UMass Extension's Landscape Message is an educational newsletter intended to inform and guide Massachusetts Green Industry professionals in the management of our collective landscape. Detailed reports from scouts and Extension specialists on growing conditions, pest activity, and cultural practices for the management of woody ornamentals, trees, and turf are regular features. The following issue has been updated to provide timely management information and the latest regional news and environmental data.

Thanks for your continuing interest! To receive immediate notification when the next Landscape Message update is posted, be sure to join our e-mail list

To read individual sections of the message, click on the section headings below to expand the content:

Scouting Information by Region

Environmental Data

The following data was collected on or about June 21, 2023. Total accumulated growing degree days (GDD) represent the heating units above a 50ºF baseline temperature collected via regional NEWA stations (http://newa.cornell.edu) for the 2023 calendar year. This information is intended for use as a guide for monitoring the developmental stages of pests in your location and planning management strategies accordingly.

|

MA Region/Location |

2023 Growing Degree Days |

Soil Temp |

Precipitation |

Time/Date of Readings |

||

| Gain since last report |

2023 total |

Sun |

Shade |

|||

|

CAPE |

85 |

513 |

68 |

62 |

1.99 |

6/21/2023 12:00 PM |

|

SOUTHEAST |

92 |

511 |

70 |

62 |

2.15 |

6/21/2023 2:30 PM |

|

NORTH SHORE |

88 |

488 |

61 |

57 |

0.77 |

6/21/2023 10:00 PM |

|

EAST |

95 |

621 |

72 |

63 |

1.45 |

6/21/2023 4:00 PM |

|

METRO |

94 |

560 |

60 |

57 |

0.99 |

6/21/2023 6:00 AM |

|

CENTRAL |

98 |

613 |

62 |

60 |

1.67 |

6/21/23 3:00 PM |

|

PIONEER VALLEY |

111 |

642 |

70 |

64 |

0.88 |

6/21/2023 3:00 PM |

|

BERKSHIRES |

90 |

490 |

67 |

60 |

1.93 |

6/21/2023 6:00 PM |

|

AVERAGE |

94 |

555 |

66 |

61 |

1.48 |

- |

|

n/a = information not available |

||||||

US Drought Monitor: Most of eastern Barnstable County, the islands, a portion of southeastern Worcester county, and all of Berkshire county (approximately 20% of the total area of Massachusetts) are classified as "D0: Abnormally Dry" as of Thursday 6/22: https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/CurrentMap/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?MA

Phenology

| Indicator Plants - Stages of Flowering (BEGIN, BEGIN/FULL, FULL, FULL/END, END) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLANT NAME (Botanic / Common) | CAPE | S.E. | N.S. | EAST | METRO W. | CENT. | P.V. | BERK. |

|

Euonymus alatus (winged euonymus) |

* |

End |

End |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

Hydrangea macrophylla (bigleaf hydrangea) |

* |

Begin |

Begin |

Begin |

Begin |

Begin |

Begin/Full |

* |

|

Hydrangea arborescens (smooth hydrangea) |

Begin |

Full |

Begin |

Begin |

Begin |

Begin |

Begin/Full |

* |

|

Itea virginica (Virginia sweetspire) |

Begin/Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

* |

Full |

Full |

* |

|

Tilia cordata (littleleaf linden) |

Begin/Full |

End |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

* |

|

Rhus typhina (staghorn sumac) |

Begin |

Begin |

Begin |

Begin/Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

* |

|

Ligustrum spp. (privet) |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full/End |

* |

|

Catalpa speciosa (Northern catalpa) |

Begin/Full |

Full/end |

Full |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full |

|

Sambucus canadensis (American elderberry) |

Begin |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Full |

Begin/Full |

|

Kalmia latifolia (mountain laurel) |

Full/End |

Full/end |

Full/End |

Full/End |

Full/End |

End |

Full/End |

Full |

| * = no activity to report/information not available | ||||||||

Regional Notes

Cape Cod Region (Barnstable)

General Conditions:

The average temperature for the period from June 14 – June 21 was 63ºF with a high of 80ºF on June 16 and a low of 48ºF on June 20 & 21. The period started out warm, although the last 5 days have been cool with highs in the 60s and lows primarily in the 50s. Much needed precipitation fell on June 14 and June 17 from heavy showers, totaling nearly 2 inches. On June 14, light hail accompanied the showers in the upper Cape. The precipitation has helped alleviate a lack of soil moisture, at least temporarily.

Herbaceous plants seen in bloom include spiked speedwell (Veronica spicata), catmint (Nepeta spp.), baptisia (Baptisia australis), tickseed (Coreopsis spp), and early cultivars of daylily (Hemerocallis ‘Stella de Oro’). Woody plants seen in bloom include Japanese spiraea (Spiraea japonica), tree lilac (Syringa reticulata), Kousa dogwood (Cornus kousa), and ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius).

Pests/Problems:

Insect or insect damage observed during the period includes spongy moth caterpillars on oak, rose slug sawfly larvae on rose, cottony camellia scale on euonymus, aphids on many ornamentals, and earwig damage on herbaceous plants.

Disease symptoms or signs observed this period include beech leaf disease on American beech and European beech, apple scab on crabapple, sycamore anthracnose on sycamore, Venturia leaf and shoot blight on poplar, exobasidium gall on deciduous azalea and huckleberry, pear trellis rust on callery pear, guignardia leaf blotch on horsechestnut, leaf spot on river birch resulting in some light defoliation, and phytophthora root rot on smooth hydrangea. Red thread is active in turf.

Weeds in bloom include multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), black swallowwort (Cynanchum louiseae), cats ear (Hypochaeris radicata), black medic (Medicago lupulina), white clover (Trifolium repens), fleabane (Erigeron annuus), and narrowleaf plantain (Plantago lanceolata).

Lots of rabbits in some areas. Keep yourself protected from ticks.

Southeast Region (Dighton)

General Conditions:

The last week of spring for this year delivered 2.15 inches of rain. Most of the precipitation occurred on Sunday, June 18. The highest daytime temperatures were 74°F on Wednesday, June 14th, and the following Thursday. Temperatures trended cooler through the week with the morning low of 48°F on the morning of Wednesday, June 21st. The highest wind speed was 17 mph on the 14th.

Plants in flower: Catalpa speciosa (northern catalpa), Hydrangea arborescens (smooth hydrangea), H. macrophylla (bigleaf hydrangea), Itea virginica (Virginia sweetspire), Kalmia latifolia (mountain laurel), Ligustrum spp. (privet), Rhus typhina (staghorn sumac), Sambucus canadensis (American black elderberry).

Pests/Problems

Red thread on irrigated and commercially fertilized residential turf. Asiatic garden beetle adults have emerged and are mating preliminarily to egg laying. Ticks are still questing in high numbers. Emerald ash borer adults are present. Ash rust is causing defoliation on the few remaining trees that still have leaves.

North Shore (Beverly)

General Conditions:

Relatively cool temperatures persisted into this reporting period. Day temperatures were in the mid 60s most days except for June 15 and 16 when the daytime temperatures were in the high 70s. Night temperatures were in the low to high 50s. The average daily temperature for this period was 63℉ with the maximum temperature of 79℉ recorded on June 15 and the minimum temperature of 50℉ recorded on June 21. Woody plants seen in bloom include: tall stewartia (Stewartia monadelpha), Japanese tree lilac (Syringa reticulata), Peking tree lilac (Syringa pekinensis), Kousa dogwood (Cornus kousa), Virginia sweetspire (Itea virginica), Japanese hydrangea vine (Schizophragma hydrangeoides), American elderberry (Sambucus canadensis), mock orange (Philadelphus spp.) and mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia). Herbaceous plants in bloom include: white clematis (Clematis paniculata), Virginia rose (Rosa virginiana), garden roses (Rosa spp.), Baptisia (Baptisia australis), catmint (Nepeta spp.), goat’s beard (Aruncus dioicus), yellow corydalis (Corydalis lutea), ornamental onions (Allium spp.), water lily (Nymphaea spp.), oxeye daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare) and many annual plants.

Pests/Problems:

Powdery mildew of lilac (Microsphaera syringae) was observed on some lilac shrubs. Powdery mildew is favored by high relative humidity at night (which favors fungal spore formation) and warm daytime temperatures of 70-80℉. Apply an appropriate fungicide as soon as the first symptoms appear and repeat every 7-14 days if favorable conditions persist. Powdery mildew of Monarda (Erysiphe cichoracearum) continues to be observed on bee balm (Monarda), with severe powdery growth covering the leaves causing leaf drop. Rabbits are causing damage on some perennials such as phlox. Iron deficiency symptoms were observed on azalea, blueberry and some other plants. Iron deficiency occurs on acid loving plants when soil pH is above 6.2 and shows up as interveinal chlorosis (yellowing between veins). Iron deficiency can be corrected by applying acid fertilizers such as ammonium sulfate or applying elemental sulfur.

