UMass Extension's Landscape Message is an educational newsletter intended to inform and guide Massachusetts Green Industry professionals in the management of our collective landscape. Detailed reports from scouts and Extension specialists on growing conditions, pest activity, and cultural practices for the management of woody ornamentals, trees, and turf are regular features. The following issue has been updated to provide timely management information and the latest regional news and environmental data.

Registration has begun for our UMass Extension GREEN SCHOOL!

Green School is going VIRTUAL for 2020! Classes will be Oct. 26 - Dec. 10.

Green School is going VIRTUAL for 2020! Classes will be Oct. 26 - Dec. 10.

This comprehensive 12-day certificate short course for Green Industry professionals is taught by UMass Extension specialists, University of Massachusetts faculty, and guest presenters.

Three Specialty Tracks Are Offered:

* Landscape Management

* Turf Management

* Arboriculture - specifically geared toward professional arborists

Find the full schedule and registration info at http://ag.umass.edu/greenschool

To read individual sections of the message, click on the section headings below to expand the content:

Scouting Information by Region

Environmental Data

The following data was collected on or about August 19, 2020. Total accumulated growing degree days (GDD) represent the heating units above a 50° F baseline temperature collected via our instruments for the 2020 calendar year. This information is intended for use as a guide for monitoring the developmental stages of pests in your location and planning management strategies accordingly.

|

MA Region/Location |

GDD |

Soil Temp |

Precipitation

|

Time/Date of Readings |

||

|

2-Week Gain |

2020 Total |

Sun |

Shade |

|||

|

CAPE |

318.5 |

1905 |

72 |

68 |

0.42 |

12:00 PM 08/19 |

|

SOUTHEAST |

348.5 |

2090 |

76 |

70 |

0.50 |

3:30 PM 8/19 |

|

NORTH SHORE |

332 |

2026 |

70 |

66 |

0.57 |

10:00 AM 8/19 |

|

EAST |

363 |

2217 |

73 |

67 |

0.47 |

5:00 PM 8/19 |

|

METRO |

281 |

2007 |

68 |

65 |

0.29 |

6:00 AM 8/17 |

|

CENTRAL |

322 |

2066.5 |

61 |

61 |

0.64 |

7:00 AM 8/19 |

|

PIONEER VALLEY |

313 |

2056 |

71 |

66 |

0.40 |

12:00 PM 8/19 |

|

BERKSHIRES |

277.5 |

1858.5 |

70 |

63 |

0.97 |

8:30 AM 8/19 |

|

AVERAGE |

319 |

2028 |

70 |

66 |

0.53 |

_ |

|

n/a = information not available |

||||||

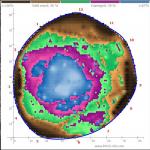

Drought conditions have worsened in our state. Updated on 8/18, this map shows some of MA in category D2, "Severe Drought", with the rest classified as either "Moderate Drought" (D1) or "Abnormally Dry" (D0): https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?MA

To track water use restrictions/bans by town, regularly check the MassDEP map: https://www.mass.gov/doc/water-use-restrictions-map/download

Phenology

| Indicator Plants - Stages of Flowering (BEGIN, BEGIN/FULL, FULL, FULL/END, END) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

PLANT |

CAPE |

SE |

NS |

EAST |

METRO |

CENT |

PV |

BERK |

|

Clematis paniculata (sweet autumn Clematis) |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

Polygonum cuspidatum (Japanese knotweed) |

Begin |

Begin |

Begin |

* |

* |

Begin |

Begin |

* |

|

Lythrum salicaria (loosestrife) |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

|

Hibiscus syriacus (rose-of-Sharon) |

Full |

End |

* |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

|

Clethra alnifolia (summersweet Clethra) |

Full |

Full |

Full/End |

Full |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full |

Full |

|

Hydrangea paniculata (panicle Hydrangea) |

Full |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full |

Full |

|

Buddleia davidii (butterfly bush) |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

* |

|

Euonymus alatus (winged Euonymus) |

* |

End |

End |

* |

Full/End |

* |

Full/End |

End |

|

Styphnolobium japonicum (L.) Schott (Japanese pagoda tree) |

* |

Full |

End |

* |

* |

* |

Full/End |

* |

| * = no activity to report/information not available | ||||||||

Regional Notes

Cape Cod Region (Barnstable)

General Conditions: The average temperature for the period of Aug 5 – Aug 19 was 73˚F with a high of 88˚F on Aug. 11 and a low of 57˚F Aug 17. These past two weeks have seen variable weather, with warmer than average temperatures from Aug 9-12 and cooler than average temperatures from Aug 15-17. The latter days were also cloudy with high relative humidity. Less than half an inch of precipitation occurred in Barnstable during the period, most occurring in a shower on the morning of Aug 18 and a little drizzle on Aug 16 & 17. Some locations saw slightly more precipitation from the Aug.18 shower. However, it was not nearly enough precipitation to alleviate water stress in plants. Both topsoil and sub soil moisture remain short/dry.

Pests/Problems: The main problem during the period has been water stressed plants as dry conditions continue to persist. Scorch, premature defoliation and some plant failures have been seen in the landscape as a result of water stress. Unirrigated lawns which go dormant during summer heat and stress are likely to suffer significant damage instead of bouncing back when cool weather returns. Insect pests seen during the period include lecanium scale nymphs which can be found feeding on leaves of numerous trees and shrubs. Their honeydew is inviting the sooty mold now covering everything in areas with high lecanium scale. Nantucket pine tip moth is the other most noticeable widespread insect; it’s causing damage to pitch pine. Other insects or insect damage observed during the period include Euonymus scale on wintercreeper Euonymus, fall webworm on apple, black turpentine beetle damage to pitch pine, white pine weevil damage to white pine, lacebugs on azalea, Andromeda, and sycamore, chilli thrips on bigleaf Hydrangea, Hibiscus sawfly on hardy Hibiscus, tarnished plant bug on Dahlia, two spotted spider mite on butterfly bush, columbine leafminer on columbine, sunflower moth damaging Echinacea flowers.

Disease symptoms or signs observed during the period include lots of powdery mildew on many different plants, apple scab on crabapple, Cercospora leaf spot on bigleaf Hydrangea and oak leaf Hydrangea, boxwood blight on boxwood, crown rot on shasta daisy and hollyhock rust on hollyhock. We are at a point in time when these plants are likely to have lasting damage instead of quickly bouncing back when cool weather returns. Populations of yellow jackets and whitefaced hornets are becoming more noticeable. Solitary ground wasps like great digger wasps and cicada killers are also very active. The sounds of crickets and katydids at night has been almost deafening. Keep yourself protected from ticks and mosquitoes while working outside. Rabbits are abundant and tunneling from moles or voles has been recently seen in lawns.

Southeast Region (Dighton)

General Conditions: We've had a dismally dry period with high temperatures, high humidity and little relief. Unirrigated lawns in full sun are reduced to straw. Crabgrass, yellow nutsedge, spotted spurge, yellow wood sorrel, and more weeds are making advances on dormant turf. Nothing has any turgor. By midday, perennials have wilted. Trees are dropping leaves early. Birch, swamp red maple, glossy buckthorn and poison ivy on exposed locations or shallow soils are showing color. Ailanthus seeds have begun to turn red. Vernal streams and wetlands are bone dry. Desperate leopard frogs are appearing in bird baths and swimming pools. Petunias stopped flowering and only picked up again in the last few days as daytime temperatures moderated. Crowds of mugwort, ragweed and lambsquarters wave hauntingly at passing vehicles along roadways. The small birds, finches and sparrows are beginning to flock up while foraging for seed. Murmurations of starlings can already be observed in the reedy fens of the Hockomock along Rt 24 in West Bridgewater. Both black and yellow swallowtail butterflies are still about, as are hummingbird moths, mud daubers and carpenter bees. Hummingbirds are in fierce competition for the few plants producing nectar.

