Managing Insects in Your Garden

Frank Mangan and Heriberto Godoy-Hernandez

To read individual sections of this article, click on the section headings below to expand the content:

Welcome to this eighth article of Franco and Beto’s series on growing your own vegetables and herbs in Massachusetts. In this column, we focus on managing insect pests in gardens.

There are three basic categories of insects in gardens: Beneficial Insects, insect pests, and interlopers. We’ll briefly describe each.

Beneficial Insects

These, as the name implies, are insects we want to keep around! One important group of beneficial insects are those that assist in pollinating fruiting vegetables and herbs. There are two basic types of fruiting vegetables and herbs grown in gardens – dioecious and monecious.

- Dioecious flowering plants, also known as plants with “perfect flowers”, are flowering plants where each flower has both the male sexual organ (stamen) and the female sexual organ (stigma) on the same flower. Pollination with these plants takes place mostly with wind and rain/irrigation. Insects, including bees, can assist in this process, but are not necessary for pollination to occur. Examples of self-pollinating vegetables commonly grown in gardens are tomatoes, peppers, eggplants, green beans, and sweet peas.

- Monecious flowering plants have separate male and female flowers on the same plant. Insects, especially bees, play a critical role in pollinating these plants, moving pollen from male flowers to female flowers. Examples of monoecious vegetables are summer and winter squashes, cantaloupe, watermelon, and sweet corn.

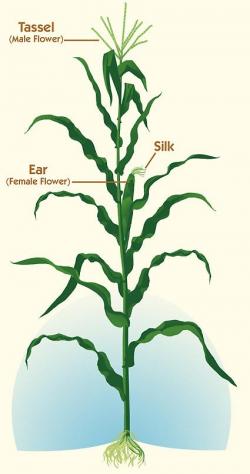

Even though sweet corn is monoecious, it does not need bees or other insects to assist in pollination. Sweet corn has both male and female flowers; however, pollination takes place mostly due to gravity and wind (Figure 1). The male flowers, where pollen is produced, make up the corn tassel, which emerges from the top of the plant. The female flowers form within the developing ear, and corn silks are the stigmas of those female flowers. Each silk correlates to 1 flower, inside the ear, and each flower will become a single kernel of corn. Pollen is shed from the tassels at the top of the plant, with the assistance from gravity and wind, and pollination takes place when pollen lands on a silk. Pollen must land on each individual strand of silk in order to create an ear of corn without any missing kernels. In order to achieve this, you have to plant several corn plants in a group so the pollen will pollinate each silk. It is recommended to plant, at a minimum, a block of four by four sweet corn plants to ensure 100% pollination.

Even though sweet corn is monoecious, it does not need bees or other insects to assist in pollination. Sweet corn has both male and female flowers; however, pollination takes place mostly due to gravity and wind (Figure 1). The male flowers, where pollen is produced, make up the corn tassel, which emerges from the top of the plant. The female flowers form within the developing ear, and corn silks are the stigmas of those female flowers. Each silk correlates to 1 flower, inside the ear, and each flower will become a single kernel of corn. Pollen is shed from the tassels at the top of the plant, with the assistance from gravity and wind, and pollination takes place when pollen lands on a silk. Pollen must land on each individual strand of silk in order to create an ear of corn without any missing kernels. In order to achieve this, you have to plant several corn plants in a group so the pollen will pollinate each silk. It is recommended to plant, at a minimum, a block of four by four sweet corn plants to ensure 100% pollination.

See Pollination of Vegetable Crops from the University of Florida Extension program for more information on pollinating relevant to vegetable crops, including diagrams of different flower types mentioned above.

There are many other beneficial insects in gardens, including those that feed on or parasitize insect pests, like ladybugs, praying mantis, spiders, beneficial wasps, hover flies, and others.

Insect Pests

These can cause damage or totally destroy vegetables and herbs. I will describe two examples of insect pests I have had in my garden so far this season and how I went through the process to consider managing them and how.

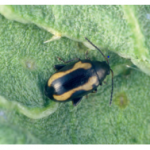

I found this insect (Figure 2) on a tomatillo plant (Physalis philadelphica, Physalis ixocarpa) in my garden on June 9. I have never seen this insect before and when I first saw it, I did not see any feeding damage on leaves, stems, or flowers, so I just ignored it, thinking it was a beneficial insect or an interloper. With time I began to see increasing damage on the tomatillo leaves (Figure 3), so I then began a process to identify this insect to determine if it was something I should consider managing.

Here is the process I used:

- Step one: Identification. The first step in addressing an agricultural pest is to identify it before deciding whether or not to control it. The first thing I did was to get a good picture of both the pest (Figure 2, above) and the damage it was causing on the tomatillos (Figure 3, above).

