UMass Extension's Landscape Message is an educational newsletter intended to inform and guide Massachusetts Green Industry professionals in the management of our collective landscape. Detailed reports from scouts and Extension specialists on growing conditions, pest activity, and cultural practices for the management of woody ornamentals, trees, and turf are regular features. The following issue has been updated to provide timely management information and the latest regional news and environmental data.

Thanks for your continuing interest! Note that we are now in the every-other-week period of the season, and the next message will be posted on September 8. To receive immediate notification when the next Landscape Message update is posted, be sure to join our e-mail list

To read individual sections of the message, click on the section headings below to expand the content:

Scouting Information by Region

Environmental Data

The following data was collected on or about August 23, 2023. Total accumulated growing degree days (GDD) represent the heating units above a 50ºF baseline temperature collected via regional NEWA stations (http://newa.cornell.edu) for the 2023 calendar year. This information is intended for use as a guide for monitoring the developmental stages of pests in your location and planning management strategies accordingly.

|

MA Region/Location |

2023 Growing Degree Days |

Soil Temp |

Precipitation |

Time/Date of Readings |

||

| Gain since last report |

2023 total |

Sun |

Shade |

|||

|

CAPE |

291 |

1929 |

72 |

68 |

1.81 |

8/23/2023 12:00 PM |

|

SOUTHEAST |

290 |

1964 |

76 |

66 |

3.25 |

8/23/2023 3:00 PM |

|

NORTH SHORE |

243 |

1815 |

66 |

62 |

1.76 |

8/23/2023 9:30 AM |

|

EAST |

292 |

2087 |

72 |

67 |

1.71 |

8/23/2023 4:00 PM |

|

METRO |

269 |

1922 |

64 |

62 |

2.48 |

8/23/2023 5:45 AM |

|

CENTRAL |

270 |

1988 |

66 |

64 |

3.76 |

8/23/2023 4:30 PM |

|

PIONEER VALLEY |

270 |

2038 |

69 |

65 |

2.77 |

8/23/2023 12:00 PM |

|

BERKSHIRES |

237 |

1702 |

69 |

62 |

2.31 |

8/23/2023 6:30 AM |

|

AVERAGE |

270 |

1931 |

69 |

65 |

2.48 |

- |

|

n/a = information not available |

||||||

US Drought Monitor: No drought areas are currently designated in the state of Massachusetts. State map as of Thursday 8/24: https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?MA

Phenology

| Indicator Plants - Stages of Flowering (BEGIN, BEGIN/FULL, FULL, FULL/END, END) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLANT NAME (Botanic / Common) | CAPE | S.E. | N.S. | EAST | METRO W. | CENT. | P.V. | BERK. |

| Heptacodium miconioides (seven son flower) | Begin | * | * | * | * | Begin | Begin | * |

| Clematis terniflora (sweet autumn clematis) | Begin | * | Begin/Full | * | * | * | Begin/Full | Begin |

| Polygonum cuspidatum / Reynoutria japonica / Fallopia japonica (Japanese knotweed) | Begin/Full | Full | Begin/ Full | Begin | Begin | * | Begin/Full | * |

| Clethra alnifolia (summersweet clethra) | Full/End | Full/End | Full/End | Full/End | Full | Full/End | End | Full/End |

| Hibiscus syriacus (rose-of-Sharon) | Full/End | Full/End | Full/ End | Full/End | Full/End | Full/End | Full/End | Full/End |

| * = no activity to report/information not available | ||||||||

Regional Notes

Cape Cod Region (Barnstable)

General Conditions:

The average temperature for the period from August 9 to August 23 was 71°F with a high of 86°F on August 21 and a low of 53°F on August 23. Daytime highs have hovered around 80°F for much of the period with nighttime lows in the upper 60s with a few exceptions. The period from August 15–18 was slightly cooler and cloudy. Precipitation fell on several days during the period for a total of just under 2 inches. Soil moisture is adequate and precipitation has exceeded evapotranspiration rates. The conditions are good for fall lawn renovation heading into the end of the month.

Herbaceous plants seen in bloom during the period include purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), black eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta), garden phlox (Phlox paniculata), Joe-Pye weed (Eutrochium maculatum), and some goldenrods (Solidago spp.). Woody plants observed in bloom during the period include mimosa (Albizia julibrissin), hydrangeas (H. macrophylla & H. paniculata), glorybower (Clerodendrum trichotomum), and crape myrtle (Lagerstroemia indica).

Pests/Problems:

Emerald ash borer was confirmed from a street tree in Falmouth. Ash is uncommon on the Cape and the majority are street trees or an occasional landscape or park tree.

Box tree moth was confirmed on Cape Cod recently. Box tree moth is an introduced pest that feeds on boxwood and can cause extensive damage. Check boxwoods and see this fact sheet https://www.aphis.usda.gov/publications/plant_health/alert-box-tree-moth.pdf for symptoms and signs. Report infestations in Massachusetts to the MA Introduced Pest Outreach Project at https://www.massnrc.org/pests/report.aspx.

Southern pine beetle (SPB) has been found in traps for several years in MA and was recently confirmed causing mortality in a 13 acre stand of pitch pine on Nantucket. SPB is an important forest pest of pitch pine, one of the Cape’s dominant tree species - keep an eye for this important pest. Also, keep on the lookout for spotted lanternfly (SLF), another introduced pest. The primary host is tree of heaven, but SLF is capable of feeding on numerous other species. Suspected detections in Massachusetts should also be reported to the MA Introduced Pest Outreach Project at https://www.massnrc.org/pests/report.aspx.

Other insects or insect injury observed during this period includes turpentine beetle and pine tip moth damage to pitch pine, pine tip weevil damage to white pine, black oak gall wasp damage on black oak, defoliation from dogwood sawfly larvae on alternate leaf dogwood, chilli thrips damage on bigleaf hydrangea, lacewing damage on andromeda and azalea, broad mite damage on summersweet, and hibiscus sawfly damage on hardy hibiscus.

Disease symptoms and signs observed during this period include: beech leaf disease (BLD) on American and European beech; shot hole disease on purple leaf plum; foliar nematode on hosta; Cercospora leaf spot on bigleaf hydrangea; boxwood blight on boxwood; basil downy mildew on basil; Guignardia leaf blotch on horsechestnut; cedar apple rust, apple scab and fire blight on crabapple; oak anthracnose on white oak; pear trellis rust on callery pear; Phytophthora root rot on lavender and smooth hydrangea; fungal tip blight on Leyland cypress; shoot flagging on oak likely Botryosphaeria; grey leaf spot on Japanese forest grass; and powdery mildew on many herbaceous and woody plants.

Now is a good time to ID jumping worms in the landscape. Jumping worms reach maturity during the late summer, at which time the white clitellum becomes distinct; the clitellum is 14-16 segments from the head. For more details, see these UMass Extension fact sheets.

Slug and snail damage was observed on several herbaceous plants.

Weeds in bloom include spotted spurge (Euphorbia maculata), purslane (Portulaca oleracea), common tansy (Tanectum vulgare), redroot pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus), lambsquarters (Chenopodium album), Pennsylvania smartweed (Polygonum pensylvanicum), and knapweed (Centaurea maculosa).

Southeast Region (Dighton)

General Conditions:

The weather has transitioned into a late summer pattern of warm days and cool nights, with passing showers, over the past two weeks. The high temperature was 86°F on Monday, August 21. The low was 55°F on Saturday the 12th. The average temperature was 70°F. Generous and frequent showers brought 3.25 inches of rain. The highest winds were 18 mph on Friday, August 18.

Plants in flower: Buddleia davidii (butterfly bush), Campsis radicans (trumpet vine), Clethra alnifolia (summersweet), Hibiscus syriacus (rose-of-Sharon), Hydrangea paniculata (panicle hydrangea), Lythrum salicaria (purple loosestrife), Polygonum cuspidatum (Japanese knotweed), Sophora japonica (Japanese pagoda tree).

Pests/Problems

Mildew on grapes caused extensive losses in this year's crop. Chinch bugs are being commonly found on lawns. Yellow nutsedge is in flower.