East (Boston)

General Conditions:

The summer solstice occurred on June 21. Conditions have continued to trend on the cool side for June. Daytime temperatures averaged 74ºF with a high of 83ºF on the 16th. Overnight lows averaged 57ºF. We received precipitation on three occasions totaling 1.45 inches; the majority, 1.2 inches falling on June 17th. We have reached 713 Growing Degree Days base 50. Plants in bloom include: Aruncus dioicus (goat’s beard), Rosa spp. (roses) and Syringa reticulata (Japanese tree lilac). Cornus kousa (Kousa dogwood) is having a prolific, extended bloom period.

Pests/Problems:

Perennial weeds in bloom include: black swallowwort (Cynanchum louiseae), curly dock (Rumex crispa), and bittersweet nightshade (Solanum dulcamara). Powdery mildew has been observed on Phlox paniculata (garden phlox).

Metro West (Acton)

General Conditions:

Welcome to the summer season! We are welcomed with a landscape full of color including, just to name a few, the white flowers of Catalpa speciosa (northern catalpa), Cornus kousa (Kousa dogwood), and Rhododendron viscosum (swamp azalea); the yellow flowers from Hemerocallis 'Stella D'Oro' (daylily) and Thermopsis caroliniana (southern lupine); the shades of red and pink from the many species and cultivars of Paeonia and Rosa; and lastly, the green from the grass and foliage. For the most part this past week, we’ve experienced pleasant yet wet days with moderate temperatures and cooler nights. Rain was recorded on 4 of the 7 days during this recording period, bringing our monthly total recorded precipitation to 3.18”. The historical monthly average rainfall for June is 3.93”. Hopefully there will be more precipitation to come over the remaining days of the month to close this gap and to meet our average. A high temperature of 81°F was recorded on both the 14th and 16th and a low temperature of 50°F was recorded on the 20th.

Pests/Problems:

Despite the sporadic rain events throughout the spring season, overall recorded precipitation is well below average levels. Many of our most invasive weeds have since flowered and are setting fruit and seed, including Alliaria petiolata (garlic mustard), Berberis thunbergii (barberry), Elaeagnus umbellata (autumn-olive), Lonicera maackii (Amur honeysuckle), and Rhamnus cathartica (common buckthorn).

Central Region (Boylston)

General Conditions:

Weather this week was average to cool given the time of year, with periods of rain, including some soaking rain on Saturday that resulted in nearly an inch of precipitation. Soils are adequately moist, minimizing the need for supplemental irrigation except for newly planted material. Overnight low temperatures are unseasonably cool, consistently in the 50’s all week. We are trending about average for rainfall for the month of June. There is much in bloom throughout the landscape, including perennials, and shrubs like Kousa dogwood (Cornus kousa) and its cultivars, which generally look great this season.

Pests/Problems:

Beech leaf disease is present and localized, having yet to spread throughout the region. Extensive damage was observed on American beech (Fagus grandifolia). Otherwise, in spite of the wet weather, remarkably little foliar disease is present at this time. Minor damage was observed on witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) and sugar maple (Acer saccharum).

Pioneer Valley (Amherst)

General Conditions:

This past reporting period was a continuation of the mild temperatures and lack of persistent sun that has dominated June in the Pioneer Valley. Following the hot start to the month, when temperatures were just above 90°F on 6/1 and 6/2, temperatures have mostly oscillated from the low 80s in the day to the low 50s at night. Full sun days have also been a rarity, occurring only a few times this month. Humidity is building at the time of writing and the extended forecast calls for a sustained period of showers and thunderstorms. Plants, however, seem to be doing well with the scattered showers, increase in humidity and patchy sun and clouds. Trees with indeterminate growth rates continue to produce new shoots and foliage (i.e. eastern hemlock, red maple and crabapple). Soil moisture is adequate in many locations, depending on localized accumulations from the scattered showers that have passed through the region. The most recent drought monitor shows “abnormally dry” conditions creeping into the western hill towns and eastern portions of the tri-counties. However, the brunt of the valley remains free of any drought classification. Supplemental watering is still required for recently transplanted trees and shrubs, but always keeping in mind not to overwater. Transplanting removes or injures a significant portion of a tree’s root system and until it recovers, it cannot take up water as it normally would. Weeds and the need for their removal is reaching its zenith as red maple seedlings, crab grass, nutsedge, bittersweet seedlings, and hairy bittercress, among many others are rapidly growing. Mountain laurels (Kalmia latifolia) have had an excellent bloom this year, which stands in stark contrast to many rhododendrons that were injured by the early February deep freeze.

Pests/Problems:

Powdery mildew is abundant on peony, beebalm, phlox, apple/crabapple and Japanese maple. Dogwood powdery mildew has been a problem in recent years and affected trees may have reddened, distorted foliage that appears to be wilting. Aphid leaf curling on elm and other scattered hardwoods is also very conspicuous. Recent observations along the Westfield River showed several towering American sycamores are totally devoid of foliage due to sycamore anthracnose. However, there were also scattered sycamores that were fully leafed out, showing the variation in susceptibility among individual trees. Weather conditions have been ideal for fungal pathogens to sporulate and spread. On smaller trees, when shoots and branches are killed by cankering fungi, they should be pruned immediately to limit disease spread. Scattered defoliation and feeding injury by insects has been observed on a wide array of trees and shrubs. In many cases, it’s very difficult to identify the causal agent and the injury is not significant. Many native insects feed gregariously on forest and landscape plants and their actions do not warrant active management.

Berkshire Region (West Stockbridge)

General Conditions:

After a sequence of unseasonable high temperatures followed by a sequence of unseasonable low temperatures through the early months, the recent weather during this scouting period has returned to normal for this time of year, i.e., the beginning of summer. Temperature data for the three NEWA sites in Berkshire County showed highs for the week occurring on June 20 with 80ºF in North Adams, and 78ºF in both Pittsfield and Richmond. Low temperatures all occurred just a day before, on June 19, with 50ºF in Pittsfield, 49ºF in North Adams, and 47ºF in Richmond. The mean temperatures for each site over the past week were: 64.2 for North Adams, 62.7 for Pittsfield, and 61.9 for Richmond. The other good news for the week was the ending of a stretch of very dry, near drought-like, conditions. Rainfall levels amounted to 1.93 inches here in West Stockbridge, 1.72 inches in North Adams, 1.64 inches in Pittsfield, and 1.60 inches in Richmond. Dry patches of turfgrass are now showing signs of recovery. Recently planted plants that had shown signs of drought stress have also recovered. Perennial borders are alive with floral displays. Among the dominant species are Digitalis spp. (foxgloves), Achillea spp. (yarrows), early Clematis, Alliums, and Nepeta (catmint).

Pests/Problems:

The one dominant factor that has affected the health and appearance of plants in the landscape was the now infamous hard freeze of May 18. Numerous species of plants, mostly woody species, are still showing browned foliage, naked branches (mostly in the upper portions of trees and shrubs, some twig dieback, and dead flower buds. This accounts for the failure of some of the plants listed on the Landscape Message phenology list to produce flowers. Spongy moth caterpillars are still present and range in size from just ¼ inch to a little over an inch in length. The numbers are not as great as in the past two years and other than holes in leaves, little or no defoliation has as yet occurred. The rains over the past week have prompted much slug and snail activity as witnessed by considerable chewing of leaves of annuals and herbaceous perennials. Other pests observed include: aphids on perennials and annuals, lily leaf beetle adults and larvae, imported willow leaf beetle pupae, 4-lined plant bugs, beech woolly aphid and apple wooly aphid, spruce spider mites, and spittlebugs. Diseases are few with the exception of cedar apple rust and apple scab on crabapples. One astonishing event is the considerable number of dead and dying white ash trees due to the emerald ash borer. As just one example, nearly every ash tree along Cross Road in West Stockbridge is now dead.

