UMass Extension's Landscape Message is an educational newsletter intended to inform and guide Massachusetts Green Industry professionals in the management of our collective landscape. Detailed reports from scouts and Extension specialists on growing conditions, pest activity, and cultural practices for the management of woody ornamentals, trees, and turf are regular features. The following issue has been updated to provide timely management information and the latest regional news and environmental data.

The Landscape Message will be updated bi-monthly in September. The next message will be posted on September 3. To receive immediate notification when the next Landscape Message update is posted, be sure to join our e-mail list

To read individual sections of the message, click on the section headings below to expand the content:

Scouting Information by Region

Environmental Data

The following data was collected on or about August 18, 2021. Total accumulated growing degree days (GDD) represent the heating units above a 50° F baseline temperature collected via regional NEWA stations for the 2021 calendar year. This information is intended for use as a guide for monitoring the developmental stages of pests in your location and planning management strategies accordingly.

|

MA Region/Location |

GDD |

Soil Temp |

Precipitation |

Time/Date of Readings |

||

|

2-Week Gain |

2021 Total |

Sun |

Shade |

|||

|

CAPE |

344.5 |

1914 |

72 |

68 |

1.27 |

12:00 PM 8/18 |

|

SOUTHEAST |

343.5 |

1970.5 |

82 |

74 |

4.38 |

4:00 PM 8/18 |

|

NORTH SHORE |

346 |

2050 |

72 |

67 |

1.42 |

10:30 AM 8/18 |

|

EAST |

354.5 |

2078 |

72 |

67 |

1.37 |

5:00 PM 8/18 |

|

METRO |

337 |

1951 |

67 |

60 |

1.39 |

6:15 AM 8/18 |

|

CENTRAL |

341 |

2007.5 |

70 |

66 |

0.83 |

8:00 AM 8/18 |

|

PIONEER VALLEY |

344.5 |

2030 |

75 |

69 |

0.59 |

1:00 PM 8/18 |

|

BERKSHIRES |

295 |

1679 |

73 |

67 |

1.47 |

7:00 AM 8/18 |

|

AVERAGE |

338 |

1960 |

73 |

67 |

1.59 |

_ |

|

n/a = information not available |

||||||

As of 8/19, there is a "moderate drought" status for the mid Cape and Nantucket as well as an "abnormally dry" status for the upper and lower Cape and most of Martha's Vinyard : https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?MA

Municipal water restrictions map dated 7/29: https://www.mass.gov/doc/water-use-restrictions-map/download

Phenology

| Indicator Plants - Stages of Flowering (BEGIN, BEGIN/FULL, FULL, FULL/END, END) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLANT NAME (Botanic / Common) | CAPE | S.E. | N.S. | EAST | METRO W. | CENT. | P.V. | BERK. |

|

Clematis paniculata (sweet autumn clematis) |

* |

Begin |

Full |

* |

Begin |

Begin |

Full |

* |

|

Polygonum cuspidatum (Japanese knotweed) |

Begin/Full |

Full |

Full |

Begin |

Full |

Full |

Begin/Full |

* |

|

Clethra alnifolia (summersweet clethra) |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full |

Full |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

|

Hydrangea paniculata (panicle hydrangea) |

Full |

Full/End |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

|

Hibiscus syriacus (rose-of-Sharon) |

Full/End |

End |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full/End |

Full |

|

Lythrum salicaria (purple loosestrife) |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

|

Buddleia davidii (butterfly bush) |

End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

|

Campsis radicans (trumpet vine) |

End |

End |

End |

Full |

Full/End |

* |

End |

Full/End |

| * = no activity to report/information not available | ||||||||

Regional Notes

Cape Cod Region (Barnstable)

General Conditions: The average temperature for the period from August 4 through August 18 was 74˚F with a high of 92˚F on 8/13 and a low of 57˚F on 8/15. The period has had stretches of both hot and oppressive weather as well as periods that are very comfortable. Approximately an inch and a quarter of precipitation fell primarily on 8/4 and 8/5. Soil moisture is still short and the Cape, as of Aug 12, is still listed as partially abnormally dry and partially in moderate drought according to the US Drought Monitor. Woody plants seen in bloom during the period include rose of Sharon, chaste tree, crape myrtle, mimosa, summersweet, butterfly bush, and panicle hydrangea. Herbaceous plants seen in bloom during the period include echinaceae, hosta, Russian sage, achillea, veronicastrum, blue vervain, boneset, beebalm, garden phlox, blacked-eyed Susan, balloon flower, cutleaf coneflower, and hardy hibiscus.

Pests/Problems: Insect pests or damage observed during the period include daylily leaf miner on daylily, euonymus scale on euonymus, black turpentine beetle damage on pitch pine, pine tip moth on pitch pine, hibiscus sawfly on hardy hibiscus and thrips on crocosmia. Disease symptoms or signs observed during the period include powdery mildew on numerous herbaceous and woody plants, black spot on rose, aster yellows on echinacea, cercospora leaf spot on hydrangea, guignardia leaf blotch on horsechestnut, and slime flux on maple. Weeds and wildflowers in bloom include spotted knapweed, chicory, carpetweed, prostrate spurge, Pennsylvania smartweed, annual fleabane, bird’sfoot trefoil, yellow toadflax, Queen Anne’s lace, goldenrod, horseweed, pilewort, mugwort, and perennial sowthistle.

Southeast Region (Dighton)

General Conditions: Although we've been having fierce bouts of summer tropical heat and humidity attendant with booming downpours, signs and wonders portending fall are becoming more prevalent and insistent. Perseids meteor showers at night have been followed by late, dark mornings. Burning bush is starting to color, as are the samaras of Ailanthus and the crowns of sadly declining maples. Small songbirds are flocked together in the hedgerows, fattening on the many seeds and bugs. Mugwort, lamb's quarters, horsetail, and ragweed wave from behind the guardrails. Farm stands are full of baskets brimming with summer fruits and vegetables such as peaches, field tomatoes, and sweet corn. Nurseries are proffering just budding fall mums. Savor these last precious days of summer while you can. One morning soon you'll wake up and try to recall where you left your favorite sweater. Among the many plants in bloom I've noticed these: Albizia julibrissin (mimosa), Alcea rosea (hollyhock), Ambrosia artemisiifolia (annual ragweed), Artemisia vulgaris (mugwort), Buddleja davidii (butterfly bush), Campsis radicans (trumpet vine), Centaurea stoebe (spotted knapweed), Clematis paniculata (autumn clematis), Clethra alnifolia (summersweet), Cyperus esculentus (yellow nutsedge), Daucus carota (Queen Anne's lace), Digitaria (crabgrass), Echinacea purpurea (purple coneflower), Eupatorium perfoliatum (common boneset), Eutrochium purpureum (Joe-pye weed), Franklinia alatamaha (Ben Franklin tree), Helenium autumnale (sneezeweed), Hemerocallis (daylily), Hibiscus syriacus (rose of Sharon), Hosta plantaginea (autumn plantain lily), Hydrangea paniculata (panicled hydrangea), Impatiens capensis (jewelweed), Lagerstroemia (crepe myrtle), Lilium lancifolium (tiger lily), L. orientalis (Oriental lily), Linaria vulgaris (toadflax), Lotus corniculatus (bird's-foot trefoil), Lythrum salicaria (purple loosestrife), Miscanthus sinensis (Chinese silver grass), Monarda didyma (scarlet beebalm), Oenothera biennis (common evening primrose), Panicum (panic grass), Persicaria bicornis (pink smartweed), Phlox paniculata (garden phlox), Hieracium pilosella (yellow hawkweed), Phragmites australis (common reed), Reynoutria japonica, syn. Fallopia japonica, Polygonum cuspidatum (Japanese knotweed), Rhus copallinum (shining sumac), Rosa 'Knockout', Rudbeckia hirta (black-eyed-Susan), Salvia nemorosa (woodland sage), S. yangii (Russian sage), Sedum 'Autumn Joy', S. 'Black Jack', (stonecrop), Solanum carolinense (horse nettle), Solidago (goldenrod), and Tanacetum vulgare (tansy).

Pests/Problems: Crabgrass now has multiple tillers, is in flower and setting seed. Yellow nutsedge is flowering and will have produced nutlets/tubers. Both Japanese knotweed and Phragmites are in full bloom, outcompeting native plants. Ragweed is in bloom which is one of the most common airborne pollen allergens causing people’s itchy eyes at this time of year. The goldenrods that some people still mistakenly think can cause allergies, have pollen that is too heavy to blow in the wind and must be moved by pollinators. Powdery mildew is on garden phlox and lilac. Oriental garden beetle adults are still present. The Bristol County Mosquito Control Project has just found West Nile Virus infected mosquitoes in Dighton.