North Shore (Beverly)

General Conditions:

The conditions during this past two-week reporting period were variable. Several days in the first half of the period were hot and humid, with day temperatures in the low to mid 80s and night temperatures in the low to mid 70s. The rest of the period was pleasant with day temperatures in the low to mid 70s and night temperatures in the low to mid 60s. Most of the days had sunny skies, but there were some cloudy days with rain showers. The average daily temperature was 70℉ with the maximum temperature of 85℉ recorded on August 13 and the minimum temperature of 50℉ recorded on August 23. Approximately 1.76 inches of rainfall was recorded at Long Hill during the last two weeks. Woody plants seen in bloom include: silk tree or mimosa (Albizia julibrissin), panicle hydrangea (Hydrangea paniculata), rose-of-Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus), daphne (Daphne spp.), Chinese pearbloom (Poliothyrsis sinensis), and summersweet clethra (Clethra alnifolia). Herbaceous plants seen in bloom include: Culver’s root (Veronicastrum virginicum), anemone (Anemonopsis macrophylla), beebalm (Monarda didyma), shasta daisy (Leucanthemum x superbum), garden phlox (Phlox paniculata), Joe-Pye weed (Eutrochium maculatum), cranesbill (Geranium spp.), summer flowering roses (Rosa spp.), clematis vines (Clematis terniflora), hardy begonia (Begonia grandis), black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta), purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), coral bells (Heuchera sp.). and an assortment of summer annual plants.

Pests/Problems:

Deer browsing and rabbit damage was observed on some perennial plants. Powdery mildew continues to be observed on garden phlox, monarda and lilacs. Weeds continue to thrive in landscapes. Some of the weeds observed in bloom include: white clover (Trifolium repens), yellow woodsorrel (Oxalis stricta), purslane (Portulaca oleracea), spotted spurge (Euphorbia maculata), bittersweet nightshade (Solanum dulcamara), Japanese knotweed (Polygonum cuspidatum), pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus), ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia), and goldenrod (Solidago spp). Ticks and mosquitoes continue to be very active. Always protect yourself when working or walking outdoors in the woods.

East (Boston)

General Conditions: We have experienced moderate conditions over the past two weeks. Daytime high temperatures averaged 80°F with overnight lows averaging 64°F. We received precipitation on seven of the previous 14 days totaling 1.71 inches. Severe weather warnings were issued on August 18th, we received .71 inches of precipitation; several tornadoes touched down in neighboring communities. Landscape plants continue to put on growth.

Pests/Problems: Many landscape soils are saturated. Powdery mildew continues to be prevalent on Monarda spp. (bee balm), Phlox paniculata (garden phlox), and Syringa spp. (lilac). There is an abundance of leaf spot throughout the landscape, seemingly on everything. Hibiscus sawfly larvae (Atomacera decepta) continue to feed on hardy hibiscus foliage. Black swallow-wort (Cynanchum louiseae) is forming seed pods. Japanese knotweed (Polygonum cuspidatum) is beginning to flower.

Metro West (Acton)

General Conditions:

The summer season is winding down, with the Labor Day holiday just around the corner. The length of daylight is shortening daily by several minutes and temperatures are cooling off. On the 23rd, the daytime length was at 13:35 minutes with sunrise at 5:59 am and sunset at 7:34 pm To put that into perspective, the previous day’s length of daylight was measured at 13:38 minutes. The high and low temperature recorded for this 2-week reporting period was 86°F on the 13th and 57°F on the 19th. The historical monthly average rainfall for August is 3.72” and as of the 22nd, the total rainfall recorded for the month has been 6.90”. One rain event on the 18th provided much of that rain with 2.13” recorded. This is now the third month in a row where precipitation has exceeded its historical monthly average. Needless to say, soils are well saturated and ready for planting. Plants are heavy with fruit, seed, berries, and nuts.

Pests/Problems:

Plants are heavy with fruit, seed, berries, and nuts, including two unwanted guests found growing in our landscape - Ailanthus altissima (tree of heaven), an invasive tree that is now highly visible and showy because its seeds (samaras) are reddish in color, are plentiful and grow in large clusters, and, not as obvious but in seed, Cynanchum louiseae (black swallow-wort), an herbaceous perennial vine with seed similar to milkweed that can spread far and wide and quickly take over.

Central Region (Boylston)

General Conditions:

During this reporting period in central Massachusetts, the weather has become milder as we enter late summer. The maximum ambient temperature was 86.5°F on 8/13. We have yet to experience temperatures lower than 50 degrees Fahrenheit at night. The average daily temperatures fluctuated between 63.4 and 75.9°F. Total precipitation was significant at 3.76”, which isn’t unusual considering how wet this year has been. During two rain events on 8/15 and 8/18, 1.19” and 1.14” precipitation fell respectively. The latter rain event was accompanied by thunderstorms and, shockingly, lightning that struck one of our buildings. Relative humidity has lessened and the days are feeling less muggy. Weed pressure isn’t as high as it was in June and July. The late summer and early fall bloomers like Solidago spp. (goldenrod), Eupatorium spp. (Joe Pye weed), Symphyotrichum spp. (aster), and Ceratostigma plumbaginoides (leadwort) are capturing our attention. A few of our garden plants, including cultivars of Hamamelis and Itea virginica (Virginia sweetspire), are beginning to show partial fall color. It’s possible that this coloration is due to the inundation we’ve experienced this growing season. Otherwise, the days are becoming shorter and the temperatures cooler with less humidity.

Pests/Problems:

Aphids have been observed on species of Asclepias and Eupatorium. Jumping worms have become a bigger problem this year. They have depleted pockets of our soil by creating fertility and structural problems. Sawfly damage has been observed on Hibiscus. Scale has been observed on a few of our Magnolia species. These pests are more of a nuisance than a serious threat, but they can negatively impact the aesthetics of our spaces. Lastly, Lythrum salicaria (purple loosestrife), however, has been popping up in odd places here and there. Due to the saturated soils and frequent rain, the seeds have seemed to find homes in unsuspected locations.

Pioneer Valley (Amherst)

General Conditions:

Late summer is flourishing across the Pioneer Valley as the autumn season unofficially starts following the Labor Day weekend. We’ve had some downright pleasant temperatures in recent days with highs in the upper 70s to low 80s and cool nights in the 50s. The oppressive heat and mugginess of mid-summer is in the past and the landscape is still vibrant with color. For many trees and shrubs, this has been a banner growing season with the (over) abundance of rain. New shoot and leaf development was recently observed on eastern hemlock, eastern larch, pin oak, redbud, and red maple across the UMass campus. When deciduous trees are still flushing new growth in mid-August, it’s been a good year. Conifers like false-cypress, arborvitae, and juniper often have a late season flush and this year it’s far more noticeable. Turfgrasses and lawn weeds are still growing at a rapid pace and remain healthy and green. Early leaf color and drop is also occurring on scattered trees across the landscape. September conditions will play a significant role in the quality of the fall foliage. Bright, sunny days and cool nights during our ninth month help to stimulate production of anthocyanins that produce brilliant reds and expose the carotenoids that produce the oranges and yellows as chlorophyll production wanes. Soil moisture remains plentiful and late August through early September is an excellent time to transplant conifers. New root development in the fall will help them better establish the following growing season. The appearance of red maple seedlings has finally slowed down after what was undeniably a mast year for this species. Many sugar maple canopies are loaded with mature seed that will soon be falling. This is a good time of year to gently excavate the root flare on young trees that were transplanted within the past five years (or so) to prune out any adventitious roots that may be problematic over time. With the abundance of rain this season, mulch and other organic matter may have washed over the root flare, allowing for the development of future circling and girdling roots. Groundcovers or perennials established at the base of the tree can also result in the flare being covered. The nighttime soundscape remains very active with katydids and crickets.

Pests/Problems:

Apple and crabapple defoliation due to apple scab continues with some trees nearly defoliated. Pseudocercospora leaf blotch is widespread on lilacs (Syringa vulgaris) throughout the area. Infected plants have brown-colored spots and blotches that can advance to a blight of the foliage and premature shedding (see Disease section below). Lilacs are extremely hardy plants and these infections will likely result in only minor reductions in growth and/or flowering next season. However, remove and discard infected foliage from the base of the plants this autumn season to reduce overwintering inoculum. The abundance of rainfall this season is likely to blame for this significant outbreak. Slime molds and mulch-inhabiting fungi have been very common this season. Slime mold growth around the base of trees and shrubs can be alarming for some but these organisms do not parasitize plants. Tubakia leaf blotch is very conspicuous on scattered oaks in the landscape right now. Infections often take place in the spring but symptoms appear much later in the growing season. Currently, it appears as reddish-brown circular spots that coalesce to create larger, necrotic blotches. The disease is primarily a concern for members of the red oak group but white oaks are also susceptible. Scattered feeding damage by grasshoppers is present on hardwoods and conifers. Slugs are still very abundant on leafy perennials. It’s not too late to treat lace bug infestations on azalea, rhododendron, and Andromeda.

