UMass Extension's Landscape Message is an educational newsletter intended to inform and guide Massachusetts Green Industry professionals in the management of our collective landscape. Detailed reports from scouts and Extension specialists on growing conditions, pest activity, and cultural practices for the management of woody ornamentals, trees, and turf are regular features. The following issue has been updated to provide timely management information and the latest regional news and environmental data.

The Landscape Message will be updated once in October. The next message will be posted on October 7. To receive immediate notification when the next Landscape Message update is posted, be sure to join our e-mail list

To read individual sections of the message, click on the section headings below to expand the content:

Scouting Information by Region

Environmental Data

The following data was collected on or about September 21, 2022. Total accumulated growing degree days (GDD) represent the heating units above a 50º F baseline temperature collected via regional NEWA stations (http://newa.cornell.edu) for the 2022 calendar year. This information is intended for use as a guide for monitoring the developmental stages of pests in your location and planning management strategies accordingly.

|

MA Region/Location |

GDD |

Soil Temp |

Precipitation |

Time/Date of Readings |

|||||

|

2-Week Gain |

2022 Total |

Sun |

Shade |

||||||

|

CAPE |

229 | 2599 | 67 | 65 | 1.01 |

12:00 PM 9/21 |

|||

|

SOUTHEAST |

220 | 2718.5 | 70 | 65 | 0.65 |

3:00 PM 9/21 |

|||

|

NORTH SHORE |

200 | 2626 | 62 | 59 | 0.52 |

10:30 AM 9/21 |

|||

|

EAST |

213 | 2892 | 68 | 66 | 0.58 |

5:00 PM 9/21 |

|||

|

METRO |

199 | 2702 | 60 | 59 | 0.53 |

6:00 AM 9/21 |

|||

|

CENTRAL |

202 | 2725 | 63 | 60 | 1.59 |

2:30 PM 9/21 |

|||

|

PIONEER VALLEY |

212 | 2727 | 68 | 63 | 1.16 |

12:00 PM 9/21 |

|||

|

BERKSHIRES |

181 | 2248 | 67 | 62 | 2.79 |

7:45 AM 9/21 |

|||

|

AVERAGE |

207 | 2654.5 | 65.5 | 62.5 | 1.10 |

_ |

|||

|

* = information not available |

|||||||||

As of 9/20, the entire state remained in stages of drought ranging from moderate to extreme: Massachusetts | U.S. Drought Monitor (unl.edu)

Phenology

| Indicator Plants - Stages of Flowering (BEGIN, BEGIN/FULL, FULL, FULL/END, END) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLANT NAME (Botanic / Common) | CAPE | S.E. | N.S. | EAST | METRO W. | CENT. | P.V. | BERK. |

|

Heptacodium miconioides (seven son flower) |

Full |

Full | Full | Full | Full | Full | Full | Full |

|

Clematis terniflora (sweet autumn Clematis) |

Full | Full | Full | Full | Full | Full | Full | Full |

|

Reynoutria japonica syn. Polygonum cuspidatum (Japanese knotweed) |

Full/End | Full/End | Full/End | Full |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End | Full/End |

| * = no activity to report/information not available | ||||||||

Regional Notes

Cape Cod Region (Barnstable)

General Conditions: The average temperature for the period from 9/7 through 9/21 was 67°F with a low of 45°F on Sept 16 and a high of 87°F on Sept 11. Overall, highs have been in the 70s, with a handful of days reaching 80°F and a couple of days with highs in the upper 60s. Nights have generally been warm, in the 60s, except for Sept 16 & 17 when lows dipped into the upper 40s. Conditions have been decent for outdoor work. In Barnstable precipitation fell on Sept. 12 and 13 amounting to just over an inch. Rainfall amounts across the area have been erratic with some areas approaching 3.0 inches during the same timeframe. Soil moisture is still dry and drought conditions persist. Some herbaceous plants seen in bloom include Phlox (Phlox paniculata), boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum), Russian sage (Salvia yangii), stonecrop ‘Autumn Joy’ (Hylotelephium), goldenrods (Solidago spp.) and some asters. Some woody plants in bloom include butterfly bush (Buddleia davidii), rose of Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus), crapemyrtle (Lagerstroemia indica) and Clerodendrum (Clerodendrum trichotomum).

Pests/Problems: Drought conditions are impacting plant health both in natural and man-made landscapes. Wilting, scorch, stress, premature leaf drop, early fall color and death can be seen. The drought is likely to have impacts on plant health well into next spring/early summer and beyond. Lawns are being repaired where possible; however, mandatory water restrictions are still in place limiting repairs. Cooler, shorter days and increased soil moisture have caused some plants to initiate new growth, not ideal going into fall. Fresh activity from turpentine beetle on pitch pine is still being seen. Many trees are likely to be attacked as a result of stress from drought and pine tip moth damage. Flagging as the result of black oak gall wasp damage has been seen in several areas of the mid-Cape. Some flagging on oak can also be seen as the result of fungal cankers (likely Botryosphaeria). Flagging causes can be differentiated by looking closely at twigs, flagging as a result of Botryosphaeria tends to be on the inner lower crown and flagging as a result of gall wasp on the upper outer crown. Other insects or insect damage seen during the period include leafminer damage on tupelo, fall webworm damage on tupelo and Callery pear, lacebug on Andromeda and azalea, two spotted spider mite on numerous plants, spruce spider mite damage on Alberta spruce, chili thrip damage on Hydrangea, and sunflower moth damage on Echinacea. Disease symptoms and signs seen during the period include pear trellis rust on Callery pear, Volutella blight on boxwood, black spot on rose, cedar apple rust on crabapple, Guignardia leaf blight on horsechestnut, Cercospora leaf spot on Hydrangea, foliar nematode on hosta and powdery mildew on just about any plant. Weeds seen in bloom include catsear (Hypochaeris radicata), Pennsylvania smart weed (Persicaria pensylvanica), purslane (Portulaca oleracea), horseweed (Conyza canadensis), carpetweed (Mollugo verticillata), perennial sow thistle (Sonchus arvensis), spotted spurge (Euphorbia maculata) and crabgrass. Yellow jackets and bald-faced hornets are more prominent as they actively search for food sources.

Southeast Region (Dighton)

General Conditions: The last gasp of summer has been decidedly like fall. Day temperatures have been as high as 79°F. Nights have been as low as 40°F. We've had frequent rain showers and thunderstorms. Overall, humidity increased and morning dew has been evident. Color can already be seen on poison ivy, burning bush, and swamp red maple. Lawns that survived the drought responded to the rain showers and more moderate temperatures and were once again in need of regular mowing. Apple and crabapple trees were heavy with fruit. Songbirds flocked and were busy searching for seeds and berries. Hummingbirds were still present. Hummingbird moths, monarch and tiger swallowtail butterflies were active. Crickets and katydids were quite vocal even during daylight hours. Mushrooms of all sorts were sprouting. Plants currently in flower: Ambrosia artemisiifolia (common ragweed), Buddleja davidii (butterfly bush), Campsis radicans (trumpet vine), Eupatorium perfoliatum (common boneset), Fallopia baldschuanica (silver lace vine), Franklinia alatamaha (Franklin tree), Helianthus tuberosus (Jerusalem artichoke), Hibiscus syriacus (rose of Sharon), Hosta spp. (plantain lily), Hydrangea paniculata (panicled Hydrangea), Hylotelephium telephium 'Autumn Joy' (syn. Sedum telephium), Lagerstroemia (crape myrtle), Miscanthus sinensis (Japanese silver grass), Phlox paniculata (garden Phlox), Rosa spp. (rose), Rudbeckia spp. (black-eyed-Susan), Salvia yangii (Russian sage), Solidago spp. (goldenrod), and Symphyotrichum ericoides (white heath aster).

Pests/Problems: Wasp and hornet nests have become sizable and the occupants are ornery. Remember to inspect areas for nests before working. Fall webworm nests were evident on oak and black cherry trees.