North Shore (Beverly)

General Conditions: The conditions during this past two-week reporting period were variable. We had some days with hot and humid conditions with temperatures above 90℉ and some pleasant days with comfortable temperatures in the 70s and low humidity. The average daily temperature was 74℉ with the maximum temperature of 92℉ recorded on August 12 and the minimum temperature of 57℉ recorded on August 16. Approximately 1.42 inches of rainfall was recorded at Long Hill during the last two weeks. Woody plants seen in bloom include: silk tree or mimosa (Albizia julibrissin), panicle hydrangea (Hydrangea paniculata), butterfly bush (Buddleia davidii), rose-of-Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus), chaste tree (Vitex agnus-castus), daphne (Daphne spp.), Japanese pagoda tree (Sophora japonica) and summersweet clethra (Clethra alnifolia). Herbaceous plants seen in bloom include: Culver’s root (Veronicastrum virginicum), anemone (Anemonopsis macrophylla), fairy candle (a.k.a. black cohosh, black bugbane or black snakeroot, Actaea racemosa), beebalm (Monarda didyma), shasta daisy (Leucanthemum x superbum), garden phlox (Phlox paniculata), hostas (Hosta spp.), sedums (Sedum spp.), Joe-Pye weed (Eutrochium maculatum), summer flowering roses (Rosa sp.), clematis vines (Clematis paniculata), late blooming/peach-leaved bellflower (Campanula persicifolia), black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta), purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), Heuchera sp., white water lily (Nymphaea odorata) and an assortment of summer annual plants.

Pests/Problems: Leaf blotch was observed on peony and red horsechestnut (Aesculus carnea). Powdery mildew continues to be observed on lilac and phlox, and black spot on roses. Weeds continue to thrive in landscapes. Some of the weeds observed in bloom include: white clover (Trifolium repens), yellow woodsorrel (Oxalis stricta), purslane (Portulaca oleracea), spotted spurge (Euphorbia maculata), bittersweet nightshade (Solanum dulcamara), Japanese knotweed (Polygonum cuspidatum), pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus), ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia) and goldenrod (Solidago spp). Mushrooms were observed growing on lawn areas. Ticks and mosquitoes continue to be very active. Always protect yourself with repellent when working or walking outdoors in the woods.

East Region (Boston)

General Conditions: We experienced our third heat wave of the season on August 11,12 and 13 with temperatures ranging from 90 to 93˚F. Overnight lows never fell below 70˚F from the 11th thru the 14th. This was followed by fall-like conditions with cool mornings and no humidity. Unfortunately, we did not receive any precipitation generally associated with this drastic change in weather conditions. We have received 1.37 inches of precipitation in August, 0.92 inches of which fell on August 5. Albizia julibrissin (mimosa), Salvia yangii, previously known as Perovskia atriplicifolia (Russian sage) and Vitex angus-castus (chaste tree) are in full bloom. Hibiscus moscheutos (hardy hibiscus) is putting on a show. The monocarpic biennial Angelica gigas is getting a lot of attention from pollinators. Noteworthy as a street tree; the unusual late summer flowering Styphnolobium japonicum (Japanese pagoda tree) is in full bloom.

Pests/Problems: We have received 1.37” of precipitation half way through August. The majority, 0.92 inches, fell back on August 5 and our last measurable precipitation was on August 10. Soils are moderately dry. Powdery mildew is prevalent on lilac, monarda and garden phlox. Unmown Japanese knotweed along roadsides is beginning to flower.

Metro West (Acton)

General Conditions: We experienced our third heat wave of the summer last week on the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th with temperatures recorded in the low 90’s. Incidentally, our first 2 heatwaves were recorded in June. The historical monthly average rainfall for August is 3.72”. During this past two-week reporting period, 1.39” of rain was recorded. Observed in some stage of bloom these past two weeks were the following woody plants: Albizia julibrissin (silk tree), Buddleia spp. (butterfly-bush), Clethra alnifolia (summersweet), Hibiscus syriacus (rose-of-Sharon), Hydrangea paniculata (panicle hydrangea) and its many cultivars including 'Tardiva', Potentilla fruiticosa (potentilla), Rosa spp. (rose), R. rugosa (beach rose), R. 'Knockout' (Knockout family of roses), and Styphnolobium japonicum (Japanese pagoda tree). Woody vines observed in bloom include Campsis radicans (trumpet vine) and Clematis paniculata (sweet autumn clematis). Contributing even more color and interest to the landscape are some flowering herbaceous plants including: Alcea rosea (hollyhock), Achillea millefolium (yarrow), Asclepias syriaca (common milkweed), A. tuberosa (butterfly weed), Allium spp. (ornamental onion), Astilbe spp. (false spirea), Boltonia asteroides (Bolton’s aster), Cichorium intybus (chicory), Coreopsis sp. (tickseed), C. verticillata (threadleaf coreopsis), Daucus carota (Queen Anne's lace), Echinacea purpurea (purple coneflower) and its many cultivars, Eutrochium purpureum (Joe-Pye weed), Geranium spp. (cranesbill), Hemerocallis fulva ‘Kwanso’ (double flowering orange daylily), H. 'Stella D'Oro', (daylily), H. spp. (daylily), Hosta spp. (plantain lily), Kirengeshoma palmata (yellow wax bells), Lamium maculatum (dead nettle), Leucanthemum sp. (shasta daisy), Liatris spicata (spike gayfeather), Lysimachia clethroides (gooseneck loosestrife), Lythrum salicaria (loosestrife), Monarda didyma (scarlet beebalm), Nepeta spp. (ornamental catmint), Patrinia gibbosa (patrinia), Salvia yangii, previously known as Perovskia atriplicifolia (Russian sage), Phlox carolina (Carolina phlox), P. paniculata (garden phlox), Physostegia virginiana (obedient plant), Platycodon grandiflorus (balloon flower), Rudbeckia fulgida var. sullivantii 'Goldsturm' (black-eyed Susan), Rudbeckia hirta (black-eyed Susan), Sedum ‘Rosy Glow’ (stonecrop), Senna marilandica (wild senna), Solidago spp. (goldenrod), Tanacetum vulgare (tansy), and Veronicastrum virginicum (Culver’s root).

Pests/Problems: Observed in the landscape these past two weeks were leaf blotch on Aesculus sp. (horsechestnut) and sawfly on Betula nigra (river birch). Amelanchier spp. (serviceberry) and Crataegus spp. (hawthorn) displayed fungal fruiting bodies probably caused by cedar-quince rust or possibly by cedar-apple rust. Cedar-quince rust (common on hawthorn and serviceberry) often attacks the fruit and distorts the shoot tips. For more information, see: https://hort.extension.wisc.edu/articles/cedar-apple-rust/ .

Central Region (Boylston)

General Conditions: This past reporting period has been warmer and drier with temperatures mostly staying within a range of lows of mid- to high 60’s and highs of mid-70’s to 80’s. A few days peaked into the 90’s. A few overcast days came with negligible precipitation making watering a must for late plantings and new trees. However, the landscape remains lush and beautiful, especially when compared to how things looked at this time last year. Summer pollinators are in their splendor, nectaring on Eutrochium spp. (Joe-pye weed), Pycnanthemum spp. (mountain mint) and Lobelia, all of which are having a fantastic year here at the garden. We are watching path edges light up with Solidago juncea and S. nemoralis while Solidago canadensis begins to make our meadows twinkle before later species erupt into the pre-fall nectar flow. It’s also important to remember the fall equinox is still a month away, even though we are seeing a few trees begin to develop their fall color.

Pests/Problems: July’s wet weather has created a favorable environment for slugs, snails, midges and mosquitoes - the latter two making work in the garden difficult even with repellant or a stiff breeze. Lower leaves of herbaceous perennials are falling victim to foliar diseases, especially powdery mildew on Monarda and Phlox.