Berkshire Region (West Stockbridge)

General conditions:

While rains persisted over the past 2-week scouting period, the rainfall amounts were not as heavy as have been experienced through much of the year. Totals from August 9-23 for the three NEWA sites in the county were: 2.07 inches in North Adams, 2.30 inches in Pittsfield, and 2.06 inches for Richmond. At this site in West Stockbridge, 2.31 inches were collected. Currently, soils are moist and still warm, and air temperatures are slowly dropping, thus creating ideal conditions for late season planting of herbaceous perennials and woody plants. Day time temperatures are now mostly in the 70s and night temperatures in the low 50s or upper 40s. Landscapes are flush with color from late summer flowering plants. Turfgrass growth is rapid and lush. It’s almost time for an application of fertilizer for fertilized lawns. Even if no more than a single lawn fertilizer application is made, research has shown that this is the ideal time for that application.

Pests/Problems:

Generally, insect pest problems have diminished. A few Japanese beetles are hanging around as are a few adult lily leaf beetles, but the numbers are low. However, many plants have experienced skeletonized leaves resulting from feeding by Japanese beetles. This could impact carbohydrate storage and weaken growth of some plants next year. The number of white ash trees that are dead or visibly in decline due to invasion by emerald ash borers is steadily increasing and, at least in this area of the state, fewer and fewer white ash remain healthy. Snail and slug populations remain high due to persistent moist conditions from rains and heavy dew. The moisture this summer has resulted in considerable leaf spot infections as well as powdery mildew now at their peak. This could account for some premature color change in foliage now seen at some sites. Among the foliar diseases is cedar apple rust. It has left many ornamental crabapples only sparsely foliated. A check of the undersides of the remaining crabapple leaves will show hair-like projections from the rust spots. These projections, called aecia, release spores (aeciaspores) which will infect the alternate host of this disease, i.e., Juniperus spp. While we are far removed from the heavy frost/freeze of last May 18, a few plants are still showing the effects. Notably among these is copper beech, especially younger specimens or those routinely pruned for a hedge. Many of the twigs at the top of these specimens have produced no new growth or just a few leaves. Though the plants survive, they may be mis-shaped. Deer activity has picked up as the fawns are approaching maturity and their appetite is peaking. Complaints of browsing on ornamental and young woody plants are as plentiful as the deer population.

Generally, insect pest problems have diminished. A few Japanese beetles are hanging around as are a few adult lily leaf beetles, but the numbers are low. However, many plants have experienced skeletonized leaves resulting from feeding by Japanese beetles. This could impact carbohydrate storage and weaken growth of some plants next year. The number of white ash trees that are dead or visibly in decline due to invasion by emerald ash borers is steadily increasing and, at least in this area of the state, fewer and fewer white ash remain healthy. Snail and slug populations remain high due to persistent moist conditions from rains and heavy dew. The moisture this summer has resulted in considerable leaf spot infections as well as powdery mildew now at their peak. This could account for some premature color change in foliage now seen at some sites. Among the foliar diseases is cedar apple rust. It has left many ornamental crabapples only sparsely foliated. A check of the undersides of the remaining crabapple leaves will show hair-like projections from the rust spots. These projections, called aecia, release spores (aeciaspores) which will infect the alternate host of this disease, i.e., Juniperus spp. While we are far removed from the heavy frost/freeze of last May 18, a few plants are still showing the effects. Notably among these is copper beech, especially younger specimens or those routinely pruned for a hedge. Many of the twigs at the top of these specimens have produced no new growth or just a few leaves. Though the plants survive, they may be mis-shaped. Deer activity has picked up as the fawns are approaching maturity and their appetite is peaking. Complaints of browsing on ornamental and young woody plants are as plentiful as the deer population.

Regional Scouting Credits

- CAPE COD REGION - Russell Norton, Horticulture and Agriculture Educator with Cape Cod Cooperative Extension, reporting from Barnstable.

- SOUTHEAST REGION - Brian McMahon, Arborist, reporting from the Dighton area.

- NORTH SHORE REGION - Geoffrey Njue, Green Industry Specialist, UMass Extension, reporting from the Long Hill Reservation, Beverly.

- EAST REGION - Kit Ganshaw & Sue Pfeiffer, Horticulturists reporting from the Boston area.

- METRO WEST REGION – Julie Coop, Forester, Massachusetts Department of Conservation & Recreation, reporting from Acton.

- CENTRAL REGION - Mark Richardson, Director of Horticulture reporting from New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill, Boylston.

- PIONEER VALLEY REGION - Nick Brazee, Plant Pathologist, UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab, reporting from Amherst.

- BERKSHIRE REGION - Ron Kujawski, Horticultural Consultant, reporting from Great Barrington.

Woody Ornamentals

Diseases

Recent pests, pathogens, or problems of interest seen in the UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab, a select few:

Black spot anthracnose of slippery elm (Ulmus rubra) caused by Gnomonia ulmea. Elm anthracnose can be locally abundant during wet summers such as this one. The symptoms and signs typically appear as small, circular, masses of fungal tissue with yellow-orange margins. These spots are often numerous and scattered across the entire leaf surface. Leaf yellowing and premature shedding from elm anthracnose can mimic the symptoms of Dutch elm disease, so careful distinction is important for certain trees. On this slippery elm, growing in a shaded environment with good loam soils, instead of small, circular spots there are large and angular areas of necrotic tissue with fungal fruiting bodies surrounded by yellowing leaf tissue. These blotches occur primarily along the midvein and radiate towards the leaf margin.

Black spot anthracnose of slippery elm (Ulmus rubra) caused by Gnomonia ulmea. Elm anthracnose can be locally abundant during wet summers such as this one. The symptoms and signs typically appear as small, circular, masses of fungal tissue with yellow-orange margins. These spots are often numerous and scattered across the entire leaf surface. Leaf yellowing and premature shedding from elm anthracnose can mimic the symptoms of Dutch elm disease, so careful distinction is important for certain trees. On this slippery elm, growing in a shaded environment with good loam soils, instead of small, circular spots there are large and angular areas of necrotic tissue with fungal fruiting bodies surrounded by yellowing leaf tissue. These blotches occur primarily along the midvein and radiate towards the leaf margin.

Pseudocercospora leaf blotch (Pseudocercospora sp.) of common lilac (Syringa vulgaris). Plants are over 50-years-old and have developed into a dense mass with limited air flow. They experience roughly half-sun and have received very little pruning in previous years. Brown-colored spots and blotches, leading to a total collapse of the foliage, was exhibited by the submitted sample. Most of the diseased leaves will be shed but some may remain in the canopy. After incubation, oily spore masses extruded from fruiting bodies produced on the underside (abaxial surface) of the leaf. The symptoms on these particular plants were present in 2022. However, this year the disease is widespread throughout the region, likely promoted by the heavy rainfall much of the Commonwealth has experienced this summer. Diseased foliage should be collected and removed from the site this autumn season to limit the overwintering inoculum that can establish new infections next year. Pruning to improve air flow and light, especially within the interior canopy, can also help to reduce disease pressure in the future.

Pseudocercospora leaf blotch (Pseudocercospora sp.) of common lilac (Syringa vulgaris). Plants are over 50-years-old and have developed into a dense mass with limited air flow. They experience roughly half-sun and have received very little pruning in previous years. Brown-colored spots and blotches, leading to a total collapse of the foliage, was exhibited by the submitted sample. Most of the diseased leaves will be shed but some may remain in the canopy. After incubation, oily spore masses extruded from fruiting bodies produced on the underside (abaxial surface) of the leaf. The symptoms on these particular plants were present in 2022. However, this year the disease is widespread throughout the region, likely promoted by the heavy rainfall much of the Commonwealth has experienced this summer. Diseased foliage should be collected and removed from the site this autumn season to limit the overwintering inoculum that can establish new infections next year. Pruning to improve air flow and light, especially within the interior canopy, can also help to reduce disease pressure in the future.