North Shore (Beverly)

General Conditions: HIgh temperatures typical of late summer have exited and it has finally started to feel like early fall. Daytime temperatures during this two week reporting period ranged from mid 60s to low 80s and nighttime temperatures ranged from low 40s to mid 60s. The average daily temperature was 64˚F with a minimum temperature of 42˚F recorded on September 17 and a maximum temperature of 82˚F recorded on September 10. Approximately 0.52 inches of rainfall were recorded at Long Hill during this two-week period. Due to the rains received during the last few weeks and the cooler night temperatures, turfgrasses on lawns and in landscapes are green and lush. Woody plants seen in bloom include: butterfly bush (Buddleia davidii), seven-son flower (Heptacodium miconioides), and rose-of-Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus). Herbaceous plants seen in bloom include: New England aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae), garden Phlox (Phlox paniculata), ‘Autumn Joy’ Sedum (Sedum telephium), black-eyed-Susan (Rudbeckia hirta), coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), Japanese Anemone (Anemone x hybrida), hardy Begonia (Begonia grandis), hardy Geranium (Geranium spp.), and autumn crocus (Colchicum autumnale). An assortment of annuals, including garden mums and dahlias, are also contributing color in landscapes.

Pests/Problems: Due to drought during the summer months some plants are showing signs of drought stress such as yellowing and browning, premature leaf drop and early foliage color change. Powdery mildew (Microsphaera alni) is still being observed on some lilac varieties. Leaf tip and marginal necrosis were observed on Stewartia (Stewartia sinensis). Crabgrass and other weeds are thriving in the landscape. Deer browsing was observed on some vegetable plants. Mosquitoes have slowed down but they are still active at dawn and dusk. Ticks are also active.

Pests/Problems: Due to drought during the summer months some plants are showing signs of drought stress such as yellowing and browning, premature leaf drop and early foliage color change. Powdery mildew (Microsphaera alni) is still being observed on some lilac varieties. Leaf tip and marginal necrosis were observed on Stewartia (Stewartia sinensis). Crabgrass and other weeds are thriving in the landscape. Deer browsing was observed on some vegetable plants. Mosquitoes have slowed down but they are still active at dawn and dusk. Ticks are also active.

East Region (Boston)

General Conditions: It has been feeling like early fall, despite the autumnal equinox occurring on the 22nd. Days are getting shorter; September 11 was our last sunset past 7 PM. Daytime temperatures averaged 74°F, while overnight lows averaged 57°F including two in the mid 40’s. We received 0.37 inches of rainfall overnight on the 19th, bringing us to 2.09 inches for September. Many lawns and gardens have greened up with renewed vigor. Several plants blooming in the landscape include; Caryopteris x clandonensis (bluebeard/blue spirea/blue mist), Eupatorium perfoliatum (common boneset), Helianthus tuberosus (Jerusalem artichoke), Heptacodium miconioides (seven son flower) and Solidago spp. (goldenrod). Several large colonies of woolly alder aphids (Prociphilus tessellatus) have been observed on speckled alder (Alnus incana). In addition to their intriguing appearance and life cycle, they provide an important food source for beneficials such as lacewings, lady beetles, the carnivorous larvae of the harvester butterfly, hover flies and beneficial wasps.

Pests/Problems: Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) is in full bloom. Roadside stands that had turned brown, seemingly suffering from drought stress, have begun resprouting from the base. Volutella blight has been observed on boxwood hedges. This opportunistic fungus Pseudonectria buxi has been infecting stressed boxwood (Buxus spp.) that in the past had successfully fought off the infection. The combined extremes of the growing season seem to have the landscape in confusion. Many herbaceous perennials are putting on new growth as if it were spring. Azaleas, Rhododendrons and Viburnum have been reblooming. Several poplars and birches experiencing early leaf drop are also leafing out at branch tips.

Metro West (Acton)

General Conditions: With the recent rain and cooler temperatures, lawns are greening up and plants are appearing to look less stressed than they had just a couple of weeks prior. The first day of autumn arrived on the 22nd of September and signs of this season are evident with fall foliage colors, shortened days, and cooler temperatures. September’s average rainfall is 3.77” and 3” of precipitation has been recorded for the month so far!! Observed in some stage of bloom this past week were the following woody plants: Aster spp. (New England Aster, New York Aster, smooth Aster, white wood Aster), Caryopteris x clandonensis (blue mist spirea), Chelone lyonii (pink turtlehead), Clematis terniflora (sweet autumn clematis), Franklinia alatahama (Franklin tree), Heptacodium miconioides (seven-son flower), Hibiscus moscheutos (swamp mallow), Kirengeshoma palmata (yellow wax bells), and Sedum spp. ‘Autumn Joy’ and ‘Rosy Glow’ (stonecrop).

Pests/Problems: As of September 8th, a Level D3 – Critical Drought had been declared for this area. With the 3” of rain received this month thus far, I anxiously await to see an updated drought report. The last report, according to the Massachusetts Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs showed that 100% of the Commonwealth was experiencing drought conditions.

Central Region (Boylston)

General Conditions: It’s finally starting to feel like fall! Average temperatures are rapidly falling to an average, moderate 64.8°F, with a high of 85.9°F and a low of 42.1°F in the last two weeks. Precipitation has, in turn, increased, reaching about 1.59 inches received in the two week reporting period. We've experienced several overcast days and a smattering of hot weather as well. Overall, the nights are cool, and the days are humid, but pleasantly warm. As fall approaches, burgeoning and vibrant fall foliage has stolen our attention. At the same time, many flowers in our region are fading. The following species, however, are in bloom: Hamamelis virginiana (common witch hazel), Symphyotrichum novae-angliae (New England Aster) and Solidago rugosa (rough goldenrod)—although somewhat waning. The following species are exhibiting fall foliage: Toxicodendron radicans (poison ivy), Cornus spp. (dogwoods), Acer rubrum (red maple), and Hydrangea quercifolia (oakleaf Hydrangea). The following weeks will be interesting, as shrubs and larger trees will continue to change color from summertime greens to subtler reds, oranges, etc. The region-wide drought has undoubtedly accelerated this process and the onset of fruit.

Pests/Problems: There are no pest problems to report. The symptoms of drought stress are still prevalent even after the latest respite from unforgiving temperatures. The leaf edges of shrubs and trees alike have turned yellow and are curling inwards. Hopefully the increased precipitation levels will help these plants carryover into the winter and spring seasons.

Pests/Problems: There are no pest problems to report. The symptoms of drought stress are still prevalent even after the latest respite from unforgiving temperatures. The leaf edges of shrubs and trees alike have turned yellow and are curling inwards. Hopefully the increased precipitation levels will help these plants carryover into the winter and spring seasons.

Pioneer Valley Region (Amherst)

General Conditions: Fall harvest is in full swing in the Connecticut River Valley as we officially transition to the autumn season. High temperatures have moderated in recent weeks, mostly hovering in the 70s and low 80s while nighttime temperatures have spanned the 50s and 60s. The long-term forecast calls for some further cooling as the growing season fades. There have been several rain events this month, which have helped to provide some relief to the drought that dominated the summer. Since the monster Labor Day storm, rainfall has occurred on 9/11–13 and 9/18–21 with accumulations over an inch in many areas. While more is needed to make up our annual deficit, the shorter days, cooler temperatures and decreasing sun angle is lessening transpirational demands. Fall color is starting to appear but for some trees, it signifies an early transition to dormancy due to drought stress. Winterberry (Ilex verticillata) berries are turning red and despite the name, their bright red display should be admired immediately. Some plants can be stripped clean by migrating birds in November and December. The rainfall and cooler temperatures this month have afforded excellent conditions for transplanting trees and shrubs. I’ve taken full advantage by installing several new plants in my own garden, including (but not limited to): Picea abies ‘Hillside Upright’, Chamaecyparis pisifera ‘Tsukumo’, and Pinus parviflora ‘Ryu-Jin’. After very little late summer activity, many fungi are now producing annual and perennial fruiting bodies. A range of mycorrhizal fungi are emerging in managed landscapes and forests, such as boletes, puffballs and agarics (several Amanita virosa, the destroying angel have been seen). Over the past 10 days, several destructive and common wood decay pathogens have been spotted across the UMass campus. These include (and are pictured below): Phaeolus schweinitzii on pitch pine (Pinus rigida), Ganoderma sessile on a badly declining sugar maple (Acer saccharum) and Cerioporus squamosus (formerly Polyporus squamosus) on a boxelder (A. negundo) with a large basal wound. The brown cubical root and butt rot pathogen, Phaeolus schweinitzii, is the most destructive decay pathogen of conifers in our region, attacking pine, spruce and larch. Annual fruiting bodies often first appear in early to mid-August, but were suppressed this year due to the dry conditions.