Pioneer Valley Region (Amherst)

General Conditions: Dry, humid and hot best characterizes this past reporting period as we cross the August midpoint in the Pioneer Valley. Another significant heat wave, our third of the summer, settled into the Connecticut Valley from 8/11–8/14. The worst of the heat occurred in the late afternoon on Thursday, 8/12 when the ambient air temperature (96°F) and dew point (73°F) created a heat index value of 106°F, recorded at Barnes Airport in Westfield. By early evening, a powerful band of fast-moving thunderstorms swept through the state, bringing intense rainfall, a barrage of lightning, strong winds, and power outages throughout the region. It was our only rain of the reporting period and a great deal was likely lost to runoff. The storm did nothing to alleviate the muggy conditions and it wasn’t until late in the day on Saturday, 8/15 that the humidity finally cleared out. We then enjoyed a pair of dream-like, late summer days on 8/16 and 8/17. This time of year, especially as we enter September, the decreasing sun angle can make the sun feel more intense in the afternoon. The nice weather didn’t last long though, as dew points were back on the rise at the time of writing with the remnants of Tropical Storm Fred approaching from the south. The storm is predicted to bring heavy rain, which is needed right now as soils are really drying out. Rainfall was sparse during the first half of August and turfgrasses are rapidly browning. Speaking of rain, July of 2021 was officially crowned by the National Centers for Environmental Information as the wettest July on record, with a statewide average of 10.30″. This record-busting total was nearly three times the monthly average (3.68″) and easily surpassed the previous high of 8.96″ recorded in 1938. We are entering an ideal period for transplanting many landscape conifers. By transplanting in late summer to early fall, the root system has some time to establish before the winter freeze. However, avoid transplanting hemlocks and yews at this time, as they often (although not always) transplant more successfully in the spring.

Pests/Problems: The vast majority of landscape trees and shrubs appear fairly healthy right now, likely owing that to the heavy rainfall in July. However, this is the time of year when the rigors of the growing season are on full display. Leaf spots/blotches, insect feeding damage, branch dieback, and early fall color, among other symptoms, are easy to find. Late summer is simply not a time to expect deciduous trees and shrubs to look their best. Oaks showing symptoms of stress should be scouted carefully, as the cause could be the result of several issues. Locally, lace bugs and spider mites may be present on the foliage in high numbers. Generally, these are not considered serious pests of landscape oaks. Symptoms of Tubakia leaf blotch (reddish, circular spots, blotches and marginal blights) are intensifying as the disease develops. Despite infections taking place in the spring, symptoms of Tubakia leaf blotch appear later in the growing season. A widespread outbreak of oak leaf blister is still evident on many trees. Oak shothole leafminer activity was locally abundant again this year throughout the valley and subsequent anthracnose infections established on certain trees. White oaks may have a trifecta of oak shothole leafminer, anthracnose (which is more severe on white oaks) and a significant infestation of the jumping oak gall wasp. If oaks are exhibiting scattered shoot tip dieback and have leaves covered in sooty mold, scout small diameter stems and branches for soft-bodied lecanium scales (most likely the oak lecanium scale). Lecanium scale populations on oak appear to be on the rise in the tri-counties. Feeding by the scale often leads to stem and branch cankering caused by Diplodia corticola. For other landscape trees and shrubs, a variety of late season foliar diseases may develop but are of little consequence. One example is downy leaf spot of hickory, caused by Microstroma juglandis (pictured below). Serviceberry lace bug is common on shrub and tree form plants on the UMass campus. Late summer is an especially important time to scout for ground nesting yellowjackets in the landscape. The eastern yellowjacket (Vespula maculifrons) is one of several that builds large underground nests. In some cases, small mammal burrows (vole, chipmunk and mole) are used to establish nest sites. Swarming yellowjackets will aggressively defend the nest if disturbed by a lawnmower, garden hose, or foot traffic, stinging repeatedly. Scout the edges of landscape beds, pools, deck stairs, etc. prior to working in these areas. The dry weather has helped a bit in suppressing mosquito populations but they still remain very abundant.

Berkshire Region (Great Barrington)

General Conditions: The past two weeks have been closer to what is expected at mid-summer. Temperature range at the northern end of Berkshire County (North Adams Airport) during the interval from August 4-17 was 91˚F on 8/12 to a low of 51˚F on the morning of 8/15. At mid-county (Pittsfield Airport), temperatures ranged from 89˚F on 8/12 to lows of 53˚F on 8/15 and 16. Data from Richmond shows a high of 90˚F on 8/12 and 13 with a low of 51˚F on the 8/15. Rainfall varied considerably throughout the county. Here in West Stockbridge, the total for the scouting period was 1.47 inches with 1.31 inches of that coming from a very heavy but relatively brief thunderstorm in the late afternoon of August 12th. Other locations reported total rainfall from August 4 through the 17th as follows: North Adams 0.51 inches, Pittsfield 0.38 inches, and Richmond 0.73 inches. Such discrepancies are not unusual for a county which extends from Connecticut at its southern border up to Vermont at its northern border. Such variations can also be accounted for by the varied topography, i.e. mountains and valleys. Growth of turfgrass, annuals and herbaceous perennials, and vegetable crops accelerated due to moist but not saturated soils. However, weed growth also accelerated and many are now flowering or have set seed.

Pests/Problems: Growth of plants at this point in the season varies considerably. Much has to do with the drainage properties of soil at different sites. Plants on poorly drained sites with heavy soils are showing very slow growth while those on sandy loams are doing very well for the most part. Regardless of soil texture and drainage features, some plants are showing symptoms of nutrient deficiency, most likely due to soil nutrient leaching caused by the persistent and often heavy rain storms in July. Root rot is not an uncommon occurrence. Plant diseases observed during scouting include: powdery mildew on Monarda, root rot of lavender, cedar-quince rust on hawthorn, phomopsis blight on grapes, anthracnose on Cotinus, black spot on rose foliage, and many and varied leaf spot diseases on maples, beech, and magnolia trees. Plant pest issues observed include red aphids on Helenium, Japanese beetles on roses and other plants though the numbers have decreased over the past 2 weeks, elongate hemlock scale, cabbage worms on ornamental kale, and slugs everywhere. The mosquito population has been very high this summer. Another problem related to the heavy rains of July has been serious soil erosion. Garden plantings on slopes often have gullies where soil has been washed away and sometimes exposing the roots of plants. This has led to wilting and often desiccation of plants. Small animal problems, i.e. chipmunks, voles, mice, are quite common as they feed on a variety of vegetation especially in vegetable gardens.

Regional Scouting Credits

- CAPE COD REGION - Russell Norton, Horticulture and Agriculture Educator with Cape Cod Cooperative Extension, reporting from Barnstable.

- SOUTHEAST REGION - Brian McMahon, Arborist, reporting from the Dighton area.

- NORTH SHORE REGION - Geoffrey Njue, Green Industry Specialist, UMass Extension, reporting from the Long Hill Reservation, Beverly.

- EAST REGION - Kit Ganshaw & Sue Pfeiffer, Horticulturists reporting from the Boston area.

- METRO WEST REGION – Julie Coop, Forester, Massachusetts Department of Conservation & Recreation, reporting from Acton.

- CENTRAL REGION - Mark Richardson, Director of Horticulture reporting from Tower Hill Botanic Garden, Boylston.

- PIONEER VALLEY REGION - Nick Brazee, Plant Pathologist, UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab, reporting from Amherst.

- BERKSHIRE REGION - Ron Kujawski, Horticultural Consultant, reporting from Great Barrington.

Woody Ornamentals

Diseases

Recent pests and pathogens of interest seen in the UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab https://ag.umass.edu/services/plant-diagnostics-laboratory:

Stem cankering and leaf blotch in the canopy of a Mongolian oak (Quercus mongolica), caused by Diplodia corticola and Tubakia. The tree is 98-years-old and has been present at the site for 93 years. It receives full sun in a low, sometimes poorly-drained site. Scattered cankering and branch dieback is evident in the canopy and the symptoms have been present in years past. Diplodia can create numerous, eruptive stem and branch cankers on a variety of oak species, but is nearly always found on oaks suffering from various abiotic and insect-related stresses.

Stem cankering and leaf blotch in the canopy of a Mongolian oak (Quercus mongolica), caused by Diplodia corticola and Tubakia. The tree is 98-years-old and has been present at the site for 93 years. It receives full sun in a low, sometimes poorly-drained site. Scattered cankering and branch dieback is evident in the canopy and the symptoms have been present in years past. Diplodia can create numerous, eruptive stem and branch cankers on a variety of oak species, but is nearly always found on oaks suffering from various abiotic and insect-related stresses.