I've noticed the following plants to be in flower: Reynoutria japonica (synonyms Fallopia japonica and Polygonum cuspidatum - Japanese knotweed), Albizia julibrissin (silktree), Hibiscus spp., H. syrica (rose of Sharon), moscheutos (swamp rose mallow), Hydrangea paniculata (Hydrangea), Cannabis spp. (marijuana), Rudbeckia hirta (black-eyed-Susan), Phlox paniculata (garden Phlox), Salvia yangii (Russian sage), Echinacea purpurea (coneflower), Solidago spp. (goldenrod), Artemisia vulgaris (mugwort), Ambrosia artemisiifolia (ragweed), Erigeron canadensis (horseweed, marestail), Daucus carota (Queen Ann's lace), Verbascum thapsus (common yellow Mullein), Oenothera biennis (evening primrose), Eutrochium purpureum (Joe-Pye-weed), Buddleia davidi (butterfly bush), Sedum spp. (Sedum 'Autumn Joy'), Franklinia alatamaha (Franklin tree), Linaria vulgaris (yellow toadflax), Campsus radicans (trumpet vine), Lythrum salicaria (purple loosestrife), Hosta spp. (plantain lily) and Clethra alnifolia (summer sweet)

Pests/Problems: Judging from the water loss in my water gardens, the evapotranspiration rate was better than four inches over this period. Although municipal water bans added to the difficulty of keeping potted or new plantings alive, drought is a far second to mosquitoes and the diseases they vector in the ranking for concerns in the landscape. Both EEE and West Nile Virus have been reported in MA so far this season. At least one case of EEE was in Middleboro. In addition to PPE, take the time while out on your properties to monitor for potential breeding sites. Stagnant water may go unnoticed by your clients and become a public health threat. Skunk damage is already a problem on lawns due to their feeding activity on grubs. Brown rot was observed on peach.

North Shore (Beverly)

General Conditions: Dry, hot and humid conditions continued into this reporting period (Aug 5 – Aug 19) except for the last few days when the temperatures and humidity went down to more comfortable levels. Temperatures above 90℉ were recorded for three of the 14 days. The average daily temperature was 71℉ with the maximum temperature of 94℉ recorded on August 11 and the minimum temperature of 58℉ recorded on August 19. Very little rain was received, approximately 0.57 inches recorded at Long Hill during the last two weeks. Woody plants seen in bloom include: silk tree or mimosa (Albizia julibrissin), panicle Hydrangea (Hydrangea paniculata), butterfly bush (Buddleia davidii), rose-of-Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus), chaste tree (Vitex agnus-castus), Daphne (Daphne spp.) Hibiscus ‘Fireball’ and summersweet Clethra (Clethra alnifolia). Herbaceous plants seen in bloom include: garden Phlox (Phlox paniculata), Hostas (Hosta spp.), Sedums (Sedum spp.), black eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta), coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), milkweed (Asclepias spp.), water lily (Nymphaea odorata) and summer annual plants.

Pests/Problems: Powdery mildew was observed on lilac and garden Phlox. Magnolia or tuliptree scales were observed on Magnolia. See the Insects section below for more information. Soils are very dry and most lawns have turned brown and dormant. Some shrubs are also showing drought stress. Newly planted shrubs should be watered. Mosquitoes and ticks have slowed down, so the risk of a bite is low but it is still important to use repellents when working outdoors especially at dawn and dusk.

East Region (Boston)

General Conditions: It has been hot and humid with very little precipitation. High temperatures ranged from 72˚F to 101˚F, averaging 90˚F. Low temperatures ranged from 59˚F to 73˚F, averaging 65˚F. We experienced a 6-day heat wave Aug 8-13 as temperatures topped 100˚F on three consecutive days from Aug 10-12. Finally, on Aug 14 and 15, remnants of tropical storms Josephine and Kyle passed by and cooled things off. We received precipitation on two occasions totaling 0.47”. Perennial borders continue to add an abundance of color to the landscape and keep the pollinators busy. Cicadas have emerged.

Pests/Problems: Soils remain dry and premature leaf drop continues throughout the landscape. Mildew is prevalent on lilac, peony, Phlox and many other susceptible plants. Lacebug is thriving on Cotoneaster, hawthorn and Pieris. Viburnum leaf beetle adults have begun feeding on the foliage of susceptible Viburnum.

Metro West (Acton)

General Conditions: The hot and humid weather continued into this reporting period (Aug 5 – Aug 19). This area experienced its fourth heat wave of the summer beginning on August 9th and including and ending on the 13th. Overall, there have been 29 days this summer with temperatures recorded in the 90s and 16 of those days occurred in July, 7 in June and 6 in August. At this time last year, there were a total of 15 days recorded with temperatures of 90°or more. For August, the historical monthly average precipitation is 3.72” and as of the 16th, a total of 0.75” has been recorded. Observed in some stage of bloom this past couple of weeks were the following woody plants: Buddleia spp. (butterflybush), Campsis radicans (trumpet vine), Clethra alnifolia (summersweet), Hibiscus syriacus (rose-of-Sharon), Hydrangea paniculata (panicle Hydrangea and its many cultivars including 'Tardiva'), Potentilla fruiticosa (Potentilla), Rhus typhina (staghorn sumac), Rosa 'Knockout' (Knockout family of roses), and R. spp. (rose). Perennials seen in some stage of bloom this past two weeks were the following: Achillea millefolium (yarrow), Alcea rosea (hollyhocks), Asclepias syriaca (common milkweed), Astilbe spp. (false spirea), Boltonia asteroides (Bolton’s aster), Campanula persicifolia (peach-leafed bell flower), C. takesimana ‘Elizabeth’ (bell flower), Cichorium intybus (chicory), Coreopsis spp. (tickseed), C. verticillata (threadleaf Coreopsis), Daucus carota (Queen Anne's lace), Echinacea purpurea (coneflower and its many cultivars), Eutrochium purpureum (Joe pye weed), Geranium sanguineum (cranesbill Geranium), Gaillardia aristata (blanket flower), Hemerocallis spp. (daylily), Hosta spp. (plantain lily), Kirengeshoma palmata (yellow wax bells), Leucanthemum spp. (shasta daisy), Lilium spp. (lily), Lysimachia clethroides (gooseneck loosestrife), Lythrum salicaria (purple loosestrife, a non-native invasive), Monarda didyma (bee-balm), Patrinia gibbosa (Patrinia), Perovskia atriplicifolia (Russian sage), Phlox carolina (Carolina Phlox), P. paniculata (garden Phlox), Platycodon grandiflorus (balloon flower), Rudbeckia fulgida var. sullivantii 'Goldsturm' (black-eyed Susan), Sedum ‘Rosy Glow’ (stonecrop), Senna marilandica (wild Senna) and Solidago spp. (goldenrod).

Pests/Problems: This area remains in a moderate drought according to the US Drought Monitor: https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?MA. Rain was recorded on only 2 days during this past two-week reporting period for a total of 0.29”. Trees and shrubs are stressed and signs of this stress are evident including early fall color, leaf drop, wilting foliage and canopy dieback. Setting seed and quite visible is Ailanthus altissima (tree of heaven). Look for it growing along roadsides and in parking lots and medians.

Central Region (Boylston)

General Conditions: This reporting period featured wild temperature swings, including some much-appreciated cool periods. The majority of the week from August 5-12 was hot and humid, and featured a heat wave with three consecutive days of above 90˚F temperatures. The heat finally broke on August 15 and the high temperature did not even touch 70˚F on Sunday, August 16. Some much needed rain fell this period. Just about ½-inch of precipitation on August 18 gave a brief respite for gardeners who have been constantly watering. There is still much in bloom in the garden, including many gorgeous late season perennials and shrubs. Observed during this reporting period were Anemone ‘Serenade’ (Japanese windflower), Eurybia divaricata (white wood aster), Eutrochium maculatum (spotted Joe-Pye weed), Geranium ‘Azure Rush’ (cranesbill), Hydrangea arborescens ‘Hayes Starburst’ (smooth Hydrangea), Ligularia dentata ‘Osiris Fantaisie’ (leopard plant), Lobelia cardinalis (cardinal flower), Lobelia siphilitica (great blue Lobelia), Rudbeckia laciniata (cutleaf coneflower, green-head coneflower), Salvia yangii (formerly Perovskia atriplicifolia, Russian sage), Silphium perfoliatum (cup plant), Vernonia noveboracensis (New York ironweed), Veronicastrum virginicum (Culver’s root), and Vitex x ‘Bailtexone’ (Flip Side® chaste tree).

Pests/Problems: The region continues to suffer from “Moderate Drought” conditions. The most recent data from the U.S. Drought Monitor was from August 18. It would not come as a surprise if the region was upgraded to Severe Drought without substantial rainfall in coming weeks. A small number of blister beetles were observed on Japanese anemone. This beetle can be handpicked for control, but be forewarned - they can exude the chemical cantharidin that can cause blisters on skin. Many non-irrigated areas across the region are exhibiting signs of drought stress such as premature leaf drop, wilting of leaves and early flower drop.