Pests/Problems: Turfgrasses have exhibited an impressive turnaround from the summer drought and many lawns are lush and growing at a rapid pace. Of course, some are overrun with crabgrass, which is quickly going to seed. Crabgrass seed can persist for up to seven years in the soil, making it a persistent problem for years to come. Skunk damage to turfgrass has been observed as they dig for grubs in the soil. Squirrels are doing damage to turf as well, burying acorns, hickory nuts and other winter stores. Squirrel activity is in overdrive right now, as they scavenge large tree canopies for nuts and seeds. Tiny seedlings of Oriental bittersweet are abundant right now in the landscape, especially under hedges and trees where birds regularly nest. These should be weeded immediately to ensure they don’t establish. Late season pathogen activity can ramp up with the increasing shade and lingering moisture that is common during the fall season. Foliar diseases of deciduous hardwoods cause little to no damage at this point, but their buildup can aid in overwintering and subsequent infection next spring. Stem and branch cankering fungi are also renewed at this time and blighted canopy parts should be identified and pruned immediately. Needle blight diseases, like Rhizosphaera needle cast of spruce, can also have a strong second act during the autumn season. When siting blue and white spruce, ensure excellent air flow and full sun. Other spruces (Norway, Oriental and Serbian) are more resistant and can be planted near infected blue spruce. However, if they become stressed by drought, winter injury, etc., they can be diseased as well.

Pests/Problems: Turfgrasses have exhibited an impressive turnaround from the summer drought and many lawns are lush and growing at a rapid pace. Of course, some are overrun with crabgrass, which is quickly going to seed. Crabgrass seed can persist for up to seven years in the soil, making it a persistent problem for years to come. Skunk damage to turfgrass has been observed as they dig for grubs in the soil. Squirrels are doing damage to turf as well, burying acorns, hickory nuts and other winter stores. Squirrel activity is in overdrive right now, as they scavenge large tree canopies for nuts and seeds. Tiny seedlings of Oriental bittersweet are abundant right now in the landscape, especially under hedges and trees where birds regularly nest. These should be weeded immediately to ensure they don’t establish. Late season pathogen activity can ramp up with the increasing shade and lingering moisture that is common during the fall season. Foliar diseases of deciduous hardwoods cause little to no damage at this point, but their buildup can aid in overwintering and subsequent infection next spring. Stem and branch cankering fungi are also renewed at this time and blighted canopy parts should be identified and pruned immediately. Needle blight diseases, like Rhizosphaera needle cast of spruce, can also have a strong second act during the autumn season. When siting blue and white spruce, ensure excellent air flow and full sun. Other spruces (Norway, Oriental and Serbian) are more resistant and can be planted near infected blue spruce. However, if they become stressed by drought, winter injury, etc., they can be diseased as well.

Berkshire Region (Great Barrington)

General Conditions: Dinah Washington sang “What a Diff’rence a Day Made”, but we in the Berkshires have another tune and that is “What a difference a month made”. September has brought an abrupt end to the drought conditions of summer. It has also brought much cooler temperatures. High temperatures over this recent scouting period at the 3 NEWA weather stations were quite similar and all on the same day. North Adams registered 82°F on September 10, Pittsfield had 80°F and Richmond reported 81°F. Likewise, minimum temperature occurred on the same day, September 16, at all three sites: 41°F in North Adams, 42°F in Pittsfield, and 40°F in Richmond. The mean temperature for the two weeks was 64.4°F for North Adams, 63.4°F for Pittsfield, and 63.5°F for Richmond. The best part of the weather this month has been the rain, though the amounts varied quite a lot throughout the county. Totals from Sept. 1 to Sept. 21 are: 4.83 inches in North Adams, 4.29 inches for Pittsfield, and 3.58 inches for Richmond. However, there were unofficial reports of much greater amounts in other towns. Here in West Stockbridge, my rain gauge collected 6.07 inches. Similar or a bit higher amounts were reported further south in the County. For the recent 2 week scouting period the totals were: 2.79 inches in West Stockbridge, 2.64 inches in North Adams, 1.76 inches in Pittsfield, and 1.60 inches in Richmond. Still, year to date rainfall is around 2 inches in deficit. Currently soils are quite moist but not water logged. All of these conditions bode well for the health and winter survival of woody plants and herbaceous perennials. Some foliage color change is noticeable already but as yellow-green rather than brighter colors. There are a large number of trees that are sparsely foliated at this time. This is most often true of species defoliated by spongy moth caterpillars this past spring and summer. Turfgrass, some of which had gone dormant this summer, has responded to the increased moisture and is growing green and well. Fall flowering perennials are looking very good at this time. One of the joys of autumn is Autumn Joy, the late summer/early fall blooming autumn crocus; not a true crocus but is of the genus Colchicum. Its message is clear: enjoy autumn.

Pests/Problems: Plant pests, other than slugs and snails, are very few at this time and are most often in their winter prep stage as eggs or settled mature insects. Overall, the population of the Asian jumping worm was much less this year, perhaps due to the drought conditions. They seem to be a little more visible now but still at numbers much lower than in 2021. It is likely that the drought conditions this year account for much of the early leaf drop now happening. As mentioned above, there are many trees either sparsely defoliated or totally defoliated. Many apple and crabapple trees are among these, but their sparse foliation is mostly due to cedar apple rust and apple scab. The rabbit population seems quite high and feeding damage to herbaceous perennials is frequently reported. Peony diseases, i.e. stem and leaf blight, are quite visible at this time as is powdery mildew on a wide range of plants.

Regional Scouting Credits

- CAPE COD REGION - Russell Norton, Horticulture and Agriculture Educator with Cape Cod Cooperative Extension, reporting from Barnstable.

- SOUTHEAST REGION - Brian McMahon, Arborist, reporting from the Dighton area.

- NORTH SHORE REGION - Geoffrey Njue, Green Industry Specialist, UMass Extension, reporting from the Long Hill Reservation, Beverly.

- EAST REGION - Kit Ganshaw & Sue Pfeiffer, Horticulturists reporting from the Boston area.

- METRO WEST REGION – Julie Coop, Forester, Massachusetts Department of Conservation & Recreation, reporting from Acton.

- CENTRAL REGION - Mark Richardson, Director of Horticulture reporting from New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill, Boylston.

- PIONEER VALLEY REGION - Nick Brazee, Plant Pathologist, UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab, reporting from Amherst.

- BERKSHIRE REGION - Ron Kujawski, Horticultural Consultant, reporting from Great Barrington.

Woody Ornamentals

Diseases

Recent pests and pathogens of interest seen in the UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab, a select few:

- Foliar scorch of a weeping Japanese maple (Acer palmatum) caused by exposure and maple anthracnose (Aureobasidium apocryptum). This laceleaf cultivar is approximately 15-years-old and resides in a raised planter within an urban courtyard. The tree experiences partial sun and receives drip irrigation. However, exposure from heat and winds in a large container has posed a challenging environment for this tree. The finely dissected leaves submitted to the lab were brown and desiccated on the margins. Anthracnose fungi will readily colonize foliage suffering from abiotic stress and this appears to be the case here. Japanese maples grow very well in containers but exposure is always a threat to good overall health.

- Infestation of the redheaded pine sawfly (Neodiprion lecontei) and pine needle scale (Chionaspis pinifoliae) on mugo pine (Pinus mugo). The tree is approximately 10-years-old and resides in a full sun garden with drip irrigation. The current season’s (2022) needles were stripped on the terminal shoots by feeding from the adult larvae. Early instar feeding from earlier in the summer appeared as brown, curled and stunted needles on last year’s (2021) growth. The redheaded pine sawfly is a native insect pest that targets two- and three-needle pines. A variety of insect predators will feed on the young larvae, keeping populations in check on certain plants. At times, however, populations outpace predation and significant damage is done to landscape pines. The pine needle scale infestation was moderate in severity, with a number of bright white, elongated scales readily observable on the dark green needles. On these needles, yellow, chlorotic spots (flecking) were evident, as is typical for pines infested with armored scales.

- Pear trellis rust, caused by Gymnosporangium sabinae, on Bradford pear (Pyrus calleryana). The tree is roughly 15-years-old and was part of a group planting at a housing development. The trees receive full sun and receive some supplemental water through lawn irrigation. Over the past two years, large spots and blotches have appeared on the foliage, mostly along the midrib and scattered throughout the canopies. These very large spots are typical of G. sabinae, and when they develop on the petiole, trees can shed large volumes of leaves in mid-summer. Tan to brown-colored, raised masses form on the underside of the spots, which serve to disperse spores (aeciospores). Like many Gymnosporangium species, the pear trellis rust pathogen also needs to infect Juniperus to complete its life cycle.