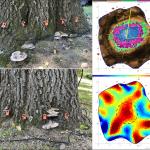

Root and lower trunk rot of a mature black oak (Quercus velutina) on the UMass campus caused by Niveoporofomes spraguei. Luley describes Niveoporofomes as “common; probably more common than is realized because it is not well known by field arborists” (p. 72; Wood Decay Fungi Common to Urban Living Trees in the Northeast and Central United States, 2nd edition). This tree was evaluated for internal decay using sonic and electrical resistance tomography in Sept of 2018, although at the time the pathogen was unknown, as no conks or mushrooms were present. Recently, numerous N. spraguei conks were found growing from the lower trunk and root flare, close to the soil line. Specifically, conks were present at five unique locations around the base of the tree, suggesting an advanced fungal infection. The tree was scanned again and the area of decay depicted in 2023 (~25%) is almost identical to what was estimated in 2018. Tomography scans were captured at the same height on the lower trunk in 2018 and 2023. The diameter of the trunk at this height increased from 119.0 cm (46.9 in.) to 121.3 cm (47.7 in.) over five years. Therefore, while the decay is slowly continuing to increase in area, it does not appear to be outpacing diameter growth by the tree. As long as the tree continues to grow at a rate consistent with the growth of Niveoporofomes, the damage will appear unchanged in the tomograms. The tomograms, however, cannot account for decay in the roots, which may be increasing in severity at a faster rate. However, at present there is no corresponding dieback in the canopy, which appears very healthy.

Root and lower trunk rot of a mature black oak (Quercus velutina) on the UMass campus caused by Niveoporofomes spraguei. Luley describes Niveoporofomes as “common; probably more common than is realized because it is not well known by field arborists” (p. 72; Wood Decay Fungi Common to Urban Living Trees in the Northeast and Central United States, 2nd edition). This tree was evaluated for internal decay using sonic and electrical resistance tomography in Sept of 2018, although at the time the pathogen was unknown, as no conks or mushrooms were present. Recently, numerous N. spraguei conks were found growing from the lower trunk and root flare, close to the soil line. Specifically, conks were present at five unique locations around the base of the tree, suggesting an advanced fungal infection. The tree was scanned again and the area of decay depicted in 2023 (~25%) is almost identical to what was estimated in 2018. Tomography scans were captured at the same height on the lower trunk in 2018 and 2023. The diameter of the trunk at this height increased from 119.0 cm (46.9 in.) to 121.3 cm (47.7 in.) over five years. Therefore, while the decay is slowly continuing to increase in area, it does not appear to be outpacing diameter growth by the tree. As long as the tree continues to grow at a rate consistent with the growth of Niveoporofomes, the damage will appear unchanged in the tomograms. The tomograms, however, cannot account for decay in the roots, which may be increasing in severity at a faster rate. However, at present there is no corresponding dieback in the canopy, which appears very healthy.

Delayed symptom onset of freeze injury in flowering cherries (Prunus sp.). Numerous samples from a range of trees of various ages across the landscape. These trees have exhibited yellowing and premature leaf drop along with branch dieback. Symptoms typically developed during the heat of midsummer from late June onward. For some trees, the early February arctic freeze damaged the vascular tissue throughout the canopy, but these tissues were not killed outright. These affected branches were able to flush new growth this spring and appeared relatively healthy despite the injury. However, during the heat of summer, when transpirational demands increased, symptoms of dieback began to manifest. By cutting cross-sectional discs from the branches, the injured sapwood can be readily observed. It appears pinkish-brown throughout the cross-section, whereas healthy vascular tissue will appear mostly tan to pale green in color. In some cases, this discoloration is too nuanced to observe in the field but can be readily observed under magnification. Opportunistic cankering pathogens are colonizing small twigs and over time, will colonize larger diameter material.

Report by Nick Brazee, Plant Pathologist, UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab, UMass Amherst

Insects and Other Arthropods

Current Nuisance Problems of Note:

- Deer Tick/Blacklegged Tick: Ixodes scapularis adults are active all winter and spring, as they typically are from October through May, and “quest” or search for hosts at any point when daytime temperatures are above freezing. Engorged females survive the winter and lay 1,500+ eggs in the forest leaf litter beginning around Memorial Day (late May). For images of all deer tick life stages, along with an outline of the diseases they carry, visit: https://www.capecod.gov/departments/cooperative-extension/programs/ticks-bugs/ or https://web.uri.edu/tickencounter/species/blacklegged-tick/.

Anyone working in the yard and garden should be aware that there is the potential to encounter deer ticks. The deer tick or blacklegged tick can transmit Lyme disease, human babesiosis, human anaplasmosis, and other diseases. Preventative activities, such as daily tick checks, wearing appropriate clothing, and permethrin treatments for clothing (according to label instructions) can aid in reducing the risk that a tick will become attached to your body. If a tick cannot attach and feed, it will not transmit disease. For more information about personal protective measures, visit: https://www.capecod.gov/departments/cooperative-extension/programs/ticks-bugs/.

The Center for Agriculture, Food, and the Environment provides a list of potential tick identification and testing resources.

*In the news: UMass Amherst has now been designated as the location for the New England Center of Excellence in Vector-Borne Diseases (NEWVEC). This CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) funded center will work to reduce the risk of vector-borne diseases spread by ticks, mosquitoes, and other blood-sucking insects or insect relatives in New England. For more information and to contact NEWVEC, visit: https://www.newvec.org/. To contact the center for more information about their Spring 2023 Project ITCH (“Is Tick Control Helping”), visit: https://www.newvec.org/itch .

- Mosquitoes: According to the Massachusetts Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Science and the Department of Public Health, there are at least 51 different species of mosquito found in Massachusetts. Mosquitoes belong to the Order Diptera (true flies) and the Family Culicidae (mosquitoes). As such, they undergo complete metamorphosis, and possess four major life stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Adult mosquitoes are the only stage that flies and many female mosquitoes only live for 2 weeks (although the life cycle and timing will depend upon the species). Only female mosquitoes bite to take a blood meal, and this is so they can make eggs. Mosquitoes need water to lay their eggs in, so they are often found in wet or damp locations and around plants. Different species prefer different habitats. It is possible to be bitten by a mosquito at any time of the day, and again timing depends upon the species. Many are particularly active from just before dusk, through the night, and until dawn. Mosquito bites are not only itchy and annoying, but they can be associated with greater health risks. Certain mosquitoes vector pathogens that cause diseases such as West Nile virus (WNV) and eastern equine encephalitis (EEE).

Click here for more information about mosquitoes in Massachusetts.

EEE and WNV testing and tracking for this season began on June 12, 2023. The Massachusetts Department of Public Health tracks animal cases, human cases, and mosquito positive samples from traps from June through October in Massachusetts. The first West Nile Virus positive mosquito sample was collected on July 6, 2023, in the town of Brookline in Norfolk County, MA. Click here for more information. As of August 23, 2023, 74 positive WNV mosquito samples have been collected in the state. See the preceeding link for specific locations.

There are ways to protect yourself against mosquitoes, including wearing long-sleeved shirts and long pants, keeping mosquitoes outside by using tight-fitting window and door screens, and using insect repellents as directed. Products containing the active ingredients DEET, permethrin, IR3535, picaridin, and oil of lemon eucalyptus provide protection against mosquitoes. Be aware that not all of these can be safely used on young children. Read and follow all label instructions for safety and proper use.

Click here for more information about mosquito repellents.

- Wasps/Hornets: Many wasps are predators of other arthropods, including pest insects such as certain caterpillars that feed on trees and shrubs. Adult wasps hunt prey and bring it back to their nest where young are being reared, as food for the immature wasps. A common such example are the paper wasps (Polistes spp.) who rear their young on chewed up insects. They may be seen searching plants for caterpillars and other soft-bodied larvae to feed their young. Paper wasps can sting, and will defend their nests, which are open-celled paper nests that are not covered with a papery “envelope”. These open-celled nests may be seen hanging from eaves or other outdoor building structures. Aerial yellow jackets and hornets create large aerial nests that are covered with a papery shell or “envelope”. Common yellow jacket species include those in the genus Vespula. Dolichovespula maculata is commonly known as the baldfaced hornet, although it is not a true hornet. The European hornet (Vespa crabro) is three times the size of a yellow jacket and may be confused for the northern* giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia). The European hornet is known to Massachusetts, but the northern giant hornet is not. European hornets have black, tear-drop shaped markings on their abdomens, but northern giant hornets do not. If you are concerned that you have found or photographed a northern giant hornet, please report it here: https://massnrc.org/pests/report.aspx. Recent articles in the news have homeowners concerned about a new invasive species of hornet that is closely related to the northern giant hornet. The yellow-legged hornet (Vespa velutina) has been detected in Georgia as of August 2023. The yellow-legged hornet is native to Southeast Asia and smaller than the northern giant hornet. There is concern that the yellow-legged hornet, if allowed to establish in the USA, could pose a threat to honeybee health. More information can be found here: https://agr.georgia.gov/yellow-legged-hornet . If you suspect you’ve seen the yellow-legged hornet in Massachusetts, take a photo and submit a report here: https://massnrc.org/pests/report.aspx .