The one dominant factor that has affected the health and appearance of plants in the landscape was the now infamous hard freeze of May 18. Numerous species of plants, mostly woody species, are still showing browned foliage, naked branches (mostly in the upper portions of trees and shrubs, some twig dieback, and dead flower buds. This accounts for the failure of some of the plants listed on the Landscape Message phenology list to produce flowers. Spongy moth caterpillars are still present and range in size from just ¼ inch to a little over an inch in length. The numbers are not as great as in the past two years and other than holes in leaves, little or no defoliation has as yet occurred. The rains over the past week have prompted much slug and snail activity as witnessed by considerable chewing of leaves of annuals and herbaceous perennials. Other pests observed include: aphids on perennials and annuals, lily leaf beetle adults and larvae, imported willow leaf beetle pupae, 4-lined plant bugs, beech woolly aphid and apple wooly aphid, spruce spider mites, and spittlebugs. Diseases are few with the exception of cedar apple rust and apple scab on crabapples. One astonishing event is the considerable number of dead and dying white ash trees due to the emerald ash borer. As just one example, nearly every ash tree along Cross Road in West Stockbridge is now dead.

Regional Scouting Credits

- CAPE COD REGION - Russell Norton, Horticulture and Agriculture Educator with Cape Cod Cooperative Extension, reporting from Barnstable.

- SOUTHEAST REGION - Brian McMahon, Arborist, reporting from the Dighton area.

- NORTH SHORE REGION - Geoffrey Njue, Green Industry Specialist, UMass Extension, reporting from the Long Hill Reservation, Beverly.

- EAST REGION - Kit Ganshaw & Sue Pfeiffer, Horticulturists reporting from the Boston area.

- METRO WEST REGION – Julie Coop, Forester, Massachusetts Department of Conservation & Recreation, reporting from Acton.

- CENTRAL REGION - Mark Richardson, Director of Horticulture reporting from New England Botanic Garden at Tower Hill, Boylston.

- PIONEER VALLEY REGION - Nick Brazee, Plant Pathologist, UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab, reporting from Amherst.

- BERKSHIRE REGION - Ron Kujawski, Horticultural Consultant, reporting from Great Barrington.

Woody Ornamentals

Diseases

Recent pests, pathogens, or problems of interest seen in the UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab, a select few:

Beech leaf disease fact sheet: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/beech-leaf-disease

Fire blight, caused by Erwinia amylovora, on several commercial apple cultivars at the UMass Cold Spring Orchard. The trees started showing symptoms of fire blight in early to mid-June, which included blackened leaves and shoot tips, wilted shoots (Shepherd's crook) and dark discoloration of the fruit. Three submitted cultivars were all positive for the bacterium. In addition to the symptoms, bacterial ooze was also observed from the infected fruit (see photo). The bacterial ooze represents a sign of the pathogen that is often difficult to find. It is suspected this outbreak of fire blight was induced by the May 18 frost, an uncommon event in the northeast. More information on the possibility of frost-induced fire blight can be found here.

Fire blight, caused by Erwinia amylovora, on several commercial apple cultivars at the UMass Cold Spring Orchard. The trees started showing symptoms of fire blight in early to mid-June, which included blackened leaves and shoot tips, wilted shoots (Shepherd's crook) and dark discoloration of the fruit. Three submitted cultivars were all positive for the bacterium. In addition to the symptoms, bacterial ooze was also observed from the infected fruit (see photo). The bacterial ooze represents a sign of the pathogen that is often difficult to find. It is suspected this outbreak of fire blight was induced by the May 18 frost, an uncommon event in the northeast. More information on the possibility of frost-induced fire blight can be found here.

Venturia leaf and shoot blight of trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides) caused by Venturia moreletii. Several young trees planted in groups, approximately five- to seven-years-old, that experience full sun in good loam soils with drip irrigation. In the spring, V. moreletii attacks young and developing tissues, creating dark-colored stem and leaf lesions that rapidly develop. Infected leaves and stems wilt, shrivel and become dry and desiccated. The blackened blotches and lesions then develop an olive-green coating of asexual spores. These spores are dispersed by wind and splashing rainwater to nearby shoots and leaves, resulting in new infection centers. During ideal conditions (wet and mild), the pathogen can kill all terminal shoots in affected trees. Lateral shoots may be stunted but often become resistant, preventing a complete defoliation of the canopy.

Venturia leaf and shoot blight of trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides) caused by Venturia moreletii. Several young trees planted in groups, approximately five- to seven-years-old, that experience full sun in good loam soils with drip irrigation. In the spring, V. moreletii attacks young and developing tissues, creating dark-colored stem and leaf lesions that rapidly develop. Infected leaves and stems wilt, shrivel and become dry and desiccated. The blackened blotches and lesions then develop an olive-green coating of asexual spores. These spores are dispersed by wind and splashing rainwater to nearby shoots and leaves, resulting in new infection centers. During ideal conditions (wet and mild), the pathogen can kill all terminal shoots in affected trees. Lateral shoots may be stunted but often become resistant, preventing a complete defoliation of the canopy.

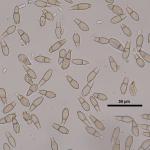

Branch dieback in the canopy of a Morton elm (Ulmus 'Morton' ACCOLADE) caused by the twig and branch cankering pathogen Phaeobotryon ulmicola. This pathogen has previously gone by Sphaeropsis and Botryodiplodia, but recent taxonomic study has placed the species in genus Phaeobotryon. The tree is eight-years-old and has been present at the site for three years. It resides in full sun on a turfed lawn and is well-watered. This spring, the tree appeared healthy except for one dead branch near the top of the canopy. Symptoms included sunken lesions, peeling and sloughing bark and a dark discoloration of the vascular tissue (see photo). Phaeobotryon can be an important pathogen on stressed and weakened elms, causing significant branch dieback. Healthy trees are often able to resist or contain infections. The tree had no symptoms of Dutch elm disease and this cultivar is known to be quite resistant to DED.

Branch dieback in the canopy of a Morton elm (Ulmus 'Morton' ACCOLADE) caused by the twig and branch cankering pathogen Phaeobotryon ulmicola. This pathogen has previously gone by Sphaeropsis and Botryodiplodia, but recent taxonomic study has placed the species in genus Phaeobotryon. The tree is eight-years-old and has been present at the site for three years. It resides in full sun on a turfed lawn and is well-watered. This spring, the tree appeared healthy except for one dead branch near the top of the canopy. Symptoms included sunken lesions, peeling and sloughing bark and a dark discoloration of the vascular tissue (see photo). Phaeobotryon can be an important pathogen on stressed and weakened elms, causing significant branch dieback. Healthy trees are often able to resist or contain infections. The tree had no symptoms of Dutch elm disease and this cultivar is known to be quite resistant to DED.

Report by Nick Brazee, Plant Pathologist, UMass Extension Plant Diagnostic Lab, UMass Amherst.

Insects and Other Arthropods

Citizen Science Opportunity: Reporting Native Ground Nesting Bees

The Cornell College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability and the Ground Nesting Bees Community Science Project are asking for your help collecting data on native bee populations and nesting sites. Your contributions will help scientists better understand the importance of native bees and how to protect them in our local environments.

What to Look For: Safely monitor ground nesting bees from early spring to late summer. Entrances in grass and soil are indicators of bee activity. Upload a photo of a bee entering or exiting its nest to iNaturalist (GNbee). To learn more, visit: https://www.gnbee.org/ and upload your photos here.

Some notes on safety: take appropriate precautions if you are allergic to bee stings. While many ground nesting bees or wasps do not sting, it is not a guarantee that you will not encounter a stinging species if participating.

Current Nuisance Problems of Note:

- Deer Tick/Blacklegged Tick: Ixodes scapularis adults are active all winter and spring, as they typically are from October through May, and “quest” or search for hosts at any point when daytime temperatures are above freezing. Engorged females survive the winter and lay 1,500+ eggs in the forest leaf litter beginning around Memorial Day (late May). For images of all deer tick life stages, along with an outline of the diseases they carry, visit: https://www.capecod.gov/departments/cooperative-extension/programs/ticks-bugs/ or https://web.uri.edu/tickencounter/species/blacklegged-tick/.

Anyone working in the yard and garden should be aware that there is the potential to encounter deer ticks. The deer tick or blacklegged tick can transmit Lyme disease, human babesiosis, human anaplasmosis, and other diseases. Preventative activities, such as daily tick checks, wearing appropriate clothing, and permethrin treatments for clothing (according to label instructions) can aid in reducing the risk that a tick will become attached to your body. If a tick cannot attach and feed, it will not transmit disease. For more information about personal protective measures, visit: https://www.capecod.gov/departments/cooperative-extension/programs/ticks-bugs/.