- Shoot tip dieback of Oriental spruce (Picea orientalis) caused by Phomopsis. The tree is approximately 30-years-old and occupies a full sun, open lawn area that is exposed to the elements. The submitted branch segments exhibited blighted shoot tips with brown, shedding needles while the growth appeared relatively healthy. The symptoms developed mid-summer and while the tree is exposed to lawn irrigation, drought stress may have facilitated disease development.

Report by Nick Brazee, Plant Pathologist, UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab, UMass Amherst.

Insects

An Update about Neonicotinoid Use in Massachusetts:

Beginning July 1, 2022 systemic insecticide active ingredients known as neonicotinoids have become state restricted use for tree and shrub uses in Massachusetts. If an individual works in the commercial industry (landscapers, arborists, etc.), then a Commercial Certification License is needed. (Example: Category 36 Commercial Certification License, Shade Trees & Ornamentals.) Someone can use a state or federal restricted use pesticide if they have a Commercial Applicators License as long as they are working under the direct supervision of someone with a Commercial Certification. Unlicensed or uncertified individuals will no longer be able to apply neonicotinoids to manage insect pests of trees and shrubs in Massachusetts.

More information is available, here: https://www.mass.gov/service-details/pesticide-newsupdates

Helpful Information from Taryn LaScola-Miner, Director, Crop and Pest Services Division of the MA Department of Agricultural Resources:

“As you know, products that contain neonicotinoids and have certain use patterns will have a classification change from General Use to Restricted Use on July 1, 2022. In order to help inform the manufacturers, dealers, sellers and applicators of which products will be changing from general use to restricted use, the Department has created the list of neonicotinoid products that currently are and will become restricted use beginning July 1st. You may find the list at the link below. Please note that this list is subject to change.

Additionally, MDAR is anticipating that there will be more of a need for companies to follow the Direct Supervision regulations with this change. Therefore, MDAR has updated its Direct Supervision Frequently Asked Questions document as well.

Although an email will be sent to all licensed applicators within the next few weeks as a final reminder of the change, please pass this information along to your members and customers as an effort to make this transition as smooth as possible. If you have any questions, please let me know. Thank you!”

List of Neonicotinoid Products: https://www.mass.gov/doc/list-of-neonicotinoid-pesticides/download

Direct Supervision Frequently Asked Questions: https://www.mass.gov/doc/direct-supervision-frequently-asked-questions-faq/download

Insects and Other Arthropods

-

Mosquitoes: The Massachusetts Department of Public Health (DPH) announced on 7/13/2022 that West Nile virus (WNV) had been detected in mosquitoes in Massachusetts for the first time in 2022. The presence of WNV was confirmed by the Massachusetts State Public Health Laboratory in a mosquito sample collected July 11 in the town of Easton, MA in Bristol County. More information about this detection is available here: https://www.mass.gov/news/state-public-health-officials-announce-seasons-first-west-nile-virus-positive-mosquito-sample-3 Since then, additional mosquito samples have tested positive for the virus (WNV). On 9/2/2022 state health officials announced a second human case of West Nile Virus in Massachusetts for 2022: https://www.mass.gov/news/state-health-officials-announce-second-human-case-of-west-nile-virus-in-massachusetts-1 . Since then, additional mosquito samples have tested positive for the virus (WNV). On 9/8/2022 state health officials announced a fourth human case of West Nile Virus in Massachusetts for 2022: https://www.mass.gov/news/state-health-officials-announce-fourth-human-case-of-west-nile-virus-in-massachusetts . As of 9/21/2022, no eastern equine encephalitis (EEE) positive mosquito samples, human cases, or animal cases have been detected or reported by DPH.

According to the Massachusetts Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Science and the Department of Public Health, there are at least 51 different species of mosquito found in Massachusetts. Mosquitoes belong to the Order Diptera (true flies) and the Family Culicidae (mosquitoes). As such, they undergo complete metamorphosis, and possess four major life stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Adult mosquitoes are the only stage that flies and many female mosquitoes only live for 2 weeks (although the life cycle and timing will depend upon the species). Only female mosquitoes bite to take a blood meal, and this is so they can make eggs. Mosquitoes need water to lay their eggs in, so they are often found in wet or damp locations and around plants. Different species prefer different habitats. It is possible to be bitten by a mosquito at any time of the day, and again timing depends upon the species. Many are particularly active from just before dusk, through the night, and until dawn. Mosquito bites are not only itchy and annoying, but they can be associated with greater health risks. Certain mosquitoes vector pathogens that cause diseases such as West Nile virus (WNV) and eastern equine encephalitis (EEE). For local risk levels of WNV and EEE based on state sampling, visit: https://www.mass.gov/info-details/massachusetts-arbovirus-update.

For more information about mosquitoes in Massachusetts, visit: https://www.mass.gov/service-details/mosquitoes-in-massachusetts

There are ways to protect yourself against mosquitoes, including wearing long-sleeved shirts and long pants, keeping mosquitoes outside by using tight-fitting window and door screens, and using insect repellents as directed. Products containing the active ingredients DEET, permethrin, IR3535, picaridin, and oil of lemon eucalyptus provide protection against mosquitoes. Be aware that not all of these can be safely used on young children. Read and follow all label instructions for safety and proper use.

For more information about mosquito repellents, visit: https://www.mass.gov/service-details/mosquito-repellents and https://www.cdc.gov/mosquitoes/mosquito-bites/prevent-mosquito-bites.html .

-

Deer Tick/Blacklegged Tick: Ixodes scapularis adults are active all winter and spring, as they typically are from October through May, and “quest” or search for hosts at any point when daytime temperatures are above freezing. Engorged females survive the winter and will lay 1,500+ eggs in the forest leaf litter beginning around Memorial Day (late May). Larvae are encountered in New England from roughly May through November, with peak risk reported in August. Nymphs are encountered from April through July with a peak risk reported in June in New England. Nymphs may also be encountered again in October and November. For images of all deer tick life stages, along with an outline of the diseases they carry, visit: https://web.uri.edu/tickencounter/species/blacklegged-tick/ .

Anyone working in the yard and garden should be aware that there is the potential to encounter deer ticks. The deer tick or blacklegged tick can transmit Lyme disease, human babesiosis, human anaplasmosis, and other diseases. Preventative activities, such as daily tick checks, wearing appropriate clothing, and permethrin treatments for clothing (according to label instructions) can aid in reducing the risk that a tick will become attached to your body. If a tick cannot attach and feed, it will not transmit disease. For more information about personal protective measures, visit: https://web.uri.edu/tickencounter/prevention/protect-yourself/

The Center for Agriculture, Food, and the Environment provides a list of potential tick identification and testing resources here: https://ag.umass.edu/resources/tick-testing-resources .

-

Wasps/Hornets: Many wasps are predators of other arthropods, including pest insects such as certain caterpillars that feed on trees and shrubs. Adult wasps hunt prey and bring it back to their nest where young are being reared, as food for the immature wasps. A common such example are the paper wasps (Polistes spp.) who rear their young on chewed up insects. They may be seen searching plants for caterpillars and other soft-bodied larvae to feed their young. Paper wasps can sting, and will defend their nests, which are open-celled paper nests that are not covered with a papery “envelope”. These open-celled nests may be seen hanging from eaves or other outdoor building structures. Aerial yellow jackets and hornets create large aerial nests that are covered with a papery shell or “envelope”. Common yellow jacket species include those in the genus Vespula. Dolichovespula maculata is commonly known as the baldfaced hornet, although it is not a true hornet. The European hornet (Vespa crabro) is three times the size of a yellow jacket and may be confused for the northern* giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia). The European hornet is known to Massachusetts, but the northern giant hornet is not. If you are concerned that you have found or photographed a northern giant hornet, please report it here: https://massnrc.org/pests/report.aspx . A helpful ID tool, although developed for Texas by the USDA, depicts common look-a-like species that we also have in MA that can be confused for the northern giant hornet and is found here: https://agrilife.org/lubbock/files/2020/05/Asian_Giant_Hornet_Look-alikes_101_Xanthe_Shirley.pdf . Paper wasps and aerial yellowjackets overwinter as fertilized females (queens) and a single female produces a new nest annually in the late spring. Queens start new nests, lay eggs, and rear new wasps to assist in colony/nest development. Nests are abandoned at the end of the season. Some people are allergic to stinging insects, so care should be taken around wasp/hornet nests. Unlike the European honeybee (Apis mellifera), wasps and hornets do not have barbed stingers, and therefore can sting repeatedly when defending their nests. It is best to avoid them, and if that cannot be done and assistance is needed to remove them, consult a professional.

