A monthly e-newsletter from UMass Extension for landscapers, arborists, and other Green Industry professionals, including monthly tips for home gardeners.

To read individual sections of the message, click on the section headings below to expand the content:

Hot Topics

Garden Calendar Photo Contest!

There's still time to submit photos to our annual photo context for use in the next UMass Garden Calendar - the deadline is April 1st! UMass Extension accepts photos from the public for possible use in the annual UMass Garden Calendar. Photos must be horizontally oriented with high resolution. Submissions will be judged by the calendar team at UMass Extension and may earn a spot in a future Garden Calendar. Winning photographers will be credited in the Garden Calendar and will receive 5 free calendars.

For more details, go to: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/publications-resources/garden-calendar/garden-calendar-photo-contest.

Looking for More Information about Beech Leaf Disease?

The US Forest Service has organized an online workshop concerning beech leaf disease for April 15, 2021. There will be over a dozen presentations on topics including how to recognize symptoms, updates from state surveys and monitoring, research efforts, and preliminary information about management. SAF and ISA credits will be available.

For more information and to register, visit the USDA Forest Service's Event Info and Registration Page. Questions? Contact Cameron McIntire at cameron.mcintire@usda.gov or Danielle Martin at danielle.k.martin@usda.gov.

Be on the Lookout for the Spotted Lanternfly!

The Problem

The spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula) is an invasive, non-native Hemipteran (true bugs, cicadas, hoppers, aphids, etc.) in the family Fulgoridae (the planthoppers). This insect uses piercing-sucking mouthparts to remove plant fluids from over 103 different host plants (Barringer and Ciafré, 2020), including tree of heaven (TOH; Ailanthus altissima), apple (Malus spp.), plum, cherry, peach, apricot (Prunus spp.), grape (Vitis spp.), American beech (Fagus grandifolia), American linden (Tilia americana), American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis), big-toothed aspen (Populus grandidentata), black birch (Betula lenta), black cherry (Prunus serotina), black gum (Nyssa sylvatica), black walnut (Juglans nigra), dogwood (Cornus spp.), Japanese snowbell (Styrax japonicus), maple (Acer spp.), oak (Quercus spp.), paper birch (Betula papyrifera), pignut hickory (Carya glabra), sassafras (Sassafras albidum), serviceberry (Amelanchier canadensis), slippery elm (Ulmus rubra), tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera), white ash (Fraxinus americana), willow (Salix spp.), and many others.

While tree of heaven is considered a preferred host, spotted lanternfly will feed on other susceptible hosts and lay its eggs on just about any flat surface. Because of this, it is very easy to accidentally move spotted lanternfly egg masses, in addition to adults and nymphs (immatures).

The Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources reports that single, dead individual spotted lanternflies have been detected in Middlesex, Norfolk, and Worcester Counties, and that in each case, SLF that were detected were traced back to infested areas in Pennsylvania. Spotted lanternfly is not currently thought to be established and reproducing in Massachusetts. However, we need to remain vigilant because it is clear that this insect is an excellent hitchhiker and capable of moving great distances with our accidental help.

Spotted lanternfly feeding has caused mortality (perhaps in addition to abiotic factors) and losses of grape crops in Pennsylvania. Additionally, flagging and branch dieback has been observed in that state on some host trees. However the long-term impacts of spotted lanternfly feeding are not yet completely understood on all susceptible hosts. That said, this invasive insect has become a significant nuisance in the areas of the US where it has become established. Spotted lanternfly adults and nymphs produce a sugary, liquid excrement known as honeydew, which can coat leaves, plants, and other objects (such as outdoor furniture, cars, etc.) that are found beneath infested host plants. This honeydew can promote the growth of black sooty mold and also attract stinging insects, such as wasps. Adults can gather in very large numbers in managed landscapes. In summary, we do not want the spotted lanternfly to become established in Massachusetts!

Timing and Identification of Life Stages

Eggs: Overwinter and are laid starting in September and hatch in May in Pennsylvania. Freshly laid egg masses appear as if coated with a white substance. As they age, the egg masses look as if they are coated with gray mud, which eventually takes on a dry/cracked appearance. Very old egg masses may look like rows of 30-50 brown seed-like structures aligned vertically in columns.