Pioneer Valley Region (Easthampton)

General Conditions: The days are getting shorter and the shadows are getting longer as we enter the last days of August in the Pioneer Valley. This reporting period started with hot, humid and dry conditions. It was a continuation of the sweltering summer of 2020 that started in June and never quit. High temperatures consistently approached 90°F with high humidity and very little relief at night. While August is typically one of our drier months, rainfall to date is well below-normal, as it has been for most of the growing season. Only one rain event (8/17) was recorded at the Easthampton reporting station over this two-week stretch. The NRCC has provided a nice summary of the conditions during the first half of August. Precipitation was minimal in the eastern and southern portions of the tri-county region while some areas west and north fared better. While precipitation varied somewhat, temperatures were consistently 4–6°F above normal throughout the valley. Thankfully, on Saturday, 8/15 temperatures cooled dramatically and the humidity dissipated, ushering in a stretch of near perfect weather (sunny skies, upper 70s to low 80s and low humidity). However, at the time of writing another warm-up is on the horizon. Surface soils remain bone dry in full-sun landscapes although there is some lingering moisture in the subsurface soils, depending on the soil type and texture. Supplemental watering is essential right now but efforts should be made to ensure the root zone is being properly wetted. Check soils after irrigation systems, if present, have run to confirm they are functioning properly.

Symptoms of drought stress continue to appear throughout the landscape. Older leaves/needles are yellowing and prematurely shedding from hemlock, birch, linden, katsura, Rhododendron, azalea and tulip poplar on the UMass campus. Numerous perennials, too many to list, are wilting and drooping as well. Turfgrasses are dry and crunchy. Stewartia and katsura are developing their late season marginal leaf browning due to heat stress. Upper canopy foliage on Viburnums is starting to redden as well. Despite the dry and hot weather, Hydrangeas continue to shine in the landscape right now with their large blooms. Mosquito populations have been suppressed by the dry weather but EEE has been confirmed in the state (see Insect section below for details). A large, sandy mound created by the eastern cicada killer (Sphecius speciosus) was observed next to a residential driveway. It appeared approximately four weeks ago but the wasps have only been seen for the past week or so (see photo below). There are two sand mounds, with the larger one measuring 10” wide and 4” tall. An adult wasp was even seen bringing a paralyzed cicada into the nest, where it will serve as a food source for hatching larvae. While these ground-dwelling wasps are very large and appear menacing, they pose little threat to humans. It’s been possible to sit next to the nest and observe them with little reciprocal interest on their part. While “Murder Hornets” have created quite a stir this summer, there are several large, native wasps in our landscapes that are not aggressive.

Pests/Problems: Drought stress remains the most pressing issue right now. Newly planted trees and shrubs should be watered regularly, regardless of how much sun they receive. Be mindful not to overwater, especially for yews and Rhododendrons. White pine weevil injury is readily visible now (pictured here on an eastern white pine at UMass). Wood-rotting fungi continue to appear, such as the northern tooth fungus (photographed on a sugar maple on 8/17) and various root and butt rot pathogens of oak. Crabapples and apples continue to shed foliage from apple scab and drought. By late August, some trees may be badly defoliated, but history suggests these trees should persevere without lasting injury. There’s been very little tar spot on Norway maple this season, likely due to dry conditions in mid- and late May. A variety of leaf spots and blotches can be found at present on woody plants. While some infections take place early in the growing season, the symptoms may not become apparent until late in the season. As such, they cause little damage and don’t warrant management. Crabgrass growth has slowed with the dry weather and recent cool nights.

Berkshire Region (Great Barrington)

General Conditions: It has been a typical August thus far, i.e. hazy, hot and humid. For most of the past two weeks, the average daily temperature has been higher than normal and it’s been much drier than normal. A high temperature of 88˚F was reached on 8/11 and a low temperature of 50˚F was recorded this morning, 8/19, at this site in West Stockbridge. The main concern this growing season has been the lack of rainfall. As of 8/18, total year to date rainfall as measured at Pittsfield Municipal Airport is 21.78 inches. Normal year to date rainfall is 28.22. That’s a deficit of 6.44 inches. As mentioned in previous reports, rain events vary considerably in the county. For example, over the last two weeks, total rainfall measured in West Stockbridge is 0.97 inches, in nearby Richmond it is 0.44 inches, in Pittsfield it is 0.42 inches and in North Adams it is 0.78 inches. Often the differences are even much greater due to the very diverse topography from South County bordering on Connecticut to North County bordering on Vermont. Soil moisture levels are low but growth of turfgrass has been steady if not vigorous.

Pests/Problems: The drought has affected the growth of some plants in managed landscapes. Needled evergreens on the driest sites are dropping their needles somewhat prematurely and in the worst cases the remaining needles are yellowing. Premature color change in many deciduous species is apparent. Though turfgrass overall is growing well, drying and browning of grass is most apparent where soil compaction exists, e.g. frequent paths across lawns. On a large scale, core aeration is advisable, especially later this month and into September. This could be followed up with a topdressing of humus or compost. Pest problems are surprisingly low at this time. Spider mites on ornamental pear foliage and a few Japanese, Oriental and Asiatic garden beetles still linger in some landscapes. However, population levels of wasps, mosquitoes, eye gnats, and deer ticks remain high. Browsing of landscape plants by deer, woodchucks, rabbits, chipmunks and voles are a frequent problem. Gnawing of stems of smooth barked and sapling trees this past winter is resulting in wilting and death of affected trees. Diseases seem to be the biggest concern now, especially with various leaf spot and leaf blight problems on a wide range of trees, shrubs, and herbaceous species. Powdery mildew is common on many lilacs and many herbaceous plants. Verticillium infection was observed affecting the health of Cotinus (smoketree).

Regional Scouting Credits

- CAPE COD REGION - Russell Norton, Horticulture and Agriculture Educator with Cape Cod Cooperative Extension, reporting from Barnstable.

- SOUTHEAST REGION - Brian McMahon, Arborist, reporting from the Dighton area.

- NORTH SHORE REGION - Geoffrey Njue, Green Industry Specialist, UMass Extension, reporting from the Long Hill Reservation, Beverly.

- EAST REGION - Kit Ganshaw & Sue Pfeiffer, Horticulturists reporting from the Boston area.

- METRO WEST REGION – Julie Coop, Forester, Massachusetts Department of Conservation & Recreation, reporting from Acton.

- CENTRAL REGION - Mark Richardson, Director of Horticulture reporting from Tower Hill Botanic Garden, Boylston.

- PIONEER VALLEY REGION - Nick Brazee, Plant Pathologist, UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab, temporarily reporting from Easthampton.

- BERKSHIRE REGION - Ron Kujawski, Horticultural Consultant, reporting from Great Barrington.

Woody Ornamentals

Diseases

Recent pests and pathogens of interest seen in the UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab https://ag.umass.edu/services/plant-diagnostics-laboratory:

Stem failure of Norway spruce (Picea abies) due to root and butt rot caused by the velvet top fungus, Phaeolus schweinitzii. The tree is approximately 60- to 80-years-old and was one of several planted in a row at the edge of a parking lot on the UMass campus. Many of the trees suffered root severing, compaction and crushing during an expansion and repaving of the parking lot in 2008. This particular tree exhibited excessive basal tapering and, more recently, a thinning crown. More importantly, fruiting bodies of Phaeolus have appeared next to the tree for approximately 10 years, serving many plant pathology and mycology students. Winds from Tropical Storm Isaias exposed the structural weakness in the lower trunk and the tree suffered stem breakage. Overhead view of the stump corroborated the findings from sonic and electrical resistance tomography scanning, which predicted decay (middle image; green, magenta and blue represents decaying wood) with a cavity (right image; area of red in the center represents high resistance). Several other trees in the row are also infected and have either uprooted or suffered stem breakage under loading from strong winds within the past decade.