Paper wasps and aerial yellowjackets overwinter as fertilized females (queens) and a single female produces a new nest annually in the late spring. Queens start new nests, lay eggs, and rear new wasps to assist in colony/nest development.Nests are abandoned at the end of the season. Some people are allergic to stinging insects, so care should be taken around wasp/hornet nests. Unlike the European honeybee (Apis mellifera), wasps and hornets do not have barbed stingers, and therefore can sting repeatedly when defending their nests. It is best to avoid them, and if that cannot be done and assistance is needed to remove them, consult a professional.

*Read more about the common name change for Vespa mandarinia.

Woody ornamental insect and non-insect arthropod pests to consider, a selected few:

Highlighted Invasive Insects & Other Organisms Update:

Box Tree Moth: staff with the Mass. Dept. of Agricultural Resources (MDAR) and the USDA have recently confirmed several instances of boxwood shrubs on Cape Cod that were infested with the invasive pest known as box tree moth (Cydalima perspectalis). The finds have all been in established plantings (2 years old or more). It is unclear how the moths were introduced to the area or how widespread this pest is; USDA is currently working to delimit the infestation.

Box Tree Moth: staff with the Mass. Dept. of Agricultural Resources (MDAR) and the USDA have recently confirmed several instances of boxwood shrubs on Cape Cod that were infested with the invasive pest known as box tree moth (Cydalima perspectalis). The finds have all been in established plantings (2 years old or more). It is unclear how the moths were introduced to the area or how widespread this pest is; USDA is currently working to delimit the infestation.

The main host of box tree moth is boxwoods (Buxus spp.), though in their native range, the moths will also attack burning bush (Euonymus alatus) and a few other uncommon species, if boxwood is not available. The late-stage caterpillars cause significant defoliation and should be detectable now: check boxwoods for greenish brown caterpillars, 1 to 1.5 inches long, with black stripes running from head to tip, black heads, and long hairs scattered along the body. The caterpillars form webbing in the boxwoods to protect themselves, and in a heavy infestation this webbing fills up with visible clumps of frass pellets (waste material).

Box tree moths can cause complete defoliation of boxwoods, eventually killing entire shrubs. We encourage you to review the following fact sheet from the USDA to learn more about this pest, including how to recognize the adult moths, caterpillars, and eggs: ![]() Box Tree Moth Pest Alert

Box Tree Moth Pest Alert

If you grow, sell, or install boxwoods, please inspect them for any signs of this pest, and report any finds to https://massnrc.org/pests/report.aspx

- Elm Zigzag Sawfly: (Aproceros leucopoda) is a non-native insect that originated in eastern Asia (Japan and certain regions of China). It is now invasive in Europe (2003) and North America. The elm zigzag sawfly has been found in Virginia (2021), Maryland, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, New York, and Vermont. Be on the lookout for this invasive insect in Massachusetts!

As the common name suggests, the caterpillars of the elm zigzag sawfly feed on elm (Ulmus spp.). They may commonly feed on slippery elm (Ulmus rubra), winged elm (Ulmus alata), American elm (Ulmus americana), Siberian elm (Ulmus pumila), English elm (Ulmus minor 'Atinia'), lacebark elm (Ulmus parvifolia), and hybrid elms (Ulmus spp.). Hybrids found to be impacted in Virginia include: Ulmus ‘Cathedral’ Japanese x Siberian hybrid. Elms in both natural/forested areas as well as managed landscapes are fed upon by this insect.

Elm zigzag sawfly caterpillars are pale green with a black stripe on their heads and dark T-shaped markings on their legs. The larvae are small and can easily blend into the leaf; it may require close inspection to find. While they resemble the caterpillars of butterflies and moths, they are not. Sawflies are more closely related to the ants, bees, and wasps and their adults resemble a wasp with a broad waist. Adults are 6-7 mm long, shiny and black, with pale yellow legs and darkly colored wings. The adult sawflies do not sting humans. Once the caterpillar is fully mature (10-11 mm long) and ready to pupate, they spin a silken, net-like case around themselves. Pupae may change in color as they mature, from pale green to dark. Pupal cases are often found on host plant leaves, on the ground below, or on nearby objects. Thus far, no adult male zigzag sawflies have been found. The entire population is female and parthenogenetic - able to lay viable eggs without fertilization from a male. Two generations per year are known to occur in North Carolina and Virginia, however in Europe, 4-6 generations per year are possible.

Elm zigzag sawfly overwinters in the pupal life stage and adult females emerge as temperatures warm in the spring. As host plant foliage becomes available, females lay unfertilized eggs in tiny notches on the edges of leaves. Each female lives for approximately 1-6 days and lays up to 60 eggs (a range of 7-49 eggs per female has been reported). Eggs are tiny, and approximately 0.8-1.0 mm long when laid. Eggs are blue-green in color when first laid, but turn black just prior to hatching. Egg hatch can occur in approximately 4-8 days. Caterpillars feed for 15-18 days prior to pupation and pass through 6 instars. Caterpillars possess 3 pairs of hardened thoracic legs and 6 pairs of fleshy abdominal prolegs. The dark, T-shaped markings occur on the second and third pair of the hardened thoracic legs. Pupae in the summer months (if there are multiple generations per year) are in loosely woven nets, often attached to leaves. If leaves are not available, they may be attached to other nearby objects, including fence posts. Pupae destined to overwinter are often formed in the leaf litter or soil nearby the host plant, and are denser with solid walls. Adults that emerge from non-overwintering pupae can do so in approximately 10 days. In Europe, it is estimated that a full generation of these sawflies can occur in less than 1 month.

Females cause a tiny amount of damage to the edges of host plant leaves as they lay their eggs. Tiny scars are formed as a result of female egg laying. Eggs hatch and young sawfly caterpillars begin their characteristic zig-zag patterned feeding. These zig-zag shaped notches in the leaf can extend 5-10 mm into the leaf from the edge. Multiple caterpillars can feed on a single leaf. Entire leaves can be completely defoliated, leaving only veins behind. Heavily infested trees can suffer partial or complete defoliation. It is currently thought that elms can recover from periodic defoliation by this pest, however individual elm trees may be weakened and predisposed to other pests and stressors by elm zigzag sawfly feeding. If several years of complete defoliation occur in a row, tree mortality could possibly occur; however, this has not yet been observed in the US. Death of individual branches on susceptible hosts has been observed. The impact of this new invasive insect in the United States is not currently fully understood. In Europe, it is common that the elm zigzag sawfly outbreaks regularly and defoliates urban trees and large tracts of natural forest, however mortality of entire trees has not been reported there. Some trees are known to create new foliage following defoliation in a single season.

If you suspect you have seen damage caused by the elm zigzag sawfly in Massachusetts, please report it immediately to the MA Department of Agricultural Resources at: https://massnrc.org/pests/report.aspx .

- Southern Pine Beetle: Dendroctonus frontalis has been collected in traps in Massachusetts and other parts of New England in recent years. Historically, the southern pine beetle has been native to the southeastern United States, however its range is moving northward due to warming winters and climate change. The Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) Forest Health Program, has announced that they have detected the first pocket of southern pine beetle killed trees (pitch pine, Pinus rigida) in Massachusetts on Nantucket. This is the first observation of this species killing trees in the state. An active infestation of southern pine beetle was found killing trees in July and MA DCR is working with the property owner to determine next steps and potential management options at the site. If you believe you have detected southern pine beetles in trees in Massachusetts, please contact Nicole Keleher, MA DCR Forest Health Director, at: nicole.keleher@mass.gov. More information about southern pine beetle is also available from MA DCR at https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/b60f63199fa14805a8b9f7c82447a25b .