*For more information about the recent common name change for Vespa mandarinia, please visit: https://entsoc.org/news/press-releases/northern-giant-hornet-common-name-vespa-mandarinia

Woody ornamental insect and non-insect arthropod pests to consider, a selected few:

Invasive Insects & Other Organisms Update:

-

Spotted Lanternfly: (Lycorma delicatula, SLF) is a non-native, invasive insect that feeds on over 103 species of plants, including many trees and shrubs that are important in our landscapes.

Spotted Lanternfly: (Lycorma delicatula, SLF) is a non-native, invasive insect that feeds on over 103 species of plants, including many trees and shrubs that are important in our landscapes.

In the beginning of August 2022, the MA Department of Agricultural Resources (MDAR) announced an additional detection of an established population of the spotted lanternfly in Springfield, MA. MDAR is urging the public to be on the lookout for this pest, especially if they live or work in the Springfield area, and to report it immediately. For more information about the detection in Springfield, visit: https://www.mass.gov/news/state-agricultural-officials-ask-residents-to-report-sightings-of-the-invasive-spotted-lanternfly . In September 2022, the city of Worcester, MA announced a small, satellite population of the spotted lanternfly was confirmed by MDAR in Worcester: https://www.worcesterma.gov/announcements/residents-asked-to-report-sightings-of-invasive-spotted-lanternfly-recently-detected-in-worcester .

Currently, the only established populations of spotted lanternfly in Massachusetts are in Fitchburg, Shrewsbury, and Worcester, MA (Worcester County) and Springfield, MA (Hampden County). Therefore, there is no reason to be preemptively treating for this insect in other areas of Massachusetts. If you suspect you have found spotted lanternfly in additional locations, please report it immediately to MDAR here: https://massnrc.org/pests/slfreport.aspx . If you are living and working in the Fitchburg, Shrewsbury, and Springfield areas, please be vigilant and continue to report anything suspicious. If you are living and working in the Fitchburg, Shrewsbury, Worcester, and Springfield areas, please be vigilant and continue to report anything suspicious.

For More Information:

From UMass Extension:

Check out the InsectXaminer Episode about spotted lanternfly adults and egg masses! Available here: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/insectxaminer

Fact Sheet: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/spotted-lanternfly

*NEW*: Center for Agriculture, Food, and the Environment: https://ag.umass.edu/news-events/highlights/spotting-spotted-lanternfly

From the MA Department of Agricultural Resources:

Fact Sheet and Map of Locations in MA: https://massnrc.org/pests/pestFAQsheets/spottedlanternfly.html

-

Asian Longhorned Beetle: (Anoplophora glabripennis, ALB) Look for signs of an ALB infestation which include perfectly round exit holes (about the size of a dime), shallow oval or round scars in the bark where a female has chewed an egg site, or sawdust-like frass (excrement) on the ground nearby host trees or caught in between branches. Be advised that other, native insects may create perfectly round exit holes or sawdust-like frass, which can be confused with signs of ALB activity.

The regulated area for Asian longhorned beetle is 110 square miles encompassing Worcester, Shrewsbury, Boylston, West Boylston, and parts of Holden and Auburn. If you believe you have seen damage caused by this insect, such as exit holes or egg sites, on susceptible host trees like maple, please call the Asian Longhorned Beetle Eradication Program office in Worcester, MA at 508-852-8090 or toll free at 1-866-702-9938.

To report an Asian longhorned beetle find online or compare it to common insect look-alikes, visit: http://massnrc.org/pests/albreport.aspx or https://www.aphis.usda.gov/pests-diseases/alb/report .

-

Brown Marmorated Stink Bug: (Halyomorpha halys; BMSB) is a non-native insect first detected in the United States in 1998 in Allentown, PA. This insect was accidentally introduced from Asia. It was first detected in MA in 2007. It has since been reported in multiple counties of MA, but at this time, BMSB is not yet a significant pest of agricultural crops in Massachusetts as it has been in other areas of the United States. BMSB attacks a broad variety of plants, including fruit crops and shade trees. Host plants include but are not limited to: peach, apple, pear, maples, dogwoods, butterfly bush, and vegetable crops. More comprehensive list of hosts.

. Brown marmorated stink bugs can be distinguished from native stink bugs by the white bands on the antennae and alternating white and dark bands at the rear edge of the abdomen. Adults emerge around April from their overwintering locations. Females can lay approximately 500 eggs during their lifetime, in clusters of 30 eggs or so at a time, roughly from June-August. Eggs hatch and the immature insects (the nymphs) undergo 5 instars. Adults can be nuisance insects as they become fall home invaders, roughly by the end of September and into October, seeking sheltered locations to overwinter.

-

Browntail Moth: Euproctis chrysorrhoea is an invasive insect originating from Europe and first detected in the US in Somerville, MA in 1897. Currently, browntail moth is limited to a small portion of eastern Massachusetts, particularly areas near the coast. Report suspected browntail moth life stages.

. Due to a persistent outbreak of this insect in Maine since approximately 2016, it is a good idea for us to again familiarize ourselves with this pest.

View a great update on the current status of browntail moth in Maine, including excellent photos of newly hatched browntail moth caterpillars compared to a common lookalike (fall webworm).

Caution: hairs found on the caterpillar and pupal life stages of this insect can cause a rash similar to poison ivy. Some individuals are very sensitive to browntail moth hairs and may also experience allergic reaction. The chance of interacting with browntail moth hairs increases between May and July, although they could be a problem at any time of year.

The larval or caterpillar stage of this insect is present from August until the following June (spending the winter in webs they create on the tips of host plant twigs). In the fall, groups of caterpillars are found creating webs around a tightly wrapped leaf (covered in bright white silk) where they will overwinter in groups of 25-400. These 2-4 inch long webs can be found on the ends of branches often on apple or red oak. As soon as leaves begin to open in the spring (usually by April), the caterpillars will crawl from their webs to feed on the new leaves. Caterpillars are fully grown around June and spin cocoons in which they pupate. These cocoons are also full of the irritating hairs and should be dealt with extreme caution. Adult moths emerge in July and females lay eggs on the undersides of leaves in masses of 200-400, covering them with hairs from their bodies. (Adults do not typically cause skin rashes.) Eggs hatch around August and September and larvae feed shortly before forming their overwintering webs.

The primary concern with this insect are the poisonous hairs found on the caterpillars. Contact with the caterpillar or its hairs can cause a rash similar to poison ivy in susceptible individuals. If hairs break off and blow around in the wind, they can cause difficulty breathing and headaches. While this insect can act as a defoliator in the larval stage, feeding on the leaves of many deciduous trees and shrubs, this activity may be secondary to concerns about public health risks. Care should be taken to avoid places infested with these caterpillars, exposed skin or clothing should be washed, and the appropriate PPE should be worn if working with these insects. Consult your physician if you have a reaction to the browntail moth.

-

Emerald Ash Borer: (Agrilus planipennis, EAB) has been detected in at least 11 out of the 14 counties in Massachusetts. A map of these locations across the state. Additional information about this insect is provided by the MA Department of Conservation and Recreation.

Emerald Ash Borer: (Agrilus planipennis, EAB) has been detected in at least 11 out of the 14 counties in Massachusetts. A map of these locations across the state. Additional information about this insect is provided by the MA Department of Conservation and Recreation.

This wood-boring beetle readily attacks ash (Fraxinus spp.) including white, green, and black ash and has also been found developing in white fringe tree (Chionanthus virginicus) and has been reported in cultivated olive (Olea europaea). Signs of an EAB infested tree may include D-shaped exit holes in the bark (from adult emergence), “blonding” or lighter coloration of the ash bark from woodpecker feeding (chipping away of the bark as they search for larvae beneath), and serpentine galleries visible through splits in the bark, from larval feeding beneath. It is interesting to note that woodpeckers are capable of eating 30-95% of the emerald ash borer larvae found in a single tree (Murphy et al. 2018). Unfortunately, despite high predation rates, EAB populations continue to grow. However, there is hope that biological control efforts will eventually catch up with the emerald ash borer population and preserve some of our native ash tree species for the future. For an update about the progress of the biological control of emerald ash borer, visit Dr. Joseph Elkinton’s archived 2022 webinar.