Stem failure of Norway spruce (Picea abies) due to root and butt rot caused by the velvet top fungus, Phaeolus schweinitzii. The tree is approximately 60- to 80-years-old and was one of several planted in a row at the edge of a parking lot on the UMass campus. Many of the trees suffered root severing, compaction and crushing during an expansion and repaving of the parking lot in 2008. This particular tree exhibited excessive basal tapering and, more recently, a thinning crown. More importantly, fruiting bodies of Phaeolus have appeared next to the tree for approximately 10 years, serving many plant pathology and mycology students. Winds from Tropical Storm Isaias exposed the structural weakness in the lower trunk and the tree suffered stem breakage. Overhead view of the stump corroborated the findings from sonic and electrical resistance tomography scanning, which predicted decay (middle image; green, magenta and blue represents decaying wood) with a cavity (right image; area of red in the center represents high resistance). Several other trees in the row are also infected and have either uprooted or suffered stem breakage under loading from strong winds within the past decade. Severe infestation of the Cryptomeria scale (CS; Aspidiotus cryptomeriae) on Fraser fir (Abies fraseri). Trees are eight-years-old and growing at a Christmas tree farm with full sun and overhead irrigation. In July of this year, yellow flecking/spotting was observed on the upper surface of the needles and the symptoms have only intensified since then. The submitted sample quickly revealed a severe infestation of this invasive, armored scale. The CS is very similar to the elongate hemlock scale, also common on landscape fir, but is readily distinguishable by its “fried egg” appearance. Specifically, the scales are yellow-orange with a white, waxy cover surrounding their body. Regular and careful scouting of conifers for armored scale infestations in the landscape is essential so that intervention can take place before populations reach epidemic levels.

Severe infestation of the Cryptomeria scale (CS; Aspidiotus cryptomeriae) on Fraser fir (Abies fraseri). Trees are eight-years-old and growing at a Christmas tree farm with full sun and overhead irrigation. In July of this year, yellow flecking/spotting was observed on the upper surface of the needles and the symptoms have only intensified since then. The submitted sample quickly revealed a severe infestation of this invasive, armored scale. The CS is very similar to the elongate hemlock scale, also common on landscape fir, but is readily distinguishable by its “fried egg” appearance. Specifically, the scales are yellow-orange with a white, waxy cover surrounding their body. Regular and careful scouting of conifers for armored scale infestations in the landscape is essential so that intervention can take place before populations reach epidemic levels.- Infestation of the white pine weevil (Pissodes strobi) and subsequent stem cankering caused by Diplodia sapinea on Vanderwolf’s Pyramid limber pine (Pinus flexis ‘Vanderwolf’s Pyramid’). Tree is approximately 10- to 12-years-old and has been present at the site for three years. It grows in full sun in a clay-loam soil with hand-watering as needed. In mid-July, drooping of one co-dominant leader was observed. Investigation of the wilting revealed other adjacent shoots were also wilting. The dead parts were pruned out, leaving the other co-dominant leader in place. The submitted shoot had evidence of white pine weevil feeding but it also exhibited rough, cracked and splitting bark with resinosis. Microscopic evaluation revealed Diplodia was also present and likely colonized the declining stems after the infestation.

- Rhizosphaera needle cast, caused by Rhizosphaera kalkhoffii, on blue spruce (Picea pungens). Tree is roughly 20-years-old and has been present at the site for over 15 years. It resides in full sun but is situated on a windy bluff on the south shore of Martha’s Vineyard in sandy soils. This summer, needle browning and premature shedding was observed, followed by branch dieback. Rhizosphaera is very common on blue spruce, leading to a progressively worsening dieback, in conjunction with other stresses.

- Fire blight, caused by Erwinia amylovora, on Bradford pear (Pyrus calleryana ‘Bradford’) and apple (Malus domestica). The pear is roughly 45-years-old and in late spring, exhibited a branch tip dieback. The apple is about 25-year-old and in early July, a sporadic dieback throughout the canopy was observed. Both trees reside in full sun and receive supplemental water. The submitted pear sample had blackened leaves, petioles and shoots along with the characteristic curling of the shoot tip. The apple symptoms were not as obvious, but it still had blackened leaves and petioles. The apple was also suffering from stem cankering caused by Phomopsis. Opportunistic cankering fungi will often invade tissues damaged/killed by fire blight and cause further dieback.

- Hemlock-blueberry rust, caused by Thekopsora minima, on eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis). The tree is approximately 25-years-old and has been present at the site for nearly as long. It resides in a full sun setting with sandy soils. The sloped site is very dry and Rhododendrons growing underneath are wilting. This season, intermittent needle yellowing and premature shedding was observed. Thekopsora produces white-colored, tube-like projections from the underside of infected hemlock needles. The spores produced from these tubes (aeciospores) disperse to infect blueberry (Vaccinium) or Rhododendron/azalea (Rhododendron). Typically, the disease does not result in serious damage and does not warrant management. In this case, the under-planted Rhododendrons (suspected as the alternate host) could be removed.

- Browning and dieback of Dark American arborvitae (Thuja occidentalis ‘Nigra’) caused by the arborvitae leafminer (Argyresthia thuiella) and needle blight (Pestalotiopsis). Screening row of 30 arborvitaes, spanning approximately 100’, which have been trimmed into a dense, squared hedgerow. Trees are approximately 20-years-old and were planted 15 years ago. In late June of this year, the center of the hedge began browning from the bottom with dieback spreading upward and outward to adjacent trees. Supplemental water is provided via lawn sprinklers, which may have contributed to the needle blight development. Submitted roots were healthy and no belowground issues are suspected.

Report by Nick Brazee, Plant Pathologist, UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab, UMass Amherst.

Insects

Did you miss the live broadcasts of UMass Extension’s Invasive Insect Webinar Series? No problem! View the archived recordings of all seven webinars here:https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/invasive-insect-webinars

A Review of Beneficial Insects in the Landscape:

It can never hurt to be reminded that the grand majority of insects found in our landscapes are in fact, not pests. I know this may be difficult to believe when that statement is followed by a long list of pests of trees and shrubs as well as pests of public health concern – but truly, the majority of insects we run into on a daily basis are either innocent bystanders (and may have no impact on trees and shrubs) or even beneficial (they provide many ecosystem services such as decomposition and may even provide free pest management services).

Therefore, it is prudent to remind ourselves that beneficial insects are naturally present in our landscapes and to act accordingly. Never attempt to manage an insect that you have not accurately identified first. For the purposes of tree and shrub insect pest management, this review will focus on insects that are either predators, parasites, or parasitoids of common insect pests of trees and shrubs. Please note that the following lists do not represent all known beneficial insects found in the landscape:

Predators:

- Coccinellidae: Lady beetles, Ladybugs, Ladybird beetles (Coleoptera)

- Predators of: aphids, small caterpillars, small beetles, armored scales, insect eggs, mites, and thrips

- Adults may require: pollen, nectar, or honeydew

- Carabidae: Ground beetles (Coleoptera)

- Predators of: eggs and larvae of root maggots, caterpillars, aphids, beetle larvae, weed seeds, snails, and slugs

- Additional requirements: many are restricted to the soil surface and may be poor climbers, while some specialists are not

- Nabidae: Damsel bugs (Hemiptera)

- Predators of: smaller insects, including aphids and caterpillars, insect eggs

- Additional requirements: may be common in grassy fields

- Reduviidae: Assassin bugs (Hemiptera)

- Predators of: aphids, leafhoppers, small caterpillars, beetle eggs and larvae; some are ambush predators at flowers and will capture flies, bees, and other flower visitors

- Chrysopidae: Green lacewings (Neuroptera)

- Predators of: aphids, small caterpillars, beetle larvae, insect eggs as larvae

- Adults may require: pollen, nectar, or honeydew; adults in the genus Chrysopa feed on small insects

- Hemerobiidae: Brown lacewings (Neuroptera)

- Predators of: aphids, caterpillars, beetle larvae, insect eggs as both larvae and adults, woolly aphids, mealybugs, scales, and mites

- Additional requirements: dense vegetation, trees and shrubs

- Syrphidae: Hoverflies, Syrphid flies, Flower flies (Diptera)

- Predators of: aphids and other soft-bodied insects as larvae

- Adults may require: nectar, pollen, and are frequently seen at flowers (mimic bees/wasps)

Parasites/Parasitoids:

- Tachinidae: Tachinid flies (Diptera)

- Parasites of: immature beetles, butterflies, moths, sawflies, earwigs, grasshoppers, true bugs; adults may feed on nectar

- Some lay eggs directly on the body of the host; some lay eggs on plant material and then are ingested by the host

- Braconidae: Braconid wasps (Hymenoptera)

- Parasitoid of: aphids, common parasite of caterpillars

- 1,900+ North American species; many of which specialize on specific hosts

- Ichneumonidae: Ichneumon wasps (Hymenoptera)

- Parasitoids of: common parasite of caterpillars, beetles, sawflies, and other wasps

- Ovipositors of some species can penetrate wood to gain access to host insects

Resources for Beneficial Insect Identification and Further Information:

- Identifying Natural Enemies in Crops and Landscapes (Michigan State University)

- Good Garden Bugs (Ohio State University)

- Garden Insects of North America: The Ultimate Guide to Backyard Bugs (Second Edition: Colorado State University and The Ohio State University)

- This second edition has added a large section on beneficial insects

- https://press.princeton.edu/titles/11145.html

Insects and Other Arthropods of Public Health Concern:

- Mosquitoes: On July 3, 2020 the Massachusetts Department of Public Health announced that the eastern equine encephalitis (EEE) virus had been detected in mosquitoes in Massachusetts for the first time this year: https://www.mass.gov/news/state-public-health-officials-announce-seasons-first-eee-positive-mosquito-sample-0 . For more information about the first 2020 EEE detection and ways to protect yourself, visit the link above.