The Center for Agriculture, Food, and the Environment provides a list of potential tick identification and testing resources.

*In the news: UMass Amherst has now been designated as the location for the New England Center of Excellence in Vector-Borne Diseases (NEWVEC). This CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) funded center will work to reduce the risk of vector-borne diseases spread by ticks, mosquitoes, and other blood-sucking insects or insect relatives in New England. For more information and to contact NEWVEC, visit: https://www.newvec.org/. To contact the center for more information about their Spring 2023 Project ITCH (“Is Tick Control Helping”), visit: https://www.newvec.org/itch .

Note: Dog ticks (Dermacentor variabilis) continue to be noticeably active in parts of Berkshire and Hampshire County in 2023. They are present in large numbers this year even in environments where tick activity is typically low, such as in mowed lawns.

- Mosquitoes: According to the Massachusetts Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Science and the Department of Public Health, there are at least 51 different species of mosquito found in Massachusetts. Mosquitoes belong to the Order Diptera (true flies) and the Family Culicidae (mosquitoes). As such, they undergo complete metamorphosis, and possess four major life stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Adult mosquitoes are the only stage that flies and many female mosquitoes only live for 2 weeks (although the life cycle and timing will depend upon the species). Only female mosquitoes bite to take a blood meal, and this is so they can make eggs. Mosquitoes need water to lay their eggs in, so they are often found in wet or damp locations and around plants. Different species prefer different habitats. It is possible to be bitten by a mosquito at any time of the day, and again timing depends upon the species. Many are particularly active from just before dusk, through the night, and until dawn. Mosquito bites are not only itchy and annoying, but they can be associated with greater health risks. Certain mosquitoes vector pathogens that cause diseases such as West Nile virus (WNV) and eastern equine encephalitis (EEE).

Click here for more information about mosquitoes in Massachusetts.

EEE and WNV testing and tracking for this season began on June 12, 2023. The Massachusetts Department of Public Health tracks animal cases, human cases, and mosquito positive samples from traps from June through October in Massachusetts. No cases or positive samples have been reported as of June 20, 2023. Click here for more information.

There are ways to protect yourself against mosquitoes, including wearing long-sleeved shirts and long pants, keeping mosquitoes outside by using tight-fitting window and door screens, and using insect repellents as directed. Products containing the active ingredients DEET, permethrin, IR3535, picaridin, and oil of lemon eucalyptus provide protection against mosquitoes. Be aware that not all of these can be safely used on young children. Read and follow all label instructions for safety and proper use.

Click here for more information about mosquito repellents.

- Wasps/Hornets: Many wasps are predators of other arthropods, including pest insects such as certain caterpillars that feed on trees and shrubs. Adult wasps hunt prey and bring it back to their nest where young are being reared, as food for the immature wasps. A common such example are the paper wasps (Polistes spp.) who rear their young on chewed up insects. They may be seen searching plants for caterpillars and other soft-bodied larvae to feed their young. Paper wasps can sting, and will defend their nests, which are open-celled paper nests that are not covered with a papery “envelope”. These open-celled nests may be seen hanging from eaves or other outdoor building structures. Aerial yellow jackets and hornets create large aerial nests that are covered with a papery shell or “envelope”. Common yellow jacket species include those in the genus Vespula. Dolichovespula maculata is commonly known as the baldfaced hornet, although it is not a true hornet. The European hornet (Vespa crabro) is three times the size of a yellow jacket and may be confused for the northern* giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia). The European hornet is known to Massachusetts, but the northern giant hornet is not. If you are concerned that you have found or photographed a northern giant hornet, please report it here: https://massnrc.org/pests/report.aspx. Paper wasps and aerial yellowjackets overwinter as fertilized females (queens) and a single female produces a new nest annually in the late spring. Queens start new nests, lay eggs, and rear new wasps to assist in colony/nest development.Nests are abandoned at the end of the season. Some people are allergic to stinging insects, so care should be taken around wasp/hornet nests. Unlike the European honeybee (Apis mellifera), wasps and hornets do not have barbed stingers, and therefore can sting repeatedly when defending their nests. It is best to avoid them, and if that cannot be done and assistance is needed to remove them, consult a professional.

*Read more about the common name change for Vespa mandarinia.

Woody ornamental insect and non-insect arthropod pests to consider, a selected few:

Highlighted Invasive Insects & Other Organisms Update:

Spongy Moth: Lymantria dispar egg hatch was reported on April 18, 2023, in Great Barrington, MA (Berkshire County) and on 5/2/2023 in Erving, MA and Millers Falls, MA (Franklin County).

Spongy Moth: Lymantria dispar egg hatch was reported on April 18, 2023, in Great Barrington, MA (Berkshire County) and on 5/2/2023 in Erving, MA and Millers Falls, MA (Franklin County).

Spongy moth caterpillars have been observed molting and passing through different instars as they develop in Berkshire County, MA.

The expectation is that parts of western MA may experience noticeable defoliation by this insect again in 2023. By the end of June and the beginning of July, most of this feeding will have occurred and we will be able to tell whether or not defoliation has again been significant. Additionally, by that time, whether or not the population is hit by an epizootic of the spongy moth caterpillar killing fungus (Entomophaga maimaiga) will be noticeably detectable as well.

For more information about spongy moth, view the first episode of InsectXaminer.

Why did the common name for Lymantria dispar change recently? Read more here.

Spotted Lanternfly: (Lycorma delicatula, SLF) is a non-native, invasive insect that feeds on over 103 species of plants, including many trees and shrubs that are important in our landscapes. It overwinters as an egg mass, which the adult female insect lays on just about any flat surface. Pictures of egg masses can be seen here.

Spotted Lanternfly: (Lycorma delicatula, SLF) is a non-native, invasive insect that feeds on over 103 species of plants, including many trees and shrubs that are important in our landscapes. It overwinters as an egg mass, which the adult female insect lays on just about any flat surface. Pictures of egg masses can be seen here.

Updates about spotted lanternfly egg hatch in Massachusetts are now available from MDAR at https://massnrc.org/pests/blog/?p=3205.

SLF egg hatch has now occurred at all four locations in Massachusetts where this insect has become established. Eggs seem to have hatched earliest in Springfield, MA and at that location, MDAR reports seeing both first and second instar nymphs active at this time (as of 6/21/2023).

Currently, the only established populations of spotted lanternfly in Massachusetts are in Fitchburg, Shrewsbury, Worcester, and Springfield MA. Therefore, there is no reason to be preemptively treating for this insect in other areas of Massachusetts. If you suspect you have found spotted lanternfly in additional locations, please report it immediately to MDAR here. If you are living and working in the Fitchburg, Shrewsbury, Worcester, and Springfield, MA areas, please be vigilant and continue to report anything suspicious.

For More Information:

From UMass Extension:

*New*: Spotted Lanternfly Management Guide for Professionals

*Note that management may only be necessary in areas where this insect has become established in Massachusetts, and if high value host plants are at risk. Preemptive management of the spotted lanternfly is not recommended.

Check out the InsectXaminer Episode about spotted lanternfly adults and egg masses!

From the MA Department of Agricultural Resources (MDAR):

Spotted Lanternfly Fact Sheet and Map of Locations in MA

Spotted Lanternfly Management Guide for Homeowners in Infested Areas

*New*: Spotted Lanternfly Look-alikes in MA

*New*: Spotted Lanternfly Egg Mass Look-alikes

- Asian Longhorned Beetle: (Anoplophora glabripennis, ALB) Look for signs of an ALB infestation which include perfectly round exit holes (about the size of a dime), shallow oval or round scars in the bark where a female has chewed an egg site, or sawdust-like frass (excrement) on the ground nearby host trees or caught in between branches. Be advised that other, native insects may create perfectly round exit holes or sawdust-like frass, which can be confused with signs of ALB activity.

Adult Asian longhorned beetles typically begin to emerge from trees by July 1st in Massachusetts. By that time and throughout the rest of the summer, it is important to take photographs of and report any suspicious longhorned beetles to the Asian Longhorned Beetle Eradication Program phone numbers listed below.

The regulated area for Asian longhorned beetle is 110 square miles encompassing Worcester, Shrewsbury, Boylston, West Boylston, and parts of Holden and Auburn. If you believe you have seen damage caused by this insect, such as exit holes or egg sites, on susceptible host trees like maple, please call the Asian Lonbghorned Beetle Eradication Program office in Worcester, MA at 508-852-8090 or toll free at 1-866-702-9938.

Report an Asian longhorned beetle find online or compare it to common insect look-alikes here.