-

Jumping Worms: Amynthas spp. earthworms, collectively referred to as “jumping or crazy or snake” worms, overwinter as eggs in tiny, mustard-seed sized cocoons found in the soil or other substrate (ex. compost) that are impossible to remove. The first adults appear in the end of May – June, but the numbers are low and infestations are rarely noticed at that time. It is easy to misidentify earthworms if only immatures found. By August and September, this is when most observations of fully mature jumping worms occur. At that time, snake worms become quite abundant, infestations become very noticeable, and may cause a lot of concern for property owners and managers.

For More Information:

UMass Extension Fact Sheets:

*NEW* Resource with Over 70 Questions and their Answers: Invasive Jumping Worm Frequently Asked Questions

Earthworms in Massachusetts – History, Concerns, and Benefit

Jumping/Crazy/Snake Worms – Amynthas spp.

A Summary of the Information Shared at UMass Extension’s Jumping Worm Conference in January 2022

Tree & Shrub Insect Pests, Continued:

Ailanthus Webworm: Atteva aurea (formerly A. punctella) is a tropical ermine moth from the family Attevidae. While they may be referred to as tropical, apparently the moths themselves can tolerate much colder temperatures than their original host plants. Prior to 1784 when tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) was introduced into Philadelphia, PA, the ailanthus webworm was restricted to southern Florida and points south. It would appear that this restriction in distribution was due to the distribution of their original host plants in the genus Simarouba. Once the tree of heaven’s range extended from the north to the south including Florida, the moths were able to move northward on the newly available and suitable host plant. Larvae of this moth feed almost exclusively on tree of heaven in the northern parts of its expanded range. Occasionally, these caterpillars will defoliate tree of heaven, but not to the extent that they could provide any form of control of this invasive tree. (On younger plants, sometimes caterpillars can completely defoliate the trees and strip the bark off of small branches.) Larvae cluster together in a loose web. Larvae of the ailanthus webworm have five white longitudinal lines on an olive-brown colored base with sparsely hairy bodies. Caterpillars are found in the late summer. Larvae pupate within their webs, moths emerge, mate, and then lay their eggs on the outside of the webs. Multiple, overlapping generations can occur per year. These mating ailanthus webworm moths were seen on 8/25/2022 in Springfield, MA.

Ailanthus Webworm: Atteva aurea (formerly A. punctella) is a tropical ermine moth from the family Attevidae. While they may be referred to as tropical, apparently the moths themselves can tolerate much colder temperatures than their original host plants. Prior to 1784 when tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) was introduced into Philadelphia, PA, the ailanthus webworm was restricted to southern Florida and points south. It would appear that this restriction in distribution was due to the distribution of their original host plants in the genus Simarouba. Once the tree of heaven’s range extended from the north to the south including Florida, the moths were able to move northward on the newly available and suitable host plant. Larvae of this moth feed almost exclusively on tree of heaven in the northern parts of its expanded range. Occasionally, these caterpillars will defoliate tree of heaven, but not to the extent that they could provide any form of control of this invasive tree. (On younger plants, sometimes caterpillars can completely defoliate the trees and strip the bark off of small branches.) Larvae cluster together in a loose web. Larvae of the ailanthus webworm have five white longitudinal lines on an olive-brown colored base with sparsely hairy bodies. Caterpillars are found in the late summer. Larvae pupate within their webs, moths emerge, mate, and then lay their eggs on the outside of the webs. Multiple, overlapping generations can occur per year. These mating ailanthus webworm moths were seen on 8/25/2022 in Springfield, MA.

Bagworm: Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis is a native species of moth whose larvae construct bag-like coverings over themselves with host plant leaves and twigs. Look for caterpillars with cone-like coverings of chewed up leaves, bark, and other plant parts. Common bagworm may be found on evergreen and deciduous host plants. More information about bagworm.

Bagworm: Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis is a native species of moth whose larvae construct bag-like coverings over themselves with host plant leaves and twigs. Look for caterpillars with cone-like coverings of chewed up leaves, bark, and other plant parts. Common bagworm may be found on evergreen and deciduous host plants. More information about bagworm.

.

These caterpillars develop into moths as adults. Their behaviors, life history, and appearance are interesting. The larvae (caterpillars) form “bags” or cases over themselves as they feed using assorted bits of plant foliage and debris tied together with silk. As the caterpillars feed and grow in size, so does their “bag”. Young, early instar caterpillars may feed with their bag oriented skyward, skeletonizing host plant leaves. As these caterpillars grow in size, they may dangle downward from their host plant, and if feeding on a deciduous host, they can consume the leaves down to the leaf veins. Pupation can occur in southern New England in late September or into October and this occurs within the “bag”. Typically, this means that the caterpillars could encounter a killing frost and die before mating could occur. However, in warmer areas of Massachusetts or if we experience a prolonged, warm autumn, it is possible for this insect to overwinter and again become a problem the following season. Bagworm caterpillars are now large and have done much of their feeding for the season in Massachusetts. Mature caterpillars have been reported in Amherst, MA (8/24/2022) and East Bridgewater, MA (8/28/2022). If the larvae survive to pupation, adult male moths emerge and are winged, able to fly to their flightless female mates. The adult male is blackish in color with transparent wings. The female is worm-like; she lacks eyes, wings, functional legs, or mouthparts. The female never gets the chance to leave the bag she constructs as a larva. The male finds her, mates, and the female moth develops eggs inside her abdomen. These eggs (500-1000) overwinter inside the deceased female, inside her bag, and can hatch roughly around mid-June in southern New England. Like other insects with flightless females, the young larvae can disperse by ballooning (spinning a silken thread and catching the wind to blow them onto a new host).

While arborvitae and junipers can be some of the most commonly known host plants for this insect, the bagworm has a broad host range including both deciduous and coniferous hosts numbering over 120 different species. Bagworm has been observed on spruce, Canaan fir, honeylocust, oak, European hornbeam, rose, and London planetree among many others. This insect can be managed through physical removal, if they can be safely reached. Squeezing them within their bags or gathering them in a bucket full of soapy water (or to crush by some other means) can be effective ways to manage this insect on ornamental plants. Early instar bagworm caterpillars can be managed with Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki (Btk) but this is most effective on young bagworms that are approximately no larger than ¾ inch in length. As bagworms grow in size, they may also have behavioral mechanisms for avoiding chemical management. At this point in the season, physical removal (if possible) may be the best option. This will also preserve any natural enemies that would be found attacking this insect, such as certain parasitic wasps. It is also important to note that the bags from dead bagworms will remain on the host plant, so check the viability of the bagworms by dissecting their bags to avoid unnecessary chemical applications. Historically in Massachusetts, bagworms have been mostly a problem coming in on infested nursery stock. With females laying 500-1000 eggs, if those eggs overwinter the population can grow quite large in a single season on an infested host. Typically, this insect becomes a problem on hedgerows or plantings nearby an infested host plant. Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis is found from Massachusetts to Florida, and is typically a more significant pest in southern climates. However, in recent years (2019-2021), bagworm appears to be overwintering successfully in certain locations in Massachusetts.

-

Black Turpentine Beetle: Dendroctonus terebrans adults may begin to be active between mid-April to mid-May, however all life stages, including adults, of this insect may be found throughout the season. Host plants include: black pine (Pinus thunbergiana), eastern white pine (Pinus strobus), Japanese black pine (Pinus thunbergii), loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), pitch pine (Pinus rigida), red spruce (Picea rubens), Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), and slash pine (Pinus elliottii).

Black Turpentine Beetle: Dendroctonus terebrans adults may begin to be active between mid-April to mid-May, however all life stages, including adults, of this insect may be found throughout the season. Host plants include: black pine (Pinus thunbergiana), eastern white pine (Pinus strobus), Japanese black pine (Pinus thunbergii), loblolly pine (Pinus taeda), pitch pine (Pinus rigida), red spruce (Picea rubens), Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), and slash pine (Pinus elliottii).