For current information, including searchable risk maps for both EEE and WNV in Massachusetts, visit:https://www.mass.gov/info-details/massachusetts-arbovirus-update

According to the Massachusetts Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Science and the Department of Public Health, there are at least 51 different species of mosquito found in Massachusetts. Mosquitoes belong to the Order Diptera (true flies) and the Family Culicidae (mosquitoes). As such, they undergo complete metamorphosis, and possess four major life stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Adult mosquitoes are the only stage that flies and many female mosquitoes only live for 2 weeks (although the life cycle and timing will depend upon the species). Only female mosquitoes bite to take a blood meal, and this is so they can make eggs. Mosquitoes need water to lay their eggs in, so they are often found in wet or damp locations and around plants. Different species prefer different habitats. It is possible to be bitten by a mosquito at any time of the day, and again timing depends upon the species. Many are particularly active from just before dusk, through the night, and until dawn. Mosquito bites are not only itchy and annoying, but they can be associated with greater health risks. Certain mosquitoes vector pathogens that cause diseases such as West Nile virus (WNV) and eastern equine encephalitis (EEE).

For more information about mosquitoes in Massachusetts, visit: https://www.mass.gov/service-details/mosquitoes-in-massachusetts

There are ways to protect yourself against mosquitoes, including wearing long-sleeved shirts and long pants, keeping mosquitoes outside by using tight-fitting window and door screens, and using insect repellents as directed. Products containing the active ingredients DEET, permethrin, IR3535, picaridin, and oil of lemon eucalyptus provide protection against mosquitoes.

For more information about mosquito repellents, visit:https://www.mass.gov/service-details/mosquito-repellents and https://www.cdc.gov/features/stopmosquitoes .

- Deer Tick/Blacklegged Tick: Check out the archived FREE TickTalk with TickReport webinars available here:https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/ticktalk-with-tickreport-webinars . Previous webinars including information about deer ticks and associated diseases, ticks and personal protection, and updates from the Laboratory of Medical Zoology are archived at the link above.

The next live webinar will be held on September 9, 2020: Biology of Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases- Speaker: Dr. Daniel Sonenshine, Professor Emeritus, Old Dominion University; Laboratory of Malaria and Vector Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIH)

Dr. Rich will host Dr. Daniel Sonenshine, preeminent tick biologist who quite literally wrote the book on ticks (Biology of Ticks in two volumes, co-authored with Dr. R. Michael Roe). Dr. Sonenshine’s research interest in ticks precedes the discovery of Lyme disease in North America and he is thus uniquely qualified to provide a historical context for this public health challenge. To register for the next TickTalk, visit:https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/ticktalk-with-tickreport-webinars

Ixodes scapularis nymphs (immatures) are active, and may be encountered at this time, through August. Nymphs will have already taken a blood meal, and therefore can be infected with disease causing pathogens. It is important to protect yourself against ticks and be especially vigilant for tiny, difficult to see nymphs. For images of all deer tick life stages, along with an outline of the diseases they carry, visit: http://www.tickencounter.org/tick_identification/deer_tick .

Anyone working in the yard and garden should be aware that there is the potential to encounter deer ticks. The deer tick or blacklegged tick can transmit Lyme disease, human babesiosis, human anaplasmosis, and other diseases. Preventative activities, such as daily tick checks, wearing appropriate clothing, and permethrin treatments for clothing (according to label instructions) can aid in reducing the risk that a tick will become attached to your body. If a tick cannot attach and feed, it will not transmit disease. For more information about personal protective measures, visit: http://www.tickencounter.org/prevention/protect_yourself .

Have you just removed an attached tick from yourself or a loved one with a pair of tweezers? If so, consider sending the tick to the UMass Laboratory of Medical Zoology to be tested for disease causing pathogens. To submit a tick to be tested, visit: https://www.tickreport.com/ and click on the blue “Order a TickReport” button. Results are typically available within 3 business days, or less. By the time you make an appointment with your physician following the tick attachment, you may have the results back from TickReport to bring to your physician to aid in a conversation about risk.

The UMass Laboratory of Medical Zoology does not give medical advice, nor are the results of their tests diagnostic of human disease. Transmission of a pathogen from the tick to you is dependent upon how long the tick had been feeding, and each pathogen has its own transmission time. TickReport is an excellent measure of exposure risk for the tick (or ticks) that you send in to be tested. Feel free to print out and share your TickReport with your healthcare provider.

Wasps/Hornets: Many wasps are predators of other arthropods, including pest insects such as certain caterpillars that feed on trees and shrubs. Adult wasps hunt prey and bring it back to their nest where young are being reared, as food for the immature wasps. A common such example are the paper wasps (Polistes spp.) who rear their young on chewed up insects. They may be seen searching plants for caterpillars and other soft-bodied larvae to feed their young. Paper wasps can sting, and will defend their nests, which are open-celled paper nests that are not covered with a papery “envelope”. These open-celled nests may be seen hanging from eaves or other outdoor building structures. Aerial yellow jackets and hornets create large aerial nests that are covered with a papery shell or “envelope”. Common yellow jacket species include those in the genus Vespula. Dolichovespula maculata is commonly known as the baldfaced hornet, although it is not a true hornet. The European hornet (Vespa crabro) is three times the size of a yellow jacket and may be confused for the Asian giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia). The European hornet is known to Massachusetts, but the Asian giant hornet is not. If you are concerned that you have found or photographed an Asian giant hornet, please report it here: https://massnrc.org/pests/report.aspx . A helpful ID tool, although developed for Texas by the USDA, depicts common look-a-like species that we also have in MA that can be confused for the Asian giant hornet and is found here: https://agrilife.org/lubbock/files/2020/05/Asian_Giant_Hornet_Look-alikes_101_Xanthe_Shirley.pdf .

Wasps/Hornets: Many wasps are predators of other arthropods, including pest insects such as certain caterpillars that feed on trees and shrubs. Adult wasps hunt prey and bring it back to their nest where young are being reared, as food for the immature wasps. A common such example are the paper wasps (Polistes spp.) who rear their young on chewed up insects. They may be seen searching plants for caterpillars and other soft-bodied larvae to feed their young. Paper wasps can sting, and will defend their nests, which are open-celled paper nests that are not covered with a papery “envelope”. These open-celled nests may be seen hanging from eaves or other outdoor building structures. Aerial yellow jackets and hornets create large aerial nests that are covered with a papery shell or “envelope”. Common yellow jacket species include those in the genus Vespula. Dolichovespula maculata is commonly known as the baldfaced hornet, although it is not a true hornet. The European hornet (Vespa crabro) is three times the size of a yellow jacket and may be confused for the Asian giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia). The European hornet is known to Massachusetts, but the Asian giant hornet is not. If you are concerned that you have found or photographed an Asian giant hornet, please report it here: https://massnrc.org/pests/report.aspx . A helpful ID tool, although developed for Texas by the USDA, depicts common look-a-like species that we also have in MA that can be confused for the Asian giant hornet and is found here: https://agrilife.org/lubbock/files/2020/05/Asian_Giant_Hornet_Look-alikes_101_Xanthe_Shirley.pdf .

Paper wasps and aerial yellowjackets overwinter as fertilized females (queens) and a single female produces a new nest annually in the late spring. Nests are abandoned at the end of the season. Annually, queens start new nests, laying eggs, and rearing new wasps to assist in colony/nest development. Some people are allergic to stinging insects, so care should be taken around wasp/hornet nests. Unlike the European honeybee (Apis mellifera), wasps and hornets do not have barbed stingers, and therefore can sting repeatedly when defending their nests. It is best to avoid their nests, and if that cannot be done and assistance is needed to remove them, consult a professional.