The southern pine beetle (SPB) undergoes complete metamorphosis (is holometabolous) with four life stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Adults are dark red/brown to black in color and 1/16 – 1/8” in length. Eggs are white and larvae are crescent-shaped with a dark red/brown head and a white body. Four larval instars are present, with pupa being bright white. The adult is light brown in color prior to drying and hardening and becoming darker in color. Female beetles select suitable host trees and release chemical pheromones to attract male mates. She will penetrate the bark and begin creating a gallery where she is joined by the male and mates. Early attacks to the tree may be “pitched out” by the resin defenses of the tree. The pheromones produced by the females and the volatile chemicals expressed by the stressed host plant attract additional males and females. If tree defenses can be overcome, females will colonize beneath the bark, creating S-shaped galleries. The inoculation of the tree with a blue stain fungus as well as other fungi occurs with colonization of southern pine beetle, however, it is the act of "mass attack" by the insects themselves which leads to tree mortality. Entomocorticium spp. symbiotic fungi are associated with southern pine beetles and the immature larvae feed on this fungus. Females may lay up to 160 eggs in their lifetime and development can take as little as 26 days in warmer climates. In the South, 3-9 generations of SPB have been observed to occur per year. In NY, 3-4 generations have been observed on Long Island. Current Massachusetts temperatures should keep the number of generations per year to the lower end of this range.

Southern pine beetle can be detected most easily by the presence of popcorn-sized pitch tubes on the outer bark of trunks and branches. Pitch tubes can range in color from white to red. They can occur from ground level to high in the canopy of the tree. Exit holes (about 1/16” in diameter) can be observed in the bark from emerging adults. S-shaped galleries can also be observed by peeling back any bark that may be falling off the tree. Brown-orange frass (excrement) that looks like wood shavings is found packed within the galleries. By the time foliage fades from green to yellow to brown, the infestation may be advanced. The presence of certain checkered or clerid beetles can also indicate high populations of southern pine beetle, as these checkered beetles prey upon SPB. Southern pine beetle prefers trees damaged by lightning strikes or fire. In the southeastern part of the insect's range, southern pine beetle is not known to preferentially attack drought stressed or chronically stressed trees. Trees under 15 years of age or 2 inches in diameter may be seldom attacked.

Spotted Lanternfly: (Lycorma delicatula, SLF) is a non-native, invasive insect that feeds on over 103 species of plants, including many trees and shrubs that are important in our landscapes. It overwinters as an egg mass, which the adult female insect lays on just about any flat surface. Pictures of egg masses can be seen here.

Spotted Lanternfly: (Lycorma delicatula, SLF) is a non-native, invasive insect that feeds on over 103 species of plants, including many trees and shrubs that are important in our landscapes. It overwinters as an egg mass, which the adult female insect lays on just about any flat surface. Pictures of egg masses can be seen here.

Eggs have hatched and spotted lanternfly will pass through four nymphal instars before maturing into the adult life stage. Adults are typically present by late July and the beginning of August.

Currently, the only established populations of spotted lanternfly in Massachusetts are in Fitchburg, Shrewsbury, Worcester, and Springfield MA. Therefore, there is no reason to be preemptively treating for this insect in other areas of Massachusetts. If you suspect you have found spotted lanternfly in additional locations, please report it immediately to MDAR here. If you are living and working in the Fitchburg, Shrewsbury, Worcester, and Springfield, MA areas, please be vigilant and continue to report anything suspicious.

For More Information:

From UMass Extension:

*New*: Spotted Lanternfly Management Guide for Professionals

*Note that management may only be necessary in areas where this insect has become established in Massachusetts, and if high value host plants are at risk. Preemptive management of the spotted lanternfly is not recommended.

Check out the InsectXaminer Episode about spotted lanternfly adults and egg masses!

From the MA Department of Agricultural Resources (MDAR):

Spotted Lanternfly Fact Sheet and Map of Locations in MA

Spotted Lanternfly Management Guide for Homeowners in Infested Areas

*New*: Spotted Lanternfly Look-alikes in MA

*New*: Spotted Lanternfly Egg Mass Look-alikes

- Asian Longhorned Beetle: (Anoplophora glabripennis, ALB) Look for signs of an ALB infestation which include perfectly round exit holes (about the size of a dime), shallow oval or round scars in the bark where a female has chewed an egg site, or sawdust-like frass (excrement) on the ground nearby host trees or caught in between branches. Be advised that other, native insects may create perfectly round exit holes or sawdust-like frass, which can be confused with signs of ALB activity.

Adult Asian longhorned beetles typically begin to emerge from trees by July 1st in Massachusetts. It is important to take photographs of and report any suspicious longhorned beetles to the Asian Longhorned Beetle Eradication Program phone numbers listed below.

The regulated area for Asian longhorned beetle is 110 square miles encompassing Worcester, Shrewsbury, Boylston, West Boylston, and parts of Holden and Auburn. If you believe you have seen damage caused by this insect, such as exit holes or egg sites, on susceptible host trees like maple, please call the Asian Lonbghorned Beetle Eradication Program office in Worcester, MA at 508-852-8090 or toll free at 1-866-702-9938.

Report an Asian longhorned beetle find online or compare it to common insect look-alikes here.

Emerald Ash Borer: (Agrilus planipennis, EAB) has been detected throughout much of Massachusetts and it was recently detected for the first time in Barnstable County. A map of these locations across the state is provided by the MA Department of Conservation and Recreation at https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/b60f63199fa14805a8b9f7c82447a25b.

Emerald Ash Borer: (Agrilus planipennis, EAB) has been detected throughout much of Massachusetts and it was recently detected for the first time in Barnstable County. A map of these locations across the state is provided by the MA Department of Conservation and Recreation at https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/b60f63199fa14805a8b9f7c82447a25b.

This wood-boring beetle readily attacks ash (Fraxinus spp.) including white, green, and black ash and has also been found developing in white fringe tree (Chionanthus virginicus) and has been reported in cultivated olive (Olea europaea). Signs of an EAB infested tree may include D-shaped exit holes in the bark (from adult emergence), “blonding” or lighter coloration of the ash bark from woodpecker feeding (chipping away of the bark as they search for larvae beneath), and serpentine galleries visible through splits in the bark, from larval feeding beneath. It is interesting to note that woodpeckers are capable of eating 30-95% of the emerald ash borer larvae found in a single tree (Murphy et al. 2018). Unfortunately, despite high predation rates, EAB populations continue to grow. However, there is hope that biological control efforts will eventually catch up with the emerald ash borer population and preserve some of our native ash tree species for the future.

- Jumping Worms: Amynthas spp. earthworms, collectively referred to as “jumping or crazy or snake” worms, overwinter as eggs in tiny, mustard-seed sized cocoons found in the soil or other substrate (ex. compost). Immature jumping worms hatch from their eggs by approximately mid-to-late May. It may be impossible to see them at first, and it may be more likely that jumping worms are noticed when the first adults begin to appear at the end of May and in June. It is easy to misidentify jumping worms (ex. mistake European earthworms for jumping worms) if only juveniles are found. In August and September, most jumping worms have matured into the adult life stage and identification of infestations is more likely to occur at that time of year.

For More Information, see these UMass Extension Fact Sheets:

Earthworms in Massachusetts – History, Concerns, and Benefits

Jumping/Crazy/Snake Worms – Amynthas spp.

A Summary of the Information Shared at UMass Extension’s Jumping Worm Conference in January 2022

Invasive Jumping Worm Frequently Asked Questions (Over 70 Questions and their Answers)

Tree & Shrub Insect Pests (Native and Invasive):

- Andromeda Lace Bug: Stephanitis takeyai is most commonly encountered on Japanese Andromeda. Eggs are tiny and inserted into the midveins on the lower surface of the leaf and covered with a coating that hardens into a protective covering. 5 nymphal stages are reported. Nymphs are different in appearance from the adults, often covered with spiky protrusions. 3-4 generations per year have been observed in New England, with most activity seen between late-May into September (starting at approximately 120 GDD’s, Base 50°F). Both nymphs and adults can be seen feeding on leaf undersides. Adults have delicate, lace-like wings and what appears to be an "inflated hood" that covers their head. Adults are approximately 1/8 of an inch long. Arrived in the US in Connecticut in 1945 from Japan (Johnson and Lyon, 1991).