Black turpentine beetle adults and larvae from samples collected in Barnstable County were recently submitted to the UMass Plant Diagnostics Laboratory for identification. This insect is in the same genus as the southern pine beetle (Dendroctonus frontalis) but some useful features and behaviors can be used in the field to distinguish the two from one another. First, the black turpentine beetle (5-8 mm or 5-10 mm are reported in the literature.) has much larger adults than the southern pine beetle (2-3 mm.). Second, the black turpentine beetle tends to limit its attacks of the trunk of its host plants to the lower 6 ft., whereas southern pine beetle caused popcorn-like pitch tubes may be found throughout the entire trunk of the tree. The photos included here show the pitch tubes created by black turpentine beetle activity on the lower trunk of the infested trees. (Photos courtesy of Chad Thomas, 8/18/2022, Barnstable County.)

This is one of the largest native North American bark beetles. In the northern parts of its extensive range, the black turpentine beetle overwinters as an adult in the bark of its hosts. In the southern portions of its range, all life stages may be present throughout the year. As mentioned above, egg laying and feeding is usually kept to the basal 6 feet of the host plant. Mated pairs of adult beetles work to excavate galleries that may be 9.8 inches wide and 11.8 inches long. 100-200 eggs may be laid on one side of the gallery. Once hatched, larvae feed in groups on the inner bark. Fully grown larvae are legless, white, and almost 1/2 inch in length. Pupation occurs and adults eventually emerge from the bark to re-infest the same tree, or disperse to another susceptible host.

Stumps and buttress roots of freshly cut trees are favored by this insect. Attacked trees may exhibit browning of needles and oozing of large masses of pitch. Masses of pitch (pitch tubes) may cover holes in the trunk and may be considerably larger than those of southern pine beetle. Pitch hardens and is first white but may turn red as it ages. Pitch is irregular in shape and up to 1.6 inches in diameter. Pitch tubes are not visible when the area below the soil line is attacked. Healthy trees are usually not attacked, however it has been reported on occasion.

Check drought-stressed or otherwise stressed trees for needles turning light green to rust color. Drought-stressed trees, such as what is so common currently, may be more susceptible to bark beetle attack, including from black turpentine beetle. Also avoid pruning and removal of host plants during the growing season, as these activities can be additionally attractive to the black turpentine beetle. Unless it is a safety hazard, if you are able, wait until the dormant season for these activities. (However, the importance of addressing safety hazards of course outweighs attempts to reduce attracting additional bark beetles.) Check the lower 6 feet, particularly the lower 18 inches, of the trunk for 1.6 inch in diameter pitch tubes or small entrance holes from the adults. Reddish-brown boring dust may be found near the base of the tree as well.

- Fall Home-Invading Insects: Various insects, such as ladybugs, boxelder bugs, seedbugs, and stink bugs (including the invasive brown marmorated stink bug; see entry above) will begin to seek overwintering shelters in warm places, such as homes, throughout the next couple of months. While such invaders do not cause any measurable structural damage, they can become a nuisance especially when they are present in large numbers. While the invasion has not yet begun, if you are not willing to share your home with such insects, now should be the time to repair torn window screens, repair gaps around windows and doors, and shore up any other gaps through which they might enter the home.

Fall Webworm: Hyphantria cunea is native to North America and Mexico. It is now considered a world-wide pest, as it has spread throughout much of Europe and Asia. (For example, it was introduced accidentally into Hungary from North America in the 1940’s.) Hosts include nearly all shade, fruit, and ornamental trees except conifers. In the USA, at least 88 species of trees are hosts for these insects, while in Europe at least 230 species are impacted. In the past history of this pest, it was once thought that the fall webworm was a two-species complex. It is now thought that H. cunea has two color morphs – one black headed and one red headed. These two color forms differ not only in the coloration of the caterpillars and the adults, but also in their behaviors. Caterpillars may go through at least 11 molts, each stage occurring within a silken web they produce over the host. When alarmed, all caterpillars in the group will move in unison in jerking motions that may be a mechanism for self-defense. Depending upon the location and climate, 1-4 generations of fall webworm can occur per year. Fall webworm adult moths lay eggs on the underside of the leaves of host plants in the spring. These eggs hatch in late June or early July depending on climate. Young larvae feed together in groups on the undersides of leaves, first skeletonizing the leaf and then enveloping other leaves and eventually entire branches within their webs. Tiny, early instar (black-headed) fall webworm caterpillars were observed feeding on birch in Hampshire County, MA on 7/5/2022. At this size, caterpillars skeletonize the leaves as they feed. Webs are typically found on the terminal ends of branches. All caterpillar activity occurs within this tent, which becomes filled with leaf fragments, cast skins, and frass. Fully grown larvae then wander from the webs and pupate in protected areas such as the leaf litter where they will remain for the winter. Adult fall webworm moths emerge the following spring/early summer to start the cycle over again. 50+ species of parasites and 36+ species of predators are known to attack fall webworm in North America. Fall webworms typically do not cause extensive damage to their hosts. Nests may be an aesthetic issue for some. If in reach, small fall webworm webs may be pruned out of trees and shrubs and destroyed. Do not set fire to H. cunea webs when they are still attached to the host plant.

Fall Webworm: Hyphantria cunea is native to North America and Mexico. It is now considered a world-wide pest, as it has spread throughout much of Europe and Asia. (For example, it was introduced accidentally into Hungary from North America in the 1940’s.) Hosts include nearly all shade, fruit, and ornamental trees except conifers. In the USA, at least 88 species of trees are hosts for these insects, while in Europe at least 230 species are impacted. In the past history of this pest, it was once thought that the fall webworm was a two-species complex. It is now thought that H. cunea has two color morphs – one black headed and one red headed. These two color forms differ not only in the coloration of the caterpillars and the adults, but also in their behaviors. Caterpillars may go through at least 11 molts, each stage occurring within a silken web they produce over the host. When alarmed, all caterpillars in the group will move in unison in jerking motions that may be a mechanism for self-defense. Depending upon the location and climate, 1-4 generations of fall webworm can occur per year. Fall webworm adult moths lay eggs on the underside of the leaves of host plants in the spring. These eggs hatch in late June or early July depending on climate. Young larvae feed together in groups on the undersides of leaves, first skeletonizing the leaf and then enveloping other leaves and eventually entire branches within their webs. Tiny, early instar (black-headed) fall webworm caterpillars were observed feeding on birch in Hampshire County, MA on 7/5/2022. At this size, caterpillars skeletonize the leaves as they feed. Webs are typically found on the terminal ends of branches. All caterpillar activity occurs within this tent, which becomes filled with leaf fragments, cast skins, and frass. Fully grown larvae then wander from the webs and pupate in protected areas such as the leaf litter where they will remain for the winter. Adult fall webworm moths emerge the following spring/early summer to start the cycle over again. 50+ species of parasites and 36+ species of predators are known to attack fall webworm in North America. Fall webworms typically do not cause extensive damage to their hosts. Nests may be an aesthetic issue for some. If in reach, small fall webworm webs may be pruned out of trees and shrubs and destroyed. Do not set fire to H. cunea webs when they are still attached to the host plant.-

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid: Adelges tsugae is present on eastern and Carolina hemlock. The overwintering hemlock woolly adelgid generation (sistens) is present through mid-spring and produces the spring generation (progrediens) which will be present from early spring through mid-summer. HWA, unlike many other insects, does most of its feeding over the winter. Eggs may be found in wooly masses at the base of hemlock needles beginning in mid-March. Each wooly mass is created by a female who may then lay 50-300 eggs. Eggs hatch and crawlers may be found from mid-March through mid-July. Infested trees may be treated with foliar sprays in late April to early May, using Japanese quince as a phenological indicator. Systemic* applications may be made in the spring and fall, or when soil conditions are favorable for translocation to foliage. Nitrogen fertilizer applications may make hemlock woolly adelgid infestations worse.

*UMass Extension has recently received questions about systemic active ingredient options that may be used to manage hemlock woolly adelgid as an alternative to neonicotinoid insecticides. A couple of options include but are not limited to: abamectin (avermectin/milbemycin), acephate (organophosphate), and azadirachtin (unknown/uncertain mode of action). General use products are available, and each of these active ingredients are labeled for use on trees and/or shrubs. Many products are labeled for use against hemlock woolly adelgid or adelgids.

Of these active ingredients, azadirachtin is considered to be reduced risk. It is generally considered a safe option for honeybees and other beneficial insects, however some products state that azadirachtin is toxic to fish and other aquatic invertebrates (and as such, the products come with special instructions for precautions when using them near water).