- White Spotted Pine Sawyer (WSPS): Monochamus scutellatus adults can emerge in late May throughout July, depending on local temperatures. This is a native insect in Massachusetts and is usually not a pest. Larvae develop in weakened or recently dead conifers, particularly eastern white pine (Pinus strobus). However, the white spotted pine sawyer looks very similar to the invasive Asian Longhorned Beetle, Anoplophora glabripennis, ALB. ALB adults do not emerge in Massachusetts until July and August. Beginning in July, look for the key difference between WSPS and ALB adults, which is a white spot in the top center of the wing covers (the scutellum) on the back of the beetle. White spotted pine sawyer will have this white spot, whereas Asian longhorned beetle will not. Both insects can have other white spots on the rest of their wing covers; however, the difference in the color of the scutellum is a key characteristic. See the Asian longhorned beetle entry above for more information about that non-native insect.

Emerald Ash Borer: (Agrilus planipennis, EAB) has been detected in at least 11 out of the 14 counties in Massachusetts. A map of these locations across the state may be found at https://ag.umass.edu/fact-sheets/emerald-ash-borer . Additional information about this insect is provided by the MA Department of Conservation and Recreation at https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/b60f63199fa14805a8b9f7c82447a25b.

Emerald Ash Borer: (Agrilus planipennis, EAB) has been detected in at least 11 out of the 14 counties in Massachusetts. A map of these locations across the state may be found at https://ag.umass.edu/fact-sheets/emerald-ash-borer . Additional information about this insect is provided by the MA Department of Conservation and Recreation at https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/b60f63199fa14805a8b9f7c82447a25b.

This wood-boring beetle readily attacks ash (Fraxinus spp.) including white, green, and black ash and has also been found developing in white fringe tree (Chionanthus virginicus) and has been reported in cultivated olive (Olea europaea). Signs of an EAB infested tree may include D-shaped exit holes in the bark (from adult emergence), “blonding” or lighter coloration of the ash bark from woodpecker feeding (chipping away of the bark as they search for larvae beneath), and serpentine galleries visible through splits in the bark, from larval feeding beneath. It is interesting to note that woodpeckers are capable of eating 30-95% of the emerald ash borer larvae found in a single tree (Murphy et al. 2018). Unfortunately, despite high predation rates, EAB populations continue to grow. However, there is hope that biological control efforts will eventually catch up with the emerald ash borer population and preserve some of our native ash tree species for the future.

- Jumping Worms: Amynthas spp. earthworms, collectively referred to as “jumping or crazy or snake” worms, overwinter as eggs in tiny, mustard-seed sized cocoons found in the soil or other substrate (ex. compost). Immature jumping worms hatch from their eggs by approximately mid-to-late May. It may be impossible to see them at first, and it may be more likely that jumping worms are noticed when the first adults begin to appear at the end of May and in June. It is easy to misidentify jumping worms (ex. mistake European earthworms for jumping worms) if only juveniles are found. In August and September, most jumping worms have matured into the adult life stage and identification of infestations is more likely to occur at that time of year.

For More Information, see these UMass Extension Fact Sheets:

Earthworms in Massachusetts – History, Concerns, and Benefits

Jumping/Crazy/Snake Worms – Amynthas spp.

A Summary of the Information Shared at UMass Extension’s Jumping Worm Conference in January 2022

Invasive Jumping Worm Frequently Asked Questions (Over 70 Questions and their Answers)

Tree & Shrub Insect Pests (Native and Invasive):

- Andromeda Lace Bug: Stephanitis takeyai is most commonly encountered on Japanese Andromeda. Eggs are tiny and inserted into the midveins on the lower surface of the leaf and covered with a coating that hardens into a protective covering. 5 nymphal stages are reported. Nymphs are different in appearance from the adults, often covered with spiky protrusions. 3-4 generations per year have been observed in New England, with most activity seen between late-May into September (starting at approximately 120 GDD’s, Base 50°F). Both nymphs and adults can be seen feeding on leaf undersides. Adults have delicate, lace-like wings and what appears to be an "inflated hood" that covers their head. Adults are approximately 1/8 of an inch long. Arrived in the US in Connecticut in 1945 from Japan (Johnson and Lyon, 1991).

Can cause severe injury to Japanese andromeda, especially those in full sun. Mountain Andromeda (Pieris floribunda) is highly resistant to this pest. Like other lace bugs, this insect uses piercing-sucking mouthparts to drain plant fluids from the undersides of the leaves. Damage may be first noticed on the upper leaf surface, causing stippling and chlorosis (yellow or off-white coloration). Lace bug damage is distinguished from that of other insects upon inspecting the lower leaf surface for black, shiny spots, "shed" skins from the insects, and adult and nymphal lace bugs themselves.

A first sign of potential lace bug infestation is stippling or yellow/white colored spots or chlorosis on host plant leaf surfaces. Lace bugs excrete a shiny, black, tar-like excrement that can often be found on the undersides of infested host plant leaves. Flip leaves over to inspect for this when lace bug damage is suspected.

Mountain Andromeda (Pieris floribunda) is considered to be highly resistant to this insect and can be used as an alternative for such plantings, along with other lace bug-resistant cultivars. Consider replacing Japanese Andromeda with mountain andromeda as a way to manage for this pest. Natural enemies are usually predators, and sometimes not present in large enough numbers in landscapes to reduce lace bug populations. Structurally and (plant) species complex landscapes have been shown to reduce azalea lace bug (Stephanitis pyrioides) populations through the increase of natural enemies.

- Arborvitae Leafminer: In New England and eastern Canada, four species of leafminers are known to infest arborvitae. These include Argyresthia thuiella, A. freyella, A. aureoargentella, and Coleotechnites thujaella. The arborvitae leafminer, A. thuiella, is the most abundant of these and has the greatest known range when compared to the others. (It is also found in the Mid-Atlantic States and as far west as Missouri). Moths of this species appear from mid-June to mid-July and lay their eggs. The damage caused by all of these species is nearly identical. Trees, however, have been reported to lose up to 80% of their foliage due to arborvitae leafminer and still survive. At least 27 species of parasites have been reported as natural enemies of arborvitae leafminers, the most significant of which may be a parasitic wasp (Pentacnemus bucculatricis). Arborvitae leafminer damage causes the tips of shoots and foliage to turn yellow and brown. If infestations are light, prune out infested tips.

- Azalea Lace Bug: Stephanitis pyrioides is native to Japan. The azalea lace bug deposits tiny eggs on the midveins on leaf undersides. They then cover the area where the egg was inserted with a brownish material that hardens into a protective covering. Each female may lay up to 300 eggs (University of Florida). Nymphs hatch from the eggs and pass through 5 instars. The length of time this takes depends on temperature. Between 2 and 4 generations may be completed in a single year. In Maryland, there are four generations per year. Adults are approximately 1/10 of an inch in length with lacy, cream colored, transparent wings held flat against the back of the insect. Wings also have black/brown patches. Adults of this species also possess a "hood" over their head. Nymphs are colorless upon hatch from the egg, but develop a black color as they mature and are covered in spiny protrusions.

Immatures and adults use piercing-sucking mouthparts to remove plant fluids from leaf tissues. This feeding leaves behind white-yellow stippling on the upper surface of host plant leaves, even though the insects themselves feed on the underside of the leaf. Plants in full sun are often particularly damaged by these insects. In heavy infestations, plants in full sun may be killed by the feeding of the azalea lace bug.

Begin scouting for azalea lace bugs when 120 GDD’s (Base 50°F) are reached. This species is active throughout the summer, following. Look for dark, black tar-like spots of excrement deposited by immature and adult lace bugs on the underside of susceptible host plant leaves, especially on leaves with white-yellow stippling visible on the upper surface. If lace bugs are not already known to the location, check susceptible hosts located in full sun first. Monitor plants for lace bug feeding from late April through the summer.

Plant azaleas in partial shade. Resistance has been reported in Rhododendron atlanticum, R. arborescens, R. canescens, R. periclymenoides, and R. prunifolium.

Many of the natural enemies reported for this insect are predators. They are rarely abundant enough to reduce damaging populations of lace bugs, especially on plants in sunny locations. Structurally and (plant) species complex landscapes have been shown to reduce azalea lace bug (Stephanitis pyrioides) populations through the increase of natural enemies.