- Oak anthracnose (Apiognomonia errabunda) and Tubakia leaf blotch (Tubakia sp.) on white oak (Quercus alba). The tree is approximately nine-years-old and has been present at the site for six years. It was planted near a 3’ stone wall in a managed pasture, with full sun and well-drained soil. In late spring of 2019, the tree first developed symptoms of anthracnose and the disease was confirmed by an arborist. The disease developed again in 2020 but no action was taken. In 2021, chlorothalonil was applied to the foliage in May but the disease appeared yet again. Diseased leaves have also been removed each year to reduce inoculum. White oaks are particularly susceptible to oak anthracnose and despite good growing conditions, the disease remains stubbornly persistent. A more aggressive fungicide treatment, beginning before bud break and continuing on regular intervals throughout the spring season, should help to reduce disease severity in the future. The canopy is small and can be readily treated with minimal drift.

- Glyphosate exposure to a wide array of plants in a private landscape. Submitted plant samples included rose-of-Sharon (Hibiscus syriacus), dogwood (Cornus) and birch (Betula). But, numerous other plants were exposed, including oak, rhododendron and white pine. The symptoms included tufted, stunted and deformed foliage, along with major canopy dieback. The symptoms were distinctive to glyphosate and no disease or insect pests were present. The property was neglected for many years and during the restoration process, the plants were exposed to this systemic herbicide. Even minor amounts of glyphosate drift can cause injury. In some cases of non-lethal exposure, plants can outgrow the injury over time. However, based on the submitted samples, many of these trees and shrubs will not survive.

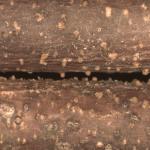

Cottony camellia scale (Pulvinaria floccifera) and sooty mold on Hicks yew (Taxus × media ‘Hicksii’).Infestation of the cottony camellia scale (Pulvinaria floccifera) on Hicks yew (Taxus × media ‘Hicksii’). Shrub border on the west-facing side of a building with good sun exposure and no supplemental irrigation. The cottony camellia scale (also known as the cottony taxus scale) is often highly conspicuous, with the white, woolly scales contrasting against the dark green color of infested leaves/needles. There was a significant coating of sooty mold, non-pathogenic fungi that grow on the surface to consume honeydew deposited by the scales. The canopies are thinning due to the infestation and will be treated accordingly to suppress the scale population.

Cottony camellia scale (Pulvinaria floccifera) and sooty mold on Hicks yew (Taxus × media ‘Hicksii’).Infestation of the cottony camellia scale (Pulvinaria floccifera) on Hicks yew (Taxus × media ‘Hicksii’). Shrub border on the west-facing side of a building with good sun exposure and no supplemental irrigation. The cottony camellia scale (also known as the cottony taxus scale) is often highly conspicuous, with the white, woolly scales contrasting against the dark green color of infested leaves/needles. There was a significant coating of sooty mold, non-pathogenic fungi that grow on the surface to consume honeydew deposited by the scales. The canopies are thinning due to the infestation and will be treated accordingly to suppress the scale population.

- Verticillium wilt of cork tree (Phellodendron amurense) caused by Verticillium dahliae. The tree is roughly 35-years-old and resides in a park setting with full sun and irrigation. This is one of three cork trees at the site and in previous years, no major health issues have been observed. This season, premature leaf shedding occurred throughout half of the canopy and vascular staining was observed in various branch sections. When trees are young, infected portions of the canopy can sometimes be pruned out, successfully controlling the disease. But on a larger and older tree such as this one, pruning is unlikely to contain the infection.

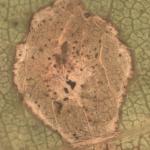

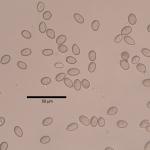

Phomopsis cankering of Japanese maple (Acer palmatum). The tree was transplanted approximately 30 years ago to an ocean front site along Buzzards Bay. Despite the location, the tree is shielded from direct ocean exposure by a house. The tree receives full sun in sandy soils but does receive some supplemental irrigation from lawn sprinklers. The tree had been healthy for many years but developed symptoms of canopy dieback after the 2016 drought. Through good care, the tree bounced back in 2017 and was healthy until this past spring. Once again, drought from 2020 is suspected of predisposing the tree to stress. The submitted stems and branches were desiccated with pale brown vascular tissue. After a short incubation, numerous spore masses ruptured through the bark on diseased stems (see photo). Phomopsis canker on Japanese maple has been especially common in 2021 with stress from last summer’s heat and drought facilitating disease development.

Phomopsis cankering of Japanese maple (Acer palmatum). The tree was transplanted approximately 30 years ago to an ocean front site along Buzzards Bay. Despite the location, the tree is shielded from direct ocean exposure by a house. The tree receives full sun in sandy soils but does receive some supplemental irrigation from lawn sprinklers. The tree had been healthy for many years but developed symptoms of canopy dieback after the 2016 drought. Through good care, the tree bounced back in 2017 and was healthy until this past spring. Once again, drought from 2020 is suspected of predisposing the tree to stress. The submitted stems and branches were desiccated with pale brown vascular tissue. After a short incubation, numerous spore masses ruptured through the bark on diseased stems (see photo). Phomopsis canker on Japanese maple has been especially common in 2021 with stress from last summer’s heat and drought facilitating disease development.

Report by Nick Brazee, Plant Pathologist, UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab, UMass Amherst.

Insects

Really Cool Insect Sighting:

Giant Ichneumonid Wasps: Wasps in the genus Megarhyssa are some of the most impressive and striking in the Family Ichneumonidae. While the ovipositor (egg-laying structure) of this native insect is fantastically long, do not let it frighten you. Giant ichneumonid wasps use these structures to pierce through the wood of trees, and into the larvae of the pigeon tremex horntail or other wood wasps that develop in stressed or recently dead tree limbs or trunks. So these giant parasitic wasps help regulate wood boring wasp populations, and are not tree pests themselves. (Their larvae feed on the developing wood wasp larvae, which perish as a result of being fed upon.) They are also incapable of stinging humans- so again there is no need to fear their lengthy “stingers” that can be 2 times the length of their own bodies! There are two similar species in this genus that the insect in this photo is likely one of: Megarhyssa macrurus and M. greenei. To tell the difference, one needs to look carefully at the pigmentation on the wings of these insects for differentiation between the two species. Another clue is that Megarhyssa macrurus females have an ovipositor that can be 2X the length of their entire bodies, whereas M. greenei has an ovipositor that is only approximately 1.5X the length of her body.

Giant Ichneumonid Wasps: Wasps in the genus Megarhyssa are some of the most impressive and striking in the Family Ichneumonidae. While the ovipositor (egg-laying structure) of this native insect is fantastically long, do not let it frighten you. Giant ichneumonid wasps use these structures to pierce through the wood of trees, and into the larvae of the pigeon tremex horntail or other wood wasps that develop in stressed or recently dead tree limbs or trunks. So these giant parasitic wasps help regulate wood boring wasp populations, and are not tree pests themselves. (Their larvae feed on the developing wood wasp larvae, which perish as a result of being fed upon.) They are also incapable of stinging humans- so again there is no need to fear their lengthy “stingers” that can be 2 times the length of their own bodies! There are two similar species in this genus that the insect in this photo is likely one of: Megarhyssa macrurus and M. greenei. To tell the difference, one needs to look carefully at the pigmentation on the wings of these insects for differentiation between the two species. Another clue is that Megarhyssa macrurus females have an ovipositor that can be 2X the length of their entire bodies, whereas M. greenei has an ovipositor that is only approximately 1.5X the length of her body.

Insects and Other Arthropods of Medical Importance:

- Mosquitoes: The Massachusetts Department of Public Health announced on July 1, 2021 that West Nile virus (WNV) was detected in mosquitoes in Massachusetts for the first time this year in a sample collected on June 29 in the town of Medford, MA (Middlesex County). To date, no human or animal cases of WNV or Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE) have been detected so far in 2021. For more information, visit: https://www.mass.gov/news/state-public-health-officials-confirm-seasons-first-west-nile-virus-positive-mosquito-sample .

WNV positive mosquito samples have been identified in Barnstable, Bristol, Essex, Hampden, Hampshire, Middlesex, Norfolk, Plymouth, Suffolk, and Worcester Counties. WNV risk levels have increased to moderate for communities in the Greater Boston area due to increasing WNV activity in mosquitoes. Please view the risk maps available here for updates: https://www.mass.gov/info-details/massachusetts-arbovirus-update .