- Step two. Search sources where you can find pictures of pests that feed on the target plant. It is best to start with sources which focus on insect pests found in New England, and one place to start is the Northeast Vegetable and Strawberry Pest Identification Guide (Figure 4) published by the six New England Land Grant Universities, and available online for free. This guide has pictures of common weeds, insects, and diseases and disorders of major vegetables, herbs, and strawberries found in New England. This guide is organized into Weeds, Insects, Diseases & Disorders, and Strawberry Pests sections, with alphabetical lists of pests for each section followed by a picture of each pest. While the guide focuses on pests, it also includes some beneficial insects. There are four sections of this guide:

- Weeds of vegetables and Strawberries

- Vegetable Insects and Mites

- Vegetable Diseases & Disorders

- Strawberry Pests and Diseases (not relevant to these articles, but useful if you have strawberries)

Since we’re interested in insects, we can click on “Vegetable Insects and Mites” in the list above. The common names for insects and mites are listed in alphabetical order, followed by the scientific names. I reviewed all the pictures of insects listed, which does not take a lot of time if you have a good picture of the pest you’re looking for, but I did not see one that resembled the insect in question.

Since tomatillos are in the solanaceous family, I then reviewed insect pests listed for all the vegetables in the solanaceous family listed in the New England Vegetable and Management Guide (NEVMG): tomatoes, peppers, eggplants, and potatoes. I was familiar with all the insects listed for these crops and knew the pest in question was not in the NEVMG. If you are not familiar with the name of an insect pest listed for each of the members of the solanaceous family in the NEVMG, you can google them using both the common names and scientific names, both listed in the NEVMG. Selecting in google to list “images” will be the most useful. If you find a picture of the pest in question, you should then be able to find the common and scientific names online.

After exhausting the NEVMG, I did a Google search with the following descriptors of the pest: “beetle” “yellow” “three black stripes”, “long antenna”, “tomatillos”, and multiple combinations. I eventually came across a picture that matched my pest, and this brought me to the common name “three-lined potato beetle”, and scientific name Lema daturaphila. With this information I found many sites with information on this insect, including a fact sheet by an entomologist at the University of New Hampshire, Three Lined Potato Beetle, where it states this insect is…”uncommon on potato, rare on tomato, but very common on tomatillo…”. My two tomatillo plants are in the same bed as three other solanaceous plants: tomatoes, peppers, and eggplant, yet I have only found this insect on tomatillos, which supports the comment on this insects’ preference

Given the seriousness of the increased feeding damage on the tomatillo leaves, I decided to manage the three-lined potato beetle with my index finger and thumb (squishing them), which was easy to do and very effective!

The second insect pest I have dealt with so far in my garden this season has been flea beetles, a family of insects I am very familiar with; they are very common pests in Massachusetts on members of the brassica and solanaceous families – go to Food Gardening in Massachusetts 2020 Vol. 1:11 about brassica vegetables , and click on “insect problems” to see more information on flea beetles.

Since I am familiar with flea beetles, I did not have to go through the steps listed above to identify the three-lined potato beetle, but you can use the same process to identify the flea beetle find them as described above with the three lined potato beetle. (Note: flea beetles are small, and it is the damage on leaves that is distinctive.)

There are two species of flea beetles commonly found on brassicas in Massachusetts and the life cycle and damage caused by both are very similar. The crucifer flea beetle, which is uniformly black and shiny (Figure 5), and the striped flea beetle (Figure 6), named due to two yellow stripes on it back. Both are very small, 2 mm in length, which makes them difficult to see; however, the damage they cause is very easy to identify (See link above Figure 7).

One option to manage flea beetles is with the use of row cover or netting, which can exclude the pest from feeding on the brassica crops under the protective cover. I use row cover extensively in my garden early in the season, and in my research with certain crops, the use of which we shared in “Use of Row Covers”, in Food Gardening in Massachusetts 20202 Vol. 1:3 - click on “Use of Row Covers”.

Both flea beetle species can fly and crawl, which allows them to crawl under the edges of the row cover if they are not “sealed” by putting some soil on the edges of the row cover. In my garden, I don’t normally seal the edges of the row cover, since it is labor intensive to uncover and then cover a bed every time I take the row cover off to weed, harvest or check the plants. The damage flea beetles cause can lead to a reduction in yield, but normally won’t kill the plant, so I just accept it. Commercial farmers will be under more pressure to manage flea beetles because customers at grocery stores and markets may have higher standards than my wife and I have for our garden!

Interlopers

These are basically all insects that are neither beneficial nor pests and are just passing through the garden. You don’t want to manage an interloper, even if it doesn’t play a role in your garden, since it may play an important role in other ecosystems in the vicinity.