Eggs: Overwinter and are laid starting in September and hatch in May in Pennsylvania. Freshly laid egg masses appear as if coated with a white substance. As they age, the egg masses look as if they are coated with gray mud, which eventually takes on a dry/cracked appearance. Very old egg masses may look like rows of 30-50 brown seed-like structures aligned vertically in columns.

Nymphs:

Nymphs:

1st – 3rd Instars: Present following egg hatch from May through roughly June in PA. Early instars (immature stages; 1st, 2nd, and 3rd instar) are black with white spots.

4th Instar: Present in July in PA. SLF develop red patches in addition to the black color with white spots. This is the last immature stage before they mature into an adult.

Adults: Present from July until frost kills them, usually in November and December in PA. Adults are 1 inch long and ½ inch wide at rest. The forewing is gray with black spots of varying sizes and the wing tips have black spots outlined in gray. Hind wings have contrasting patches of red and black with a white band. The legs and head are black, and the abdomen is yellow with black bands.

How You Can Help!

Keep your eyes open! Be on the lookout for any of the aforementioned life stages of this insect in Massachusetts and report anything suspicious immediately to the MA Department of Agricultural Resources (MDAR) at: https://massnrc.org/pests/slfreport.aspx

MDAR has recently released some Best Management Practices for Nurseries and Landscapers, which can be found at: https://massnrc.org/pests/linkeddocuments/MANurseryBMPs.pdf

- These BMP’s include tips for inspecting materials that may be likely to accidentally transport spotted lanternfly, including but not limited to: vehicles, trailers, shipping/storage containers, bulk/crushed stone, pallets, firewood, hand trucks and landscaping supplies, lawn furniture/decorations, nursery stock and potted plants, storage sheds and other outdoor structures, trash cans, wheel barrows, and virtually any flat surface. It is recommended that nursery owners and operators, landscapers, garden centers, and property owners in Massachusetts inspect these items and report anything suspicious.

MDAR has also released some Best Management Practices for Moving Companies and the Moving Industry, which can be found at: https://massnrc.org/pests/linkeddocuments/SLFChecklistMovingIndustryMA.pdf

- These BMP’s include a checklist for inspecting further materials that might accidentally transport this insect, as well as an excellent photo guide depicting some of the interesting items spotted lanternflies may lay their egg masses on!

For more information about spotted lanternfly, visit:

- UMass Extension’s Fact Sheet: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/spotted-lanternfly

- MDAR’s Massachusetts Introduced Pests Outreach Blog: https://massnrc.org/pests/blog/

- MDAR’s Spotted Lanternfly Mini Poster: https://massnrc.org/pests/linkeddocuments/SLFminiposter.pdf

- Order Spotted Lanternfly Materials from MDAR: http://bit.ly/FPOMOrder

- MDAR's Spotted Lanternfly Fact Sheet: https://massnrc.org/pests/pestFAQsheets/spottedlanternfly.html

- A Map of Known SLF Infestations in the US: https://nysipm.cornell.edu/environment/invasive-species-exotic-pests/spotted-lanternfly/

Tawny Simisky, Extension Entomologist, UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, & Urban Forestry Program

Featured Plant

Hamamelis x intermedia, Witchhazel ‘Arnold Promise’

Hamamelis x intermedia is a hybrid between Hamamelis mollis (Chinese witchhazel) and Hamamelis japonica (Japanese witchhazel). It is an upright or wide spreading, multi-stemmed small tree or large shrub. There are several attractive cultivars of Hamamelis x intermedia with variable habits ranging from broad spreading to upright vase shaped.

This witchhazel adds late winter to early spring interest to the landscape with clusters of fragrant flowers that open in February to March and may persist up to a month. Flowers have interesting, crinkled, ribbon-like strap shaped flowers that can range in color from yellow to orange to copper red or bronzed red, depending on the cultivar. They are able to resist harsh winter weather, providing colorful flowers when other landscape interest in sparse. Leaves are alternate, broad-oval, serrate, 2 to 6 inches long and dark green to blue-green in color. In fall, leaves turn yellow to orange to copper red or bronzy read, also depending on the cultivar.