- Azalea Sawflies: There are a few species of sawflies that impact azaleas. Johnson and Lyon's Insects that Feed on Trees and Shrubs mentions three of them. Amauronematus azaleae was first reported in New Hampshire in 1895 and is likely found in most of New England. Adults of this species are black with some white markings and wasp-like. Generally green larvae feed mostly on mollis hybrid azaleas. Remember, sawfly caterpillars have at least enough abdominal prolegs to spell “sawfly” (so 6 or more prolegs). Adults are present in May, and females lay their eggs and then larvae hatch and feed through the end of June. There is one generation per year. Nematus lipovskyi has been reared from swamp azalea (Rhododendron viscosum). Adults of that species have been collected in April (in states to the south) and May (in New England) and larval feeding is predominantly in late April and May in Virginia and June in New England. One generation of this species occurs per year, and most mollis hybrid azaleas can be impacted. A third species, Arge clavicornis, is found as an adult in July and lays its eggs in leaf edges in rows. Larvae are present in August and September. Remember, Bacillus thuringiensis Kurstaki does not manage sawflies.

Bagworm: Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis is a native species of moth whose larvae construct bag-like coverings over themselves with host plant leaves and twigs. This insect overwinters in the egg stage, within the bags of deceased females from last season. Eggs may hatch and young larvae are observed feeding around mid-June, or roughly between 600-900 GDD’s. Newly hatched and feeding bagworm caterpillars are small and less likely to be noticed. By late July and August, these caterpillars will be large and their feeding noticeable on individual trees and shrubs.

Bagworm: Thyridopteryx ephemeraeformis is a native species of moth whose larvae construct bag-like coverings over themselves with host plant leaves and twigs. This insect overwinters in the egg stage, within the bags of deceased females from last season. Eggs may hatch and young larvae are observed feeding around mid-June, or roughly between 600-900 GDD’s. Newly hatched and feeding bagworm caterpillars are small and less likely to be noticed. By late July and August, these caterpillars will be large and their feeding noticeable on individual trees and shrubs.- Black Vine Weevil: Otiorhynchus sulcatus adults are 0.35-0.51 inches in length and are therefore slightly larger than some of the other destructive species of Otiorhynchus. Adults are also black in color, all are female, and they cannot fly. This insect is native to Europe and is now found in the northern half of the United States and Canada. Adults will drop from foliage to the ground when disturbed and are easily hidden due to their camouflaged coloration. Adults require a few weeks of feeding before each female will lay up to 500 eggs in the soil near the base of the plant around the end of June, early-July. These eggs will hatch and larvae will burrow into the soil to feed on the roots of the plant. Larvae are white approx. 1/2 an inch in length with brown heads, legless, and C-shaped. This weevil usually overwinters as a partially developed larvae, but occasionally adults will seek shelter, such as homes, in which to overwinter. Larvae do a lot of destructive feeding in late-May, early- June just prior to pupation. Pupae are milky-white with visible appendages. One generation per year occurs in the Northeast. Many additional weevil species are pests of ornamental plants. Tiny, hemispherical notches in leaf margins are a sign of adult feeding, usually on lower branches. However, other weevils will cause this type of damage on rhododendron; it can only be used diagnostically on yew, as no other insects currently cause that type of damage on that host. The major damage is caused by larvae feeding on the rootlets. This can be a very serious pest.

Activity of the black vine weevil can be monitored using the following growing degree day ranges: 148-400 GDD's (overwintering adults; Source: Cornell Cooperative Extension) 1100–1665 GDD's (adults; Source: Robert Childs, UMass Extension), Base 50°F, March 1st Start Date. Monitor adults with crumpled burlap around plant base, as the adults hide in dark places during the day and are active at night. Pitfall traps around the base of infested plants may also be used. Look for notched leaves on host plants, particularly yew, starting in June. Larvae may be found on the roots of wilting host plants with notched leaves. Scouting is highly necessary in areas where this insect is an issue.

Some physical barriers to the adults (on the stem/base of the plant) have been suggested, since adults cannot fly and must crawl up the plant. Success varies. Knocking adults off the plant and onto a white surface, such as a sheet, so they are visible and can be collected and killed may be very time consuming (and must be done at night, when the adults are active). Some adults may be missed. Cleaning up beds and leaf litter/dropped branches can help remove favorable overwintering sites for the adults. Some rhododendrons are resistant to foliar damage.

Birds may be good predators of this insect. Beneficial nematode drenches are available for the larvae, and are most effective in containerized plants. Apply when larvae are present and when temperatures are favorable to the species of nematode being used. Follow instructions carefully as the nematodes are living organisms and proper treatment can increase efficacy (such as watering before/after nematode application).

- Boxwood Leafminer: Monarthropalpus flavus partly grown fly larvae overwinter in the leaves of susceptible boxwood. Yellowish mines may be noticeable on the undersides of leaves. This insect grows rapidly in the spring, transforming into an orange-colored pupa. After pupation, adults will emerge and white colored pupal cases may hang down from the underside of leaves where adults have emerged. Adults may be observed swarming hosts between 300-650 GDD’s, or roughly the end of May through June. Most cultivars of Buxus sempervirens and B. microphylla are thought to be susceptible. Resistant cultivars such as ‘Vardar Valley’ and ‘Handsworthiensis’ are good choices at sites where this insect has been a problem.

- Cottony Taxus Scale: Pulvinaria floccifera, also referred to as the cottony camellia scale, utilizes such hosts as taxus, camellia, holly, hydrangea, Japanese maple, euonymus, magnolia, and jasmine, among others. Females have laid the long, narrow, white and fluted egg sac that makes them much more noticeable. Eggs will hatch over an extended period of 6 weeks and crawlers may be treated between 802-1388 GDD’s. This insect can cause the host to appear off-color. They also produce honeydew which promotes sooty mold growth. Dieback is not common with this insect. Target the underside of the foliage. Horticultural oil, neem oil, and insecticidal soaps may be used to manage these soft scales. Reduced risk options help preserve natural enemies.

- Boxwood Psyllid: Psylla buxi feeding can cause cupping of susceptible boxwood leaves. Leaf symptoms/damage may remain on plants for up to two years. English boxwood may be less severely impacted by this pest. Eggs overwinter, buried in budscales, and hatch around budbreak of boxwood. Eggs may hatch around 80 GDD’s. While foliar applications may be made between 290-440 GDD’s, the damage caused by this insect is mostly aesthetic. Therefore, typically, management is not necessary.

- Dogwood Borer: Synanthedon scitula is a species of clearwing moth whose larvae bore not only into dogwood (Cornus), but hosts also include flowering cherry, chestnut, apple, mountain ash, hickory, pecan, willow, birch, bayberry, oak, hazel, myrtle, and others. Kousa dogwood appear to be resistant to this species. Signs include the sloughing of loose bark, brown frass, particularly near bark cracks and wounds, dead branches, and adventitious growth. The timing of adult emergence can be expected when dogwood flower petals are dropping and weigela begins to bloom. Adult moth flights continue from then until September. Emergence in some hosts (ex. apple) appears to be delayed, but this differs depending upon the location in this insect’s range. Eggs are laid singly, or in small groups, on smooth and rough bark. Female moths preferentially lay eggs near wounded bark. After hatch, larvae wander until they find a suitable entrance point into the bark. This includes wounds, scars, or branch crotches. This insect may also be found in twig galls caused by other insects or fungi. Larvae feed on phloem and cambium. Fully grown larvae are white with a light brown head and approx. ½ inch long. Pheromone traps and lures are useful for determining the timing of adult moth emergence and subsequent management.

- Dogwood Sawfly: Macremphytus tarsatus has one generation per year. The larvae of the dogwood sawfly overwinter in decaying wood and occasionally compromised structural timber. An overwintering "cell" is created in this soft wood. Pupation occurs in the springtime and adults can take a lengthy time to emerge, roughly between late May and July. 100+ eggs are laid in groups on the underside of leaves. Eggs hatch and the larvae feed gregariously, initially skeletonizing leaves. As the caterpillars grow in size, they are capable of eating the entire leaf with the exception of the midvein. Larval appearance varies greatly throughout instars, so much so that one might mistake them for multiple species. Early instars are translucent and yellow, but as the caterpillars grow they develop black spots (over yellow) and become covered in a white powder-like material. Larvae and their shed skins may resemble bird droppings. Full grown larvae begin to wander in search of a suitable overwintering location. Rotting wood lying on the ground is preferred for this.

Foliage of dogwood, especially gray dogwood (Cornus racemosa) may be impacted. Skeletonizes leaves at first, then eats all but the midvein.