Can cause severe injury to Japanese andromeda, especially those in full sun. Mountain Andromeda (Pieris floribunda) is highly resistant to this pest. Like other lace bugs, this insect uses piercing-sucking mouthparts to drain plant fluids from the undersides of the leaves. Damage may be first noticed on the upper leaf surface, causing stippling and chlorosis (yellow or off-white coloration). Lace bug damage is distinguished from that of other insects upon inspecting the lower leaf surface for black, shiny spots, "shed" skins from the insects, and adult and nymphal lace bugs themselves.

A first sign of potential lace bug infestation is stippling or yellow/white colored spots or chlorosis on host plant leaf surfaces. Lace bugs excrete a shiny, black, tar-like excrement that can often be found on the undersides of infested host plant leaves. Flip leaves over to inspect for this when lace bug damage is suspected.

Mountain Andromeda (Pieris floribunda) is considered to be highly resistant to this insect and can be used as an alternative for such plantings, along with other lace bug-resistant cultivars. Consider replacing Japanese Andromeda with mountain andromeda as a way to manage for this pest. Natural enemies are usually predators, and sometimes not present in large enough numbers in landscapes to reduce lace bug populations. Structurally and (plant) species complex landscapes have been shown to reduce azalea lace bug (Stephanitis pyrioides) populations through the increase of natural enemies.

- Asiatic Garden Beetle: Maladera castanea adults are active and are typically most abundant in July and August. These rusty-red colored beetles are bullet-shaped and active at night. They are often attracted to porch lights. This beetle feeds on a number of ornamental plants, defoliating leaves by giving the edges a ragged appearance and also feeding on blossoms. Butterfly bush, rose, dahlia, aster, and chrysanthemum can be favored hosts.

Bagworm: Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis is a native species of moth whose larvae construct bag-like coverings over themselves with host plant leaves and twigs. This insect overwinters in the egg stage, within the bags of deceased females from last season. Eggs may hatch and young larvae are observed feeding around mid-June, or roughly between 600-900 GDD’s. Newly hatched and feeding bagworm caterpillars are small and less likely to be noticed. By late July and August, these caterpillars will be large and their feeding noticeable on individual trees and shrubs. Bagworm caterpillars were observed in abundance feeding on columnar hornbeam planted approximately 5 years ago in Amherst, MA on 7/19/2023 and reported by Alan Snow, Tree Warden, Town of Amherst. The tree was almost completely defoliated, with brown leaves looking as if they were scorched by fire. Approximately ½ inch long caterpillars littered the ground beneath the tree and could be seen climbing up the trunk or dangling from branches on silken threads. Continue to monitor susceptible host plants for bagworm caterpillars into August.

Bagworm: Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis is a native species of moth whose larvae construct bag-like coverings over themselves with host plant leaves and twigs. This insect overwinters in the egg stage, within the bags of deceased females from last season. Eggs may hatch and young larvae are observed feeding around mid-June, or roughly between 600-900 GDD’s. Newly hatched and feeding bagworm caterpillars are small and less likely to be noticed. By late July and August, these caterpillars will be large and their feeding noticeable on individual trees and shrubs. Bagworm caterpillars were observed in abundance feeding on columnar hornbeam planted approximately 5 years ago in Amherst, MA on 7/19/2023 and reported by Alan Snow, Tree Warden, Town of Amherst. The tree was almost completely defoliated, with brown leaves looking as if they were scorched by fire. Approximately ½ inch long caterpillars littered the ground beneath the tree and could be seen climbing up the trunk or dangling from branches on silken threads. Continue to monitor susceptible host plants for bagworm caterpillars into August.

- Fall Home-Invading Insects: Various insects, such as ladybugs, boxelder bugs, seedbugs, and stink bugs will begin to seek overwintering shelters in warm places, such as homes, throughout the next couple of months. While such invaders do not cause any measurable structural damage, they can become a nuisance especially when they are present in large numbers. While the invasion has not yet begun, if you are not willing to share your home with such insects, now should be the time to repair torn window screens, repair gaps around windows and doors, and sure up any other gaps through which they might enter the home.

- Fall Webworm: Hyphantria cunea is native to North America and Mexico. It is now considered a world-wide pest, as it has spread throughout much of Europe and Asia. (For example, it was introduced accidentally into Hungary from North America in the 1940’s.) Hosts include nearly all shade, fruit, and ornamental trees except conifers. In the USA, at least 88 species of trees are hosts for these insects, while in Europe at least 230 species are impacted. In the past history of this pest, it was once thought that the fall webworm was a two-species complex. It is now thought that H. cunea has two color morphs – one black headed and one red headed. These two color forms differ not only in the coloration of the caterpillars and the adults, but also in their behaviors. Caterpillars may go through at least 11 molts, each stage occurring within a silken web they produce over the host. When alarmed, all caterpillars in the group will move in unison in jerking motions that may be a mechanism for self-defense. Depending upon the location and climate, 1-4 generations of fall webworm can occur per year. Fall webworm adult moths lay eggs on the underside of the leaves of host plants in the spring. These eggs hatch in late June or early July depending on climate. Young larvae feed together in groups on the undersides of leaves, first skeletonizing the leaf and then enveloping other leaves and eventually entire branches within their webs. Webs are typically found on the terminal ends of branches. All caterpillar activity occurs within this tent, which becomes filled with leaf fragments, cast skins, and frass. Fully grown larvae then wander from the webs and pupate in protected areas such as the leaf litter where they will remain for the winter. Adult fall webworm moths emerge the following spring/early summer to start the cycle over again. 50+ species of parasites and 36+ species of predators are known to attack fall webworm in North America. Fall webworms typically do not cause extensive damage to their hosts. Nests may be an aesthetic issue for some. If in reach, small fall webworm webs may be pruned out of trees and shrubs and destroyed. Do not set fire to H. cunea webs when they are still attached to the host plant.

- Hickory Tussock Moth: Lophocampa caryae is native to southern Canada and the northeastern United States. There is one generation per year. Overwintering occurs as a pupa inside a fuzzy, oval shaped cocoon. Adult moths emerge approximately in May and their presence can continue into July. Females will lay clusters of 100+ eggs together on the underside of leaves. Females of this species can fly, however they have been called weak fliers due to their large size. When first hatched from their eggs, the young caterpillars will feed gregariously in a group, eventually dispersing and heading out on their own to forage. Caterpillar maturity can take up to three months and color changes occur during this time. These caterpillars are essentially white with some black markings and a black head capsule. They are very hairy, and should not be handled with bare hands as many can have skin irritation or rashes (dermatitis) as a result of interacting with hickory tussock moth hairs. By late September, the caterpillars will create their oval, fuzzy cocoons hidden in the leaf litter where they will again overwinter. Hosts whose leaves are fed upon by these caterpillars include but are not limited to hickory, walnut, butternut, linden, apple, basswood, birch, elm, black locust, and aspen. Maple and oak have also been reportedly fed upon by this insect. Several wasp species are parasitoids of hickory tussock moth caterpillars.

- Magnolia Scale: Neolecanium cornuparvum is distributed throughout the eastern United States. Host plants include: Magnolia stellata (star Magnolia), M. acuminata (cucumber magnolia), M. lilliflora ‘Nigra’ (lily magnolia; formerly M. quinquepeta), and M. soulangeana (Chinese magnolia). Other species may be hosts for this scale but attacked to a lesser degree. M. grandiflora (southern magnolia) may be such an example.

Mature individuals settle on a location on branches and twigs, then insert piercing-sucking mouthparts to feed. The insects feed on plant fluids and excrete large amounts of a sugary substance known as honeydew. Sooty mold, often black in color, will then grow on the honeydew that has coated branches and leaves. Repeated, heavy infestations can result in branch dieback and at times, death of the plant. Honeydew may also be very attractive to ants, wasps, and hornets. The magnolia scale overwinters as a young nymph (immature stage) which is elliptical in shape, mostly a dark-slate gray, except for a median ridge that is red/brown in color. These overwintering nymphs may be found on the undersides of 1st and 2nd year old twigs. The first molt (shedding of the exoskeleton to allow growth) can occur by late April or May in parts of this insect’s range and the second molt will occur in early June. At that time, the immature scales have turned a deep purple color. Stems of the host plant may appear purple in color and thickened – but this is a coating of nymphal magnolia scales, not the stem itself. Eventually, these immature scales secrete a white layer of wax over their bodies, looking as if they have been rolled in powdered sugar. By August, the adult female scale is fully developed, elliptical and convex in shape, and ranging from a pinkish-orange to a dark brown color. Adult females may also be covered in a white, waxy coating. By that time, the females produce nymphs (living young; eggs are not “laid”) that wander the host before settling on the newest twigs to overwinter. In the Northeastern United States, this scale insect has a single generation per year.