Hamamelis x intermedia is hardy in USDA zones 5 to 8. They perform best in organically rich, moist, well drained soils in full sun to part shade. They have very slow growth in hot, dry, exposed locations. Maximum flowering is achieved in full sun but they can produce reliably acceptable bloom in part shade. A green background can help to enhance the flower display. Witchhazel can be used as a specimen plant or in small groups in the shrub border. It should be planted where the winter blooms can be appreciated.

Potential problems include caterpillars, Japanese beetles, leaf gall aphids, weevils, scale, leafroller and leaf miner, which are potential occasional insect pests. Potential diseases include powdery mildew, occasional leaf spots and rots. Leaf scorch may occur during periods of summer drought.

‘Arnold Promise’ is one of the oldest cultivars and is the most popular. It is an upright, vase shaped cultivar with ascending branches and a spreading habit. It grows 15 to 20 feet tall with broad oval green leaves. Clusters of bright yellow flowers each with four narrow ribbon-like slightly twisted petals and a reddish calyx cup appear in February to March. Fall color is an attractive rich yellow to orange.

Other cultivars include:

- ‘Diane’ - Medium spreading habit. Flowers are copper red in color with mild fragrance. Fall color is red yellow and orange. Old leaves may persist and require removal to maximize flower effect.

- ‘Jelena’ - Sstrong horizontal habit. Flowers are copper red and fragrant. Fall color is orange red.

- ‘Pallida’ - Smaller than ‘Arnold Promise’ and better suited for small gardens. Flowers are soft yellow in color and highly fragrant. Leaves turn yellow to yellow-orange in fall.

- ‘Ruby Glow’ - Flowers are deep coppery-red to bronzy-red. Leaves turn to orange red in fall.

- ‘Orange Beauty’ - Mildly fragrant, deep yellow to orange-yellow flowers. Leaves turn yellow, orange and red in fall

Geoffrey Njue, UMass Extension Sustainable Landscapes Specialist

Questions & Answers

Q. Last November, when I was harvesting my leeks, I noticed numerous small reddish-brown insect casings all over the plants. The limp plants looked like they had tracks running through the leaves and soon began to rot; not a single one was salvageable. What is going on? Is there anything I can do this year to prevent the problem?

A. What you most likely saw were pupae of the allium leafminer, a relatively new pest in Northeastern vegetable gardens. It is a fly whose larvae cause damage on plants in the Allium genus: leeks, garlic, onions, shallots, chives, scallions. Some wild and ornamental alliums are also vulnerable. The fly larvae feed on and tunnel through leaves of these plants, leaving injured areas open to infection by bacteria and fungi. Not only are the results unsightly, but they can also cause crop spoilage, as you found out with your leeks.

Allium leafminer is native to Europe, where commercial growers have adopted spray programs to combat the pest. It was first noted in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in late 2015 but has since spread outside the state to locations in New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maryland and New Jersey.

Adults are emerging and active any time between late March and May. Allium leafminer flies are fairly small and indistinct; much more distinct are the lines of holes poked by the flies in the upper portions of leaves to feed and to lay their eggs. Hatched larvae then “mine” their way through the leaves, leaving characteristic tunnels as they feed their way down the plant. While the feeding/egg laying holes and softened mined tissue can cause distorted leaves, they also provide entry points and distribution pathways for bacterial and fungal infections. Larvae form reddish brown pupae at the base of plants, which remain dormant until a second generation of adult flies emerges in September and October. The egg-laying, larval-tunneling processes repeat themselves and the resultant pupae overwinter in plant residue or in the ground until the following spring.

According to research at Cornell and Penn State, crops with available top growth during either spring or fall when adults are active are most prone to infestation, which means that it’s no surprise that your leafy green leeks were an easy target last fall. In the spring, you might look for activity on garlic, onions, scallions, and chives.

Employ a variety of the following means to address the issue this coming growing season:

- Practice crop rotation. Keep any allium crops out of the same area for the next few years if possible.

- Use yellow sticky cards to monitor for the presence of pests. University Extension sites usually have excellent images that can help with pest identification, including allium leafminer. Become familiar with what the leafminer’s different life stages look like.

- Protect allium crops with row covers during the times when adult leafminers are active. Row covers provide a physical barrier to egg-laying.

- Delay spring planting allium seedlings a few weeks to avoid the first generation of adults.