According to the Massachusetts Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Science and the Department of Public Health, there are at least 51 different species of mosquito found in Massachusetts. Mosquitoes belong to the Order Diptera (true flies) and the Family Culicidae (mosquitoes). As such, they undergo complete metamorphosis, and possess four major life stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Adult mosquitoes are the only stage that flies and many female mosquitoes only live for 2 weeks (although the life cycle and timing will depend upon the species). Only female mosquitoes bite to take a blood meal, and this is so they can make eggs. Mosquitoes need water to lay their eggs in, so they are often found in wet or damp locations and around plants. Different species prefer different habitats. It is possible to be bitten by a mosquito at any time of the day, and again timing depends upon the species. Many are particularly active from just before dusk, through the night, and until dawn. Mosquito bites are not only itchy and annoying, but they can be associated with greater health risks. Certain mosquitoes vector pathogens that cause diseases such as West Nile virus (WNV) and eastern equine encephalitis (EEE).

For more information about mosquitoes in Massachusetts, visit: https://www.mass.gov/service-details/mosquitoes-in-massachusetts .

There are ways to protect yourself against mosquitoes, including wearing long-sleeved shirts and long pants, keeping mosquitoes outside by using tight-fitting window and door screens, and using insect repellents as directed. Products containing the active ingredients DEET, permethrin, IR3535, picaridin, and oil of lemon eucalyptus provide protection against mosquitoes.

For more information about mosquito repellents, visit: https://www.mass.gov/service-details/mosquito-repellents and https://www.cdc.gov/mosquitoes/mosquito-bites/prevent-mosquito-bites.html .

- Deer Tick/Blacklegged Tick: Check out the archived TickTalk with TickReport webinars available here: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/webinars .

*Ixodes scapularis - We are now in the time of year when deer tick larvae and nymphs are frequently encountered. Larvae may be encountered in April, but in some locations may peak in their activity in August, while still being encountered through November. Nymphs are encountered from April through July, peaking in June. Nymphs are again present in October and November. For images of all deer tick life stages, along with an outline of the diseases they carry, and their timing of activity, visit: http://www.tickencounter.org/tick_identification/deer_tick .

Anyone working in the yard and garden should be aware that there is the potential to encounter deer ticks. The deer tick or blacklegged tick can transmit Lyme disease, human babesiosis, human anaplasmosis, and other diseases. Preventative activities, such as daily tick checks, wearing appropriate clothing, and permethrin treatments for clothing (according to label instructions) can aid in reducing the risk that a tick will become attached to your body. If a tick cannot attach and feed, it will not transmit disease. For more information about personal protective measures, visit: http://www.tickencounter.org/prevention/protect_yourself .

The Center for Agriculture, Food, and the Environment provides a list of potential tick identification and testing resources here: https://ag.umass.edu/resources/tick-testing-resources .

*Note that deer ticks (Ixodes scapularis) are not the only disease-causing tick species found in Massachusetts. The American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis) and the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) are also found throughout MA. Each can carry their own complement of diseases, including others not mentioned above. Anyone working or playing in tick habitats (wood-line areas, forested areas, and landscaped areas with ground cover) should check themselves regularly for ticks while practicing preventative measures.

American Dog Tick: Anecdotally, Dermacentor variabilis has been prevalent in certain locations in Massachusetts in 2021. The images shown here are adult stage dog ticks removed from a dog following a roadside walk in Hampshire County on both 5/6/21 (4 ticks removed) and 5/7/21 (3 ticks removed). Looking for more updates? Check out UMass Extension’s Tick Check with Blake Dinius, Plymouth County Extension Service and Larry Dapsis, Cape Cod Cooperative Extension: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gryCv8qB1qw .

American Dog Tick: Anecdotally, Dermacentor variabilis has been prevalent in certain locations in Massachusetts in 2021. The images shown here are adult stage dog ticks removed from a dog following a roadside walk in Hampshire County on both 5/6/21 (4 ticks removed) and 5/7/21 (3 ticks removed). Looking for more updates? Check out UMass Extension’s Tick Check with Blake Dinius, Plymouth County Extension Service and Larry Dapsis, Cape Cod Cooperative Extension: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gryCv8qB1qw .

The American dog tick is found throughout most of North America. It may be encountered in forest edges, fields, along walkways and roadways, sidewalks, and trails. Adult stage ticks may be found on raccoons, skunks, cats, dogs, and other medium-sized hosts. Larvae and nymphs can be found on mice, voles, rats, and chipmunks. Adult males and females are active between April and early-August. Both adult males and females will feed, including on people. Nymphs and larvae of this species rarely attach to people or their pets. This species of tick can transmit lesser-known diseases such as Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (not frequently infecting humans, according to CDC reports) and Tularemia (rarely infecting humans, according to CDC reports). For more information about the American dog tick, visit: https://web.uri.edu/tickencounter/species/dog-tick/ .

Wasps/Hornets: Many wasps are predators of other arthropods, including pest insects such as certain caterpillars that feed on trees and shrubs. Adult wasps hunt prey and bring it back to their nest where young are being reared, as food for the immature wasps. A common such example are the paper wasps (Polistes spp.) who rear their young on chewed up insects. They may be seen searching plants for caterpillars and other soft-bodied larvae to feed their young. Paper wasps can sting, and will defend their nests, which are open-celled paper nests that are not covered with a papery “envelope”. These open-celled nests may be seen hanging from eaves or other outdoor building structures, however these insects sometimes find the most interesting locations to construct their nests. These photos taken on 8/15/2021 show a paper wasp nest that was located at the end of a cannon at a town memorial park in Hampshire County, MA. So expect these nests in the oddest of locations to avoid being stung! Aerial yellow jackets and hornets create large aerial nests that are covered with a papery shell or “envelope”. Common yellow jacket species include those in the genus Vespula. Dolichovespula maculata is commonly known as the baldfaced hornet, although it is not a true hornet.

Wasps/Hornets: Many wasps are predators of other arthropods, including pest insects such as certain caterpillars that feed on trees and shrubs. Adult wasps hunt prey and bring it back to their nest where young are being reared, as food for the immature wasps. A common such example are the paper wasps (Polistes spp.) who rear their young on chewed up insects. They may be seen searching plants for caterpillars and other soft-bodied larvae to feed their young. Paper wasps can sting, and will defend their nests, which are open-celled paper nests that are not covered with a papery “envelope”. These open-celled nests may be seen hanging from eaves or other outdoor building structures, however these insects sometimes find the most interesting locations to construct their nests. These photos taken on 8/15/2021 show a paper wasp nest that was located at the end of a cannon at a town memorial park in Hampshire County, MA. So expect these nests in the oddest of locations to avoid being stung! Aerial yellow jackets and hornets create large aerial nests that are covered with a papery shell or “envelope”. Common yellow jacket species include those in the genus Vespula. Dolichovespula maculata is commonly known as the baldfaced hornet, although it is not a true hornet.

The European hornet (Vespa crabro) is three times the size of a yellow jacket and may be confused for the Asian giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia). The European hornet is known to Massachusetts, but the Asian giant hornet is not. If you are concerned that you have found or photographed an Asian giant hornet, please report it here: https://massnrc.org/pests/report.aspx . Paper wasps and aerial yellowjackets overwinter as fertilized females (queens) and a single female produces a new nest annually in the late spring. Nests are abandoned at the end of the season. Queens start new nests, lay eggs, and rear new wasps to assist in colony/nest development.Some people are allergic to stinging insects, so care should be taken around wasp/hornet nests. Unlike the European honeybee (Apis mellifera), wasps and hornets do not have barbed stingers, and therefore can sting repeatedly when defending their nests. It is best to avoid their nests, and if that cannot be done and assistance is needed to remove them, consult a professional.

The European hornet (Vespa crabro) is three times the size of a yellow jacket and may be confused for the Asian giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia). The European hornet is known to Massachusetts, but the Asian giant hornet is not. If you are concerned that you have found or photographed an Asian giant hornet, please report it here: https://massnrc.org/pests/report.aspx . Paper wasps and aerial yellowjackets overwinter as fertilized females (queens) and a single female produces a new nest annually in the late spring. Nests are abandoned at the end of the season. Queens start new nests, lay eggs, and rear new wasps to assist in colony/nest development.Some people are allergic to stinging insects, so care should be taken around wasp/hornet nests. Unlike the European honeybee (Apis mellifera), wasps and hornets do not have barbed stingers, and therefore can sting repeatedly when defending their nests. It is best to avoid their nests, and if that cannot be done and assistance is needed to remove them, consult a professional.