- Mimosa Webworm: Homadaula anisocentra was first detected in the United States in 1940 in Washington, D.C. on its common namesake host plant. Originally from China, the mimosa webworm is primarily a pest of honeylocust (Gleditsia triacanthos; including thornless cultivars). This insect is found throughout the eastern and midwestern states and California. In the warmer parts of its range in the United States, it has historically heavily attacked mimosa where it grows. Adults are moths that are silvery gray in color with wings interrupted by black dots. Moths are approximately 13 mm in size (wingspan). Fully grown larvae reach up to 16 mm long and are variable in color from gray to brown with five longitudinal white stripes. Once mature, the caterpillars move to the bark scales of their host plants and find sheltered places to pupate. They may also be found in the leaf litter beneath host plants, pupating in a cocoon. Pupae are yellowish brown, 6 mm long, and encased in a white cocoon. Adult moths may emerge in early-mid June and lay gray eggs on the leaves of their hosts that turn a rose color just prior to hatch. Eggs hatch and feeding caterpillars web the foliage together, feeding within the web for protection. Larvae may be found feeding together in groups, in which case larger and aesthetically displeasing webs may be created. If disturbed, the larvae may move quickly and can drop from the web on a line of silk. A second generation of moths may occur, with pupation happening and adults emerging by August in warmer locations. In New York and New England, it is likely that this second generation emerges in September and any offspring may be killed with the winter. In the warmest parts of this insect's introduced range in the United States, three generations may be possible per year.

The larvae (caterpillars) of this insect tie the foliage of their hosts together with silken strands and skeletonize the leaves. Injury to host plant leaves may be noticeable by early July in Massachusetts. Foliage can appear bronzed in color from the feeding. Webbing usually begins at the tops of trees. An entire tree may become covered in the webs created by these caterpillars. So much webbing can often make it difficult to assess the extent of the defoliation or damage caused on an individual host.

Certain cultivars of honeylocust may vary in their susceptibility to this insect. Gleditsia triacanthos 'Sunburst' was highly susceptible to attack in Indiana. Cultivars such as 'Moraine', 'Shademaster', and 'Imperial' may be less susceptible - however, they are still able to be fed upon by this insect, so annual monitoring may be necessary.

Viburnum Leaf Beetle: Pyrrhalta viburni is a beetle in the family Chrysomelidae that is native to Europe, but was found in Massachusetts in 2004. By 2008, viburnum leaf beetle was considered to be present throughout all of Massachusetts. Larvae are present and feeding on plants from approximately late April to early May until they pupate sometime in June. Much damage from viburnum leaf beetle feeding is currently apparent in areas of Massachusetts where this insect has become established. See photo courtesy of Tom Ingersoll from 6/5/2023. Adult beetles emerge from pupation by approximately mid-July and will also feed on host plant leaves, mate, and lay eggs at the ends of host plant twigs where they will overwinter. This beetle feeds exclusively on many different species of viburnum, which includes, but is not limited to, susceptible plants such as V. dentatum, V. nudum, V. opulus, V. propinquum, and V. rafinesquianum. Some viburnum have been observed to have varying levels of resistance to this insect, including but not limited to V. bodnantense, V. carlesii, V. davidii, V. plicatum, V. rhytidophyllum, V. setigerum, and V. sieboldii. More information about viburnum leaf beetle may be found at http://www.hort.cornell.edu/vlb/ and at https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/viburnum-leaf-beetle.

Viburnum Leaf Beetle: Pyrrhalta viburni is a beetle in the family Chrysomelidae that is native to Europe, but was found in Massachusetts in 2004. By 2008, viburnum leaf beetle was considered to be present throughout all of Massachusetts. Larvae are present and feeding on plants from approximately late April to early May until they pupate sometime in June. Much damage from viburnum leaf beetle feeding is currently apparent in areas of Massachusetts where this insect has become established. See photo courtesy of Tom Ingersoll from 6/5/2023. Adult beetles emerge from pupation by approximately mid-July and will also feed on host plant leaves, mate, and lay eggs at the ends of host plant twigs where they will overwinter. This beetle feeds exclusively on many different species of viburnum, which includes, but is not limited to, susceptible plants such as V. dentatum, V. nudum, V. opulus, V. propinquum, and V. rafinesquianum. Some viburnum have been observed to have varying levels of resistance to this insect, including but not limited to V. bodnantense, V. carlesii, V. davidii, V. plicatum, V. rhytidophyllum, V. setigerum, and V. sieboldii. More information about viburnum leaf beetle may be found at http://www.hort.cornell.edu/vlb/ and at https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/viburnum-leaf-beetle.

Concerned that you may have found an invasive insect or suspicious damage caused by one? Need to report a pest sighting? If so, please visit the Massachusetts Introduced Pests Outreach Project.

Reported by Tawny Simisky, Extension Entomologist, UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, & Urban Forestry Program

Landscape Weeds

For identification of weed species noted below, refer to UMass Extension's Weed Herbarium.

“Sterile” culivars of Japanese barberry. Received a message this week from Dr. Jennifer Forman Orth, Environmental Biologist with the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources (MDAR). The Cooperative Agricultural Pest Survey (CAPS) pest detection program supports the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) as it works to safeguard U.S. agricultural and environmental resources by ensuring that new introductions of harmful plant pests and diseases are detected as soon as possible. Early detection often reduces the chances these pests have to cause significant damage. Jennifer mentioned that during MDAR nursery inspections it was discovered that a few nurseries in the commonwealth were selling Japanese barberry. When questioned about why they were selling Japanese barberry, they responded that it was a “sterile cultivar” and as such it was assumed to be OK.

Jennifer generously shared the following information about Massachusetts invasive plants, the Massachusetts Prohibited Plant List, and the “sterile” cultivar issue: This is just a reminder that the Massachusetts Prohibited Plant List prohibits the sale, trade, import, or propagation of over 100 invasive plant species in the state. That includes all cultivars of listed plants, even ones that are labeled as sterile or otherwise claim to not be invasive. The Massachusetts Invasive Plant Advisory Group (MIPAG) is currently exploring whether at some point sterile cultivars might be able to be reintroduced to the commonwealth, but until such time as a protocol is set up, the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources will continue to prohibit any cultivars, varieties, or hybrids of listed plants.

Additional resources and information can be found by visiting:

From the frequently asked questions section on MDAR's prohibited plants web page:

Q: What about sterile hybrids or cultivars of invasive plant species labeled as "non-invasive"?

A. Until such time that MDAR nursery inspectors are able to clearly recognize that a hybrid, variety, or cultivar of a species on the Prohibited Plant List is truly non-invasive or sterile (does not produce viable seed), these plants will be included in the list. Also note that invasive plants often spread by more than one method and may have the ability to reproduce vegetatively in a way that negatively impacts the environment.

Japanese knotweed is in full flower; now it is the time to manage this invasive plant. Applications of glyphosate are the best choice for Japanese knotweed management. For areas near and around water, you will need to use a glyphosate formulation that is labeled for these areas. Since knotweed commonly grows in wet areas or near streams, rivers, or wetlands, the management of this invasive plant may invoke 310 CMR 10.00: the Massachusetts Wetlands Protection Act. 310 CMR 10.00 regulates all activities in the resource areas identified in the act. Before any management attempts are carried out, you should contact the Conservation Commission in the municipality to determine to what extent 310 CMR 10.00 might impact your project. For states other than Massachusetts, you should seek information about that state’s regulations for activities near water.

Common reed or phragmites, Phragmites australis, is in flower in New England, so now is the time for herbicide treatment. Glyphosate-based herbicide products are the best choice for the control of common reed. In areas near water, a formulation of glyphosate that is labeled for these areas should be used. Since common reed is most commonly associated with water and wet habits, 310 CMR 10.00 might be invoked. See comments in the Japanese knotweed section above for details about 310 CMR 10.00.

Reported by Randy Prostak, Weed Specialist, UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, & Urban Forestry Program

Additional Resources

Pesticide License Exams - The MA Dept. of Agricultural Resources (MDAR) is now holding exams online. For more information and how to register, go to: https://www.mass.gov/pesticide-examination-and-licensing.

To receive immediate notification when the next Landscape Message update is posted, join our e-mail list or follow us on Facebook.