- Use an insecticide, such as one containing spinosad, a naturally occurring bacterial fermentation product. Researchers at Cornell have reported success with a variety of insecticides (see Resources below). Be sure to read and follow all label recommendations.

Resources:

Beissinger, A. 2020. Allium leafminer in Connecticut. University of Connecticut Plant Diagnostic Laboratory. https://plant.lab.uconn.edu/2020/05/01/allium-leafminer-in-connecticut/#

Hutchinson, M. Allium leaf miner. Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture. https://www.agriculture.pa.gov/Plants_Land_Water/PlantIndustry/Entomology/Pages/ALLIUM-LEAFMINER.aspx

Nault, B. A., Iglesias, L. E., Harding, R. S., Grundberg, E. A., Rusinek, T., Elkner, T. E., Lingbeek, B. J., & Fleischer, S. J. (2020). Managing Allium Leafminer (Diptera: Agromyzidae): An Emerging Pest of Allium Crops in North America. Journal of economic entomology, 113(5), 2300-2309. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toaa128

Jennifer Kujawski, Horticulturist

Trouble Maker of the Month

Winter Injury for Conifers and Broad-Leaved Evergreens

Conifers and broad-leaved evergreens in the landscape can suffer from various forms of winter-related injury. Typically, symptoms of the damage become apparent in late winter to early spring as temperatures warm and plants deacclimate. The ways in which conifers and evergreens are injured include:

- Exposure to extreme cold temperatures and harsh winds.

- Loss of winter hardiness from a mid- to late winter thaw.

- Transpirational water loss during warm winter days.

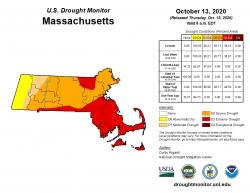

Exposure injury often occurs when temperatures are unseasonably cold and accompanied by strong winds. These conditions create wind chill values that are well below zero, sometimes ranging between -20 to -30°F. Plants that suffer damage may be marginally hardy in our region, recently transplanted and suffering shock, or reside in settings with no protection from other plants, structures or environmental features. In other cases, even mature, well-established trees and shrubs suffer from exposure injury as a result of harsh winter weather. In these cases, trees or shrubs may have been predisposed by drought, insect infestation or disease, which has inhibited their ability to normally acclimate for the winter. The drought conditions during the 2020 growing season may result in increased cases of exposure injury for some plants. Symptoms of exposure injury on landscape conifers and evergreens can vary from discolored needles (pale green to yellow to brown), marginal leaf browning, premature needle/leaf shedding and a total collapse of affected branches. Plants that may suffer from this type of winter injury include rhododendron/ azalea (Rhododendron), Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria), and true cedar (Cedrus).

Symptoms resulting from loss of cold hardiness due to a winter thaw can develop anytime from mid-winter to early spring. Prolonged periods of unseasonably warm temperatures followed by a rapid return to cold weather can burn young and exposed tissues. Chlorotic or mottled foliage, often with a desiccated appearance, are symptoms of this damage. While temperatures were above-average in December 2020 and January 2021, the region never experienced the type of thaw (i.e. several consecutive days with temperatures >50°F) that could result in widespread thawing and deacclimation for woody plants. Thus, this type of winter injury is unlikely to appear this spring season.

Finally, winter burn can develop as a result of transpirational water loss during the winter months. Sections of the tree or shrub canopy facing the sun are warmed during bright, sunny winter days, especially when reflective snow cover is present. The warming induces transpiration (water evaporation from the stomata to reduce heat) from the needles or leaves. However, since the soil and roots are frozen, water that is transpired from the needles cannot be replaced, leading to drying and desiccation. Because a consistent snowpack has been present this winter, the reflective snow element has been widespread throughout the region. Trees and shrubs likely to suffer from this type of winter injury include large rhododendrons (Rhododendron) and hemlock (Tsuga). The leaf curling that rhododendrons exhibit during the winter months helps to reduce the leaf area, limiting heat loading and transpiration demands.