Woody ornamental insect and non-insect arthropod pests to consider, a selected few:

Asian Longhorned Beetle: (Anoplophora glabripennis, ALB) is a serious invasive insect that was first detected in Massachusetts in August of 2008. The USDA has declared August as “tree check month” because this is the peak time of the year to spot ALB adults emerging from trees. For more information about tree check month, visit: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/newsroom/news/sa_by_date/sa-2020/alb-tree-check-month and https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/resources/pests-diseases/asian-longhorned-beetle/resources/alb-august-tree-check-month

Asian Longhorned Beetle: (Anoplophora glabripennis, ALB) is a serious invasive insect that was first detected in Massachusetts in August of 2008. The USDA has declared August as “tree check month” because this is the peak time of the year to spot ALB adults emerging from trees. For more information about tree check month, visit: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/newsroom/news/sa_by_date/sa-2020/alb-tree-check-month and https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/resources/pests-diseases/asian-longhorned-beetle/resources/alb-august-tree-check-month

ALB was detected for the first time in South Carolina in 2020. Asian longhorned beetle eradication programs currently exist in Massachusetts, New York, and Ohio. A homeowner is responsible for finding, reporting, and making officials aware of the infestation in South Carolina. Great job!

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) and the Clemson University’s Department of Plant Industry (DPI) are inspecting trees in Hollywood, South Carolina following the detection and identification of the Asian longhorned beetle (ALB).

On May 29, a homeowner in Hollywood, South Carolina contacted DPI to report they found a dead beetle on their property and suspected it was ALB. A DPI employee collected the insect the same day and conducted a preliminary survey of the trees on the property. Clemson’s Plant and Pest Diagnostic Clinic provided an initial identification of ALB, and on June 4, APHIS’ National Identification Services confirmed the insect. On June 11, APHIS and DPI inspectors confirmed that one tree on the property is infested, and a second infested tree was found on an adjacent property. For more information, visit: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/newsroom/stakeholder-info/sa_by_date/sa-2020/sa-06/alb-sc .

This is a good reminder for us to remain vigilant, and report any suspicious beetles or damage to trees, especially maples. Asian longhorned beetle infests 12 genera of trees, however maples are preferred hosts.

Look for signs of an ALB infestation which include perfectly round exit holes (about the size of a dime), shallow oval or round scars in the bark where a female has chewed an egg site, or sawdust-like frass (excrement) on the ground nearby host trees or caught in between branches. Be advised that other, native insects may create perfectly round exit holes or sawdust-like frass, which can be confused with signs of ALB activity.

The regulated area for Asian longhorned beetle is 110 miles2 encompassing Worcester, Shrewsbury, Boylston, West Boylston, and parts of Holden and Auburn. If you believe you have seen damage caused by this insect, such as exit holes or egg sites, on susceptible host trees like maple, please call the Asian Longhorned Beetle Eradication Program office in Worcester, MA at 508-852-8090 or toll free at 1-866-702-9938.

To report an Asian longhorned beetle find online or compare it to common insect look-alikes, visit: https://massnrc.org/pests/albreport.aspx or https://www.aphis.usda.gov/pests-diseases/alb/report .

More information can be found in the “Trouble Maker of the Month” section of July’s edition of Hort Notes:https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/newsletters/hort-notes/hort-notes-2020-vol-315

- Asiatic Garden Beetle: Maladera castanea adults are active and are typically most abundant in July and August. These rusty-red colored beetles are bullet-shaped and active at night. They are often attracted to porch lights. They feed on a number of ornamental plants, defoliating leaves by giving the edges a ragged appearance and also feeding on blossoms. Butterfly bush, rose, Dahlia, Aster, and Chrysanthemum can be favored hosts.

- Azalea Sawflies: One species of azalea sawfly, Arge clavicornis, is found as an adult in July and lays its eggs in leaf edges in rows. Larvae are present in August and September. Remember, sawfly caterpillars have at least enough abdominal prolegs to spell “sawfly” (so 6 or more prolegs). Bacillus thuringiensis Kurstaki does not manage sawflies.

Bagworm: Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis is a native species of moth whose larvae construct bag-like coverings over themselves with host plant leaves and twigs. This insect overwinters in the egg stage, within the bags of deceased females from last season. Eggs may hatch and young larvae are observed feeding around mid-June, or roughly between 600-900 GDD’s. Remove and destroy overwintering bags before June. In certain areas across MA in 2019, increased populations of bagworms were observed and reported. At this time, bagworm caterpillars are large (hidden within their bags made of chewed leaves and other debris) and capable of completely defoliating young trees. Bagworm caterpillars were reported feeding on honeylocust in Holyoke, MA on 7/22/20. See photos of bagworms at the base of a defoliated tree, as reported by Sarah Greenleaf, MA DCR Urban Forester.More information can be found here:https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/bagworm

Bagworm: Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis is a native species of moth whose larvae construct bag-like coverings over themselves with host plant leaves and twigs. This insect overwinters in the egg stage, within the bags of deceased females from last season. Eggs may hatch and young larvae are observed feeding around mid-June, or roughly between 600-900 GDD’s. Remove and destroy overwintering bags before June. In certain areas across MA in 2019, increased populations of bagworms were observed and reported. At this time, bagworm caterpillars are large (hidden within their bags made of chewed leaves and other debris) and capable of completely defoliating young trees. Bagworm caterpillars were reported feeding on honeylocust in Holyoke, MA on 7/22/20. See photos of bagworms at the base of a defoliated tree, as reported by Sarah Greenleaf, MA DCR Urban Forester.More information can be found here:https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/bagworm- Dogwood Borer: Synanthedon scitula is a species of clearwing moth whose larvae bore not only into dogwood (Cornus), but hosts also include flowering cherry, chestnut, apple, mountain ash, hickory, pecan, willow, birch, bayberry, oak, hazel, myrtle, and others. Kousa dogwood appear to be resistant to this species. Signs include the sloughing of loose bark, brown frass, particularly near bark cracks and wounds, dead branches, and adventitious growth. The timing of adult emergence can be expected when dogwood flower petals are dropping and weigela begins to bloom. Adult moth flights continue from then until September. Emergence in some hosts (ex. apple) appears to be delayed, but this differs depending upon the location in this insect’s range. Eggs are laid singly, or in small groups, on smooth and rough bark. Female moths preferentially lay eggs near wounded bark. After hatch, larvae wander until they find a suitable entrance point into the bark. This includes wounds, scars, or branch crotches. This insect may also be found in twig galls caused by other insects or fungi. Larvae feed on phloem and cambium. Fully grown larvae are white with a light brown head and approx. ½ inch long. Pheromone traps and lures are useful for determining the timing of adult moth emergence and subsequent management.

Emerald Ash Borer: (Agrilus planipennis, EAB) As of July 27, 2020, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation has confirmed a total of at least 127 communities in Massachusetts that have known populations of emerald ash borer. An updated map of these locations across the state may be found here: https://ag.umass.edu/fact-sheets/emerald-ash-borer .

Emerald Ash Borer: (Agrilus planipennis, EAB) As of July 27, 2020, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation has confirmed a total of at least 127 communities in Massachusetts that have known populations of emerald ash borer. An updated map of these locations across the state may be found here: https://ag.umass.edu/fact-sheets/emerald-ash-borer .

This wood-boring beetle readily attacks ash (Fraxinus spp.) including white, green, and black ash and has also been found developing in white fringe tree (Chionanthus virginicus) and has been reported in cultivated olive (Olea europaea). Adult insects of this species will not be present at this time of year. Signs of an EAB infested tree may include (at this time) D-shaped exit holes in the bark (from adult emergence in previous years), “blonding” or lighter coloration of the ash bark from woodpecker feeding (chipping away of the bark as they search for larvae beneath), and serpentine galleries visible through splits in the bark, from larval feeding beneath. Positive identification of an EAB-infested tree may not be possible with these signs individually on their own.

For further information about this insect, please visit: https://ag.umass.edu/fact-sheets/emerald-ash-borer . If you believe you have located EAB-infested ash trees, particularly in an area of Massachusetts not identified on the map provided, please report here: http://massnrc.org/pests/pestreports.htm .

