Water Management for Vegetables and Herbs in Your Garden

Frank Mangan and Heriberto Godoy-Hernandez

To read individual sections of this article, click on the section headings below to expand the content:

Welcome to this fifth article of Franco and Beto’s series on growing your own vegetables and herbs in Massachusetts.

<>Introduction

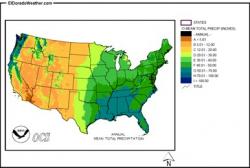

All plants need water to develop; the amount of water needed for optimum growth varies between plant species and environmental conditions. Rain is an important source of water in Massachusetts, where we receive an average of 50 inches of precipitation per year (Figure 1).

If these 50 inches of rain were distributed evenly over the course of a year, it would provide more than enough water for vegetable and herb production in Massachusetts. However, obviously that is not the case. During the growing season, we can experience prolonged dry periods during which we must apply water (irrigate) to ensure that our vegetables and herbs produce desired yields and quality. At other times, we receive excess rain during the growing season, which can cause the leaching of nutrients from the soil and can cause foliar and root diseases. Disease-causing fungal spores and bacterial cells are often not released or infect plant tissue until they have been wet for a certain period of time . The longer vegetable and herb tissues are wet, the more likely they will become diseased.

There are many factors that dictate the amount of water a vegetable or herb species needs to for optimum growth. As an example, during the heat of the summer in Massachusetts, a mature crop of tomatoes can require 2.5 quarts of water per day per plant, while winter greens may not need to be irrigated all winter long and may in fact suffer from foliar diseases or the effects of nutrient leaching if water is applied. Determining the optimal amount and timing of irrigation can be complicated since it depends on multiple factors, including the specific vegetable and herb species, its stage of growth, soil texture, sunlight, temperature, and humidity – see the New England Vegetable Management Guide for information on irrigation.

Determining the Amount of Water Needed

Some commercial farmers use soil moisture sensors placed at several locations and depths in their fields to which provide information on when and how much water to apply for specific vegetables and herbs. As an example, at the UMass Research Farm in Deerfield MA, we use soil moisture sensors called irrometers. We use irrometers both in open fields and in high tunnels, also known as unheated greenhouses (Figure 2). The plastic covering provides higher air temperatures, which increases crop yield, and also protects the plants from rain which drastically reduces issues with diseases and leaching - see the New England Vegetable Management Guide for information on high tunnels.

Some commercial farmers use soil moisture sensors placed at several locations and depths in their fields to which provide information on when and how much water to apply for specific vegetables and herbs. As an example, at the UMass Research Farm in Deerfield MA, we use soil moisture sensors called irrometers. We use irrometers both in open fields and in high tunnels, also known as unheated greenhouses (Figure 2). The plastic covering provides higher air temperatures, which increases crop yield, and also protects the plants from rain which drastically reduces issues with diseases and leaching - see the New England Vegetable Management Guide for information on high tunnels.

When the irrometer readings recommend irrigating, we apply the water (and fertilizer, when needed) using an injector that pushes the water and fertilizer through drip tape installed an inch below the soil surface. Applying water to the soil instead of to the foliage helps reduce leaf wetness and foliar disease development. See this video from the the Irromter company on installing an irrometer.

Soil water sensors such as irrometers are not commonly used in home gardens due to the cost and the wide variety of plants grown in a small area, each of which has different water requirements. In our work at our research farm we normally have one species, or multiple species of the same family, in a field and we can apply the same amount of water on the whole field. (As an example, in Figure 3, we have only one species of plant, ají dulce.)

Soil water sensors such as irrometers are not commonly used in home gardens due to the cost and the wide variety of plants grown in a small area, each of which has different water requirements. In our work at our research farm we normally have one species, or multiple species of the same family, in a field and we can apply the same amount of water on the whole field. (As an example, in Figure 3, we have only one species of plant, ají dulce.)

However, there are lower-tech options, more appropriate for home gardens, that can be used to irrigate your vegetables and herbs. For example, “<>soaker hoses” emit water throughout the length of the hose, gently distributing water onto the soil surface of the garden, leaving the above-ground parts of the plant dry. There are many types of soaker hoses available and information on different types is easily found online. (I don’t have an experience using them in my garden, for reasons I’ll describe below.)

In my garden, I irrigate with the use of an <>oscillating sprinkler in combination with a watering can, depending on the situation:

In my garden, I irrigate with the use of an <>oscillating sprinkler in combination with a watering can, depending on the situation:

- When I direct-seed a vegetable or herb into the soil, which I do all season long, I will make sure the soil where I seed is sufficiently moist but not soaked. Seeds need to absorb (or imbibe) water in order to germinate. Depending on the weather, I may have to water the soil multiple times where I direct-seeded to ensure the moisture is sufficient to promote germination. I use a watering can (Figure 4) so I don’t irrigate other parts of the garden that don’t need it. Applying water to plants that don’t need it is a waste of water and can cause nutrient leaching and increase the potential for diseases.

- After plants emerge through the soil surface after being seeded, they may need more frequent watering, but with lower amounts than more established plants in the garden since the roots of the recently emerged seedlings, where most of the water enters the plant, emerge slowly and it takes time for them to expand in order to take up sufficient amounts of water for optimum growth.

- Transplanted vegetables and herbs need much more water after transplanting than plants that were direct-seeded. Make sure the transplants are well-watered before transplanting. I then water the transplants aggressively once they are in the soil, to assist in root expansion. I then water them daily for a few days, depending on the temperature and moisture in the soil, with the goal of keeping the soil surrounding the transplant root ball moist. I try to apply the water to the base of the transplant so the leaves and the rest of the plant do not get wet, which can encourage disease.

- When I water the whole garden, which I do when it is very dry, I use an oscillating sprinkler (Figure 4) that reaches all plants in the garden. I realize this breaks some of the recommendations above, such as trying not to get the leaves wet and paying attention to different amounts of water needed for different species and plant maturities, but there are times when I don’t have time to individually water plants at different stages. When I do water the whole garden with the oscillating sprinkler, I try to do so earlier in the day so the above-ground parts of the plants will have time to dry off before nightfall, which decreases the time plant parts are wet and lessens potential for disease onset.