- Elm Leaf Beetle: Xanthogaleruca (formerly Pyrrhalta) luteola is found on American elm (Ulmus americana; not preferred), Chinese Elm (Ulmus parvifolia; not preferred), English Elm (Ulmus procera; preferred host), Japanese Zelkova (Zelkova serrata), and Siberian Elm (Ulmus pumila; preferred host).

This species was accidentally introduced into the eastern United States early in the 1800's. Since then, it has been found throughout the USA anywhere elms are located. It also occurs in eastern Canada. The adult elm leaf beetle overwinters in protected areas, such as the loose bark of trees, but can also be a nuisance when it tries to invade homes in search of overwintering protection. Beetles will try to enter houses or sheds in the fall.

In the spring, the adult beetles will fly back to the host plant and chew small, semi-circular holes in the leaves. The adult female can lay 600-800 yellow eggs in her life. Eggs are laid in clusters on the leaves and resemble pointy footballs. Larvae are tiny, black, and grub-like when they hatch from the egg. Young larvae will skeletonize the undersides of leaves. As they grow in size, the larvae become yellow-green with rows of black projections. Oldest larvae may appear to have two black stripes along their sides, made from the black projections. There are 3 larval instars. Mature larvae will wander down the trunk of the host tree and pupate in the open on the ground at the tree base or in cracks and crevices in the trunk or larger limbs. They spend approximately 10 or so days as a pupa, and then the adults emerge. Those adults will fly to the foliage of the same host plant or other adjacent potential hosts in the area, where they will lay eggs. In the fall, the adults will leave the host plant in search of overwintering shelter. In most locations in the USA, two generations of this insect are possible per year. In warmer locations, 3-4 generations per year are possible.

Leaves are skeletonized by the larvae. Skeletonization may cause the leaf to turn brown or whitish. Adults are capable of chewing through the leaf, often in a shothole pattern. When in very large populations, they are capable of completely defoliating plants. Populations of this insect can fluctuate from year to year, and often management is not necessary if populations are low. However, defoliation for consecutive seasons may lead to branch dieback or death of the entire tree.

- Euonymus Scale: Unaspis euonymi is an armored scale that can be found on euonymus, holly, bittersweet, and pachysandra. This insect can cause yellow spotting on leaves, dieback, and distorted bark. For crawlers, early June timing is suggested between 533-820 GDD’s for management. (Eggs begin to hatch in early June.)

- Fall Webworm: Hyphantria cunea is native to North America and Mexico. It is now considered a world-wide pest, as it has spread throughout much of Europe and Asia. (For example, it was introduced accidentally into Hungary from North America in the 1940’s.) Hosts include nearly all shade, fruit, and ornamental trees except conifers. In the USA, at least 88 species of trees are hosts for these insects, while in Europe at least 230 species are impacted. In the past history of this pest, it was once thought that the fall webworm was a two-species complex. It is now thought that H. cunea has two color morphs – one black headed and one red headed. These two color forms differ not only in the coloration of the caterpillars and the adults, but also in their behaviors. Caterpillars may go through at least 11 molts, each stage occurring within a silken web they produce over the host. When alarmed, all caterpillars in the group will move in unison in jerking motions that may be a mechanism for self-defense. Depending upon the location and climate, 1-4 generations of fall webworm can occur per year. Fall webworm adult moths lay eggs on the underside of the leaves of host plants in the spring. These eggs hatch in late June or early July depending on climate. Young larvae feed together in groups on the undersides of leaves, first skeletonizing the leaf and then enveloping other leaves and eventually entire branches within their webs. Webs are typically found on the terminal ends of branches. All caterpillar activity occurs within this tent, which becomes filled with leaf fragments, cast skins, and frass. Fully grown larvae then wander from the webs and pupate in protected areas such as the leaf litter where they will remain for the winter. Adult fall webworm moths emerge the following spring/early summer to start the cycle over again. 50+ species of parasites and 36+ species of predators are known to attack fall webworm in North America. Fall webworms typically do not cause extensive damage to their hosts. Nests may be an aesthetic issue for some. If in reach, small fall webworm webs may be pruned out of trees and shrubs and destroyed. Do not set fire to H. cunea webs when they are still attached to the host plant.

- Hemlock Looper: Two species of geometrid moths in the genus Lambdina are native insects capable of defoliating eastern hemlock, balsam fir, and white spruce. Adult moths lay their eggs on the trunk and limbs of hosts in September and October, and eggs will hatch by late May or early June. (L. fiscellaria caterpillars may be active between 448-707 GDD’s.) Monitor susceptible hosts for small, inch-worm like caterpillars. Where populations are low, no management is necessary. Hemlock loopers have several effective natural enemies.

- Hibiscus Sawfly: The larvae of the hibiscus (mallow) sawfly, likely Atomacera decepta, may be observed feeding on hibiscus hosts at this time. Sawfly larvae develop into wasp-like adults (Order: Hymenoptera) and therefore these “caterpillars” will not be managed by Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki which is specific to the Lepidoptera (caterpillars that develop into moths or butterflies as adults). Reduced risk active ingredients such as spinosad are labelled for use against sawfly larvae. However, given that hibiscus are very attractive to pollinators, non-chemical management options such as hand picking and disposing of larvae, when possible, are best. Spinosad is toxic to pollinators until it dries. Click here for more information about the risks of insecticide active ingredients to pollinators.

The hibiscus (mallow) sawfly adult female uses her ovipositor to cut slits into leaf surfaces to deposit her eggs. Larvae emerge from these eggs and begin by first feeding on leaf undersides when small, and then move to feed on leaf surfaces as they grow in size. Only large leaf veins may be left behind if the population is large enough. Larvae have been observed moving to the base of the plant to pupate. Adults emerge and in some locations in the US, multiple generations have been recorded per year. This insect is known in the mid-Atlantic and Midwest states, but was reported feeding on Hibiscus spp. in Connecticut in 2004 and 2005 and has previously been reported in Massachusetts. The timing of the life cycle of this insect, as well as how many generations occur per year in Massachusetts, however, is not fully understood. Some research has shown that Hibiscus acetosella, H. aculeatus, and H. grandiflora seem to either exhibit some resistance to or tolerance of hibiscus sawfly feeding. In one study, all three had few if any eggs or larvae and were given the lowest damage rating among the species evaluated. This insect also does not feed on rose of Sharon or H. rosasinensis. It has, however, been reported to “voraciously” feed on H. moscheutos, H. palustris, H. militaris, and H. lasiocarpus.

Imported Willow Leaf Beetle: Plagiodera versicolora adult beetles overwinter near susceptible hosts. Adult beetles will chew holes and notches in the leaves of willow once they become available. Females lay yellow eggs in clusters on the undersides of leaves. Larvae are slug-like and bluish-green in color. They will feed in clusters and skeletonize the leaves. Most plants can tolerate the feeding from this insect, and foliage will appear brown. Repeated yearly feeding can be an issue, in which case management of the young larvae may be necessary. Take care with treatment in areas near water.

Imported Willow Leaf Beetle: Plagiodera versicolora adult beetles overwinter near susceptible hosts. Adult beetles will chew holes and notches in the leaves of willow once they become available. Females lay yellow eggs in clusters on the undersides of leaves. Larvae are slug-like and bluish-green in color. They will feed in clusters and skeletonize the leaves. Most plants can tolerate the feeding from this insect, and foliage will appear brown. Repeated yearly feeding can be an issue, in which case management of the young larvae may be necessary. Take care with treatment in areas near water.

Check out Episode 4 of InsectXaminer to see the imported willow leaf beetle in action.

Lily Leaf Beetle: Lilioceris lilii adults overwinter in sheltered places. As soon as susceptible hosts such as Lilium spp. (Turk’s cap, tiger, Easter, Asiatic, and Oriental lilies) and Fritillaria spp. break through the ground, the adult lily leaf beetles are known to feed on the new foliage. (Note: daylilies are not hosts.) Adult lily leaf beetles were observed to be active in Hanson, MA on 4/14/2023. Typically, in May, mating will occur and each female will begin to lay 250-450 eggs in neat rows on the underside of the foliage. If there are only a few plants in the garden, hand picking and destroying overwintering adults can help reduce local garden-level populations at that time.

Lily Leaf Beetle: Lilioceris lilii adults overwinter in sheltered places. As soon as susceptible hosts such as Lilium spp. (Turk’s cap, tiger, Easter, Asiatic, and Oriental lilies) and Fritillaria spp. break through the ground, the adult lily leaf beetles are known to feed on the new foliage. (Note: daylilies are not hosts.) Adult lily leaf beetles were observed to be active in Hanson, MA on 4/14/2023. Typically, in May, mating will occur and each female will begin to lay 250-450 eggs in neat rows on the underside of the foliage. If there are only a few plants in the garden, hand picking and destroying overwintering adults can help reduce local garden-level populations at that time.

