seems an important aspect of any innovation.

“Youth learn by doing, not by being lectured at,” Ulloa said. “I always try to tie it to something students will be familiar with. We set up activities as challenges. And because we are 4-H, we highlight leadership, teamwork, and public speaking. And most importantly, it’s fun!”

Youth are challenged to communicate about their efforts. Ulloa organizes “Shark Tank” presentations. “The activity is adapted from an MIT workshop, and it never disappoints. Youth become invested in their inventions, and they understand the local history as well as the importance of documenting and communicating about their work.

Youth are challenged to communicate about their efforts. Ulloa organizes “Shark Tank” presentations. “The activity is adapted from an MIT workshop, and it never disappoints. Youth become invested in their inventions, and they understand the local history as well as the importance of documenting and communicating about their work.

These fun, interactive experiences not only engage students' minds and imagination, they also create community. Meaghan McDermott, Director of Massachusetts 4-H has a bright vision for the future of the program. She hopes to foster a sense of belonging for youth and volunteers—whether they got involved with 4-H yesterday or have been involved for generations. “This is a program that you feel like you belong in, whether as a young person or volunteer,” she explained. Bringing 4-H programs to schools, especially urban and unserved schools, cultivates a sense of belonging and community by introducing youth to 4-H and providing challenging, fun, educational experiences.

A History of 4-H Innovation in Western Mass

In collaboration with UMass, 4-H is connecting with schools in Western Massachusetts’ urban centers. “Our STEM [science, technology, engineering, and math] program has been running in Holyoke and Springfield since 2009 when I started as an undergrad at UMass Amherst,” DuBois says.

running in Holyoke and Springfield since 2009 when I started as an undergrad at UMass Amherst,” DuBois says.

“4-H and the UMass organization I was a part of as an undergrad, Student Bridges, had a collaboration that created STEM programs. We were a group of college students that acted as tutor-mentors who were placed in either Holyoke or Springfield sites to run hands-on STEM activities with the youth participants,” says DuBois.

“I was hired as a program assistant in the spring of 2015,” adds Ulloa. “We decided to add the Arts to our program, expanding STEM programs to STEAM.”

In the following years, the programs reached beyond community centers to include middle schools. Currently, there are three school programs in action, one at Chestnut Talented and Gifted Middle School and two at Kiley Prep. Projects like the Design Challenge are part of 4-H’s national curricula. Student participants tend to come from under-served and under-represented communities, and these activities connect them directly to career possibilities in STEAM.

“When I delive r 4-H programs to schools in urban settings, I feel at home,” says Ulloa. “I am a product of Springfield Public Schools and recognize the need to instill a love and desire for the STEM fields in youth from these communities. Youth should realize that they too can succeed in these fields—that if an ELL [English language learner] young female like myself can excel in these seemingly challenging subjects, they can, too. I want them to envision themselves, often for the first time, as future scientists, engineers, or artists; as someone who has a lot to contribute not just in the classroom, but in the community, as well.”

r 4-H programs to schools in urban settings, I feel at home,” says Ulloa. “I am a product of Springfield Public Schools and recognize the need to instill a love and desire for the STEM fields in youth from these communities. Youth should realize that they too can succeed in these fields—that if an ELL [English language learner] young female like myself can excel in these seemingly challenging subjects, they can, too. I want them to envision themselves, often for the first time, as future scientists, engineers, or artists; as someone who has a lot to contribute not just in the classroom, but in the community, as well.”

DuBois adds, “For me, what always stands out is when the young people become engaged in the activities and are visibly enjoying themselves. I love hearing that science isn’t as intimidating to them as it once was, and that they can see themselves in college or learning a trade that has something to do with the curriculum we’ve run.”

“Our programs highlight a variety of careers in STEM,” Ulloa says. “Some of our former students have decided to pursue majors in chemical engineering, biomedical engineering, and urban design, while others have opted to get trained in electrical and HVAC.”

“It’s the right thing to do, and we are uniquely positioned in a university setting to offer the highest quality programs to historically underrepresented groups,” says DuBois.

Campus Connection

Since the program is directly tied to UMass Amherst, Ulloa says, it helps dispel ideas students might have that higher education is beyond their reach. UMass faculty and staff involved in the program and field trips have included:

- Dr. Paula Sturdevant Rees, Assistant Dean for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at the College of Engineering

- Dr. Emily Kumpel, Assistant Professor, Civil and Environmental Engineering

- Michael DiPasquale, Extension Assistant Professor, Department of Landscape Architecture and Regional Planning

- Dr. Kirby Deater-Deckard, Professor of Psychological and Brain Sciences

- Amanda Kinchla, Associate Extension Professor/Food Safety Specialist, Food Science department.

UMass also collaborates directly with Springfield school administrators to make certain the in-school programs fit well with their specific needs and curricula.

UMass faculty and staff go to the schools to meet students and discuss the importance of STEAM. These visits have the added benefit of giving the students some familiar faces when they head north to campus for field trips. What’s more, the 4-H programming makes college learning familiar: “Our programs are all hands-on, and we run them like a college class. Youth all receive a syllabus, and know exactly what lessons will be taught, our learning objectives, and a tie-in to future careers,” says DuBois.

Like most of the world, 4-H campus trips and 4-H urban programs were affected by COVID-19. “During the pandemic, we lost a lot of youth participants, but still offered virtual Bitmoji Google classrooms to our after-school community partners, as well as neuroscience and computer science-focused Zooms for our in-school partners,” DuBois explains.

A Teacher’s Perspective

Now that school’s back to in-person, science teacher Rivers enjoys the 4-H addition to her classroom. “My students respond remarkably well to the 4-H program. This is the third eight-week cycle we have participated in. There is a healthy sense of competition with the challenges that really engages my class. 4-H brings a unique engineering-design perspective.”

She says there’s an intriguing set of benefits to the program, as well. “Students in my class will compete in engineering design challenges, but 4-H offers a rich variety of challenges centered around a particular topic. The facilitators are extremely knowledgeable and there is always a story or unique set of facts that accompany every lesson. The 4-H activities utilize critical thinking and hands-on experiences without the pressure of assessments. It is more creative and less stressful for students.”

Back in the classroom after a lunch break, the students quiet down for the first presentation. It’s time to hear about Gavin and Zavien’s Zor T100 farm car. The class listens as they explain its workings, raising their hands to ask more questions.

The kids clearly understand the importance of patenting original ideas, and though it’s in some ways a small addition to a straightforward design challenge, it’s easy to see how it works a little magic. It takes the project into a new way of thinking—not just problem-solving, but critical thinking and innovation—just the kind of thinking they might find in a college classroom, or in a future STEM job.

It’s clear in the student’s engagement and in their smiles, that 4-H is planting vital seeds for professional success and entrepreneurship. There’s a whole lot more than craft supplies in store when DuBois and Ulloa roll in that 4-H wagon.