Woody ornamental insect and non-insect arthropod pests to consider, a selected few:

Invasive Insects & Other Organisms Update:

![Box tree moth adult. (Matteo Maspero and Andrea Tantardini, Centro MiRT Fondazione Minoprio [IT]) Box tree moth adult. (Matteo Maspero and Andrea Tantardini, Centro MiRT Fondazione Minoprio [IT])](/sites/ag.umass.edu/files/styles/150x150/public/pest-alerts/images/content/box_tree_moth_courtesy_of_matteo_maspero_and_andrea_tantardini_centro_mirt_fondazione_minoprio_it.jpg?itok=pIFkiiQi)

![Box tree moth caterpillars. (Matteo Maspero and Andrea Tantardini, Centro MiRT Fondazione Minoprio [IT]) Box tree moth caterpillars. (Matteo Maspero and Andrea Tantardini, Centro MiRT Fondazione Minoprio [IT])](/sites/ag.umass.edu/files/styles/150x150/public/pest-alerts/images/content/box_tree_moth_caterpillar_courtesy_of_matteo_maspero_and_andrea_tantardini_centro_mirt_fondazione_minoprio_it.jpg?itok=BDTKHKwy) Box Tree Moth: Cydalima perspectalis is native to East Asia. It has become a serious invasive pest in Europe, where it continues to spread. The caterpillars feed mostly on boxwood, and heavy infestations can defoliate host plants. Once the leaves are gone, larvae consume the bark, leading to girdling and plant death. The box tree moth is not currently known to be established in Massachusetts, however the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) is urging professionals and citizens to report any suspicious insects.

Box Tree Moth: Cydalima perspectalis is native to East Asia. It has become a serious invasive pest in Europe, where it continues to spread. The caterpillars feed mostly on boxwood, and heavy infestations can defoliate host plants. Once the leaves are gone, larvae consume the bark, leading to girdling and plant death. The box tree moth is not currently known to be established in Massachusetts, however the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) is urging professionals and citizens to report any suspicious insects.

To report suspected box tree moth life stages or damage to boxwood in Massachusetts, please visit: https://massnrc.org/pests/pestreports.htm .

Females lay eggs singly or in clusters of 5 to more than 20 eggs in a gelatinous mass on the underside of boxwood leaves. Most females deposit more than 42 egg masses in their lifetime. They typically hatch within 4 to 6 days. Pupae typically first appear in April or May and are present continuously through the summer and into the fall, depending on the local climate and timing of generations. Adults first emerge from the overwintering generation between April and July, depending on climate and temperature. Subsequent generations are active between June and October. Adults typically live for two weeks after emergence. The exact timing of the life cycle of this insect in Massachusetts is not currently known.

The Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources (MDAR) recently reported that the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) has confirmed the presence of box tree moth in the continental United States and is taking action alongside state partners and industry to contain and eradicate the invasive pest that was imported on nursery plants shipped from Ontario, Canada. For a recent press release regarding this insect from the MA Department of Agricultural Resources, visit: https://www.mass.gov/news/state-agricultural-officials-urge-public-to-inspect-boxwood-shrubs-for-box-tree-moths .

Between August 2020 and April 2021, a nursery in St. Catharines, Ontario shipped boxwood (Buxus species) that may have been infested with box tree moth to locations in six states—25 retail facilities in Connecticut, Massachusetts, Michigan, New York, Ohio, and South Carolina—and a distribution center in Tennessee. At this time, the pest has been identified in three facilities in Michigan, one in Connecticut, and one in South Carolina, and APHIS is working with state plant regulatory officials to determine whether other facilities may be impacted. For more information, visit: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/newsroom/stakeholder-info/sa_by_date/sa-2021/sa-05/box-tree-moth .

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid: Adelges tsugae is an invasive pest found on eastern and Carolina hemlock. Hemlock woolly adelgid populations were reportedly very high in certain locations across Massachusetts and much of New England this year. UMass Extension has fielded many reports of infested trees and questions about HWA management. A fascinating story about hemlock woolly adelgid has developed and was recently shared with UMass Extension by our friends at the Maine Forest Service:

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid: Adelges tsugae is an invasive pest found on eastern and Carolina hemlock. Hemlock woolly adelgid populations were reportedly very high in certain locations across Massachusetts and much of New England this year. UMass Extension has fielded many reports of infested trees and questions about HWA management. A fascinating story about hemlock woolly adelgid has developed and was recently shared with UMass Extension by our friends at the Maine Forest Service:

In June, 2021, news articles began appearing regarding a strange phenomenon of beachgoers in southern Maine experiencing their bare feet being stained black as they walked along the beach. (See photos in the article: “What’s staining the feet of southern Maine beachgoers? DEP officials investigating.” by Steven Porter and Camille Fine, Portsmouth Herald on June 9, 2021.) Well, the Maine Forest Service released in their July 22, 2021 Conditions Report under “Insects” the following statement:

“Remember that bizarre story about beach-goers in Southern Maine going home with stained and blackened feet? Well, there’s a new plot twist – it seems that the billions of tiny insects washing up on our beaches were none other than hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA) adults.

When we first received samples of the insects from Wells Beach, we weren’t quite sure what they were. Once we saw them, our original sight-unseen hypothesis that they might be a species of kelp fly went right out the window. These tiny insects were clearly true bugs and had two pairs of wings, immediately disqualifying any sort of fly. Karen Coluzzi, in the Cooperative Agricultural Pest Survey program, initially suggested Adelgidae, which was confirmed by USFS. We sent a sample to Nathan Havill for DNA-barcoding and after several inconclusive results from the deteriorating sample, a clear read came back with a clear answer – these weren’t any of our other common native adelgids, but the invasive HWA.

Many adelgids have complex life cycles with multiple forms, including both winged (alate) and non-winged forms. In its native range, HWA has multiple host trees, and the winged adults are those that leave hemlock trees to go in search of certain spruce species, which serves as their primary host species. In North America these particular spruce species are absent, so the good news is, this life stage is a dead end.”

The entire Conditions Report from the Maine Forest Service is available here: https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/MEDACF/bulletins/2e96444 Thank you Maine Forest Service for sharing such an interesting story!

Additionally, Dr. David Orwig (Forest Ecologist, Harvard Forest) shared that he experienced sexuparae (winged HWA) flights on June 11, 2021 in Petersham, MA where HWA populations were also very high this year. He noted that the winged individuals quickly coated the front of a vehicle. (Personal Communication.) Some news reports also indicate that this phenomenon might have been experienced at beaches in coastal parts of Massachusetts, including Gloucester and Beverly, MA.

HWA Biology/Life Cycle Reminders: The overwintering hemlock woolly adelgid generation (sistens) is present through mid-spring and produces the spring generation (progrediens) which is present from early spring through mid-summer. HWA, unlike many other insects, does most of its feeding over the winter. Eggs may be found in woolly masses at the base of hemlock needles beginning in mid-March. Each woolly mass is created by a female who may then lay 50-300 eggs. Eggs hatch and crawlers may be found from mid-March through mid-July. Infested trees may be treated with foliar sprays in late April to early May, using Japanese quince as a phenological indicator. Systemic applications may be made in the spring and fall, or when soil conditions are favorable for translocation to foliage. Nitrogen fertilizer applications may make hemlock woolly adelgid infestations worse.

Spotted Lanternfly: (Lycorma delicatula, SLF) is not known to be established in Massachusetts landscapes at this time. However, due to the great ability of this insect to hitchhike using human-aided movement, it is important that we remain vigilant in Massachusetts and report any suspicious findings. Spotted lanternfly reports can be sent here: https://massnrc.org/pests/slfreport.aspx .

Spotted Lanternfly: (Lycorma delicatula, SLF) is not known to be established in Massachusetts landscapes at this time. However, due to the great ability of this insect to hitchhike using human-aided movement, it is important that we remain vigilant in Massachusetts and report any suspicious findings. Spotted lanternfly reports can be sent here: https://massnrc.org/pests/slfreport.aspx .

The Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources has recently released spotted lanternfly Best Management Practices for Nurseries and Landscapers: https://massnrc.org/pests/linkeddocuments/MANurseryBMPs.pdf

And Best Management Practices for Moving Companies and the Moving Industry: https://massnrc.org/pests/linkeddocuments/SLFChecklistMovingIndustryMA.pdf

Now is a great time to provide copies of these BMP’s to employees, customers, family, and friends! The more eyes we have out there looking for spotted lanternfly, the better. Use the above BMP’s as a guide to help you inspect certain items coming from CT, DE, MD, NC, NJ, NY, OH, PA, WV, and VA.

UMass Extension is teaming up with UMass Amherst’s Department of Environmental Conservation, the USDA APHIS, and the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources to monitor for the spotted lanternfly in Massachusetts. A team including members of UMass Extension’s Landscape, Nursery, and Urban Forestry Program, Extension’s Fruit Program, Stockbridge School of Agriculture, and the Department of Environmental Conservation at UMass, Amherst are undertaking a nine-month integrated research and extension project to develop effective tools to detect the spotted lanternfly.

The researchers associated with this project (Dr. Joseph Elkinton, Dr. Jeremy Andersen and Dr. Jaime Pinero) will be working with Dr. Miriam Cooperband of the USDA APHIS lab on Cape Cod to identify and evaluate airborne attractants that can improve the ability to detect SLF in traps. Dr. Cooperband has identified several attractant lures released from host plants of SLF. She is currently working on pheromones produced by SLF that may be much more attractive. The UMass team will help her conduct field tests of these new lures, while also assisting the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources (MDAR) in monitoring for SLF in Massachusetts. UMass Extension Entomologist, Tawny Simisky, will periodically report on progress made during the course of this project. For more information, please visit: https://ag.umass.edu/cafe/news/looking-for-spotted-lanternfly-recent-invasive-arrival .

This insect is a member of the Order Hemiptera (true bugs, cicadas, hoppers, aphids, and others) and the Family Fulgoridae, also known as planthoppers. The spotted lanternfly is a non-native species first detected in the United States in Berks County, Pennsylvania and confirmed on September 22, 2014.

For a map of known, established populations of SLF as well as detections outside of these areas where individual finds of spotted lanternfly have occurred (but no infestations are present), visit: https://nysipm.cornell.edu/environment/invasive-species-exotic-pests/spotted-lanternfly/ .

The spotted lanternfly is considered native to China, India, and Vietnam. It has been introduced as a non-native insect to South Korea and Japan, prior to its detection in the United States. In South Korea, it is considered invasive and a pest of grapes and peaches. The spotted lanternfly has been reported feeding on over 103 species of plants, according to new research (Barringer and Ciafré, 2020) and when including not only plants on which the insect feeds, but those that it will lay egg masses on, this number rises to 172. This includes, but is not limited to, the following: tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) (preferred host), apple (Malus spp.), plum, cherry, peach, apricot (Prunus spp.), grape (Vitis spp.), pine (Pinus spp.), pignut hickory (Carya glabra), sassafras (Sassafras albidum), serviceberry (Amelanchier spp.), slippery elm (Ulmus rubra), tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera), white ash (Fraxinus americana), willow (Salix spp.), American beech (Fagus grandifolia), American linden (Tilia americana), American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis), big-toothed aspen (Populus grandidentata), black birch (Betula lenta), black cherry (Prunus serotina), black gum (Nyssa sylvatica), black walnut (Juglans nigra), dogwood (Cornus spp.), Japanese snowbell (Styrax japonicus), maple (Acer spp.), oak (Quercus spp.), and paper birch (Betula papyrifera).

The adults and immatures of this species damage host plants by feeding on sap from stems, leaves, and the trunks of trees. In the springtime in Pennsylvania (late April - mid-May) nymphs (immatures) are found on smaller plants and vines and new growth of trees and shrubs. Third and fourth instar nymphs migrate to the tree of heaven and are observed feeding on trunks and branches. Trees may be found with sap weeping from the wounds caused by the insect’s feeding. The sugary secretions (excrement) created by this insect may coat the host plant, later leading to the growth of sooty mold. Insects such as wasps, hornets, bees, and ants may also be attracted to the sugary waste created by the lanternflies, or sap weeping from open wounds in the host plant. Host plants have been described as giving off a fermented odor when this insect is present.

Adults are present by the middle of July in Pennsylvania and begin laying eggs by late September and continue laying eggs through late November and even early December in that state. Adults may be found on the trunks of trees such as the tree of heaven or other host plants growing in close proximity to them. Egg masses of this insect are gray in color and look similar in some ways to gypsy moth egg masses.

Host plants, bricks, stone, lawn furniture, recreational vehicles, and other smooth surfaces can be inspected for egg masses. Egg masses laid on outdoor residential items such as those listed above may pose the greatest threat for spreading this insect via human aided movement.

For more information about the spotted lanternfly, visit this fact sheet: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/spotted-lanternfly .

Emerald Ash Borer: (Agrilus planipennis, EAB) in 2021 alone, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation has confirmed at least 28 new community detections of emerald ash borer in Massachusetts. To date, 11 out of the 14 counties in Massachusetts have confirmed emerald ash borer. (The remaining counties where EAB has yet to be detected are Barnstable, Dukes, and Nantucket counties.)A map of these locations and others previously known across the state may be found here: https://ag.umass.edu/fact-sheets/emerald-ash-borer .

Emerald Ash Borer: (Agrilus planipennis, EAB) in 2021 alone, the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation has confirmed at least 28 new community detections of emerald ash borer in Massachusetts. To date, 11 out of the 14 counties in Massachusetts have confirmed emerald ash borer. (The remaining counties where EAB has yet to be detected are Barnstable, Dukes, and Nantucket counties.)A map of these locations and others previously known across the state may be found here: https://ag.umass.edu/fact-sheets/emerald-ash-borer .

This wood-boring beetle readily attacks ash (Fraxinus spp.) including white, green, and black ash and has also been found developing in white fringe tree (Chionanthus virginicus) and has been reported in cultivated olive (Olea europaea). Signs of an EAB infested tree may include D-shaped exit holes in the bark (from adult emergence), “blonding” or lighter coloration of the ash bark from woodpecker feeding (chipping away of the bark as they search for larvae beneath), and serpentine galleries visible through splits in the bark, from larval feeding beneath. It is interesting to note that woodpeckers are capable of eating 30-95% of the emerald ash borer larvae found in a single tree (Murphy et al. 2018). Unfortunately, despite high predation rates, EAB populations continue to grow.

For further information about this insect, please visit: https://ag.umass.edu/fact-sheets/emerald-ash-borer . If you believe you have located EAB-infested ash trees, particularly in an area of Massachusetts not identified on the map provided, please report here: https://massnrc.org/pests/eabreport.htm .

Lymantria dispar: (Formerly Gypsy Moth; LD) Professionals working in parts of Berkshire County (ex. Alford, Great Barrington, Richmond, Sheffield, South Egremont, and Williamstown) as well as NY and CT report being deluged with questions from property owners looking to manage Lymantria dispar caterpillars in 2022 following expanding populations of this insect in those areas this season. Here is some information to help with those discussions:

Lymantria dispar: (Formerly Gypsy Moth; LD) Professionals working in parts of Berkshire County (ex. Alford, Great Barrington, Richmond, Sheffield, South Egremont, and Williamstown) as well as NY and CT report being deluged with questions from property owners looking to manage Lymantria dispar caterpillars in 2022 following expanding populations of this insect in those areas this season. Here is some information to help with those discussions:

In high populations of Lymantria dispar (formerly gypsy moth), scraping egg masses can be a futile effort. When populations are high, caterpillars can blow in from surrounding forested areas onto your property (next spring) even after an egg mass scraping effort is undertaken. Additionally, on large trees, female moths can lay their egg masses in areas that are not practical/safe to reach. However, if you do try to remove egg masses from high value specimen trees this fall and winter, be sure to scrape them into a can of soapy water. If scraped onto the ground, they may still hatch next spring.

A good plan would be to have an arborist come monitor the property and surrounding area this fall/winter once Lymantria dispar females are completely done laying eggs. (Additional egg mass survey information will also be available for Massachusetts through the Department of Conservation and Recreation once surveys are complete for 2021, here: ( https://www.mass.gov/guides/lymantria-dispar-gypsy-moth-in-massachusetts ). If there are large numbers of egg masses on your property and in the woods nearby, consider applying reduced risk insecticides next spring to protect high-value specimen trees from defoliation next year, especially if they could become hazardous if they were to decline. (Ex. trees near the home, garage, etc.) Applications would be made following 90-100 GDD's, after eggs have hatched, and caterpillars have settled to feed. Egg hatch begins roughly around the first week in May in MA, however this timing may depend upon spring temperatures. Special care should also be taken to protect trees that were defoliated this year, as two consecutive years of defoliation are often very stressful even for mature trees. Young trees/new plantings should be protected as well.