- Fall Home-Invading Insects: Various insects, such as ladybugs, boxelder bugs, seedbugs, and stink bugs will begin to seek overwintering shelters in warm places, such as homes, throughout the next couple of months. While such invaders do not cause any measurable structural damage, they can become a nuisance especially when they are present in large numbers. While the invasion has not yet begun, if you are not willing to share your home with such insects, now should be the time to repair torn window screens, repair gaps around windows and doors, and sure up any other gaps through which they might enter the home.

Fall Webworm: Hyphantria cunea is native to North America and Mexico. It is now considered a world-wide pest, as it has spread throughout much of Europe and Asia. (For example, it was introduced accidentally into Hungary from North America in the 1940’s.) Hosts include nearly all shade, fruit, and ornamental trees except conifers. In the USA, at least 88 species of trees are hosts for these insects, while in Europe at least 230 species are impacted. In the past history of this pest, it was once thought that the fall webworm was a two-species complex. It is now thought that H. cunea has two color morphs – one black headed and one red headed. These two color forms differ not only in the coloration of the caterpillars and the adults, but also in their behaviors. Caterpillars may go through at least 11 molts, each stage occurring within a silken web they produce over the host. When alarmed, all caterpillars in the group will move in unison in jerking motions that may be a mechanism for self-defense. Depending upon the location and climate, 1-4 generations of fall webworm can occur per year. Fall webworm adult moths lay eggs on the underside of the leaves of host plants in the spring. These eggs hatch in late June or early July depending on climate. Fall webworm caterpillars were observed feeding on foliage coated in webbing on 7/8/2020 and 7/21/2020 in Chesterfield, MA. Branches fed upon by this insect have web-coated leaves that have now turned brown. Young larvae feed together in groups on the undersides of leaves, first skeletonizing the leaf and then enveloping other leaves and eventually entire branches within their webs. Webs are typically found on the terminal ends of branches. All caterpillar activity occurs within this tent, which becomes filled with leaf fragments, cast skins, and frass. Fully grown larvae then wander from the webs and pupate in protected areas such as the leaf litter where they will remain for the winter. Adult fall webworm moths emerge the following spring/early summer to start the cycle over again. 50+ species of parasites and 36+ species of predators are known to attack fall webworm in North America. Fall webworms typically do not cause extensive damage to their hosts. Nests may be an aesthetic issue for some. If in reach, small fall webworm webs may be pruned out of trees and shrubs and destroyed. Do not set fire to H. cunea webs when they are still attached to the host plant.

Fall Webworm: Hyphantria cunea is native to North America and Mexico. It is now considered a world-wide pest, as it has spread throughout much of Europe and Asia. (For example, it was introduced accidentally into Hungary from North America in the 1940’s.) Hosts include nearly all shade, fruit, and ornamental trees except conifers. In the USA, at least 88 species of trees are hosts for these insects, while in Europe at least 230 species are impacted. In the past history of this pest, it was once thought that the fall webworm was a two-species complex. It is now thought that H. cunea has two color morphs – one black headed and one red headed. These two color forms differ not only in the coloration of the caterpillars and the adults, but also in their behaviors. Caterpillars may go through at least 11 molts, each stage occurring within a silken web they produce over the host. When alarmed, all caterpillars in the group will move in unison in jerking motions that may be a mechanism for self-defense. Depending upon the location and climate, 1-4 generations of fall webworm can occur per year. Fall webworm adult moths lay eggs on the underside of the leaves of host plants in the spring. These eggs hatch in late June or early July depending on climate. Fall webworm caterpillars were observed feeding on foliage coated in webbing on 7/8/2020 and 7/21/2020 in Chesterfield, MA. Branches fed upon by this insect have web-coated leaves that have now turned brown. Young larvae feed together in groups on the undersides of leaves, first skeletonizing the leaf and then enveloping other leaves and eventually entire branches within their webs. Webs are typically found on the terminal ends of branches. All caterpillar activity occurs within this tent, which becomes filled with leaf fragments, cast skins, and frass. Fully grown larvae then wander from the webs and pupate in protected areas such as the leaf litter where they will remain for the winter. Adult fall webworm moths emerge the following spring/early summer to start the cycle over again. 50+ species of parasites and 36+ species of predators are known to attack fall webworm in North America. Fall webworms typically do not cause extensive damage to their hosts. Nests may be an aesthetic issue for some. If in reach, small fall webworm webs may be pruned out of trees and shrubs and destroyed. Do not set fire to H. cunea webs when they are still attached to the host plant.

- Hickory Tussock Moth: Lophocampa caryae is native to southern Canada and the northeastern United States. There is one generation per year. Overwintering occurs as a pupa inside a fuzzy, oval shaped cocoon. Adult moths emerge approximately in May and their presence can continue into July. Females will lay clusters of 100+ eggs together on the underside of leaves. Females of this species can fly, however they have been called weak fliers due to their large size. When first hatched from their eggs, the young caterpillars will feed gregariously in a group, eventually dispersing and heading out on their own to forage. Caterpillar maturity can take up to three months and color changes occur during this time. These caterpillars are essentially white with some black markings and a black head capsule. They are very hairy, and should not be handled with bare hands as many can have skin irritation or rashes (dermatitis) as a result of interacting with hickory tussock moth hairs. By late September, the caterpillars will create their oval, fuzzy cocoons hidden in the leaf litter where they will again overwinter. Hosts whose leaves are fed upon by these caterpillars include but are not limited to hickory, walnut, butternut, linden, apple, basswood, birch, elm, black locust, and aspen. Maple and oak have also been reportedly fed upon by this insect. Several wasp species are parasitoids of hickory tussock moth caterpillars.

- Lacebugs: Stephanitis spp. lacebugs such as S. pyriodes can cause severe injury to azalea foliage. S. rhododendri can be common on Rhododendron and mountain laurel. S. takeyai has been found developing on Japanese Andromeda, Leucothoe, Styrax, and willow. Stephanitis spp. lace bug activity should be monitored through September. Before populations become too large, treat with a summer rate horticultural oil spray as needed. Be sure to target the undersides of the foliage in order to get proper coverage of the insects. Certain azalea and andromeda cultivars may be less preferred by lace bugs.

Magnolia and Tuliptree Scales: The soft scale insects known as the magnolia scale (Neolecanium cornuparvum) and the tuliptree scale (Toumeyella liriodendri) can be difficult to differentiate in the field, depending upon the host they are found on. (On Magnolia, it is very difficult to distinguish between the two species of soft scale.) As two native scale insects in North America, the Magnolia and tuliptree scales are hosts themselves for natural enemies that can impact their populations. Solitary parasitoid larvae have been collected from Magnolia scales and have been identified as a syrphid fly species, Ocyptamus costatus. The natural enemies of the tuliptree scale have been studied to a greater degree and include certain lady beetle species [Hyperaspis signata, Adalia (formerly Hyperaspis) bipunctata, and Chilocorus stigma] which feed on nymphal scales, a number of parasitic wasps, and even an insect feeding moth caterpillar (Laetilia coccidivora). This particular moth species, also referred to as a type of snout moth, will consume the tuliptree scale underneath the protection of a silken web it spins over them! (The specific epithet coccidivora can be translated as “ones that eat soft scales” or Coccidae.) Unfortunately, in a landscape setting, it often seems that although these natural enemies may be common within the scale populations, they are seldom able to reduce the scale insect numbers below damaging levels. That being said, our management options should still seek to preserve these natural enemies.

Magnolia and Tuliptree Scales: The soft scale insects known as the magnolia scale (Neolecanium cornuparvum) and the tuliptree scale (Toumeyella liriodendri) can be difficult to differentiate in the field, depending upon the host they are found on. (On Magnolia, it is very difficult to distinguish between the two species of soft scale.) As two native scale insects in North America, the Magnolia and tuliptree scales are hosts themselves for natural enemies that can impact their populations. Solitary parasitoid larvae have been collected from Magnolia scales and have been identified as a syrphid fly species, Ocyptamus costatus. The natural enemies of the tuliptree scale have been studied to a greater degree and include certain lady beetle species [Hyperaspis signata, Adalia (formerly Hyperaspis) bipunctata, and Chilocorus stigma] which feed on nymphal scales, a number of parasitic wasps, and even an insect feeding moth caterpillar (Laetilia coccidivora). This particular moth species, also referred to as a type of snout moth, will consume the tuliptree scale underneath the protection of a silken web it spins over them! (The specific epithet coccidivora can be translated as “ones that eat soft scales” or Coccidae.) Unfortunately, in a landscape setting, it often seems that although these natural enemies may be common within the scale populations, they are seldom able to reduce the scale insect numbers below damaging levels. That being said, our management options should still seek to preserve these natural enemies.