Check out Episode 3 of InsectXaminer to see the lily leaf beetle in action.

- Spruce Bud Scale: Physokermes piceae is a pest of Alberta and Norway spruce, among others. Immatures overwinter on the undersides of spruce needles, dormant until late March. By April, females may move to twigs to complete the rest of their development. Mature scales are reddish brown, globular, 3 mm. in diameter, and found in clusters of 3-8 at the base of new twig growth. They closely resemble buds and are often overlooked. Crawlers are present around June.

- Spruce Spider Mite: Oligonychus ununguis is a cool-season mite that becomes active in the spring from tiny eggs that have overwintered on host plants. Hosts include spruce, arborvitae, juniper, hemlock, pine, Douglas-fir, and occasionally other conifers. This particular species becomes active in the spring and can feed, develop, and reproduce through roughly June. When hot, dry summer conditions begin, this spider mite will enter a summer-time dormant period (aestivation) until cooler temperatures return in the fall. This particular mite may prefer older needles to newer ones for food. Magnification is required to view spruce spider mite eggs. Tapping host plant branches over white paper may be a useful tool when scouting for spider mite presence. (View with a hand lens.) Spider mite damage may appear on host plant needles as yellow stippling and occasionally fine silk webbing is visible.

Viburnum Leaf Beetle: Pyrrhalta viburni is a beetle in the family Chrysomelidae that is native to Europe, but was found in Massachusetts in 2004. By 2008, viburnum leaf beetle was considered to be present throughout all of Massachusetts. Larvae are present and feeding on plants from approximately late April to early May until they pupate sometime in June. Much damage from viburnum leaf beetle feeding is currently apparent in areas of Massachusetts where this insect has become established. See photo courtesy of Tom Ingersoll from 6/5/2023. Adult beetles emerge from pupation by approximately mid-July and will also feed on host plant leaves, mate, and lay eggs at the ends of host plant twigs where they will overwinter. This beetle feeds exclusively on many different species of viburnum, which includes, but is not limited to, susceptible plants such as V. dentatum, V. nudum, V. opulus, V. propinquum, and V. rafinesquianum. Some viburnum have been observed to have varying levels of resistance to this insect, including but not limited to V. bodnantense, V. carlesii, V. davidii, V. plicatum, V. rhytidophyllum, V. setigerum, and V. sieboldii. More information about viburnum leaf beetle may be found at http://www.hort.cornell.edu/vlb/ and at https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/viburnum-leaf-beetle.

Viburnum Leaf Beetle: Pyrrhalta viburni is a beetle in the family Chrysomelidae that is native to Europe, but was found in Massachusetts in 2004. By 2008, viburnum leaf beetle was considered to be present throughout all of Massachusetts. Larvae are present and feeding on plants from approximately late April to early May until they pupate sometime in June. Much damage from viburnum leaf beetle feeding is currently apparent in areas of Massachusetts where this insect has become established. See photo courtesy of Tom Ingersoll from 6/5/2023. Adult beetles emerge from pupation by approximately mid-July and will also feed on host plant leaves, mate, and lay eggs at the ends of host plant twigs where they will overwinter. This beetle feeds exclusively on many different species of viburnum, which includes, but is not limited to, susceptible plants such as V. dentatum, V. nudum, V. opulus, V. propinquum, and V. rafinesquianum. Some viburnum have been observed to have varying levels of resistance to this insect, including but not limited to V. bodnantense, V. carlesii, V. davidii, V. plicatum, V. rhytidophyllum, V. setigerum, and V. sieboldii. More information about viburnum leaf beetle may be found at http://www.hort.cornell.edu/vlb/ and at https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/viburnum-leaf-beetle.- Yellow Poplar Weevil: Odontopus calceatus is also known as the sassafras weevil, the magnolia leafminer, or the tulip tree leafminer. This insect, as all of these common names suggest, feeds on yellow poplar (tulip tree; Liriodendron tulipifera), sassafras (Sassafras albidum), magnolia (Magnolia spp.), as well as bay laurel (Laurus nobilis). This insect is native to much of the eastern United States. Both the larvae and the adults of the yellow poplar weevil will feed on its hosts. Adults feed on the leaves and buds while the larvae mine the leaves. Adult feeding causes irregular holes to form in the leaves. Yellow poplar weevils overwinter as adults in sheltered areas, such as the leaf litter, around their hosts. In the early spring, they initiate feeding on the buds and newly opening leaves of the host plant. By May, they lay eggs in the midrib of the leaves on leaf undersides. Eggs will hatch and the larvae mine the leaves, creating blotch-like mines. This mining begins at the tip (point) of the leaf on tulip tree and Magnolia grandiflora hosts. Yellow poplar weevil larvae are white, legless, and approximately 2 mm long. Up to 9 larvae have been recorded in a single blotch mine. Larvae are mostly observed in late May and June. Pupation occurs in the leaf mines and adults of the new generation emerge to feed on leaves. Adults have been observed feeding as late as August in the southern portions of its range in the US (ex. Mississippi). Adult weevils may seek indoor shelters (such as homes) for overwintering protection. Feeding damage from this insect is not often reported as of economic importance, however in the southern parts of its range outbreaks have occasionally occurred (Johnson and Lyon, 1991). Natural enemies of the yellow poplar weevil have been reported, particularly hymenopteran parasitoids. Five species (Heterolaccus hunteri, Habrocytus piercei, Horismenus fraternus, Zagrammosoma multilineatum, and Scambus hispae) have been reported to kill 50% of yellow poplar weevil pupae (Burns and Gibson, 1968).

Concerned that you may have found an invasive insect or suspicious damage caused by one? Need to report a pest sighting? If so, please visit the Massachusetts Introduced Pests Outreach Project.

Reported by Tawny Simisky, Extension Entomologist, UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, & Urban Forestry Program

Landscape Weeds

For identification of weed species noted below, refer to UMass Extension's Weed Herbarium: https://ag.umass.edu/weedid

Do not delay, treat garlic mustard, Alliaria petiolata, now. Second year plants are past flowering and seed pods are visible. In most locations, the seedpods are still green meaning the seed is not yet mature. Garlic mustard is a biennial and herbicide applications at this time of year will control second-year plants before they go to seed as well as the first-year seedlings.

Do not attempt to control Japanese knotweed at this time, as herbicide applications are not effective when applied in the early part of the growing season. Cutting or mowing of new growth and previous year stems in the spring is a great way to prepare for an herbicide application during the later part of the season. Whether cutting or mowing was done this spring or not, now is the time to allow knotweed to grow. Timing and and herbicide product selection and application timing will be provided when the application window for effective control arrives later in the season.

Inspect areas of the landscape where new trees or shrubs, especially those that were field grown, have been planted in the last year. Look for perennial weeds that may be growing from the root ball. Canada thistle, mugwort, quackgrass, bindweed and horsenettle are some of the possible culprits. Perennial weeds can be spot treated with glyphosate-based products.

In the last week, yellow nutsedge has become very apparent in landscape beds. Now is the time to treat yellow nutsedge. The best product options are the translocated, non-selective herbicides such as glyphosate, applied as a directed spray or wick application. In turf settings, halosufuron can be applied. Applications should be completed by the third week in June.

Several reports of winter injury to ornamental bamboo have been received. Unlike Japanese knotweed, which is a broadleaf plant, bamboo is a grass. The suspected cause of this winter injury is a relatively mild last week of January followed by low temperatures well below zero on the first weekend in February. Overnight low temperatures in some locations in central and western Massachusetts reached 15 to 25 below zero. Leaves of bamboo turned yellow and brown with occasional stem death. The rhizomes and crowns do not seem to be impacted and bamboo has sent up new shoots.

Reported by Randy Prostak, Weed Specialist, UMass Extension Landscape, Nursery, & Urban Forestry Program

Additional Resources

Pesticide License Exams - The MA Dept. of Agricultural Resources (MDAR) is now holding exams online. For more information and how to register, go to: https://www.mass.gov/pesticide-examination-and-licensing.

To receive immediate notification when the next Landscape Message update is posted, join our e-mail list or follow us on Facebook.

For a complete listing of landscape, nursery, and urban forestry program upcoming events, see our calendar at https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/upcoming-events.

For commercial growers of greenhouse crops and flowers - Check out UMass Extension's Greenhouse Update website.

For professional turf managers - Check out our Turf Management Updates.