Unlike the neonicotinoids (dinotefuran and imidacloprid, primarily), these systemic active ingredient alternatives do not have efficacy data for the management of hemlock woolly adelgid readily available in the scientific literature. Further research concerning abamectin, acephate, and azadiractin (as well as chlorantraniliprole, a ryanodine receptor modulator/diamide/anthranilic diamide) and their efficacy against hemlock woolly adelgid is needed (McCarty and Addesso, 2019).

Additionally, do not forget that during drought conditions, systemic applications may prove difficult. It is important to follow proper watering practices for high value trees and shrubs in the landscape (while observing local watering restrictions). Watering after systemic applications may improve tree uptake. Follow all label instructions for safety and proper use.

-

Hickory Tussock Moth: Lophocampa caryae is native to southern Canada and the northeastern United States. There is one generation per year. Overwintering occurs as a pupa inside a fuzzy, oval shaped cocoon. Adult moths emerge approximately in May and their presence can continue into July. Females will lay clusters of 100+ eggs together on the underside of leaves. Females of this species can fly, however they have been called weak fliers due to their large size. When first hatched from their eggs, the young caterpillars will feed gregariously in a group, eventually dispersing and heading out on their own to forage. Caterpillar maturity can take up to three months and color changes occur during this time. These caterpillars are essentially white with some black markings and a black head capsule. They are very hairy, and should not be handled with bare hands as many people can have skin irritation or rashes (dermatitis) as a result of interacting with hickory tussock moth hairs. By late September, the caterpillars will create their oval, fuzzy cocoons hidden in the leaf litter where they will again overwinter. Hosts whose leaves are fed upon by these caterpillars include but are not limited to hickory, walnut, butternut, linden, apple, basswood, birch, elm, black locust, and aspen. Maple and oak have also been reportedly fed upon by this insect. Several wasp species are parasitoids of hickory tussock moth caterpillars.

- Lacebugs: Stephanitis spp. lacebugs such as S. pyriodes can cause severe injury to azalea foliage. S. rhododendri can be common on rhododendron and mountain laurel. S. takeyai has been found developing on Japanese andromeda, leucothoe, styrax, and willow. Stephanitis spp. lace bug activity should be monitored through September. Before populations become too large, treat with a summer rate horticultural oil spray as needed. Be sure to target the undersides of the foliage in order to get proper coverage of the insects. Certain azalea and andromeda cultivars may be less preferred by lace bugs.

Redheaded Pine Sawfly: Neodiprion lecontei can be an important native pest of ornamental, forest, and plantation pines. Jack, shortleaf, loblolly, slash, red, and other two- and three-needle pines are suitable hosts, and occasionally others in proximity to these. This insect overwinters as a prepupa in a cocoon in the leaf litter near its hosts. Pupation occurs in the spring and adults emerge a few weeks later. Some prepupae have delayed emergence, which can occur 2 or 3 years later. Females lay over 100 eggs in rows of slits in the edges of several needles. Egg laying can take place without mating, with unfertilized eggs producing males. Fertilized eggs produce males and females. Larvae hatch in a month and feed gregariously. Eventually, they drop to the ground to spin the overwintering cocoons. Historically in New England, a single generation occurred per year. In more southern parts of its range, 2-3 generations may occur annually. Anecdotally, as the growing season and winters warm in New England due to climate change, it seems a second generation of this insect is possible and may already be occurring. Natural enemies include rodent predators of the pupae, as well as diseases of the larvae. Larvae were found defoliating Pinus x densithunbergii ‘Jane Kluis’ in Florence, MA on 9/10/2022 (Photos courtesy of Daniel Lyons).

Redheaded Pine Sawfly: Neodiprion lecontei can be an important native pest of ornamental, forest, and plantation pines. Jack, shortleaf, loblolly, slash, red, and other two- and three-needle pines are suitable hosts, and occasionally others in proximity to these. This insect overwinters as a prepupa in a cocoon in the leaf litter near its hosts. Pupation occurs in the spring and adults emerge a few weeks later. Some prepupae have delayed emergence, which can occur 2 or 3 years later. Females lay over 100 eggs in rows of slits in the edges of several needles. Egg laying can take place without mating, with unfertilized eggs producing males. Fertilized eggs produce males and females. Larvae hatch in a month and feed gregariously. Eventually, they drop to the ground to spin the overwintering cocoons. Historically in New England, a single generation occurred per year. In more southern parts of its range, 2-3 generations may occur annually. Anecdotally, as the growing season and winters warm in New England due to climate change, it seems a second generation of this insect is possible and may already be occurring. Natural enemies include rodent predators of the pupae, as well as diseases of the larvae. Larvae were found defoliating Pinus x densithunbergii ‘Jane Kluis’ in Florence, MA on 9/10/2022 (Photos courtesy of Daniel Lyons).-

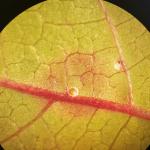

Sweetgum Scale: Diaspidiotus liquidambaris is a native armored scale insect known from much of North America. It has been observed in CT, DC, DE, FL, GA, IL, IN, LA, MD, MO, MS, NC, NJ, NY, OH, PA, SC, TN, and VA (Miller and Davidson, 2005). This species has a limited host range, favoring sweetgum (Liquidambar) and has been examined on magnolia (Magnolia). Historically, it has also been reported on Acer. Adult female covers are circular, white or gray, with a yellow center and a thin white margin of wax. Male covers are oval, white and yellow. Scales may be found on stems and leaves. Small gall-like depressions are formed on leaf undersides where scales are feeding. Magnification is required to observe the scales themselves. Female and male scales as well as the gall-like formations they cause on the upper surface of sweetgum leaves are shown in these photographs of samples from South Hadley, MA collected on 9/19/2022 and submitted to the UMass Plant Diagnostics Laboratory (Photos: Tawny Simisky).

Sweetgum Scale: Diaspidiotus liquidambaris is a native armored scale insect known from much of North America. It has been observed in CT, DC, DE, FL, GA, IL, IN, LA, MD, MO, MS, NC, NJ, NY, OH, PA, SC, TN, and VA (Miller and Davidson, 2005). This species has a limited host range, favoring sweetgum (Liquidambar) and has been examined on magnolia (Magnolia). Historically, it has also been reported on Acer. Adult female covers are circular, white or gray, with a yellow center and a thin white margin of wax. Male covers are oval, white and yellow. Scales may be found on stems and leaves. Small gall-like depressions are formed on leaf undersides where scales are feeding. Magnification is required to observe the scales themselves. Female and male scales as well as the gall-like formations they cause on the upper surface of sweetgum leaves are shown in these photographs of samples from South Hadley, MA collected on 9/19/2022 and submitted to the UMass Plant Diagnostics Laboratory (Photos: Tawny Simisky).

The sweetgum scale is known to have two generations per year in Maryland. The exact timing of the life cycle in Massachusetts may not be entirely understood. Fertilized adult females overwinter on host plant bark in Maryland. Eggs and crawlers (mobile immature life stage) are present from mid-May through June. Many of these crawlers will settle on host plant leaves. Adults are present by mid-June. A second generation of crawlers may be possible from early July to early October. Most of the second generation crawlers are thought to settle on the host plant bark. Second generation adults may appear in early September. Adult males are winged in the first generation and wingless in the second. In Ohio, unmated adult females and pupal males at the base of twig buds overwinter and crawlers appear in early June - so life cycle differences exist depending upon location.

This insect produces galls on the upper leaf surfaces of its host that can be unsightly to some. Historically, this scale has been reported to have economic impacts on its host in Florida and may be a pest of nurseries in Missouri. Miller and Davidson (2005) rate the sweetgum scale as an occasional pest. In low populations, this insect is a minor pest. If populations become high, leaf yellowing and drop can occur. However, management may not be necessary.

-

Tuliptree Aphid: Illinoia liriodendri is a species of aphid associated with the tuliptree, wherever it is grown. Depending upon local temperatures, these aphids may be present from mid-June through early fall. Large populations can develop by late summer. Some leaves, especially those in the outer canopy, may turn brown or yellow and drop from infested trees prematurely. The most significant impact these aphids can have is typically the resulting honeydew, or sugary excrement, which may be present in excessive amounts and coat leaves and branches, leading to sooty mold growth. This honeydew may also make a mess of anything beneath the tree. Wingless adults are approximately 1/8 inch in length, oval, and can range in color from pale green to yellow. There are several generations per year. This is a native insect. Management is typically not necessary, as this insect does not significantly impact the overall health of its host. Tuliptree aphids also have plenty of natural enemies, such as ladybeetles and parasites.

-