Unfortunately, little can be done to remedy plant parts injured during the winter months. Pruning and removal of badly damaged shoots and branches may be required, to limit the colonization and establishment of opportunistic foliar pathogens. This is especially true for rhododendron and holly (Ilex), as the fungal pathogens Pestalotiopsis and Phyllosticta can cause additional leaf dieback when plants are predisposed by winter burn. Extra care and attention may be required during the growing season for plants injured during the winter, such as supplemental watering and fertilization.

Nicholas J. Brazee, UMass Extenstion Plant Pathologist

Garden Clippings Tips of the Month

March is the time to:

-

Be prepared for winter injury. Winter injury is often seen on broadleaved, needled, and scale-like foliage of evergreen trees and shrubs. The drought conditions of summer and fall 2020 are likely

to result in increased winter injury. Evergreen plants with damaged root systems, in areas lacking soil moisture, or in exposed areas are more susceptible to winter damage. Winter injury is often seen as browning of needles or as marginal browning on broadleaved evergreens; damage is typically most severe on the south or southwest facing portions of the plant. It can vary from slight foliar damage to complete browning and death of a plant. Although winter injury may have already become visible, it may not be apparent until well into the growing season. Foliage and woody tissues damaged by winter injury should be removed as soon as the extent of damage is able to be evaluated, typically around the time new growth begins. Tissue with winter injury are typically more susceptible to fungal pathogens and often a site for disease to get established in an otherwise healthy plant.

to result in increased winter injury. Evergreen plants with damaged root systems, in areas lacking soil moisture, or in exposed areas are more susceptible to winter damage. Winter injury is often seen as browning of needles or as marginal browning on broadleaved evergreens; damage is typically most severe on the south or southwest facing portions of the plant. It can vary from slight foliar damage to complete browning and death of a plant. Although winter injury may have already become visible, it may not be apparent until well into the growing season. Foliage and woody tissues damaged by winter injury should be removed as soon as the extent of damage is able to be evaluated, typically around the time new growth begins. Tissue with winter injury are typically more susceptible to fungal pathogens and often a site for disease to get established in an otherwise healthy plant. -

Consider some pruning. Late winter and early spring, before growth resumes, is an ideal time for structural pruning. The lack of foliage allows the pruner to observe the structure of a tree or shrub and make structural pruning cuts. Remember the ideal structure for most (not all) trees is a central leader with a system of scaffold branches that are larger in the lower portion of the tree and get progressively smaller toward the top. Pruning at this time is also ideal for identifying and removing competing leaders in the upper portion of a tree. When pruning shrubs, especially those that produce new shoots from the base like blueberry, elderberry, spirea, viburnum and winterberry, start by removing one or two of the oldest stems. This will help keep the shrubs healthy and promote the emergence of young vigorous growth from the base of the plant.

-

Be aware of soil compaction. Late winter and early spring are times when soils are often saturated and therefore susceptible to soil compaction. Compaction destroys soil properties and may result in poor drainage, poor water infiltration, impediment of root growth and may cause anaerobic conditions. Compaction is difficult to fix, so avoidance is the best option. When possible, utilize sheets of plywood to help distribute weight when moving heavy materials or equipment over wet soils. It only takes one pass of heavy equipment to compact wet soils.

-

Have supplies ready for starting seeds, including soilless media, pots, and lights. A good seed starting mix should be sterilized, contain little or no fertilizer charge, and should be of a fine consistency; this is typically a mixture of fine peat and vermiculite. Use small containers to start seeds and transplant into larger containers as the plants grow. When reusing containers, wash to remove debris and soil and then sterilize by soaking in 10% bleach (bleach once diluted is only effective for about a day). Choose LED’s that emit light primarily in the blue spectrum for growing seedlings; “grow bulbs” or “cool white” are the best options for fluorescent bulbs.

-

Start some cool season vegetable transplants like brassicas; cabbage, broccoli, and cauliflower. Germinate the seeds under warm conditions but grow the plants at cooler temperatures, 55-65oF if possible. Early March is still suitable for starting onions from seed and other cool season crops like swiss chard. By the end of March, you may want to start thinking about starting slower warm season transplants like peppers.

-

Get your tools ready. Now is a great time to prep and fix tools instead of losing valuable time when conditions are favorable for working outdoors. Replace broken handles and apply sports wrap to handles that have splinters. Sharpen shovels and hoes. Make sure tires of wheelbarrows and other equipment still hold air.