The Magnolia scale is distributed throughout the eastern United States. The tuliptree scale is found east of the Mississippi River from Michigan to Alabama and from New York and Connecticut to Florida. It is also reported to be found in ornamental tuliptrees and Magnolias in California and could be found wherever these trees are grown. Magnolia scale host plants include: Magnolia stellata (star Magnolia), M. acuminata (cucumber Magnolia), M. lilliflora ‘Nigra’ (lily Magnolia; formerly M. quinquepeta), and M. soulangeana (Chinese Magnolia). Other species may be hosts for this scale, but attacked to a lesser degree. M. grandiflora (southern Magnolia) may be such an example. Tuliptree scale host plants include: Liriodendron tulipifera (tuliptree or yellow poplar), Magnolia stellata (star Magnolia), and M. soulangeana (Chinese Magnolia). This insect has also been recorded on M. grandiflora (southern Magnolia) and Tilia spp. (linden). The tuliptree scale has also, to a lesser extent, been reported on other ornamental trees and shrubs.

Mature individuals settle on a location on branches and twigs, then insert piercing-sucking mouthparts to feed. The insects feed on plant fluids and excrete large amounts of a sugary substance known as honeydew. Sooty mold, often black in color, will then grow on the honeydew that has coated branches and leaves. Repeated, heavy infestations can result in branch dieback and at times, death of the plant. Honeydew may also be very attractive to ants, wasps, and hornets. The life cycle of both of these species is similar and may have similar timing during the year, however subtle differences exist. The life cycle of the magnolia scale is as follows: This scale overwinters as a young nymph (immature stage) which is elliptical in shape, mostly a dark-slate gray, except for a median ridge that is red/brown in color. These overwintering nymphs may be found on the undersides of 1st and 2nd year old twigs. The first molt (shedding of the exoskeleton to allow growth) can occur by late April or May in parts of this insect’s range and the second molt will occur in early June. At that time, the immature scales have turned a deep purple color. Stems of the host plant may appear purple in color and thickened – but this is a coating of nymphal Magnolia scales, not the stem itself. Eventually, these immature scales secrete a white layer of wax over their bodies, looking as if they have been rolled in powdered sugar. By August, the adult female scale is fully developed, elliptical and convex in shape and ranging from a pinkish-orange to a dark brown color. Adult females may also be covered in a white, waxy coating. By that time, the females produce nymphs (living young; eggs are not “laid”) that wander the host before settling on the newest twigs to overwinter. In the Northeastern United States, this scale insect has a single generation per year.

The lifecycle of the tuliptree scale is as follows: The mature female tuliptree scale is hemispherical in shape. The color of the mature female varies in this species as well - a grayish-green to pink-orange insect mottled with black. Adult males emerge sometime in June and mate with the females. Like the Magnolia scale, eggs develop within the body of the female tuliptree scale, leading to the “live birth” of immatures (crawlers) in late August and September. In the Northeast, one generation of tuliptree scales occurs per year. (However, in the southern-most portions of its range, this insect has been found in all stages of development during the winter, suggesting multiple generations per year.) A single female tuliptree scale may produce 3,000+ crawlers in one season. These crawlers are tiny (approximately the size of the head of a pin) and settle on host plant twigs in September. Past studies have shown that in addition to moving on their own with fully functional legs, the crawlers can be blown to new hosts on the wind, up to 100 feet away. (Being wind-blown to a new host, however, is a haphazard method of travel through which some less than 20% of these crawlers successfully make contact with a host plant, and fewer still attach to a suitable site on the plant.) The immature, crawler stage molts once prior to overwintering.

Spotted Lanternfly: (Lycorma delicatula, SLF) is not known to occur in Massachusetts landscapes (no established populations are known in MA at this time). However, due to the great ability of this insect to hitchhike using human-aided movement, it is important that we remain vigilant in Massachusetts and report any suspicious findings. Spotted lanternfly reports can be sent here:https://massnrc.org/pests/slfreport.aspx

Spotted Lanternfly: (Lycorma delicatula, SLF) is not known to occur in Massachusetts landscapes (no established populations are known in MA at this time). However, due to the great ability of this insect to hitchhike using human-aided movement, it is important that we remain vigilant in Massachusetts and report any suspicious findings. Spotted lanternfly reports can be sent here:https://massnrc.org/pests/slfreport.aspx

For a map of known, established populations of SLF as well as detections outside of these areas where individual finds of spotted lanternfly have occurred (but no infestations are present), visit: https://nysipm.cornell.edu/environment/invasive-species-exotic-pests/spotted-lanternfly/ This map depicts an individual find of spotted lanternfly at a private residence in Boston, MA that was reported by the MA Department of Agricultural Resources on February 21, 2019. More information about this detection in Boston, where no established infestation was found, is provided here: https://www.mass.gov/news/state-agricultural-officials-urge-residents-to-check-plants-for-spotted-lanternfly

This insect is a member of the Order Hemiptera (true bugs, cicadas, hoppers, aphids, and others) and the Family Fulgoridae, also known as planthoppers. The spotted lanternfly is a non-native species first detected in the United States in Berks County, Pennsylvania and confirmed on September 22, 2014.

The spotted lanternfly is considered native to China, India, and Vietnam. It has been introduced as a non-native insect to South Korea and Japan, prior to its detection in the United States. In South Korea, it is considered invasive and a pest of grapes and peaches. The spotted lanternfly has been reported from over 70 species of plants, including the following: tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) (preferred host), apple (Malus spp.), plum, cherry, peach, apricot (Prunus spp.), grape (Vitis spp.), pine (Pinus spp.), pignut hickory (Carya glabra), sassafras (Sassafras albidum), serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.), slippery elm (Ulmus rubra), tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera), white ash (Fraxinus americana), willow (Salix spp.), American beech (Fagus grandifolia), American linden (Tilia americana), American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis), big-toothed aspen (Populus grandidentata), black birch (Betula lenta), black cherry (Prunus serotina), black gum (Nyssa sylvatica), black walnut (Juglans nigra), dogwood (Cornus spp.), Japanese snowbell (Styrax japonicus), maple (Acer spp.), oak (Quercus spp.), and paper birch (Betula papyrifera).

The adults and immatures of this species damage host plants by feeding on sap from stems, leaves, and the trunks of trees. In the springtime in Pennsylvania (late April - mid-May) nymphs (immatures) are found on smaller plants and vines and new growth of trees and shrubs. Third and fourth instar nymphs migrate to the tree of heaven and are observed feeding on trunks and branches. Trees may be found with sap weeping from the wounds caused by the insect’s feeding. The sugary secretions (excrement) created by this insect may coat the host plant, later leading to the growth of sooty mold. Insects such as wasps, hornets, bees, and ants may also be attracted to the sugary waste created by the lanternflies, or sap weeping from open wounds in the host plant. Host plants have been described as giving off a fermented odor when this insect is present.

Adults are present by the middle of July in Pennsylvania and begin laying eggs by late September and continue laying eggs through late November and even early December in that state. Adults may be found on the trunks of trees such as the tree of heaven or other host plants growing in close proximity to them. Egg masses of this insect are gray in color and look similar in some ways to gypsy moth egg masses.

Host plants, bricks, stone, lawn furniture, recreational vehicles, and other smooth surfaces can be inspected for egg masses. Egg masses laid on outdoor residential items such as those listed above may pose the greatest threat for spreading this insect via human aided movement.

For more information about the spotted lanternfly, visit this fact sheet: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/spotted-lanternfly .

- Tuliptree Aphid: Illinoia liriodendri is a species of aphid associated with the tuliptree, wherever it is grown. Depending upon local temperatures, these aphids may be present from mid-June through early fall. Large populations can develop by late summer. Some leaves, especially those in the outer canopy, may turn brown or yellow and drop from infested trees prematurely. The most significant impact these aphids can have is typically the resulting honeydew, or sugary excrement, which may be present in excessive amounts and coat leaves and branches, leading to sooty mold growth. This honeydew may also make a mess of anything beneath the tree. Wingless adults are approximately 1/8 inch in length, oval, and can range in color from pale green to yellow. There are several generations per year. This is a native insect. Management is typically not necessary, as this insect does not significantly impact the overall health of its host. Tuliptree aphids also have plenty of natural enemies, such as ladybeetles and parasites.