After caterpillars hatch, and once they settle to begin feeding (when they are approximately 3/4 inch in length or less), they are very susceptible to applications of the reduced risk insecticide known as Bacillus thuringiensis Kurstaki. This is a soil dwelling bacterium that is lethal to the caterpillars if they ingest it on the leaves. Another reduced risk option is the active ingredient spinosad (also derived from a soil dwelling bacterium). Spinosad should not be applied to plants in bloom, as it is toxic to pollinators - but that toxicity goes away once the product dries (in about 3 hours). Chlorantraniliprole is another reduced risk active ingredient that can be applied to the leaves of susceptible hosts when caterpillars are young and just beginning to feed.

The efficacy of systemic insecticides for the management of Lymantria dispar is not entirely understood. However, products containing azadirachtin, abamectin, or acephate are labelled for use against this insect. Of those, azadirachtin is a reduced risk insecticide. With regard to acephate, some research suggests that it is more effective at managing caterpillars feeding on smaller diameter trees than on larger trees (Dan Herms, Personal Communication).

LD moth has been in Massachusetts since the 1860's. This invasive insect from Europe often goes unnoticed, thanks to population regulation provided by the entomopathogenic fungus, E. maimaiga, as well as a NPV virus specific to LD moth caterpillars. (And to a lesser extent many other organisms, including other insects, small mammals, and birds who feed on LD moth.) However, if environmental conditions do not favor the life cycle of the fungus, outbreaks of LD moth caterpillars are possible. (Such as most recently from 2015-2018, with a peak in the LD moth population in 2017 in Massachusetts.)

Check out Episode 1 of InsectXaminer to reminisce about the 2015-2018 outbreak of this insect and learn more about the fungus and the virus and how to recognize caterpillars that have been killed by these pathogens: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/insectxaminer .

- Asian Longhorned Beetle: (Anoplophora glabripennis, ALB) Look for signs of an ALB infestation which include perfectly round exit holes (about the size of a dime), shallow oval or round scars in the bark where a female has chewed an egg site, or sawdust-like frass (excrement) on the ground nearby host trees or caught in between branches. Be advised that other, native insects may create perfectly round exit holes or sawdust-like frass, which can be confused with signs of ALB activity.

The regulated area for Asian longhorned beetle is 110 miles2 encompassing Worcester, Shrewsbury, Boylston, West Boylston, and parts of Holden and Auburn. If you believe you have seen damage caused by this insect, such as exit holes or egg sites, on susceptible host trees like maple, please call the Asian Longhorned Beetle Eradication Program office in Worcester, MA at 508-852-8090 or toll free at 1-866-702-9938.

To report an Asian longhorned beetle find online or compare it to common insect look-alikes, visit: http://massnrc.org/pests/albreport.aspx or https://www.aphis.usda.gov/pests-diseases/alb/report .

Jumping Worms: In recent years, public concern about Amynthas spp. earthworms, collectively referred to as “jumping or crazy or snake” worms, has dramatically increased. University researchers and Extension groups in many locations in the US are finding that these species cause not only forest ecosystem disturbances, but may also negatively impact soil structure and reduce plant growth in gardens and managed landscapes. They do this by voraciously devouring the organic layer of the soil while feeding very close to the soil surface, unlike other species of earthworms. In woodland areas, they can quickly eat all of the leaf litter on the forest floor. Jumping worms also leave a distinct grainy soil full of worm castings. The soil becomes granular and may look like dried coffee grounds.

Jumping Worms: In recent years, public concern about Amynthas spp. earthworms, collectively referred to as “jumping or crazy or snake” worms, has dramatically increased. University researchers and Extension groups in many locations in the US are finding that these species cause not only forest ecosystem disturbances, but may also negatively impact soil structure and reduce plant growth in gardens and managed landscapes. They do this by voraciously devouring the organic layer of the soil while feeding very close to the soil surface, unlike other species of earthworms. In woodland areas, they can quickly eat all of the leaf litter on the forest floor. Jumping worms also leave a distinct grainy soil full of worm castings. The soil becomes granular and may look like dried coffee grounds.

Unfortunately, there are currently no research-based management options available for these earthworms. So prevention is essential – preventing their introduction and spread into new areas is the best defense against them. Adult jumping worms can be 1.5 – 8 inches or more in length. Their clitellum (collar-like ring) is roughly located 1/3 down the length of the worm (from the head) and is smooth and cloudy-white and constricted. These worms may also wiggle or jump when disturbed, and can move across the ground in an S-shape like a snake. While the exact timing of their life cycle in MA might not be completely understood, their life cycle may be expected to go (roughly) something like this: they hatch in the late spring in 1-4 inches of soil, mature into adults during the summer and adults lay eggs sometime in August, and it is thought that their cocoons overwinter. (Adults perish with frost.) It is also worth noting here that jumping worms do not directly harm humans or pets.

For more information, listen to Dr. Olga Kostromytska’s presentation here: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/education-events/invasive-insect-webinars

*NEW*: UMass Extension Fact Sheets:

Earthworms in Massachusetts – History, Concerns, and Benefits: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/earthworms-in-massachusetts-history-concerns-benefits

Jumping/Crazy/Snake Worms – Amynthas spp.:

https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/jumpingcrazysnake-worms-amynthas-spp

Suggested reading includes Dr. Kostromytska’s recent “Hot Topics” article in Hort Notes (including an identification guide), here: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/newsletters/hort-notes/hort-notes-2021-vol-323

Additional resources can also be found here:

University of Minnesota Extension: https://extension.umn.edu/identify-invasive-species/jumping-worms

Cornell Cooperative Extension: http://ulster.cce.cornell.edu/environment/invasive-pests/jumping-worm

UNH Extension: https://extension.unh.edu/blog/invasive-spotlight-jumping-worms

Tree & Shrub Insects & Mites:

Bagworm: Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis is a native species of moth whose larvae construct bag-like coverings over themselves with host plant leaves and twigs. In certain areas across MA in 2020, increased populations of bagworms were observed and reported, particularly in urban forest settings and managed landscapes. More information can be found here: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/bagworm

Bagworm: Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis is a native species of moth whose larvae construct bag-like coverings over themselves with host plant leaves and twigs. In certain areas across MA in 2020, increased populations of bagworms were observed and reported, particularly in urban forest settings and managed landscapes. More information can be found here: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/bagworm

Bagworm caterpillars were reported defoliating honey locust in an urban forest setting in Northampton, MA on 7/27/2021. Caterpillars are quite large at this time, and feeding damage (defoliation of susceptible hosts) is apparent. These caterpillars develop into moths as adults. Their behaviors, life history, and appearance are interesting. The larvae (caterpillars) form “bags” or cases over themselves as they feed using assorted bits of plant foliage and debris tied together with silk. As the caterpillars feed and grow in size, so does their “bag”. Young, early instar caterpillars may feed with their bag oriented skyward, skeletonizing host plant leaves. As these caterpillars grow in size, they may dangle downward from their host plant, and if feeding on a deciduous host, they can consume the leaves down to the leaf veins. Pupation can occur in southern New England in late September or into October and this occurs within the “bag”. Typically, this means that the caterpillars could encounter a killing frost and die before mating could occur. However, in warmer areas of Massachusetts or if we experience a prolonged, warm autumn, it is possible for this insect to overwinter and again become a problem the following season. If the larvae survive to pupation, adult male moths emerge and are winged, able to fly to their flightless female mates. The adult male is blackish in color with transparent wings. The female is worm-like; she lacks eyes, wings, functional legs, or mouthparts. The female never gets the chance to leave the bag she constructs as a larva. The male finds her, mates, and the female moth develops eggs inside her abdomen. These eggs (500-1000) overwinter inside the deceased female, inside her bag, and can hatch roughly around mid-June in southern New England. Like other insects with flightless females, the young larvae can disperse by ballooning (spinning a silken thread and catching the wind to blow them onto a new host). While arborvitae and junipers can be some of the most commonly known host plants for this insect, the bagworm has a broad host range including both deciduous and coniferous hosts numbering over 120 different species. Bagworm has been observed on spruce, Canaan fir, honeylocust, oak, European hornbeam, rose, and London planetree among many others.