-

Beware of ticks! Black-legged tick (deer tick) adults will be active any time the temperatures are above freezing. Keep yourself protected by wearing permethrin treated clothing and doing vigilant tick checks when done working outside for the day.

Russ Norton, Agriculture & Horticulture Extension Educator, Cape Cod Cooperative Extension

Do Honey Bees Transmit Diseases to Native Bees on Flowers?

Just as pathogens like COVID-19 harm human health, there are numerous bacteria, viruses and parasites that sicken bees. Some bee pathogens affect only a single species (e.g. Varroa mites, which only parasitize honey bees), but others can infect many different types of bees. There are hundreds of bee species that are native to New England, most of whom live a solitary lifestyle. Researchers are beginning to wonder whether non-native managed honey bees – who live in crowded colonies and are therefore especially vulnerable to pathogens – could infect their wild bee neighbors.

Just as pathogens like COVID-19 harm human health, there are numerous bacteria, viruses and parasites that sicken bees. Some bee pathogens affect only a single species (e.g. Varroa mites, which only parasitize honey bees), but others can infect many different types of bees. There are hundreds of bee species that are native to New England, most of whom live a solitary lifestyle. Researchers are beginning to wonder whether non-native managed honey bees – who live in crowded colonies and are therefore especially vulnerable to pathogens – could infect their wild bee neighbors.

Researchers at the University of Vermont recently tested whether virus transmission can occur on flowers when honey bees leave behind contaminated feces or glandular secretions. In experimental tents, they let virus-laden honey bees forage on a patch of flowers, and then allowed virus-free bumblebees to forage on those same flowers. They later tested the flowers and the bumble bees for viruses. They found that honey bees indeed deposited viruses on flowers. However, the viruses were not transmitted from the flowers to the bumblebees. The authors caution that the viruses may have been transmitted in levels too low to be detected, and that transmission may still be happening in the wild.

Why is this research important?

Honey bees provide critical pollination services for crops and they produce honey that we enjoy. However, it is important to remember that they are not native to North America and may have unintended effects on native flora and fauna. Researchers have recently begun to wonder whether there is disease spillover from honey bee colonies to nearby native bees. This is the first paper to show that honey bees can indeed deposit viruses on flowers. It is an important step in understanding the impact that honey bees have on native ecosystems. Read the full study at https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/authors?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0221800.

A New Honey Bee Textbook for Veterinarians (and Beekeepers)

A new veterinary textbook on honey bee heath was published this winter: Honey Bee Medicine for the Veterinary Practitioner. It is the most comprehensive textbook on honey bee veterinary medicine for US practitioners published in recent years, and features rock-star authors including Tom Seeley, Randy Oliver, David Tarpy, Meghan Milbrath, Dewey Caron, Margarita López-Uribe, Jay Evans and many more. It is also exciting because it complements national and local efforts (like the Honey Bee Veterinary Consortium and the MA Bee-Vet Project) to train veterinarians to diagnose and treat honey bee diseases.

A new veterinary textbook on honey bee heath was published this winter: Honey Bee Medicine for the Veterinary Practitioner. It is the most comprehensive textbook on honey bee veterinary medicine for US practitioners published in recent years, and features rock-star authors including Tom Seeley, Randy Oliver, David Tarpy, Meghan Milbrath, Dewey Caron, Margarita López-Uribe, Jay Evans and many more. It is also exciting because it complements national and local efforts (like the Honey Bee Veterinary Consortium and the MA Bee-Vet Project) to train veterinarians to diagnose and treat honey bee diseases.

- Learn more about the Honey Bee Veterinary Consortium at https://www.hbvc.org/.

- Learn more about the MA Bee-Vet Project at https://ag.umass.edu/resources/pollinators/honey-bees/education/ma-bee-veterinarian-project.

For more info on new bee research, check out “The Research Buzz” – a quarterly column summarizing the latest in pollinator research. It is published in the Massachusetts Beekeeping Association newsletter, and also on the UMass Extension website. You can find it here.

Hannah Whitehead, UMass Extension Honey Bee Educator

Upcoming Events

For more details for any of these events, go to the UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, and Urban Forestry Program Upcoming Events Page.

-

Mar 13 - Mass Aggie Seminars: Backyard Brambles - a Virtual Workshop

For the full schedule and more details, go to: https://ag.umass.edu/fruit/news-events/mass-aggie-seminars-2021 -

Mar 22 - Developing an Invasive Plant Management Program (part 4 of our Invasive Plant Management Certification series)

Credits: 4 pesticide contact hours available in categories 29, 36, 37, 40, 48, and Applicator’s License. Association credits: 4 ISA, 1 MCH, 2 MCA, and 2 MCLP available. Full details at: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education/invasive-plant-certification-program -

Mar 24 & 25 - Spring Kickoff for Landscapers: UMass Extension's Landscape Education Day

Credits: For EACH DAY, 2 pesticide contact hours available for categories 29, 36, and Applicators License. Association credits: 3 ISA, 1 MCH, 1 MCA, and 1 MCLP available for each day. Full details at: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/events/spring-kickoff-for-landscapers-umass-extensions-landscape-education-day -

Apr 7 - Glyphosate 411 Weedinar

Credits: 3 pesticide contact hours available for all private categories, 33, 36, 37, 39, 40, Dealer, and Applicators License (core) available. Association credits: 2.5 ISA, 1 MCA, 1 MCLP, and 1 MCH available. Full details at: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/events/weedinar-glyphosate-411-0 -

Apr 22 - Ask The Entomologist

Registration limited to 25 participants.

Credits: 1 pesticide contact hour available for categories 29, 35, 36, 48 and Applicators (core) license. Association credits: 1 ISA, .5 MCA Education Credit, .5 MCLP Education Credit, and 1 MCH credit available. Full details at: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/events/ask-entomologist

Pesticide Exam Preparation and Recertification Courses

These workshops are currently being offered online. Contact Natalia Clifton at nclifton@umass.edu or go to https://www.umass.edu/pested for more info.

InsectXaminer!

Episodes so far featuring gypsy moth, lily leaf beetle, euonymus caterpillar, and imported willow leaf beetle can be found at: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/insectxaminer

TickTalk with TickReport Webinars

To view recordings of past webinars in this series, go to: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/ticktalk-with-tickreport-webinars

Additional Resources

For detailed reports on growing conditions and pest activity – Check out the Landscape Message

For professional turf managers - Check out our Turf Management Updates

For commercial growers of greenhouse crops and flowers - Check out the New England Greenhouse Update website

For home gardeners and garden retailers - Check out our home lawn and garden resources. UMass Extension also has a Twitter feed that provides timely, daily gardening tips, sunrise and sunset times to home gardeners at twitter.com/UMassGardenClip

Diagnostic Services

Landscape and Turf Problem Diagnostics - The UMass Plant Diagnostic Lab is accepting plant disease, insect pest and invasive plant/weed samples (mail-in only - walk-in samples cannot be accepted). The lab serves commercial landscape contractors, turf managers, arborists, nurseries and other green industry professionals. It provides woody plant and turf disease analysis, woody plant and turf insect identification, turfgrass identification, weed identification, and offers a report of pest management strategies that are research based, economically sound and environmentally appropriate for the situation. Accurate diagnosis for a turf or landscape problem can often eliminate or reduce the need for pesticide use. Please refer to our website for instructions on sample submission and to access the submission form at https://ag.umass.edu/services/plant-diagnostics-laboratory. Mail delivery services and staffing have been altered due to the pandemic, so please allow for some additional time for samples to arrive at the lab and undergo the diagnostic process.

Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing - The UMass Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Lab is accepting orders for routine soil analysis and particle size analysis ONLY (please do not send orders for other types of analyses at this time). Send orders via USPS, UPS, FedEx or other private carrier (hand delivered orders cannot be accepted at this time). Processing time may be longer than usual since the lab is operating with reduced staff and staggered shifts. The lab provides test results and recommendations that lead to the wise and economical use of soils and soil amendments. For updates and order forms, visit the UMass Soil and Plant Nutrient Testing Laboratory web site.

Tick Testing - The UMass Laboratory of Medical Zoology is currently unable to accept samples for tick testing at this time. The Massachusetts Department of Public Health provides a list of potential tick identification and testing alternatives at: https://www.mass.gov/service-details/tick-identification-and-testing-services